Magda Campos-Pons: Enshrining Afro-Caribbean Womanhood

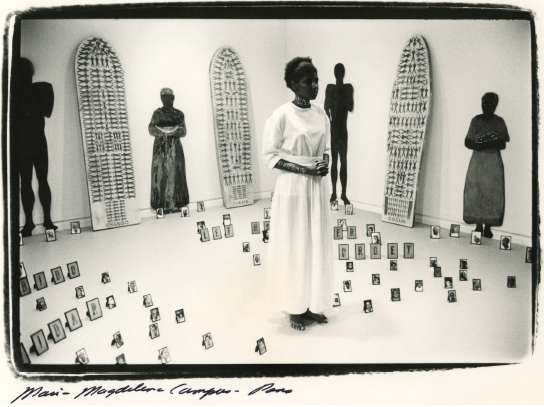

“Behold” is the title given to Cuban artist María Magdalena Campos-Pons’ exhibition recently opened at the Brooklyn Museum, under the exquisite curatorial vision of Carmen Hermo. The show is a major celebration of transnational and transgenerational Black women’s survival. I cannot think of a more pertinent title, as it almost magically coincides with Magda’s performative invitation: behold what a Black Cuban woman has decided that she is; while, at the same time, she beholds the public, through her Black, female, Caribbean, Cuban gaze.

I have always identified Magda’s works as shrines to Afro-Caribbean womanhood, in which she consistently recreates what I call the self-birth of the Black woman, the enactment of our self-invention, the discovery and free exercise of our own sense of humanity. Through a very prolific career spanning over forty years, Magda has been opening paths we can embark on in our endeavor to think and reinvent ourselves, constantly asking and answering herself the unavoidable question: What is to be a Black Cuban woman in the diaspora? This, considering all our diasporas: the forced transatlantic transplantation of our ancestors along with other displacements. From her birthplace, La Vega, an old sugar plantation in the province of Matanzas, a place impregnated with the dehumanization of enslaved African bodies, to the Cuban capital, Havana, where she completed her studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte; then to multiples cities in the United States, from Boston, where the artist taught at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts for 25 years to Nashville, where she currently holds the Cornelius Vanderbilt Endowed Chair of Fine Arts at Vanderbilt University. With all these migrations ingrained in her Black body, Magda makes us ponder whether there would exist an invisible continuity between the so-called African Diaspora and an unquenched thirst for home, which is a constant preoccupation of Black people in the Americas.

As descendants of African men and women sequestered and obliged to consider home the very place in which they were dispossessed of their humanity, do we carry uprooting and displacements fatally inscribed in our DNA? The question has been central to the work of so many Black writers and artists: Toni Morrison asked in The Source of Self-Regard, “How do we decide where we belong?;” an interrogation echoed by Saidiya Hartman, when she wrote, in Lose Your Mother, “What place in the world could sate four hundred years of yearning for a home?;” the same that tormented James Baldwin, who after so much wandering across the world in search of a place to call home, ended up acknowledging that “the place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it.”

And it is precisely to the center of this intimate, uncharted territory where Magda leads us: taking us back to our bodies and our flesh, where all our truths reside, where we are always someone else than the Other, that cumulus of identities foisted upon us through centuries of Euro-patriarchal epistemological hegemony. In Magda’s works, there is just that, the Black Cuban Female Body in the world, immersed in her own universe. But, most importantly, seen by herself in the universe that only she authored, with the help of her ancestors and orishas, of course.

Entering the exhibition is abandoning ourselves to the uncanny, a world at once familiar and unknown, terrifying, and enchanting. To this profusion of newness, our only guide is our senses, which follows the path traced by the gaze of a Black Caribbean woman. In most works, this gaze is hidden, covered, apparently idle behind closed eyes, or even non-existent, as the artist usually confronts us with her naked back, like in The Right Protection.

Who is that woman? How can we know who she is if she does not talk to us, if she does not offer us her face? Everything she gives us is her back. Yet, we know, we sense that she incisively observes us. And this is where precisely her right protection is: the unintelligibility of her body, that body that no one can apprehend, classify, or understand, but through which she keeps gazing at us, studying us, through a sea of eyes painted on her Black back.

From one piece to the other, the sea, the waters, the orisha Yemaya—the goddess of the oceans—and all forms of motherhood in the Afro-Cuban religion known as Santería, are omnipresent in María Magdalena Campos-Pons’ art. Reviewing Magda’s work means being washed again and again by waves of irresistible, violent blue colors. Waters are so fundamental for us islanders, Cubans, Caribbeans, and descendants of enslaved people throughout the Americas. Works like Of the Two Waters, Spoken Softly with Mama, and The Seven Powers Come by the Sea remind us that our entire history of pain and survival is contained in the waters that carry and bring us in our unrelenting errantry. With these works, we remember that the waters cleanse us, stripping us of versions of ourselves that obscure who we truly are, rather than define us. In pieces like these, we feel the survival of our ancestors within ourselves, in our own bodies: millions of enslaved Africans were massacred as human beings forced to cross the Atlantic Ocean, whereas we, their descendants, find rebirth through our ancestral memory, kept in the oceans by the orisha Yemaya.

In the installation Spoken Softly with Mama, which welcomes the public in “Behold,” delicate crystal irons disposed on the floor seem like islands or boats. We don’t know what exactly they are: “repeated” islands whose people do not find another option but to survive or abandon them, or an allusion to the precarious boats used to cross the waters in search of a better future, or just a future, some future, any future. There, on the floor, the little irons recreate our infinite disseminations. They also form an archipelago of memories that we cannot always recover, because our Black memories are consistently absent from historical archives and canonic literary production. But these memories remain alive in our bodies, and those irons disposed as little vessels on the floor constitute symbols of our journeys and the journeys of our ancestors.

All that we are at the present is in constant conversation with our mothers, whose portraits are displayed by Magda on the iron boards––also reminiscent of the Middle Passage’s slave ships––surrounding the piece. We can feel it. Among us circulate all these family stories woven into our everyday lives: through our labor, our joy, our games, our dances, our quietness, our dreams, and our stories, crossing the artificial borders of time and space. These are the untold, systemically invisibilized, but enduring connections that Magda recreates in her work. Many times, she does so by using Yoruba liturgic objects and the colors of our orishas, for example, red and black for Eleggua (also known as Eshu in other Afro-diasporic cosmological systems, the trickster orisha that opens, twists, and rectifies human paths) who is represented in the triptych Red Composition, from the series “Los caminos” (The Path).

Santería liturgic necklaces function as unbreakable links between the mother and the daughter. Thus, in Replenishing, the ancestral power quietly flows, enabling our survival through generations. Here, the necklaces––Eleggua’s red and black, but also blue, white, and yellow alluding to Yemaya and Oshun, goddesses of the oceans and the rivers in Cuban Santería––become an umbilical cord, keeping the two women together as much as separating them; forging an image of the tortuous, knotted, but permanent, intergenerational continuity between Black women.

This is also portrayed in Umbilical Cord, where a cord connects different female wombs, generators of life, serving as a thread linking feminine stories in Magda’s own family. Again, the red and black colors refer to Elegguá, the unpredictable orisha that at the same time guarantees a hidden togetherness in universal harmony. In all these works, there is no permanence, but instead transcendence. This transcendence, brought by a powerful matrilineal energy, allows the artist to tend bridges between her different realities and histories, between Africa, Cuba, and the United States.

But, again, who is this woman?

Answers might arise from a piece that I do not tire of discussing, through its multiple versions, When I Am Not Here / Estoy Allá.

Who is the Black woman with an impassable face and the naked torso painted white, asserting that, “Patria is a trap” and that “identity could be a tragedy”?

Her body––what she really is––appears covered by white substances, perhaps alluding to European enlightenment, or the whiteness of the hegemonic Europatriarcal epistemology? In this triptych, her Black skin is only shown in the second polaroid, where her face is surrounded by sticks known in Cuba as ‘garabatos.’ A liturgic attribute of Eleggua, the garabato––a work tool used in Cuba to clear the weeds––is his instrument to create new paths into the wilderness. Garabatos might also have been priceless tools for our maroon ancestors, when they escaped the plantation and created their paths through the forest, self-emancipating and inventing new lives outside of bondage. Thus, Eleggua and his garabatos convey in these pieces a clear message of liberation and the possibility of laboring in the creation of new forms of identification that are more adequate than the social ones.

Who is this person? Are the words Black, Cuban, woman enough to identify her? Or is she someone else: a human being only invented and defined by herself?

Campos-Pons’ interpretation of identity is puzzling: it appears in her works as a tragic issue but there is also an urgent reference to the infinite movements of the body and of culture, affecting us between here and there (allá). And then, where exactly is here and where is there? Incessant travels across history, national boundaries, races, cultures, languages, and ideologies are exposed on Magda’s body, powerfully resonating with Stuart Hall’s words as he discussed the concept of identification: “There is always ‘too much’ or ‘too little’—an over-determination or a lack, but never a proper fit, a totality.” None of the identities that supposedly label us succeed in apprehending who we truly are. Ultimately, what remains is only the body, here and allá, aquí and there: the black flesh of a Cuban, intensely diasporic woman.

—

*María Magdalena Campos-Pons: Behold is on display at the Brooklyn Museum from Sept. 15, 2023–Jan. 14, 2024. For more information, click here.

Odette Casamayor-Cisneros is associate professor of Latin American & Caribbean Cultural Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and the Inaugural Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Presidential Fellow at the University of Miami's Cuban Heritage Collection. Centered on the Afro-Latin American and Afro-Latinx experiences, Professor Casamayor’s current work examines self-identification processes and the production of counter-hegemonic knowledge in the global African Diaspora. Previous publications include the 2013 book Utopia, dystopia e ingravidez: reconfiguraciones cosmológicas en la narrativa postsoviética cubana and the collection of stories Una casa en los Catskills in 2016. Her numerous award-winning academic, journalistic, and literary works are featured in renowned publications, such as Small Axe, Transition, Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, Cuban Studies, Bulletin of Latin American Review, and Cahiers d'études africaines. Casamayor-Cisneros earned a Ph.D. in Arts and Literature at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), in Paris, and holds a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Havana. Fellowships and grants from, among others, Harvard University, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the UNESCO have supported her research.