‘Dominicanidades’ in Motion, with artist Raelis Vasquez

Raelis Vasquez is an artist of movement. In his portraiture paintings, we travel through the senses, accepting a subtle invitation to imagine and feel subjects that refuse physical or temporal constraint. In Homeowners (2022), we witness the swift zoom and recklessness of an adolescent's bike ride, and in Muchacha en Agua (2022), the trickling cloudiness you experience in your ears when swimming across calm water currents. Momentous, yet monotonous acts interface in Matrimonio (2020), including sounds of pen-on-paper handwriting competing with the soft ruffling of sweltering palm trees. The brisk chill of winter air palpable in Sentir (2019) may be the muse of the decisive stare that is a signature of Vasquez’s work––a temporally-based aesthetic of cool only the most confidently audacious seek to replicate, and emotions that sing of diaspora, homeland, and the mixed excitement for a new life. Agua Agua (2022) illustrates this careful attention to coolness and dignity in the midst of struggle through the quotidian transport of distilled water jugs on a dust-flinging motorbike, while wearing the latest denim style, the resurrected fanny pack, and an impeccably lined haircut.

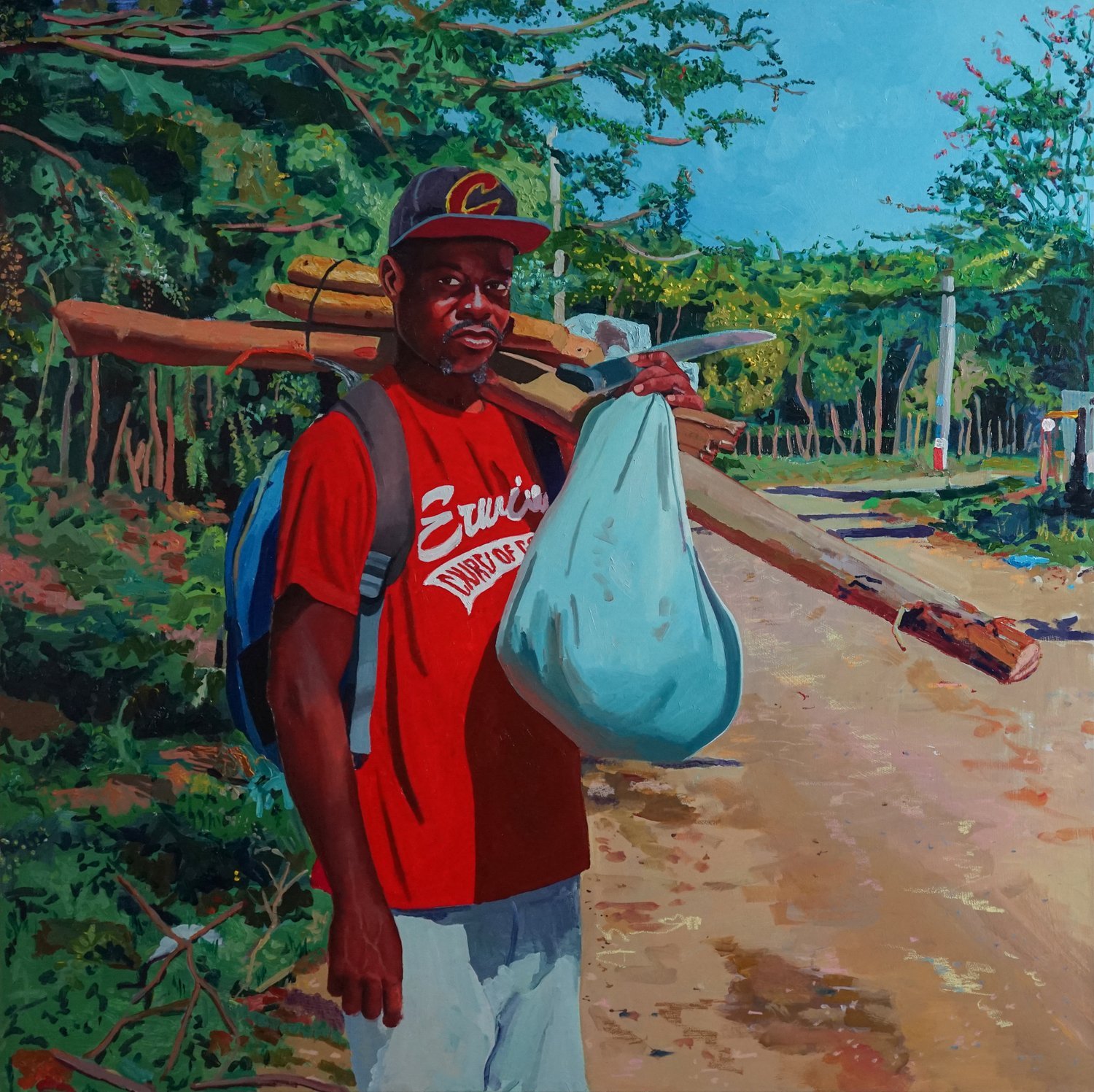

Adaptation and beauty require motion. To adapt to new conditions and contexts is to transform perspectives on the place one left and the place one is arriving to. Change is as existential as it is geographic, an arduous process without an end point. We return and revisit, sometimes physically, but always in memories summoned by familiar sights and experiences, reminding us of evolution and its continual necessity. To produce beauty, as we all hope our lives to be in abundance of, is to move and work towards its manifestations. This is the imperative of life. Vasquez makes this conspicuous through the deeply intimate moments of migrants and countryside communities, relishing in a solemn dinner feast at the end of a long work day, as in Buen Provecho (2020), or being immersed in blossoming foliage while carrying heavy wood and a machete, as in Tierra y Cielo (2021).

Vasquez’s genre of portraiture also fosters contemplation on the role and presence of people on this shared planet, where we employ discursive strategies that separate “us” from “nature,” or the cities and societies we have created for ourselves and what was here before our presence. In these times where there is much conversation on human impact and exploitation of nature, Vasquez provides us a bold expression of integration and communion across his works, while also nudging us to examine our continual manipulation of nature as an emblem of success, as we see in Homeowners (2022). Vasquez also designs a world where humans and nature are seemingly co-constitutive focal points, positioning them in a way where either could be the background to the foreground. These are Indigenous and African epistemologies and ontologies at work, where Vasquez (re)constructs an existence that embraces fluidity, plurality, a symbiotic relationship between people and nature; as well as temporal revisiting.

Almost exclusively choosing to paint a single national group, particularly one that faces discrimination in many contexts, confronts the painter with difficult choices on which symbols, actions, and gestures to adopt. What differentiates and identifies these people, as “a people?” How can we recast an individual experience as “collective?” On what does this sit at the base of? And how is that reflected back to the viewer? What is the visual language of honesty and truth? There are a plethora of problematic tropes intolerant of difference or the marginalized that could be drawn from as a way to aggrandize regressive nationalist ideas. Instead, Vasquez’s subjects and themes display particular and specific aspects of Dominican-ness that are Black, African and Indigenous descended; migratory, rural, working, and middle-class; and connected to Haiti—all of whom are working through the ingredients of daily life, with dignity and determination. These Dominicans are busy being themselves, and living so vibrantly that one only has a few seconds to take their snapshot. Time passes too quickly. The people in Vasquez’s paintings, and the nature that envelops them, will not just sit for you.

Raelis Vasquez is himself in constant motion. Over the past decade, Vasquez has exhibited in dozens of group and solo exhibitions in New York, Berlin, London, and Chicago, a few years shy of a BFA at The Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA at Columbia University. The following conversation between us provides glimpses into his life story, artistic inspirations, intentions, and future projects. My hope is that you continue to explore Vasquez’s work and that of other contemporary Caribbean and Dominican artists whose art insists on sensations, movement, and the complex notions of (national) self(hood).

—

XLB: I know Chicago to be a place where intense debates and visions about identity and politics percolate into vibrant mainstream, underground, and ethno-racial neighborhood art scenes. What about Chicago motivated a questioning of your identity, compared to growing up in New Jersey? In what ways has Chicago impacted and influenced your work?

RV: I always think of Chicago as the place where I went from being a painter and someone who was very interested in the principles and elements of design, to being an artist and being in conversation with myself about my own story. Being in Chicago gave me distance away from my previous context, which was New Jersey (East Coast) and the Dominican Republic (DR). Chicago is where I started to think about my experiences as an immigrant from DR and everything that came along with it in a more introspective way. It spurred the development of the work I am creating now.

XLB: Why painting? Did you or do you currently work with other artistic mediums? How did the experience of migration influence you as an artist?

RV: Primarily, I focus on painting, and drawing is also an important aspect of my work. I create 2D works on canvas and paper and I enjoy working with ceramics. I'm excited to bring ceramics into my practice in the future.

There is something that’s mesmerizing about paint, color, and its history. A lot of it stems from my early experiences with drawing and looking at paintings as a young boy. It's something that had always felt bigger than me and that history felt a bit intimidating. I never saw myself reflected in the works and I was hyper aware of how important these paintings are in society. I felt the need to understand the material. It captivated my ambition. I wanted to be a part of telling these kinds of stories, but in my own way.

For me, painting is always a challenge and a place of discovery. When I immigrated to the States, my family and I had to rediscover our identity and our place in this new world. I think I am still responding to that.

XLB: What insights or lessons about Dominicans in Quisqueya and in the diaspora do you hope are gained by the viewers of your work?

RV: My work investigates certain histories, personal relationships, individuals, and communities in the Dominican Republic. I am aiming to give dignity, celebrate, and critique different aspects of my story and culture.

I explore many tensions in Quisqueya. I am thinking about the inevitable outcomes of the histories of the Dominican Republic and how they relate to Haiti and the United States. I am interested in exploring people’s relationships to themselves and each other as it relates to identity. Although I am involved with the representation of the many features of the place that I call home, I want to celebrate and critique different aspects of my story and culture.

XLB: In your newer works, there is a heavy use of green, pink, and blue. There is also a lot of direct, natural lighting. Through them, I can sense the vivacity of the tropical landscapes that Dominican identities emerge from, which continue to serve as a popular motif across diasporic geographies. The visual energy is consistent, whether or not you dot the painting with foliage found in the Caribbean. This is in direct contrast to your older works, in which you use more opaque, dim, indirect, and artificial lighting. These are somber and beckon weighty attention on the persons being depicted. Tell the readers what motivated these choices and changes in color and lighting.

RV: College is where I started developing my work. I was mostly influenced by the works of the old masters like Velasquez, Rembrandt, and Caravaggio. As I entered my MFA program, I was searching for a different feeling in the work and exploring ways of getting there. I didn't just want the work to look real or accurate anymore, I wanted it to have a feeling of its own, from within, that felt more close to what it is like to actually be in these settings. For example, I focused on details like the unpaved road where I grew up, how strong the sun feels on the island, and los ríos de Mao and their relentless currents. The motivation was a search for dynamism and vibrancy that was more accurate to the island.

XLB: Let’s discuss scene choices. Your paintings center human engagement with Caribbean nature in the form of trees, fauna, and mountains, with people either fully integrated into the landscapes or operating prominently in the background. The painting Homeowners (2022) is a slight outlier in that it shows a more contained and curated natural landscape and a housing style that signals suburban living in the United States. What motivated your choice to focus on this aspect of the Dominican experience?

RV: This painting was a response to what was happening at the time. My sister, with whom I immigrated with, purchased a home. The work is a depiction of my niece and nephew, centered in the painting, and the kind of lives they will live. I am aware of the intergenerational experiment of immigration and how children of immigrants have a very different experience than their parents.

It felt like one of those moments where the sacrifice of immigration felt a little worth it. It is a painting of celebration and it is full of hopes and dreams.

XLB: Is nature just the scene and are people the protagonist in your work or is it, at times, vice versa?

RV: I enjoy working through this question within the work. Of course, my main concern is people, however, context is everything. The overwhelming setting of nature competing with the figure creates a tension in the work that feels true to Dominican life.

XLB: Let’s discuss the body language of your subjects. You depict people with direct, serious gazes seemingly aware of the viewer or, less frequently, each other, in bodily positions suggestive of other, unprotrayed participants acting as spectators. There are also poses reminiscent of family album snapshots, commemorative working-class photo studio visits, and daily life street photography. Who are the artist influences of these choices of subject poses?

RV: For me the biggest influence is spending time in DR around my family. I get to be observant of people’s postures and poses, which I then bring into the work. Painters like Hopper and Manet influence my works in terms of the quietness and the gaze.

XLB: Is the “seriousness” of the people being illustrated connected to long histories of unsmiling picture takers across the globe, or a nod to a usually in-group conversation of Dominican and Caribbean cultural characteristic of photo taking? Or a mixture of both?

RV: The seriousness is both. Especially with the older generation, there is a seriousness in the way they pose for photographs. Within the work, I am looking to have the figure depicted in a state of quietness and vulnerability.

XLB: What motivates the decision to add smiles to your subject(s)?

RV: I don't add much expression to the figures that I paint. However, if the work that I am creating is based on a memory or based on my family album, a smile or two may appear.

XLB: What are some of your current projects?

RV: I am currently working towards a few exhibitions and art fairs. Most excitingly, I currently have a solo exhibition in London that focuses on my hometown of Mao, Valverde, Dominican Republic.

Xavi Luis Burgos is a longtime educator, writer, artist, curator, and organizer. He is a Ph.D. student at Stanford University, researching Afro-Caribbean religious traditions. He co-developed, curated, and moderated the symposium, “Afrorriqueñes,” exploring Afro-puertorriqueñidad between Puerto Rico and Chicago. He co-founded the ¡Humboldt Park NO SE VENDE! campaign, which worked to assemble resources and agitate consciousness of gentrification in Chicago. He was Editor-in-Chief of Que Ondee Sola, and published essays in Gozamos, La Voz del Paseo Boricua, Claridad, and 80 grados. Xavi is the co-founder and former Editor-in-Chief of La Respuesta, a publication that cultivated bridges between the diverse communities of the Puerto Rican Diáspora. In 2023, Xavi completed an art residency at Instituto Sacatar in Bahia, Brazil. Learn more about his work at: www.xaviburgos.com and Instagram: diasporapapi