The Laboring and Disposable Latina Body

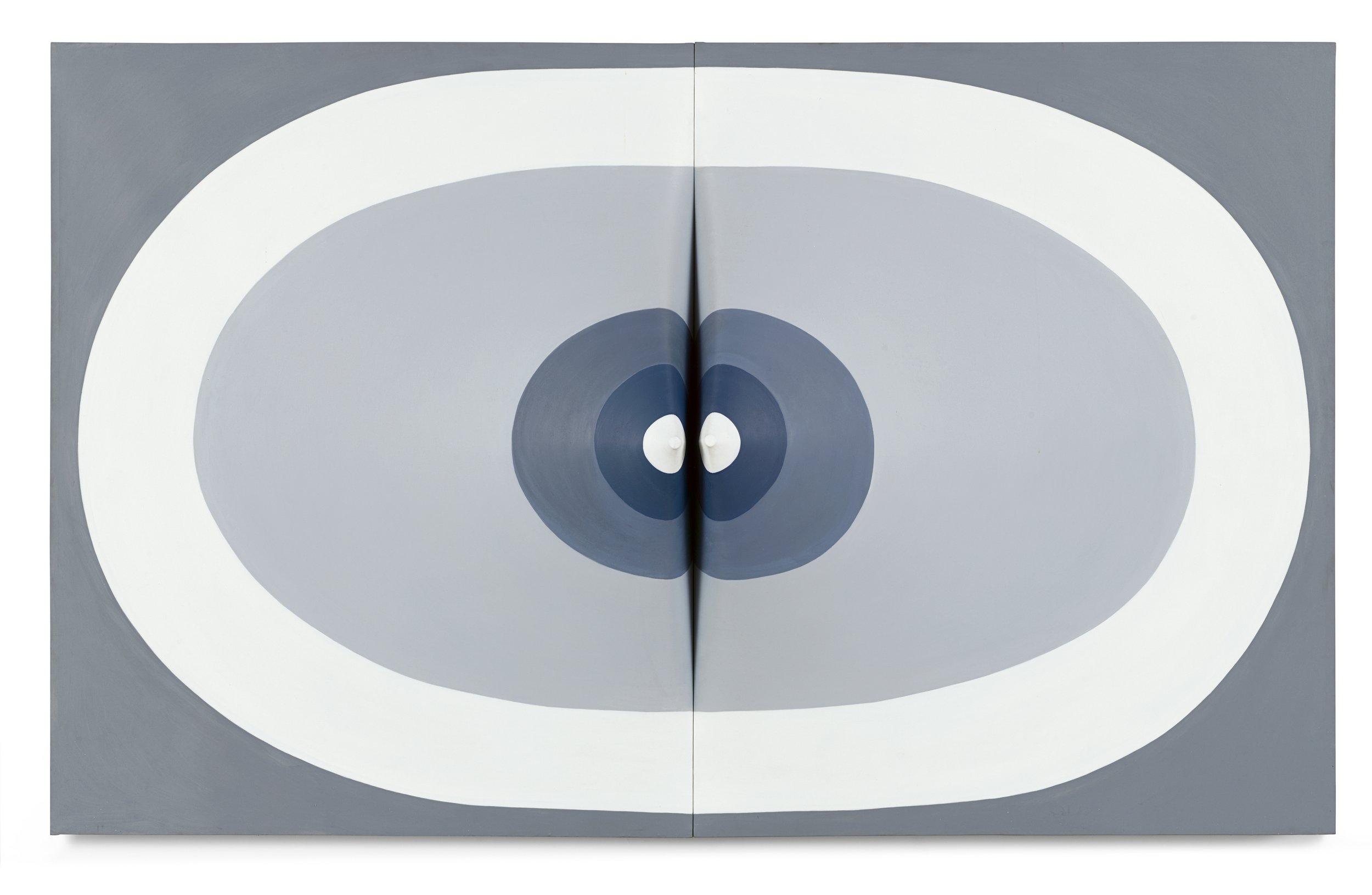

The blue and white of the painting undulate across the surface of the canvas, extending from top to bottom and imitating a figure with a rounded top. The structural construction of the frame gives the impression that the round form is jutting out—as if coming at the viewer. The white line that runs through the center of the painting creates a divide, a severance.

Zilia Sánchez’s art explores the nuances of the female body, offering opportunities for analysis on how society treats women and birthing people’s bodies as disposable and undeserving of autonomy. Antígona (1970) is perhaps one of the Cuban artist’s paintings that best relates to choice, both in name and practice. In Sophocles’s tragedy, Antigone had to choose between loyalty to her family and the wants of the state. Defying the state’s orders meant giving up the future possibility of a family, marking a purposeful separation between the body and future familial lineages.

“Zilia Sánchez’s art explores the nuances of the female body, offering opportunities for analysis on how society treats women and birthing people’s bodies as disposable and undeserving of autonomy.”

In the United States, various entities have taken women’s choice away countless times. In the 20th century between 1907 and 1939, fueled by the eugenics movement—which promoted the belief that selective breeding could improve the human race—non-white women endured decades of physical abuse through forced and nonconsensual sterilization procedures. In the 1950s and 1960s in Puerto Rico, women participated in clinical trials for birth control without having a clear understanding of what they signed up for. Through deceit, omission, and exploitation, they no longer had any autonomy, which led to trauma and physical harm in the short and long term. They were not alone. In the 1970s, doctors in Los Angeles were sterilizing Chicana women, robbing them entirely of choice. And recently, the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade (1973), ending birthing people’s right to choose to terminate a pregnancy.

With the Puerto Rico–based, Cuba-born artist Sánchez, we see work that gestures to the female body in its ever-changing forms, particularly in the series Topología Erótica (Erotic Topology). The artist began working on her trademark stretched canvases in the 1960s, running parallel to a period during which federal programs in the United States had begun to fund non-consensual sterilization, largely targeting BIWOC.

With canvases stretched over to create sculptural paintings and wood frames that depart from the traditional rectangular shape, Sánchez creates a structure that emulates the curves and surfaces of the female body. Though she could have remained faithful to a conventional, two-dimensional presentation, to produce her work on a flat plane would have flattened the work’s gesturing toward the female body. By creating three-dimensional pieces that extend out, she is not only challenging traditionalist ideas of what art should look like but also highlighting the varied ways that the female body exists and shows up in society.

It’s important to note that Sánchez does not consider her work feminist. “There has never been a feminist aspect to my work,” she told Ocula in 2016. “My work has always been very female, and I always thought about feminine, erotic forms when making works. Feminism feels too strong, too violent for me.”

However, as feminist Carol Hanisch states in her famed 1969 essay, “the personal is political.” She argued that societal position, particularly their political circumstances and gender inequality, are at the core of women’s experiences. As such, women’s bodies are political. Because Sánchez’s work revolves around honoring the female body in all its forms, it intersects with themes adjacent to or embraced within feminism. Speaking about her work, Sánchez has said, “I paint with feeling. And the feeling is inside. That’s how art is.” In positioning her feelings as central to the execution of her work, it could be argued that she is painting through her lived experience as a queer Latina, connecting her work to the theory of the “personal is political” and feminism.

Further, as a queer Latina woman, Sánchez occupies positions that have historically existed on the periphery of society, putting her work in conversation with Deborah R. Vargas’s theory of “lo sucio.” As Vargas contends, “Sucias are surplus subjectivities who perform disobediently within hetero- and homonormative racial projects of citizenship formations, projects that seek to rid their sanitized worlds of filth and grime.”¹ Sánchez’s subjectivity as a queer woman and her shaped canvases gesture to the female body in its ever-changing forms, with a particular focus on the Latina body that objects to sterilization, both physically and metaphorically.

“In contrast to the ideal human being that eugenicists promoted, women from Latin America who experience racialized, classist, and gendered violence, are often cast as dirty and nasty.”

In contrast to the ideal human being that eugenicists promoted, women from Latin America who experience racialized, classist, and gendered violence, are often cast as dirty and nasty. The body rejects, through phenotypic characteristics, what is socially acceptable or, as Vargas writes—following José Esteban Muñoz’s theorization of chusmería—“a form of behavior that refuses bourgeois comportment and suggests that Latinos not be too Black, poor or sexual, or any other characteristics that exceed normativity.”² By defining what is and is not normal, and rooting it in an Anglo-Saxon ideal, eugenics excludes bodies it deems offensive, i.e. Black and brown bodies.

In Sánchez’s works, the peaks that force the painted canvas to protrude are symbolic of these theories and the ways that some Latina bodies literally do not fit the prescribed standard—the conservative, Anglo-Saxon template of beauty in place in our society. Instead of attempting to fit within this ideal or “box” that purposely excludes, the figures that Sánchez depicts in her paintings, such as Mujer (de la serie el silencio de eros) (1965), proudly epitomize how some Latina bodies disavow those rules. That is, they do not subscribe to the set standards in their shape and size, instead creating their own space in which to exist. The painting features a large painted white circle with a bulge seemingly referencing pregnancy or buttocks, challenging how society routinely dissuades certain Latinas from taking up space, which is to affirm existence.

The juxtaposition of the solidity of the wood structure and the seeming “softness” of the canvas in Sánchez’s work is a celebration of the female body but also a reflection of the realities in which these bodies exist. The canvas stretched over the wood frame becomes taut but still retains its flexibility. Much like bodies that defy the societal framework of acceptable bodies like female bodies, those that exist outside the gender binary, and femme-identifying, it appears indestructible. In the context of the laboring body, the expectation is that it will continue to produce and is, therefore, valuable—so long as it is the right type of body. The right type of body not only means those that ascribe to a socially accepted idea of beauty but that also reproduce when acceptable.

Sánchez’s Untitled (2000)—a piece reminiscent of Georgia O’Keeffe’s flower paintings—further explores the female body, evoking the connection between her work, the practice of sterilization, and lo sucio. The stretched canvas creates several peaks in the middle, giving the impression of female genitalia, the part of the Latina body that, within Vargas’s lo sucio theory, is overtly sexual and flagrant. In the U.S., there has been and continues to be a perpetuation of damaging ideas about Latinas, particularly brown and Black Latinas from low-income backgrounds, reproducing at higher rates and being hyper-fertile.

Another piece that investigates the pregnant female body is Sánchez’s The Birth of Eros (1971), an interpretation of the female body. The wooden frame of the painting depicts two shapes, one round at the top and a crest on the bottom, further hinting to the reproductive nature of the female body. While the title alludes to the Greek male god Eros, his status as the god of love, sex, and procreation relates to the manner in which society sees some Latin American women as sexual deviants who procreate more rapidly than other groups. In their article, “Gender and Deviance in Latin America,” Jennifer Chan and Laura Aguirre Hernández write that the label of deviance both “creates and reinforces multiple forms of inequality and justifies symbolic, structural and physical violence against those that do not fulfill the social standards.” By referencing Eros in a piece that portrays a pregnant figure, you can make a connection between deviance and how it is violently conferred on Latin American women. The figure in Sánchez’s painting will birth Eros, alluding to the oft-promoted idea that Latin American women will not only procreate repeatedly but will produce bodies that will in turn also reproduce frequently.

Because of these harmful stereotypes, Latinas’ reproductive rights are in a precarious position, subject to strict ideas of female decency. Though critics often label Sánchez’s work as abstract, you can also categorize her figures as figurative. She retains elements that are inarguably representative of the female body, yet pulls, stretches, and minimizes them to produce radical reimaginings that mirror the diversity and expansiveness of the Latin American female body. By placing female genitalia front and center, and eliminating any vestige of shame, Sánchez transgresses the societal rules of decency and challenges notions of respectability.

Sánchez’s art presents the Latina female body as free—in direct opposition to eugenics and sterilization practices. It references the idea that the female body is disposable by focusing on body parts like the breasts and vagina. In presenting these body parts as isolated fragments, the female body is positioned as disposable within a capitalist society. An example of this is the painting Juana de Arco (1987). Featuring what appears to be a dramatically elongated female figure, it culminates at the top with two white circles seemingly depicting breasts. In illustrating these elements of female anatomy, Sánchez’s work foregrounds the parts of the body that keep the systems of labor going. The lengthening of the figure is reminiscent of a conveyor belt and its use in distribution. By portraying a lengthened figure, Juana de Arco creates a connection between how a conveyor belt’s purpose is the continuous movement of products and the position that immigrant women are placed in in which they produce for the state.

The claim of indecency also positions the body as a disposable entity. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States lured Latin American women with the promise of jobs and freedom, but they consistently faced exploitation via low wages, unsafe working conditions, and long hours. Their bodies—categorized as capital—labor time and time again for the country; when they are no longer of use, they are disposable. Paola Alonso writes that doctors labeled the women who were victims of reproductive violence as “sex delinquents” in their medical records. Society viewed them as “undesirable,” that is they were unable to provide the United States with anything of value beyond their labor. Doctors deemed sterilization “necessary to protect the state from increased crime, poverty, and racial degeneracy.”

While we’ve seen the abolishment of sterilization laws throughout Sánchez’s career, women continue to experience a lack of autonomy as the U.S. government wields power over their bodies. In Sánchez’s work, however, we see women’s bodies front and center, taking up space, molding the contexts that surround them, and living as they please. Sánchez’s work rejects both the archaic conventions of respectability imposed on Latina bodies and the charges of indecency Western society uses to justify physical and emotional violence. Through her various figures, Sánchez’s work honors the multifaceted ways that women’s bodies exist and walk through society. Moreover, through her canvas structures, she foregrounds how despite the failure of the government to protect Latina bodies, they continue to survive and, more importantly, flourish.

¹ Deborah R. Vargas. “Ruminations on ‘Lo Sucio’ as a Latino Queer Analytic,” American Quarterly, 66, no. 3 (September 2014): 718.

² Deborah R. Vargas. “Ruminations on ‘Lo Sucio’ as a Latino Queer Analytic,” American Quarterly, 66, no. 3 (September 2014): 715.

Karla Méndez is an arts and culture writer. She is a lead columnist for Black Women Radicals, a contributing writer for Elephant Magazine, and has written for Burnaway, Polyester Zine, and Ampersand: An American Studies Journal. She writes about the histories of Black and Latin American women and their representation in visual art, performance, and poetry. She holds a master’s in American Studies from Brown University and a BA with honors in Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of Central Florida.