“Where We Were Safe”: Mapping Resilience in the 1970s Salsa Scene

"Just like today, [in the 1970s] the police killed Blacks and Latinos as nothing," said journalist Aurora Flores over Zoom during last summer’s protests following the murder of George Floyd. "So going to the rumbas at Central Park was like a refuge, a liberation," adds Flores, who can't help but see parallels between the abrasive 1970s and a present-day reality also fueled by the COVID-19 crisis. "Today, no one can go to the rumbas. Do you know how many hands touch those tumbadoras?"

That same summer, Mickey Melendez, a Young Lord who was deeply involved in the Latin music scene since the 1960s, reflected on the importance of keeping and developing cultural spaces amid violent times. "When you are in El Barrio, any Barrio, you are safe [...] Once you step out of El Barrio, now you are stepping out into the world, you know? So one way of looking at these spaces that you are talking about is that we created our own little barrios wherever we went to be safe in them." The places we were referring to are the historical sites of Salsa music—venues, record stores, theatres, and public spaces—now disappeared or destroyed.

Both Micky's and Aurora's testimonies provided insights to something that I started researching in Fall 2019: the deep connections between Salsa, territory, and community. My objective was to discover how these disappeared sites—part of the Latin cultural heritage but overlooked in New York's traditional history—helped the community develop resistance dynamics in the abrasive 1970s. As I explored possible answers to this question, I found a complex narrative intertwined with structural violence, resilience, and Latin pride.

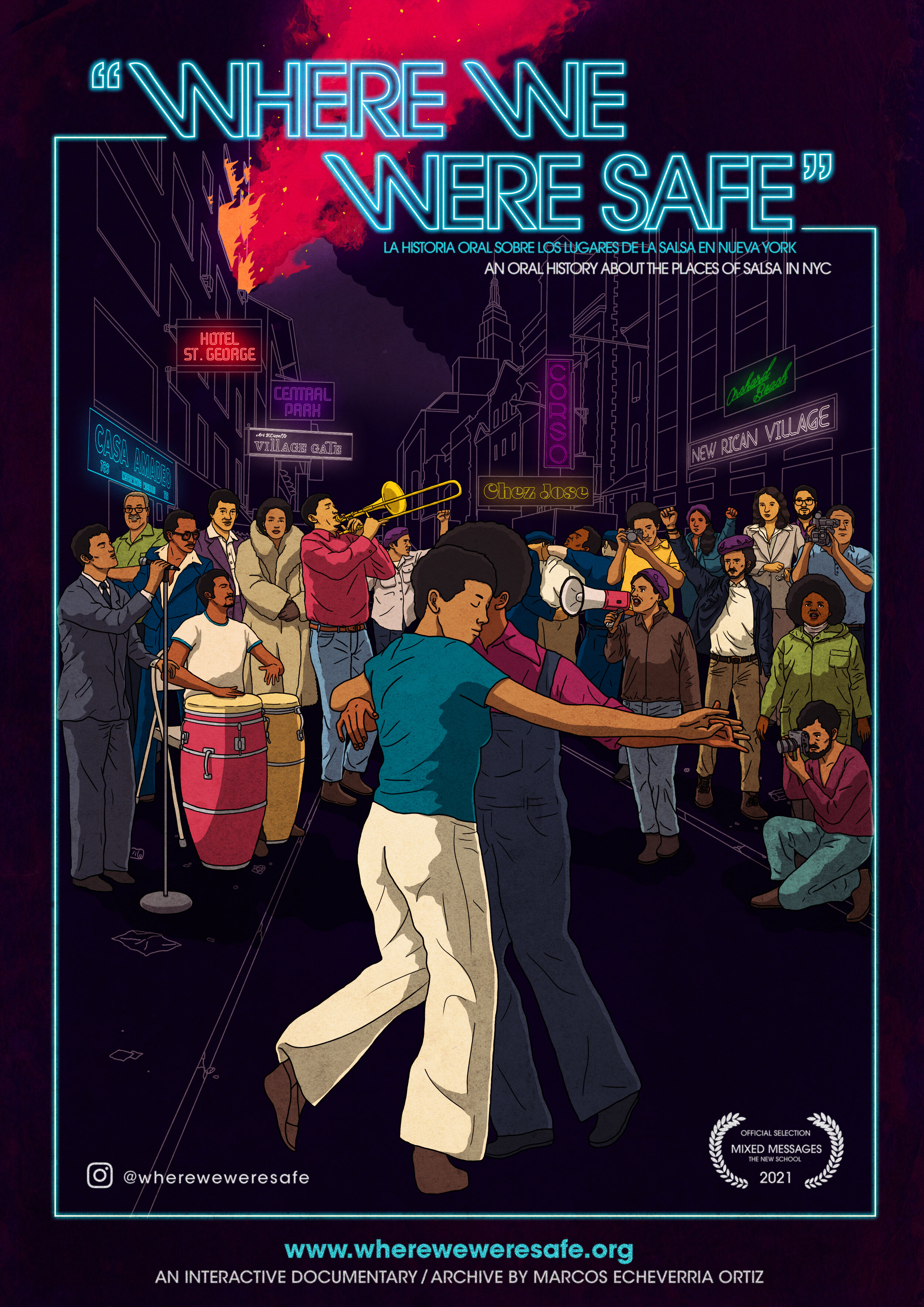

Where We Were Safe

Although New York has been a Latino city for more than a century, official records exclude and overlook the strong connections between territory and this community's presence in the historical record. The maps used to develop redlining, urban renewal plans, and slum clearance were used throughout the 20th century as tools of oppression. They targeted and erased Black and brown cultural enclaves. For this reason, it is alarming to still not see Casa Amadeo in the city's official landmark map, despite being part of the National Register of Historic Places of the US and recognized by New York state as a historical landmark. If Salsa was one of the most potent and meaningful Latin expressions in New York City history, what happened to their historical places? Why are they not recognized, preserved, and acknowledged? To rebuild a fundamental part of this city's cultural experience, I decided to map, discuss, and preserve the disappeared landmarks of Salsa music.

"We Were Safe" is an ongoing interactive oral history map/archive that focuses on collecting memories about the lost and destroyed Salsa music places in New York City, such as ballrooms, clubs, record stores, and outdoor venues. Through digital mapping and cultural memory, it aims to reconstruct historical space and recover these sites' heritage through a lens of social, racial, and cultural dynamics that fed the Latin experience.

This project concentrates specifically on the 1970s for two reasons. First, this decade was fundamental for developing "Salsa music" as a musical form and culture in New York City and Latin America. Second, during this decade, African-American and Latin barrios felt the effects of violent urban policies that pushed them to organize social and civic movements against racism, police brutality, and urban decay. For this reason, this project approaches Salsa as a cohesive cultural force to understand how it negotiated ideals of Pan-Latino identity in New York City. Under this context, I defined "the places of Salsa" as historical sites, private and public, where not only salsa music was performed but also where the Latin community knit social dynamics of cultural resistance.

Finding the Places and People Who Inhabited Them

There is no official document that maps the historical places of Salsa. One close approximation is Roberta L. Singer and Elena Martinez's investigation about theaters and other mambo music venues in the South Bronx during the first half of the 20th century.

My main interest was the 1970s, so after intense research—documentaries, books, records, Youtube videos, blogs, fandom sites, and some initial interviews—I identified more than 100 sites. Unfortunately, all of them, except for the Casa Amadeo and Casa Latina record stores, which members of the community still own, are entirely obliterated.

Archival material about these sites was limited, almost nonexistent. However, I retrieved some photos and videos available online on social media and fandom blogs. Most of this content is recycled by different accounts, which suggests scarcity. Also, it was common for images not to have citations nor proper categorization. This causes three problems. First, it overlooks producers and authors. Second, it makes it difficult to give them adequate contextualization. And third, it directly affects the preservation, distribution, and management of these historical items in the digital realm.

Meanwhile, the Covid-19 crisis blocked any possibility of in-person archival research. Digital collections of important historical and education institutions such as New York Public Library, Museum of the City of New York, and others had limited items on this matter, which shows how under-archived and under-preserved this part of Latin history is. Nevertheless, El Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños at Hunter College and Cornell's digital archives had some meaningful materials.

Because of these limitations, memory became the core of the project. Rather than a nostalgic approach, it gives communities a sense of continuity and the agency to manage, recreate, and understand their past. Therefore, I utilize memory as resistance to preserve a collective knowledge under discussions framed by historians such as Piere Nora, Jass Assman, and others. For this reason, as an oral history archive, Where We Were Safe preserves the voice of ordinary people. I was interested in characters often obscured behind the shine of Salsa stars. People who experienced the lost places at the dance floors, in the bathrooms, behind curtains, or under the stages. After months of locating potential characters and creating a list of nearly 40 names, I interviewed 18 participants, including dancers, academics, journalists, photographers, videographers, DJs, bouncers, fans, political activists, and some musicians directly involved in the Salsa music scene.

Rendering A Map of The Resistance

Inspired by social cartography, I was interested in applying non-traditional mapping approaches. For this reason, participants had the agency to create their own socio-spatial relations. They talked about their experience while growing up in their barrios, the other areas around the city they frequented, and the meaningful personal locations and landmarks that made them feel celebrated.

After almost 1,080 minutes of spoken testimony, registered within four pandemic months, the testimonies ended up rendering personal oral maps that simultaneously, generated a collective territory experienced in the same eight places: Casa Amadeo Record Store and Orchard Beach in the Bronx, El Corso, and the Chez Jose clubs in midtown Manhattan, Bethesda Fountain in Central Park, The New Rican Village in the Lower East Side, The Village Gate Club in Greenwich Village, and St. George Hotel in Brooklyn.

The selection of these landmarks highlights factors such as location, audience, and affordability. First, these sites were located all around the city, evidence of how dense and active the salsa scene was. Trombonist Papo Vazquez recalls playing every Saturday night in three different clubs in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. "That is the sad thing about New York. That time no longer exists, and there are no such places anymore. At that time, there were at least 50 different nightclubs, and each club had at least two or three bands."

Additionally, location informed some urban tensions defined by class between the uptown and downtown dichotomy. Salsero Pete Bonet, who managed the famous Corso Club in the late 1960s and early 1970s, said: "Men had to come well dressed. They couldn't come with a shirt. Here just entered the cream, the good people. Los titeres who came in sneakers or majones could not enter the Corso." In contrast, public spaces such as Orchard Beach and rumbas at Bethesda Fountain in Central Park contest these class conventions. Salsera Daisy Fahie remembers that Orchard Beach, once occupied by only white families, was reclaimed by the Latin community thanks to Ernie Ensley's Salsa Sundays. "Latinos finally found a place where our community could come together to chat, dance, and see orchestras. That is why they call Orchard Beach—the Bronx Riviera." Additionally, original Central Park rumbero Felix Sanabria recalls how Afro-Caribbean sounds performed in an open public space became a statement of pride and existence: "For me, rumbas have been a reason to say that I'm someone, got it? That I'm part of the nation and the community, that I'm not marginal. It gives you meaning."

Second, although all these Salsa places were part of the same Latin Music ecosystem, they responded to different interests and welcomed different audiences. This helps to understand the relation—or distance—between an older conservative audience and a newer generation of young Latinos interested in counter-cultural ideals. Photographer Máximo Colón, who has documented the Latin music scene since the 1970s, said that The New Rican Village was a place for "Students, militants, and intellectuals—a place for people from our community involved in cultural and political stuff." This audience was known as the sneaker crowd: young Latin college students interested in politics, social justice, and Latin pride. Young Lord Mickey Melendez adds that unlike any other traditional salsa club, "this was a place for left Latin cultural development. It really took the Nuyorican cultural experience to a place where you can experience different things [poetry, theater, and music] under one roof." For this reason, the avant-garde Latin sound of the late 1970s—bands such as Conjunto Libre, Salsa Refugees, and Fort Apache—performed here.

Third, depending on the site's location and audience, each allowed for racial integration, a sense of dignity, and education. For example, the Village Gate club, located in Greenwich Village, endorsed racial integration between Latins, Blacks, and whites by integrating two musical scenes: Jazz and Salsa. Salsera Daisy Fahie remembers that "when Latin music started, we danced and enjoyed ourselves. I mingled with Chinese, Blacks, and Whites; with teachers, doctors, and lawyers. Latin music brought people together."

The Chez Jose, located in one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in midtown Manhattan, provided a comfort level and a safe space for the community. Former owner Arnie Segarra recalls that the most important thing about this place was "To see your people, your blood, your generation enjoying themselves, forgetting about the hardships. There is something about that. [...] Pride, dignity, and you were with the rainbow people: dark-skin Latinos, black skin Latinos...and the respect for each other."

Uptown in the South Bronx, Casa Amadeo Record store provided a safe space while the neighborhood was burning. "Mike [the owner] helped a lot of people. And he was there while the Bronx burned. He was there...And he supported the youth that was disconnected from Latin music. In what he sold, he taught me a lot, and I learned a lot from him," explains DJ and salsera Carmen Cepeda.

Testimonies like these weave a narrative that situates salsa's landmarks as cultural ecosystems that helped a generation to resist and celebrate their existence mientras todo se estaba derrumbando. The memories and some found visual evidence are archived in 65 short video vignettes that can be accessed through an interactive map, a repository of the participants, and a section that organizes the testimonies into seven topics of resistance.

Pa’lante

Who is left behind? As a map/archive of the past, it is necessary to recognize its incompleteness. However, this allows Where We Were Safe to be a living archive with the potential of incorporating other underrepresented voices and un-archived pieces of the past.

Salsa has historically gravitated around macho-centered perspectives, which have over exoticized and commodified Latin and Afro-Latin women. This violence is addressed in the archive by journalist Aurora Flores and DJ and salsera Carmen Cepeda. They report how misogynistic and toxic the environment of some clubs and venues was. As a project that maps dynamics of resistance, it is fundamental to extend this discussion to challenge normalized misogyny in Salsa's golden years. At the same time, there is no mention of the role of the LGBTQI+ community. Although this group is often linked to the Disco and the Ball subcultures of the 1970s, it is necessary to examine their perspectives, purpose, and experience during the development of Salsa music in New York City.

The immersive component of the project allows you to visit these places, and to see how they have changed or disappeared in the chameleonic city.

The eight places included in the map are starting points to understand Salsa's landmarks and their creation, development, functionality, and later, disposal. However, it is also relevant to archive other venues in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and El Barrio. In addition, I plan to include record stores, theaters, magazines, radios, and record labels often obscured by the metanarrative of the Fania empire, but that was central to developing Salsa as a cultural expression. For this objective, finding future funding is a requisite.

An archive that does not promote reinterpretation, critique, and reproduction, is dead. For this reason, I'm interested in forging educational partnerships with schools, museums, and community centers to use this project as an educational tool to encourage the critical reinterpretation of the past.

Finally, when is it enough? When to stop talking about and archiving the past? Western culture is overpopulated with institutions and media projects that aim to remember. However, remembrance is a privilege of hegemonic culture while some other communities struggle and fight for having "history" in the first place. The "boom of memory" does not have the same political implications for everyone. For some groups in the United States, memory production can be romantic, nostalgic, and even cliché. For others, remembrance and repetition could be the right of existence. For this reason, I hope that "Where We Were Safe" empowers communities to record, promote and preserve their contested or manipulated narratives. It is fundamental to restore practices for self-representation through storytelling as a powerful and honest way to ensure historical continuity.

Marcos Echeverria Ortiz is an award-winning multimedia journalist, photographer, and documentalist. For the last eight years, he has invested efforts to develop transmedia projects and cover stories related to culture, music, social movements, immigration and human rights. Originally from Ecuador, through Noisey VICE, Radio COCOA and others he has written, filmed, and photographed the underground and independent music and cultural scene of Latin America. Marcos graduated with honors from the Media Studies MA program at The New School. He has recently covered social justice movements and worked with organizations such as Make The Road New York, United for Respect, among others. His pictures have also appeared in Business Insider and The New York Times. Through documentary and hybrid forms of media, he chronicles the Latinx experience in New York City through stories interjected by music, inequality, memory, and history.

Where We Were Safe credits: Marcos Echeverria Ortiz, director; Amir Husak, Neyda Martinez, and Fabiola Hanna, advisors; poster design: Sebastián Valbuena.

Participants: Special thanks to Orlando Godoy, Aurora Flores, Máximo Colón, Mike Amadeo, Arnie Segarra, Mickey Meléndez, Carmen Cepeda, Robert Iulo, Noel Quintana, Pete Bonet, Ricky Flores, Luis Berrios, Liz Cartagena, Daisy Fahie, Papo Vázquez, Félix Sanabria, Yeyito Flores, Robert Gotay, and Gerson Borrero. Also, thanks to Salsa and Latin American music fans on the internet, whose work and passion make our history less restrictive.