Bateyes del Chibal: An Interview with Jorge González

From within the four walls of his studio, Jorge González is continuously building a place for gathering where the sharing of knowledge transcends time, space, and uncovered narratives about our indigenous histories. Merging various aspects of his practice, his site-specific installation uses locally harvested and woven plant fibers to create walls and a wooden altar—all acting as a central hub for traditional ceremonies and communal events. As part of Protocinema’s multi-city group exhibition, “A Few in Many Places,” González presents his take on sustainable exhibition-making models through his collective pedagogical platform Escuela de Oficios (trade school). The project, entitled Bateyes del Chibal, focuses on engaging with communal belonging within the context of ceremonial plazas called bateys by indigenous and Afro-descendent people in the Caribbean. Now planning the final events around this project, I spoke with González about his experiences and concepts.

Sebastian Meltz-Collazo: I feel that your projects flow in an organic way, where your concepts and thoughts overlap in continuous form from one thing to the next. How did you land on your ideas for Bateyes del Chibal?

Jorge González: It was a process of recognizing what we had been working on with the idea of the collective house, which took shape as projects related to Edwin Marcucci, his farm and his resources. And also considering his knowledge, as one of my firsts teachers with regards to my relationship with natural fibers. He opened many possibilities within collective processes, giving beginnings to a community learning space, which at the same time was consolidated with ideas about self-managed education. During that process at Edwin's farm, there was the notion of relating to the resources that were around us, and within that was the batey—thinking of the batey as a resource available to all of us. For me, it was very interesting to generate that approach and reflection and, at the same time, recognize how it [the batey] survives in the knowledge of many people. And so the Chibal aspect of it is oriented towards the recognition of the Canjíbaro thought, which makes a link between Puerto Rican culture and Mayan culture. There is much that is present in the Yucatan region, elements that inform the reflection on certain experiences of growing up in the interior of our island. These are ideas that a researcher organized, then developed and affirmed with a community. From there emerged a self-determination of its own, which is the Canjíbara, displacing all “official” narratives about the indigenous in Puerto Rico. I am very interested in it because it creates links of cultural development beyond our borders; the sea is understood as a place of exchange and the possibilities of broad participation open up. It places us in a context of confluence.

SMC: What purpose can a Batey carry in our society today, and more so, what does an areyto (ceremony) entail in the form of the events you have been doing these months? What do you celebrate or propose to offer?

JG: Uahtibili Baez, who recognized the batey at Edwin’s farm, connected it with the experience and relationship that he and his family have with the bateys of Caguana. Within his family memory and ancestry, he has access to these spaces because of the ceremonial use of the Caguana bateys. It is interesting how a ceremonial center involves time and form, where there can be a cosmological relationship about space and understanding the world through it. It is also aligned with the natural cycle, which enters into our long-term conversations about the Maya calendar based on the studies of Pedro and Elsa Escabí. They led us to think about this program through the chant of the rosary, which is a ceremony that recognizes the natural cycle, in celebration of nature and giving thanks to the earth. It is interesting that Bateyes at the same time works closely with the development of Escuela de Oficios, such as this itinerant program with a mobile structure. We are sharing knowledge, in transit through different parts of the island, through Bateyes. And so the areyto enters into several functions through this invocation of what’s ancestral. We celebrate being able to convene in a space of training and education, where remembrance is part of collective learning. Empowerment also arises—to fight with strength towards where we want to go. And taking into account these references, recognition is also given to Afro-descendants and how they contribute to the development of this space. It serves as a space of vindication. Just think of bomba in its actuality, and its anti-patriarchal practice where the queer or transgender person dances as resistance! That is a very proper place towards the ancestral function of bomba as a cultural manifestation.

SMC: You recently had a meeting where you invited people to walk to a cave in Río Encantado. Can you talk about that day and how you organized the different elements to create this procession?

JG: Well, we developed a small program around the solstice that brings together many intentions. It is small within the framework of the overall project, but we did an organized transit between Ciales and Manatí, walking from the source of the Río Encantado to its mouth at the Rio Grande de Manatí. There in that space our batey was formed, celebrating many things. It was a very beautiful gathering, and this is something that is built over time as a community, with clear intentions. We achieved a moment where one of our teachers, Jasmine Rivera, was able to celebrate a tejido (weaving) that was produced in another community, where she imparted her own knowledge back in 2016. Five years later we see the fruit of our conversations and our exchanges of knowledge. So these are processes of small transformations that, when the day of the walk arrives, the celebration carries a lot of weight in its significance.

SMC: Like you said, it commemorates that passage of time and the conversations that emerged during those five years. It makes me think about how organizing the batey is its own resource, making this space available to share knowledge and unite us in resistance.

JG: Yes, and so we also think about the oppression that has been lived through for so many generations. When you keep your intentions clear, therein lies the strength of the areyto, from what you want to call to reclaim and keep in mind.

SMC: In a way these events are a reclamation of this historic ritual of reclamation itself.

JG: Precisely, and with the Goyco Community, something very special happened with the chant of the rosary. For me, one of the most beautiful things is that it gave us the grounding to be able to operate within Santurce, and it connected us with my harvest of resources in Canóvanas. That made even more evident the connection that has existed for so long between Santurce and Loíza. There is something in that process that strengthened me a lot to do the activities in my studio, to build an altar and the walls to act as a contemporary batey. We were able to count on this community that has been organizing these festivities, which had not happened since before Maria. It was nice to be able to set up that altar, because in doing so it became a process where I honored the resources that I harvest and use. And I gave these [resources] as an offering through these festivities so that the land can continue to bear fruit. On the other hand, it was also a time to process the losses that we’ve had, whether due to COVID or other circumstances. I saw it as a time to honor the memory of Elsa Escabí. It all felt very full circle.

SMC: What was your process choosing the materials you used to create the altar and the walls in your workshop?

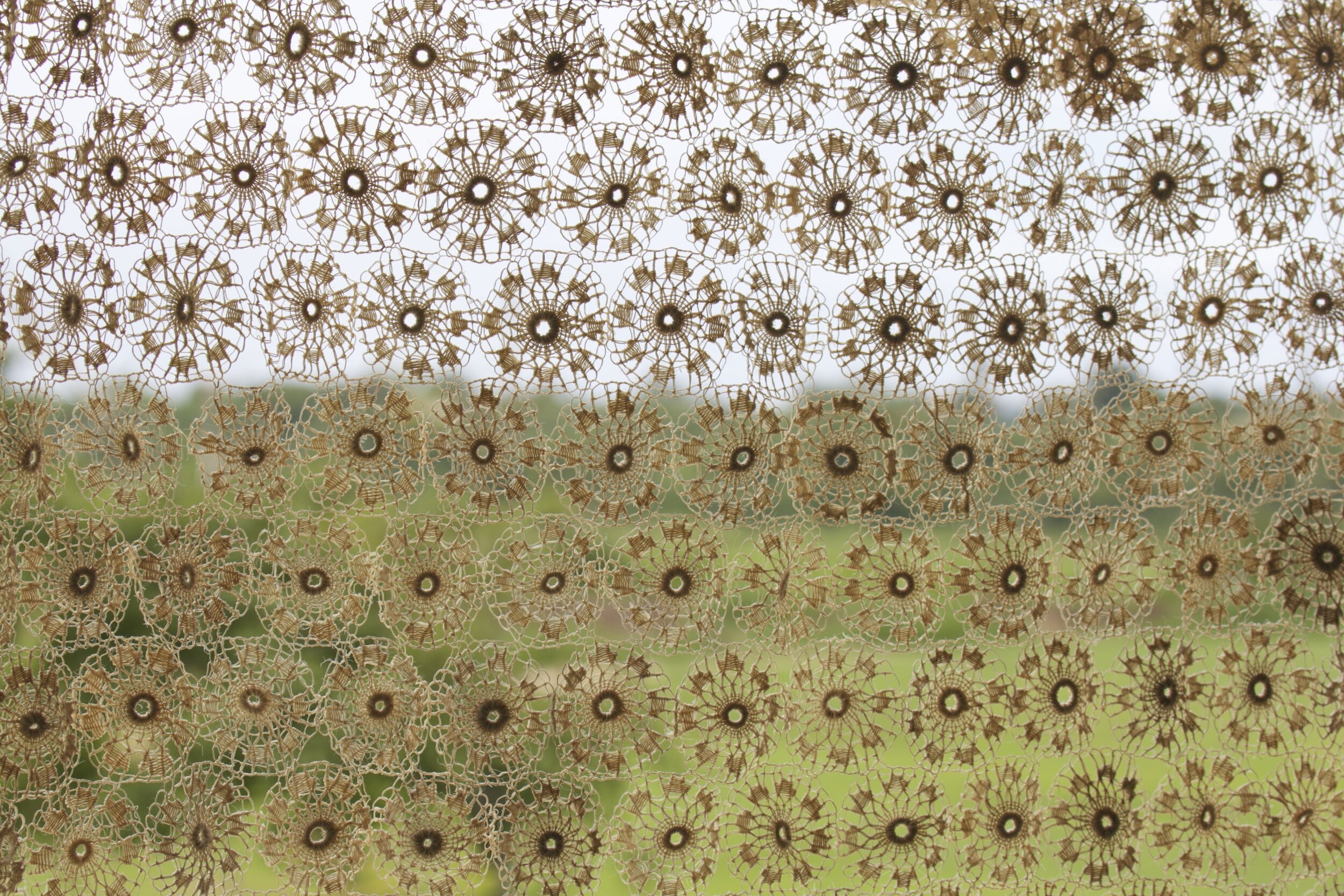

JG: I’d say that the exhibition I had with Embajada in 2017 still informs my thinking, because it was like a first statement about the Antillean calendar. And then thinking in continuity about the collective house, literally surrounding ourselves with the branches and plants surrounding us, that are already there and creating a structure based on those materials. It is knowledge that has been maturing: the weaving we have achieved to place the flowers, the autonomous process where I no longer depend on processed wood, the walls made of yagua (palm tree stems)... They are based on long-term conversations about resources that are gathered in an ethical way.

SMC: The same goes for the bamboo and the mud you used for the walls...

JG: Yes. In fact, for July 10th, Ernesto Pujol brought his students to my studio to do a mud stomping workshop! He contributed a lot towards the thought process around the procession we had. He helped us to think about the use of these resources and to orient them towards the creation of a myth, where we compile all of the knowledge, resources, and narratives that have brought us here. And that happens through the weaving blanket that was presented, which embodies what travels, what arrives, what is cared for and its intentions over time. I think the altar at my studio also has elements that point towards the creation of this myth that connects us, they are like custodians of that place and event. So yes, everything is collected in the same place, the mud, the bulrushes, the yaguas. It runs behind the Piñones forest which connects us with those histories.

SMC: It's very beautiful to hear how you describe where the materials come from. The thought and care you have about it makes it evident that within your works you create a very intimate dynamic where you create a piece of material art in relation to its purpose towards the event, the non-material side of the work. And so your proposal always carries an element of collaboration or revolves around a growth in community. What aspects of your life and environment lead you to continue to work in this mode—is it in response to certain realities?

JG: I think of the structure of the Trade School as one that assembles, disassembles, and creates situations of cohesion. My work is geared towards enabling collective learning spaces, taking into account the deterioration of school systems since 2016. There has to be a priority on the issue and a commitment to generate those collective moments. It is also to commit ourselves to the knowledge that is shared from a place of generosity on the part of the artisans and other collaborators involved. It is important that there is a cultivation of techniques, but beyond that, the commitment is with the connections and that sense of generosity, enabling new ways of understanding each other. As you see with the weaving, this has expanded from Puerto Rico to Colombia and Mexico, to name a few [countries]. This creates networks of support at different scales. Personally, I continue to grow technically, but being able to distribute my authorship and put myself within the collective context motivates me a lot.

SMC: How do you think about your work in the context of this exhibition—the dynamic that is created by presenting something very local to a global audience? Do you think about how that exchange can affect what’s local as a result of your exhibition?

JG: Yes, it's actually been one of the richest experiences I've had, in a moment where the organizers are thinking about providing resources and creating an economy to incentivize practices. We have been able to address the violence embedded in artistic production that’s often overlooked—whether we’re thinking about the materials we use for our artworks, where they come from and their sustainability, the costs and repercussions of shipping works, etc. I already had a link with Abhijan Toto, from when we met in India before the pandemic started. We met for the Under the Mango Tree program at a university where they teach pedagogy surrounded and inspired by nature, so the classroom is often under a tree. And when this event was conceptualized, the notions of solidarity, generosity, and empowerment were felt across the different geographic locations participating at the same time. Abhijan, together with Mari Spirito, made us think from an ecological standpoint, where there was no physical circulation of works but various local communities were encouraged to gather and create. I am very grateful for the project, how it connects us in this specific moment, and I think there should be more programs like this.

Sebastián Meltz-Collazo is a writer, visual artist, and musician working towards new experiences through the intersection of narratives. Connecting personal with collective histories, he explores iterations of visual culture and representation with the intention of raising questions around identity and its various manifestations. He is a graduate of Image Text Ithaca and is based in New York & Puerto Rico.