The Sacred Geometries of Yanira Collado

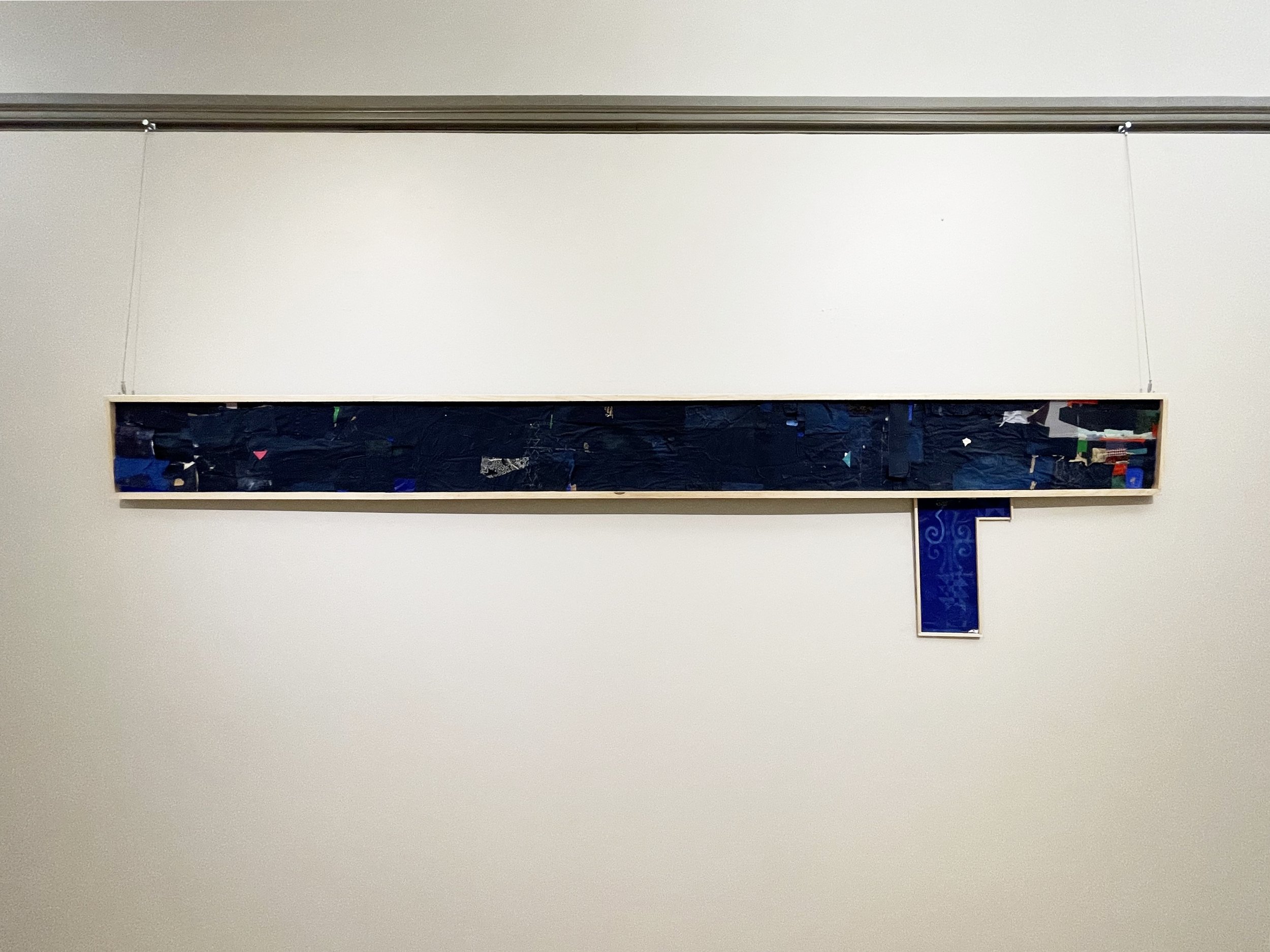

Through rigorous study, assemblage, and exploration, Yanira Collado eloquently transforms commonly-found, desecrated objects into profoundly beautiful poetry. As the proverb says, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure,” but in Yanira’s case, her findings are elevated to a sacred state. As I look at her exhibition Areíto: Allusions of Sacred Geometry and Diaspora, I am more and more convinced that these artifacts were made to be studied by us and the world. Areíto is an Arawak ceremonial practice that was believed to recount and pay tribute to the heroic deeds of Taíno ancestors, chiefs, gods, and cemis. Most of the elements of this exhibition are derived from the many cultures that embody what we know as the island of Quisqueya, popularly known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

I had the pleasure to engage in conversation with Yanira a few weeks ago, in preparation for this interview. We talk about her upbringing, her college days, her connection to Chicago, and her current exhibition.

Edra Soto (ES): Your Dominican roots are palpable and celebrated in your practice. Please tell us about your upbringing and how it has influenced who you are today.

Yanira Collado (YC): My connections are grounded to an alternate imagination: a Caribbean imagination and an alchemic consciousness. The Dominican Republic is a culturally rich country. Our musical narratives, folkloric traditions, oral histories, spiritual and supernatural beliefs are complex and embedded in our everyday life. All these components shaped my perceptions, sensibilities, and life experiences. I am always seeing the world through a Caribbean lens.

Memories of my infancy come to mind when I think of influences. Images of detritus, colorful lint, industrial sewing machines, fragments of tattered textiles. Also, visions of construction materials like plywood, cinder blocks, drywall, etc. I am referring to my parents' immigrant experience of working in garment factories. Many of these places were built by my father as temporary spaces of work for other migrant workers. My observation of this specific type of labor, the velocity of fabrication and methods of assembly greatly impacted my disposition. My awareness of this experience allows me to reflect on that past and drives much of my visual output.

ES: Being a School of the Art Institute alumni made me so curious to learn what made you decide to come to Chicago to study at SAIC? How was your experience as a student in the early 90’s living and working in Chicago?

YC: Before Chicago, I attended New World School of the Arts, a magnet high school in Miami, FL. That environment encouraged me to pursue art with an interdisciplinary approach. Given my interests in materials and cultural studies, I did not identify as an artist who desired to speak only in one medium. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago complemented this experience for me but also introduced me to so many other resources. I was also interested in the idea of living, studying, and challenging myself outside of a tropical environment. It gave me the ability to immerse myself in a completely different experience where I could grow as a person and artist. When I arrived in Chicago, I was captured by the architecture of the city. The dying and resurrection of the flora as the seasons changed seemed so poetically remarkable. The one noticeable and consistent marker of discomfort was that my Caribbean cultural practices, conduct, and methods of conveying information and idiosyncrasies, seemed to be a point of unease or displacement for others at times. It was internally challenging to feel so apart from my fellow study mates even when engaging in fellowship.

ES: Your current exhibition Areíto: Allusions of Sacred Geometry and Diaspora was mostly built and crafted in a studio at the Noyes Cultural Center in Evanston. Please, share with us your connection to Evanston and the community that is hosting your remarkable exhibition.

YC: I lived in Evanston for two years while working for a family and attending SAIC. The Noyes Cultural Center holds many dear memories for me. It is where I first started teaching and learning the relevance between the practice of art making and being of cultural service.

This exhibition, in many ways, was about reconciling past circumstances and experiences in Evanston. It was a way of reaching back while I stood in the present. It felt like a familiar essence coexisting with ghosts as we endeavored to create a project intended to be gifted to the community. Many of the sculptural elements in the exhibition were reclaimed from the actual home I once lived in almost twenty years ago. So, there are many layers that resonate in my connection to Evanston. bell hooks once stated, “we need to document the existence of living traditions, both past and present, that can heal our wounds and offer us a space of opportunity where our lives can be transformed.” This is something I always meditate on.

ES: The sacred geometries and diaspora themes you presented at El Museo del Barrio as part of Estamos Bien for La Trienal in 2020–2021 are a part of this expansive project you have been developing for the last 5 years. In your artistic statement for this exhibition, you explain that your work is “an analysis into the emergence and diaspora of the cultural practices, spirituality, and folkloric traditions in the Caribbean.” Can you tell us how tradition and cultural and historic manifestations collide visually and conceptually? What are the internal dialogues that recur during the artistic process?

YC: Many aspects of culture and history overlap and tend to get intertwined, but there is always that universal consistency represented through geometric principles. Geometry can be located anywhere and everywhere: in architecture, textile design, biology, galaxies and micro-verses. I tend to gravitate towards and investigate sacred geometries. I am invested in retaining cultural values and traditions by encoding their meanings through a symbolic process that produces abstract forms. Geometry is already part of our spiritual dialogue. I am just trying to reassess what is already there and highlight/rectify its plural purpose. This often results in various methods of layering and partially revealed elements. Components such as debris, fragmented materials, written content, geometrical forms, and objects of emblematic meaning are layered. The layering is an attempt to introduce those bits of narrative that may have not been previously considered and in conjunction (due to its veiling), keeping these elements from being vulnerable to distortion.

ES: How is architecture and place manifested in your collage and sculptural work?

YC: There are many geographic and ethnographic components for me to consider when assembling an architectural idea. In these constructs I am revealing the structural sensibilities and cultural values associated with their place of origin, alluding to the process of the assembly and erosion of these structures. Just as civilizations are constructed and organized, they are also vulnerable to disintegration. Like a cartographer, I am interested in temporal lines linking both horizontal and vertical points that connect the meaning in those structures, their power, and history.

ES: Your work collects, collides, juxtaposes and renders a constellation of materials from a variety of sources. Please, tell us about the materials that you use to craft your collages, paintings and sculptures. Where does the material come from and how does it inform the work? What are the characteristics of the material that make you consider its value?

YC: First there is my regard for the fragment. Fragments are artifacts that in their incomplete nature become critical pieces for reassembling histories. The conservation of ancestral narratives of our culture(s) is dependent on what fragments survive the passage of time and human interference. I’m interested in the alchemic transcendence cultivated in discarded materials. All materials have origins and retain the residue of their past purposes and function. In my attention to these fragments, I want to rouse and create a repository for their essence. Geographically, some materials charged with a spiritual cadence originate, for me, within the Caribbean. For example, Cuaba soap, which is used to deflect hexes. Ground ginger is used for its healing purposes and amber for its preserving qualities.

ES: What are some of the things that are capturing your attention lately?

YC: Zora Neale Hurston once said “Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose.” The lure of geological research has been a focus of delight and wonder for me for the last two years. The possibilities of studying the earth's organic architecture, substances and the processes that shape it are an infinite stream of inquiry.

Yanira Collado: Areíto: Allusions of Sacred Geometry and Diaspora is on view from March 25 to May 18, 2022 at Noyes Cultural Arts Center, Evanston, IL.

Puerto Rican born, Edra Soto is an interdisciplinary artist and co-director of The Franklin in Chicago, IL. Soto holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a Bachelor’s degree from Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Diseño de Puerto Rico. More of Edra’s work can be found on her website.