Beyond the Frame: A Conversation on Latinx Family Photography with Deanna Ledezma

I first came across Deanna Ledezma’s work in Art Journal in 2021. Her essay “Regarding Family Photography in Contemporary Latinx Photography” extended an invitation for reframing our reading of Latinx images. Ledezma’s work reflects on Marianne Hirsch’s conceptualization of the affiliative look in order to complicate how a Latinx family photo’s personal value and political potency can be made vulnerable when it becomes a public site onto which “desires and difference, longing and fear” can be projected. Referencing Latinx artists who infuse familial imagery into their own work, Ledezma contends making private family photographs public is sometimes a risk worth taking.

The popularization of digital archives like Djali Brown-Cepeda’s Nuevayorkinos and Guadalupe Rosales’s Veteranas and Rucas recover unsung familial histories and Latinx subcultures, the photographs generate feelings of nostalgia and connection, signaling how sorely needed and significant their undertakings are. In her own work, Ledezma reads beyond the physical frame of the photograph and past the limits of legibility—complicating how we arrive at and define family photographs. In our conversation surrounding her recently completed doctoral dissertation, I begin by asking Ledezma to discuss her manuscript which includes chapters on Chicano photographer Louis Carlos Bernal and her own Mexican immigrant family’s photographs.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Sandra Riaño (SR): Could you describe the nature of your research?

Deanna Ledezma (DL): The premise of my dissertation “The Fecundity of Family Photography: Histories, Identities, Archival Relations” is the question of “what makes a photograph a family photograph?” In exploring this idea, I seek to complicate and to productively problematize notions of family and to deconstruct the ingrained ideas we have inherited about what family looks like.

SR: How did you define family photography?

DL: Initially, I avoided the term. I was reluctant to use the term “family photography” because I had absorbed these narrow definitions of what a family photograph was and what it looked like. I was worried that my scholarship might perpetuate heteronormative ideas of family and its compulsory heterosexuality. I wasn't sure if family photography was a topic that I wanted to spend a long time researching. It turns out I do. But I had to understand the expansive potential of family before I readily embraced family photography in all of its capaciousness. Now when I use the term family photography, I always address issues of kinship and belonging alongside that term to reiterate all the generativeness of it and also to remind people that “family” is just one form of making and establishing social relations.

SR: How did you approach the materials that made their way into your dissertation?

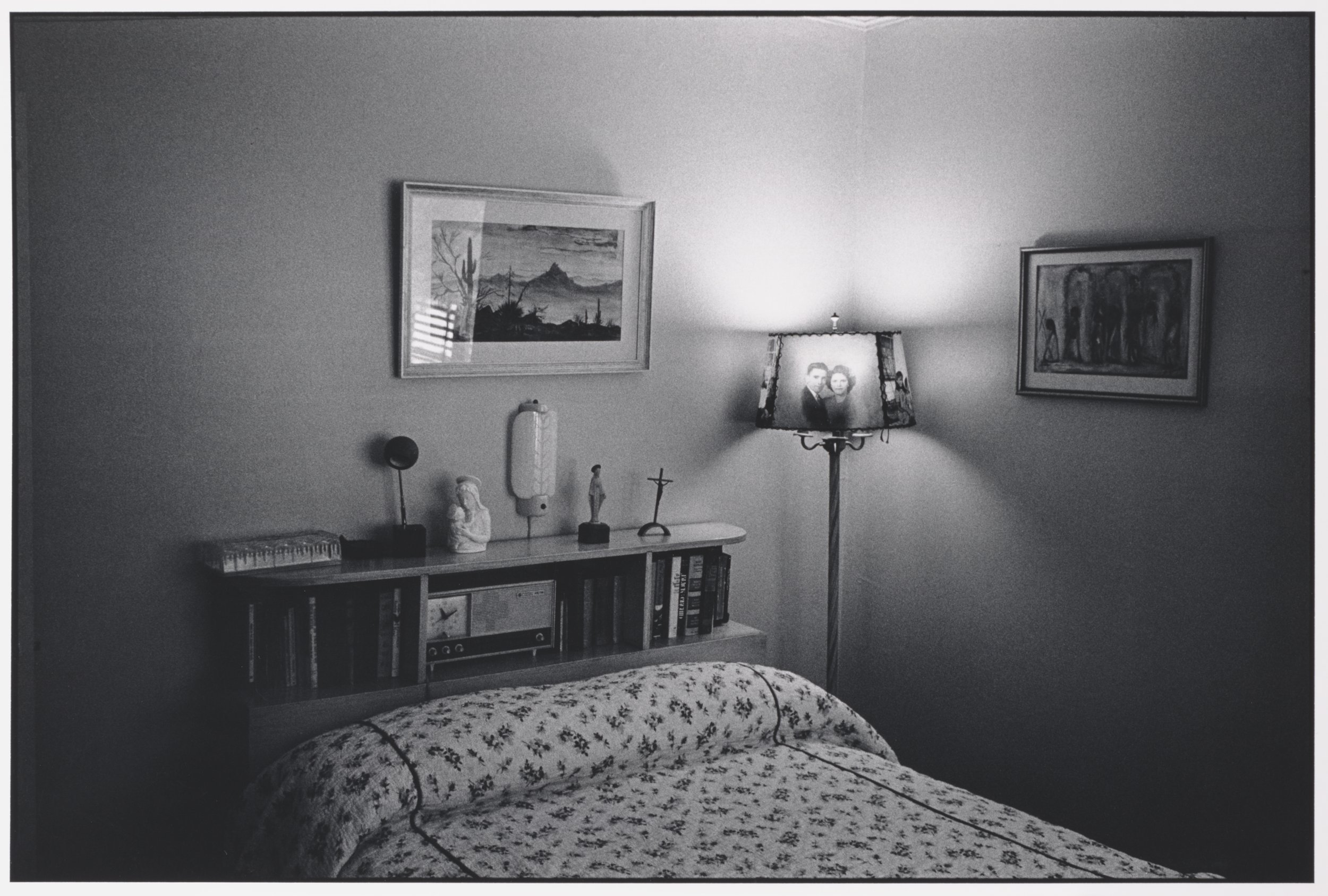

DL: A foundational decision I made early on in my dissertation was that I wanted to look at photographs of photographs or meta-archives. So, the way in which I entered each archival collection was through a photograph that depicted photographic arrangements. From the beginning, I was interested not only in the emotional connections people had to family photographs and the ways in which identities were expressed through them, but also how they [the photographs] were treated materially. I wanted to examine the ways in which people have talked about various groups’ relationships to photographic objects, whether that's the ofrenda, the altar, or the fireplace mantel. What ended up happening was that I had to look beyond the frame of the photograph, and beyond even the walls of the practitioner’s home, to understand what was being expressed, what was being resisted, what was being upheld, through photographic arrangements. I wanted to learn as much as possible about the contexts in which the photographs were made and circulated and to reinstate the lives of the practitioners and the makers of these objects.

“I had to understand the expansive potential of family before I readily embraced family photography in all of its capaciousness”

I owe so much of this approach to bell hooks’s essay “In Our Glory Photography and Black Life.” In it, she talks about her grandmother's photographic arrangements as being walls of resistance and the importance of those photographs in a racist and white supremacist society. For many people, the idea of walls lined with photographs resonates with their personal experiences, but bell hooks’s essay makes clear what the stakes were [and are] for minoritized groups and people of color. Family photography, and the display of family photographs, cannot be universalized. To do so would flatten meaningful differences in those practices.

SR: Speaking of walls of resistance, one of the images that circulated around your dissertation defense, made by Chicano photographer Louis Carlos Bernal, depicts a similar photographic arrangement. What realizations did you have surrounding family photography when you were writing that chapter of your dissertation?

DL: Yes, his portrait of Elina Laos Sayre from Images and Conversations: Mexican Americans Recall a Southwestern Past (made with Patricia Preciado Martin). As I said earlier, my entry point for all of my chapter subjects was photographs of photographs. The portrait of Elina Laos Sayre that circulated for my dissertation defense is the most photographically saturated portrait in the book. Images and Conversations is not the first place most people go when they think about Bernal’s photographs because he's so renowned for his color photography. I'm inviting viewers and readers of Images and Conversations to think about this book as a kind of collective family album. For those of us who don’t have multigenerational experiences in the United States, this is an invitation to consider the effects of settler colonialism and of gentrification, to heed the warnings that some of these [narradores of the book] make. The argument is for us to think beyond the biological family and to look at these photographs as something representative of a collective Latinx identity and, at the same time, to remain cognizant of the distinct identities and experiences that make up Latinxs.

SR: What are the stakes you’ve identified in your work?

DL: One of the major stakes of my research is that Latinxs cannot be treated as a monolith. I want to look at the particularities of Latinx identities and understand forms of identification that predated Latinx or even Chicano, for that matter. I want to understand what motivated people of Latin American descent to use the terms that they did in the places that they lived. Photography is interrelated to the second facet of this goal: to destabilize monoliths of Latinx families because so much of how we understand family is through photography and other visual representations. The issue of Latinx monoliths is also important because of the ways in which Latinx families have been politicized, namely by prioritizing the nuclear family, sometimes for very reasonable purposes, such as keeping migrant and mixed-status families together. But this emphasis on the nuclear family has sometimes been at the expense of queer and non-binary people–really anybody who doesn’t adhere to compulsory ideas of heterosexuality.

SR: How do you approach reading photographs?

DL: My understanding of how we experience photographs, for better or worse, was shaped by Roland Barthes’s book Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. His conceptualizations of punctum and studium were liberating, in terms of validating emotional engagement with photographs, but I soon learned that this same mode of experiencing images could be used to suppress the histories, experiences, and emotions of others. There is a notorious example which several scholars, including Shawn Michelle Smith and Margaret Olin, have pointed out, in which he becomes so fixated on a detail of a photograph that not only does he misremember that the detail (it's a necklace), he also becomes more interested in his own experiences, his own feelings, and those of his family, rather than those of the Black subjects of James Van der Zee’s photograph. I say all of that, because this tension between studium and punctum is something to be aware of: studium being the kind of cultural and historical information in a photograph; punctum being the thing that is unforeseeable, the thing Barthes would say “wounds” us. It's the kind of detail that makes something go off emotionally within us. So even as I might look at a detail and feel something, I always try to pull back from it because I know the kind of damage that punctum can do.

SR: What do we lose when we only read photographs emotionally, or lean into punctum as Barthes describes it?

DL: We risk losing the historical context and the particularities of those people's experiences. Of course, there are limitations to what kind of information a photograph affords us, so it's no surprise that we would have such a strong response to the visual content. As a historian, I feel that it's my responsibility to provide that contextualization. But, I will say that, as a person who looks at images, I am not immune to emotional responses. Those can be very powerful signals of how we're relating to them, why they have some importance to us, and why they have gained our attention.

We also risk supplanting the experiences of others with our own. In my Art Journal essay “Regarding Family Photography in Contemporary Latinx Art,” I am responding to Shawn Michelle Smith's “Feeling Family Photography: A Cautionary Note,” in which she discusses Marianne Hirsch's conceptualization of the “affiliative look,” or an intimacy one feels when looking at a family photograph that is not their own. Shawn, my dissertation committee member, posed this problem to me early on in my research, and I interpreted her “Cautionary Note” as a moment not just to reflect upon how problematic the affiliative look is, but also what it means more specifically, when we're looking at photographs of Latinx people in a U.S. context.

SR: Your essay in Art Journal prompted me to reflect on my own experience following the New York City Latinx digital archive Nuevayorkinos. In the absence of my own family photographs, Nuevayorkinos generated the possibility of connection through a shared cultural history vis-á-vis family photos. What role do digital archives serve in history and memory building?

DL: I think that these projects, as collective archives, demonstrate which forms of storytelling, “historical artifacts,” and voices are considered valid. They produce counter-representations and counter-archives to the things that have been considered “knowledge” by institutions that have largely excluded these minoritized groups, whether on the basis of race, ethnicity, class, gender, or sexuality. I'm paraphrasing scholar Maria Cotera here, when I say that what is left out of archives is equally as significant as what is in them. These kinds of initiatives, these collective archives, are also a way for us to assess and critique what has been conventionally included in traditional archives, as well as who has been able to access them.

“Defining a family photograph shouldn’t be based upon image content alone, the events it depicts, who made it, or even who has kept it.”

SR: If someone came up to you today and asked you to define what a family photograph was, how might you respond?

DL: Defining whether something is a family photograph is partially based upon the person looking at a photograph; it is a subjective experience. When thinking about all the possibilities of what a family photograph is, I ultimately want to leave room for alternative forms of belonging, of kinship, of claiming histories, of knowing. I want to leave room for the chosen families, the fictive kin, the equally important arrangements that constitute family. There are many factors that prohibit us from either having family photographs or feeling that we belong to any narrow definition of family. The idea that we all have a surplus of family photographs to draw upon is untrue. For many people, it is a kind of privilege. By necessity, that definition must be open. Defining a family photograph shouldn’t be based upon image content alone, the events it depicts, who made it, or even who has kept it.

SR: In the past year, it feels like Latinx photography has had a lot of visibility: we had Ferrer’s groundbreaking book, Aperture's first Latinx issue, the Mellon Foundation’s $5 million grant to support the work of Latinx artists [the Latinx Artist Fellowship administered by the U.S. Latinx Forum]. What has it felt like to come to the end of your dissertation on the precipice of all of this?

DL: Yes, and I would add the Henry Luce Foundation’s funding of the Louis Carlos Bernal exhibition, which Ferrer is curating at the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography. It’s been affirming to see Latinx photography getting long overdue attention. The next stage is to be constructively critical of the ways in which Latinxs and Latinx families have been visualized through photography. I have been working through these issues through my research and writing, especially with my forthcoming essay on Diana Solís’s photographs of Mexican American communities in Chicago. These recent exhibitions and publications are a major stepping stone toward more diverse and inclusive coverage of Latinx photography and Latinx families and kinship making.

Image Credits:

Recamara de Mis Padres/My Parents’ Bedroom, 1980. Photograph by Louis Carlos Bernal. Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal.

Untitled, 1980. Photograph by Louis Carlos Bernal. Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal

Photograph by Deanna Ledezma, 2022

Photograph by Deanna Ledezma, 2022

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal for allowing us to reproduce their father’s photographs.

Sandra Riaño is a photographer and historian. She is the founder and curator of the contemporary Latinx photography newsletter Mira. Sandra’s work reinstates the contributions of Latinx photographers within the U.S. photography art canon. She is interested in tracking both the work of contemporary Latinx photographers and thinking about the materiality of photographs as objects, artifacts, and counter histories. Her work can be seen in Womanly Mag, Latino USA, and Wellesley Magazine. Sandra is a graduate of Wellesley College where she received her B.A. in History and currently lives in New York where she was raised.

Deanna Ledezma is a Lecturer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She earned her Ph.D. in Art History from the University of Illinois Chicago in 2022. During her doctoral studies, she was the Research Assistant for the Inter-University Program for Latino Research/Mellon Program. Her essays have been published by Art Journal, Photography & Culture, Walls Divide Press, and Green Lantern Press. In addition to her research-based scholarship, she also collaborates with artists and writes non-fiction based on her family’s experiences as Mexican immigrants in the Texas Hill Country. Her forthcoming essays include “Dismantling Latinx Monoliths: Representations of Material Culture, Communities, and Kinship in 1980s Chicago” in The Routledge Handbook of American Material Culture Studies and “Photographs from the Fields: The Digital Activism of the United Farm Workers” in the Re:Working Labor book (2022). She also wrote the foreword to Diana Solís’s artist’s book Luz: Seeing the Space Between Us, debuting this July.