Survival Stories through Portrait Painting: A Conversation with Alicia Brown

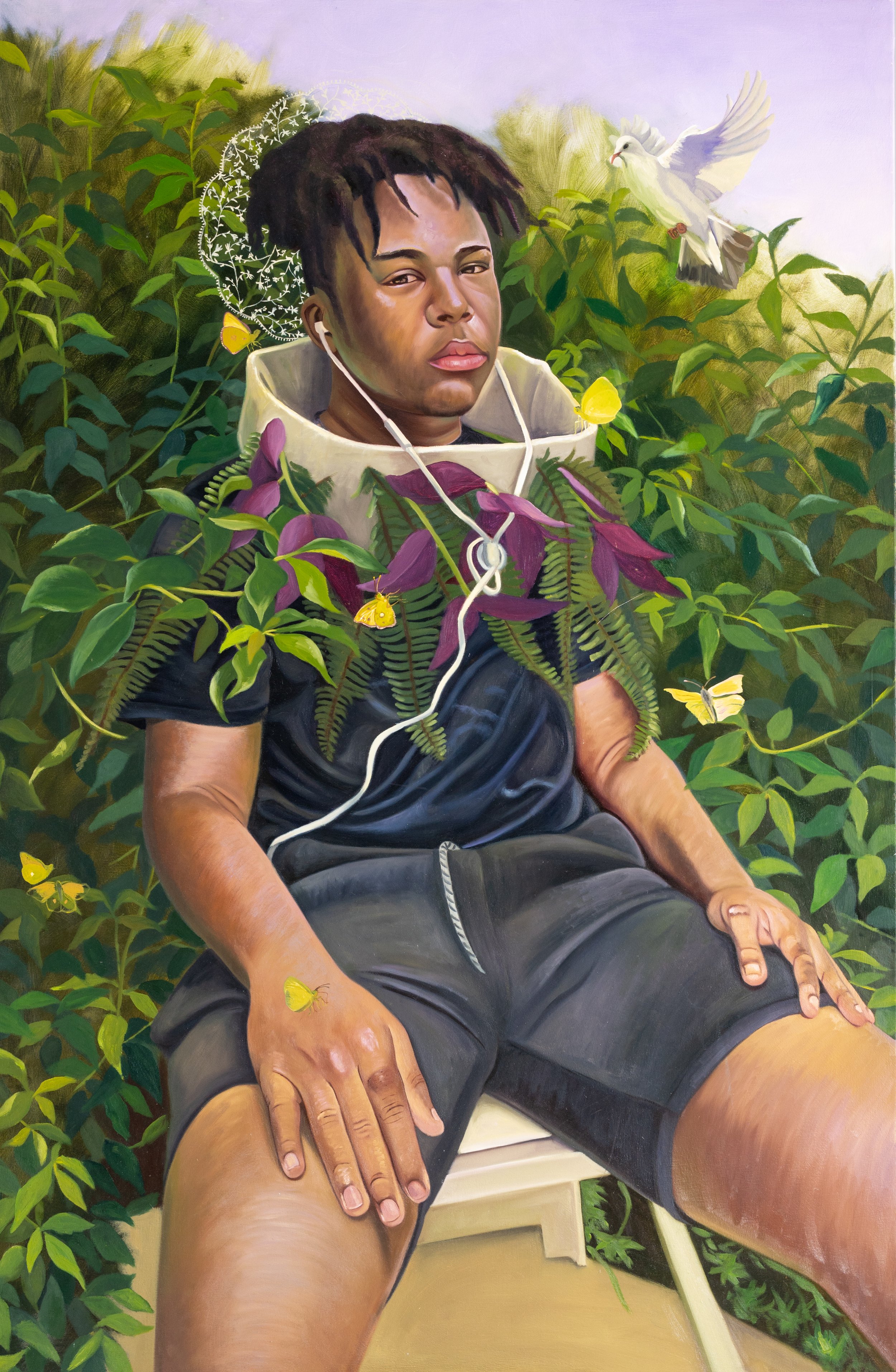

Alicia Brown is a contemporary figurative artist who uses traditional painting techniques and symbolic references to examine issues of race, power, and social status. A native of Jamaica, Brown is a graduate of the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, and the New York Academy of Art where she received her MFA. After teaching for a number of years in Jamaica, the artist eventually migrated to the U.S., where she now lives, in Florida. Brown's oil paintings and drawings feature portraits of young black subjects surrounded by lushly rendered foliage. Her sitters, while casually dressed, often appear adorned with collars of paper doilies, balloons, or ferns to reference the European ruff collars that became popular during the 16th century––a period which heightened the development of the slave trade to the Americas. The collars, like other features of her work, are part of a symbolic vocabulary that considers the continued legacy of the colonial experience on contemporary life, cultural mimicry and adaptation, and the burdens and beauty of tropicality. Many of the paintings in Brown’s recent solo exhibition at the UUU Art Collective in Rochester, New York have an air of playfulness different from her previous works. Last year was a period of deep sadness for the artist. She had to deal with the death of a relative and another's mental health crisis in the summer of 2021. In these images, context and content, like past and present, collapse. Like the surface of her paintings, the veneers of beauty, status, and identity are often created and performed under conditions of violence.

In February 2022 I sat down with the artist to discuss her work.

Petrina Dacres: In your wall installations of drawings and paintings at the Clemente Art Center in 2021 you included close-up images of plants and animals as well as portraits. Your solo show this year in Rochester, NY had full length portraits of young people surrounded by nature or adorned with plant life. Perhaps we could start by discussing this combined interest in portraiture and nature.

Alicia Brown: I'm interested in nature because we are a part of nature. I grew up in rural Jamaica in the mountains and I was always surrounded by nature. When you go away from that space you start to miss it; you start to realize that the air smells differently. You miss seeing a flower and hummingbirds and grass growing instead of just looking at concrete every day. Humans have become so far removed from nature. In the paintings, if I force the figures into these natural neck pieces and natural environments, it’s because I want to bring across the idea that nature is healing and we need it.

I was also looking at how insects and plants use mimicry as a way of surviving and adapting to a given space. I'm trying to compare that to how humans use mimicry to adapt to a space as well. We are not different from nature in that regard. Through nature—and through my images of plants and animals—I am interested in the idea of survival. When you move from one place to another you're trying to find elements of things that look familiar, like your home. For me, when I moved to the United States, I would get so excited if I saw a plant that looked similar to a plant from back home. These are the elements of nature that we use to survive even if it might not be in a very obvious way. I'm still invested in doing more research about how the natural elements influence the way we do things, especially in fashion and design.

PD: You seem to take pleasure in depicting fabric and fashion. Could you discuss your interest in fashion and your approach to depicting ornamentation in your paintings?

AB: In Jamaican culture, people love to get dressed up for any occasion. When you dress up, it actually changes how you feel about yourself and it transforms you. I like the idea of fabric because it is a way of transforming the wearer––to add a different self, for want of a better word. It's almost as if you're recreating who you are every time you dress a certain way. It's also about fitting in. It's about acceptance. Stuart Hall wrote about identity as something that is not fixed but that it is an ongoing process––it's a performance. This is what I was trying to explore in my paintings. I like this idea of a performance.

If I could go all the way back to when I first started making these paintings of [black] women dressed in ruff collars, that was maybe 2012 or 2013. This was before I decided to go to the Academy in New York and I was still in Jamaica. I loved the streets of downtown Kingston for various reasons and one of the things that always jumped out to me is how expressive people are, especially on the streets. People are not afraid to express themselves, and they will do it in whatever way just to get that attention because it does something for them. I am sure you're familiar with the sidewalk street salons in downtown Kingston. That's where I started to look at my culture more intensely. What was fascinating was to see these women fixing someone's hair, but what really caught my attention was the way they adorned themselves, the way they dressed elegantly. They would wear these pearl necklaces as if they were stepping out of a scene from a movie set in the 17th century. I was always fascinated by that period and I still am. I thought to myself how interesting it would be to mix these different cultures in my paintings.

PD: Yes. In many of your paintings your subjects are dressed in contemporary casual clothing, but you have adorned them with your own version of 16th and 17th century dress codes—necklaces of sweets and toys, ruff and headdresses made of an assortment of materials including foliage, balloons, and insects.

AB: The juxtaposition of objects makes the narrative of the paintings seem bigger than just my representation of something from one culture. When you see a ruff collar you start thinking about 16th and 17th century aristocrats. So I started to think about how I could create my own collars and give meaning to them. I'm always trying to figure out how I can use them in a way that is mine.

The first time I saw a painting with the ruff collar was in Dutch paintings. The nature of 17th century Dutch paintings is that normally the background is darker and then you have this white collar to create that strong contrast. That was alluring to me. What really drew me into that type of painting is that even though there's this powerful person in the image, it's not the person that really creates the power but it's the object that we relate to. I thought that was striking. The thing becomes even more powerful than the person who is represented because our eyes are immediately drawn to these objects. When I started making my paintings, I focused on this aspect of the power and politics of objects.

PD: In some of your paintings the figures seem burdened by the collar. In the painting Male Bird of Paradise, for instance, his body appears weighted down by his floral collar.

AB: When you mention that, I get emotional because my nephew depicted in the painting was going through a lot mentally and he is burdened, of course. The collars may look beautiful with the plants but it becomes a burden. Can you imagine even wearing one of these 16th century costumes? These collars were originally made from wires and beads. Can you imagine wearing that around your neck for long periods of time? It becomes a burden on the body in that sense. And, if you don't wear it, then you'll lose that kind of visual power and control as a ruler or as a person of certain class or status.

In Male Bird of Paradise I created that collar from cardboard and paper, and then I attached leaves and ferns. It's not that the collar was heavy. The object itself was not heavy. It wasn't an object that was his burden but rather, his emotions were overwhelming. I wanted to make the collar out of a range of natural elements because I want it to be a shield or a kind of support. It has multiple meanings.

PD: Your treatment of dress and adornment in your paintings weaves together ideas of cultural and design creativity, mimicry, and identity which makes the paintings conceptually complex.

AB: Personally, I'm not really into fashion that much, but I'm fascinated by how people express themselves through clothing and use fashion to fit in and show a certain status. When I'm making the paintings I'm not even thinking about fashion, in that sense, but, when I look at the paintings, I am thinking of how I can make the image rich. One way is by just layering things that you wouldn't think belong in the same space. But, I do take elements from these periods like the Elizabethan era with these elaborate dress codes of kings and queens. It's about enriching the image that you're looking at. I am not necessarily elevating the status of the figures by painting these references. I'm not trying to do that.

PD: So particular codes of adornment are also used as formal or symbolic strategies to enrich the surface of the paintings for the eye of the viewer?

AB: Portrait of Lady Cameal from Alva is a painting of my sister. It is based on a photograph I took of her in which she is wearing jeans and a t-shirt. In making the painting, I wanted her to feel like a queen. So I added beads and pearls to the clothing she wears in the painting. Then I created the collar from paper doilies that I bought which I'm kind of obsessed with.

PD: It's hard to not make comparisons between the black subjects and the clothing references that you use to adorn them. The clothing was worn by Europeans during the height of the slave trade. They seem to create a narrative around the legacy of colonialism.

AB: We're from the Caribbean. I love history. And one of the things I thought was lacking in history is that I didn't know enough about our African descendants. I use these elements to reflect on their experiences. What I find fascinating is that histories are written by individuals and that you can always change them. That's what I'm trying to do—share my own idea of that same story. To add-on to the stories [of black people in the West].

PD: When we discuss how Black people adorn themselves with aspects of European culture it is easy to take a critical position against that type of practice. When you discuss the issue of cultural mimicry you also talk about adaptation. I find that your position has a certain kindness and understanding of decisions people make to survive under conditions of power and extreme violence.

AB: My move to Kingston is actually how it started. When you grow up in a certain space, you only know what is in that space and I didn't have access to TV. Growing up, I didn't have access to a lot of things. My access was through books––I was reading about different issues in different cultures. If you're from the rural areas in Jamaica everybody says “Kingston is a bad place” and expresses negative ideas about it. But when I moved there I started to see how rich Kingston was through the diversity. It made me question and become more critical about my own perceptions. My move to Kingston was important in developing a critical perspective on knowledge and identity.

PD: Alicia, could you discuss the inspiration for your recent exhibition, What About the Men?

AB: The idea for What About the Men came about from observing my nephews. I have no brothers and I don't have a very close relationship with my father, even though we have a relationship. By observing my nephews, having my son, and looking at how men operate in this society, I realize that the media and different cultures tell men to behave a certain way.

PD: Admittedly, I was surprised by and curious about the exhibition’s title. I remember several years ago this question was being asked in Jamaica by men who were concerned that girls were outperforming boys in education, with more young women at university, and of course there were also concerns about young boys getting mixed up in crime. I remember feeling that the question was being asked without acknowledging the serious institutional and cultural biases that existed against women. And of course, today, following the renewed conversation around gender discrimination and sexual violence with the #MeToo movement, the title is provocative. Is the title a confrontational question or a beckoning to conversation? Could you discuss the title's significance?

AB: Before I started that new body of work, I was just making the paintings that I am most known for—these portraits of women—and I had to put them aside because when something is pressing it's very hard for you to focus on doing anything else. I had an invitation to this solo show at UUU Art Collective in Rochester, New York, and at the time a lot of things were happening in my family. This is not easy for me to talk about. One of my nephews was having a lot of issues. He just came out of the hospital after being “Baker Acted” and this wasn't the first attempt.

PD: Could you explain what this means?

AB: It's a term to describe putting someone in an institution—a behavioral or psych ward—if you are trying to hurt yourself or commit suicide. You're under watch 24 hours to determine the reason behind wanting to self-harm.

PD: I see.

AB: The painting in the show, Male Bird of Paradise, depicts his aura and the way he looked when he came out of the hospital. We wanted him to come and stay with us to get a break and to be in a different environment. He has tried numerous times. That along with observing other nephews, you know, I could not focus on anything else. I was trying to figure out how I can help them, how I can help my nephew, in particular. And, I started thinking about my son as well and thinking about how cruel society can be, how cruel family can be and how all of that affects you.

As an artist, as a mother myself, and as his aunt, I love him dearly. I started to think about how I could bring up this idea of mental illness, especially the fact that young men feel like they cannot talk about their emotions or talk about what hurts them.

PD: Another painting in the show, You Look Just Like Your Father, includes female figures in a double portrait.

AB: That's the only painting in the recent exhibition depicting women. That painting is about my niece who I took care of and who was like my child––we had this very strong connection. I decided to include the painting in the exhibition because her father was not a part of her life, and I could see how that affected her. It's a very common thing in Caribbean culture where you have a lot of absent fathers. Or, a lot of fathers who have about a hundred children, and you know it's almost impossible for you to maintain a relationship with a hundred children. In my niece's case, she was her father’s only child and he decided he didn't want to be a part of her life, and that really hurt her.

PD: So this work is also about manhood and pain from a different perspective––from a daughter's perspective.

AB: My niece's father recently passed away. He was killed. She was hoping to have this relationship, but then he got killed. So you can just imagine how that affects someone because she loved her father. She looks just like him, and that is why I decided to name the painting that too.

The painting is of my niece and her friend. I needed to represent both of them because they are two strong young women. I wanted to represent them in a way where they feel like they belong somewhere and that their stories are as important as anybody else's. I wanted to represent the women, along with young men, to show how women are expected to hold up the fort in a lot of ways.

PD: In the background of the painting there's a faceless male figure on the wall. Is this to represent an absent father?

AB: I almost forgot that was there. Interestingly, that's a silhouette of my father. Even though he's my niece's grandfather there's still not a strong bond between them. So again, I am pointing to that cycle. Your father can be present but can also be absent. You're not really communicating. I really have no relationship with him. And that's also the case for my nephew, who as I said, inspired this whole series of paintings.

PD: You have said that you wanted viewers to see themselves in the sitters: “to share their world, and to come to the awareness that we share so much in common, we are connected as beings.” How would you say this relates to your approach to contemporary figuration?

AB: When a viewer looks at one of my paintings, I want them to see that they are no different from the person they're looking at in the painting, because as humans, we have a certain connection. In making the paintings, I'm trying to understand the different stories I have heard and the histories I have learned. I'm trying to figure things out. As an artist, I just try to share the stories [of] these experiences that I've had and [the] experiences of others. I also want the viewers to keep questioning as well. When they look at a painting, I don't want them to simply ask, 'Why did I put a spoon there?' but to dive deeper and try to think about the significance of the object, and what it could mean to a different group of people.

PD: What are you working on now?

AB: Currently I am working on a new body of work for a solo show with Winston Wachter Fine Art in NY scheduled for 2023.

PD: I wish you well, Alicia. Thank you.

AB: Thank you.

Petrina Dacres is a current curatorial fellow at the International Studio and Curatorial Program. As the Head of Art History at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts her teaching, research, and writing focuses on Caribbean Art, African Diaspora Art, Public Sculpture, and Memorials and Memory Studies. She is also a founding member of Tide Rising Art Projects, an organization created to support and promote contemporary Caribbean art and film.