Self Help Graphics at 50: An Interview with Karen Mary Davalos and Tatiana Reinoza

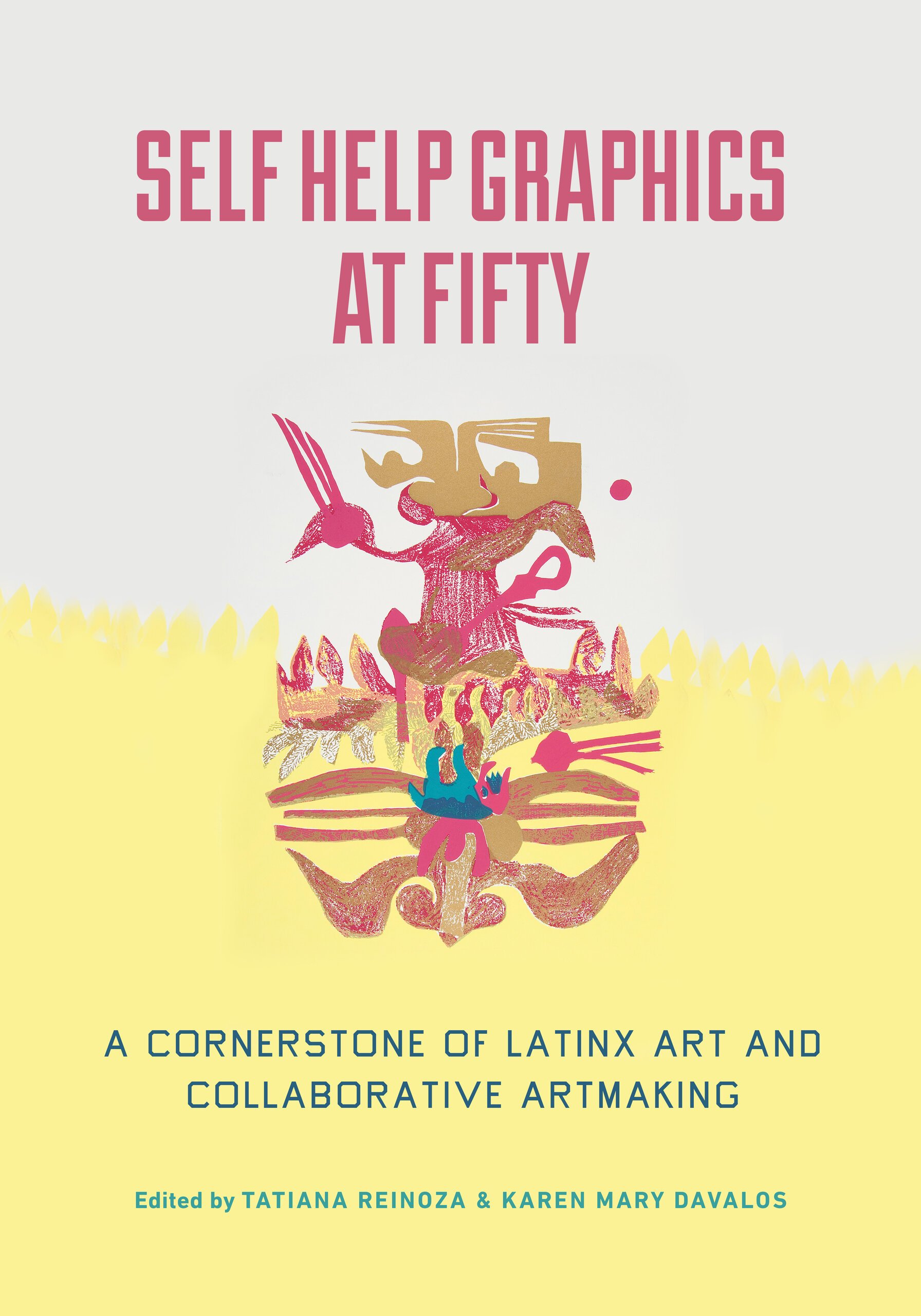

To commemorate the recent release of Self Help Graphics at 50: A Cornerstone of Latinx Art and Collaborative Artmaking (University of California Press), we spoke with editors Tatiana Reinoza and Karen Mary Davalos about their “definitive history of a cherished East Los Angeles institution over five decades of art making and community building.” See the full interview below.

—

As one of the most important legacy art organizations in Chicano/a/x and Latinx art, there's much we know and don't know about Self Help Graphics (SHG). Can you share some key takeaway lessons of the book that you'd like readers to understand about SHG’s history.

Karen Mary Davalos (KMD): There are three important lessons from the book:

1) SHG has always been an inclusive arts organization. While centering Chicana/o/x artists, SHG was inviting and collaborating with Central American, African American, Asian American and Euro-American artists. By the late 1980s, SHG had a global audience with exhibitions in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. It was and is a transnational arts organization. Paradoxically for an inclusive strategy, SHG worked within the confines of heteropatriarchy. Women and queer artists were foundational to SHG, but their voices, their art, and their subjectivities were not consistently heard and acknowledged. The co-founders, Carlos Bueno and Antonio Ibañez, were gay Mexican migrants.

2) SHG blended art and commerce, and it intervened against the expected binary of art for art's sake and political art by insisting on aesthetics and message, compelling visual techniques and social justice.

3) As Kency Cornejo suggests in her contribution to the anthology, SHG challenges the narrative of neoliberal multiculturalism by fostering “radical compassion, rather than declaring semblance,” a generative framework for exploring collaboration at SHG and beyond.

SHG has been at the vanguard of creating audiences, markets and supporters for Chicano art. Can you describe how lessons from SHG translate or can help Latinx art stakeholders to advance and promote the work of Latinx artists?

Tatiana Reinoza (TR): As you will note from the interview with Arlene Dávila in the book, as well as other essays, Self Help Graphics takes a multi-pronged approach to advancing the work of Latinx artists. First, they invest as a publisher, creating professional printmaking residencies that yield fine art limited editions. Second, through exhibitions and sales they advance the careers of countless artists who are often left out of the gallery system. Third, they nurture an art market for middle class collectors of color, and these collectors are eventually positioned to gift the work to art museums creating a sustainable cultural ecosystem that ensures longevity. We have a perfect example in the recent donation of 5,000 objects from Gilberto Cárdenas and Dolores García to the Blanton Museum. Cárdenas was one of the first patrons of Self Help Graphics and worked closely with Sister Karen Boccalero.

KMD: As I suggest, SHG has lessons for other Latinx arts organizations. I will not pretend that everything done at SHG can be effectively duplicated outside of Southern California because context is everything. However, the model of equity is essential. Screenprint Atelier, the professional print program in which artists collaborate with a master printer to create new work, is designed for equity. SHG will split each edition between the artist and the organization so that the artist receives half the edition and SHG gets the other half. The organization uses this inventory as a source of revenue to continue and expand programming. SHG also formalizes the sales from works featured in the gallery to benefit artists: 60/40 or 50/50 cuts. Another factor of success is centering artists: programming is informed by artists' needs, artists' interest, and artists' questions about the market and the creative process. Finally, the intergenerational model is effective. It builds the future generations while valuing the more established and seasoned artists. We make our own history by connecting youth to elders, elders to youth. This is a challenge for most arts organizations because of the high stakes involved with service through education, but SHG has found and enhanced programs that support both the novice and the professional, and these programs create conversation across generations.

Can you describe the collaborative ethos of SHG and why collaboration may be more essential than ever as a response to neoliberalization of the art world and markets?

KMD: I want to acknowledge Kency Cornejo for coining the term "radical compassion." She provides a phrase that captures the type of cross-ethnic, cross-racial solidarity that is not tied to sameness. The Chicana artists who traveled to Central America in the 1980s recognized as soon as they arrived in Nicaragua that they had little cultural commonalities with their hosts, but they also recognized similar political orientations, particularly a critique of US intervention in Latin America. This expansiveness cuts against neoliberal multiculturalism that tells us we need shared experiences, shared histories, shared culture to know and acknowledge each other. Difference can generate solidarity, and it can do so without flattening or insisting upon an unstated norm for whiteness, heterosexuality, Christianity, or middle class success.

My research has turned to the geographic, aesthetic, and generational differences among Mexican American artists since 1848, the year we were designated as US citizens with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. With Constance Cortez (UTRGV), I have created a search tool that united geographically dispersed collections of Mexican American art since 1848, but we do not try to define "Mexican American" nor "art"—this is a deliberate strategy to acknowledge that our current research cannot tell us enough about the historical, spatial, and aesthetic diversity of the art attributed to Mexican America. We are hoping that the search tool can eventually provide some answers about trends over time, regional patterns, and aesthetic differences. For example, our current research in Chicana/o/x art history and exhibition disproportionately favors contemporary Chicano and some Chicana artists from CAlifornia. I have contributed to this bias. One impact of this privileging is that CA aesthetics are theorized as the only paradigms for analysis. But I suspect that each region and for each time period, artists have engaged with broad and yet unrecognized aesthetics, various approaches to art-making and to visuality. I am taking the ethos of radical compassion to my research in the hopes that I can elevate the complexity and diversity of Mexican American art beyond the contemporary expressions coming from California. But don't get me wrong, we still need 100 new books about California artists, as we have not yet saturated the intellectual market. When we have parity with the top European American artists—who have 1000s of essays written about them—then we can put on the brakes, but we have so far to go.

TR: The collaborative ethos of SHG is felt in every aspect from leadership and governance to art production and public programming. The neoliberalization of the art world has led to abuses and imbalances. We see that in the movement to create new labor unions for cultural workers, to be transparent about the disparities of salaries, wages, and lack of benefits, and to fight against the willful neglect of white mainstream institutions to collect the work of artists of color. Neoliberalization is a market scheme that requires hierarchy, competition, and veiled decision making. These are things that SHG has actively worked against as a non-hierarchical artist centered institution.

Likewise, how does this collaborative ethos impact your research?

KMD: I think that that ethos of compassionate solidarity is similar to the questions that you're asking at The Latinx Project, that we don't need to assume some kind of cultural sameness, even a historical sameness; that we can still find ways of working together that are beyond the questions of characterizations of culture and people hood and that some of the ways we we come together are because of just a shared way of looking at the world.

TR: Five years ago, we began meeting and discussing the possibility of working on an anthology that would commemorate this momentous anniversary. The task seemed enormous. How could we convey the significance of Self Help Graphics to the history of contemporary art in the global art capital of Los Angeles? How did it expand our understanding of the collaborative press movement? Of the hundreds of resident artists, how could we narrow the list and do justice to the more than 800 limited editions produced in their printmaking studio? What were the most significant themes explored in their vast archive of works on paper, exhibitions, and art education initiatives? What were the tactics the organization employed to sustain their longevity in the face of budget cuts in the grant funding landscape and rampant art world racism? In true Self Help Graphics ethos, we decided that collaboration was key in tackling such a project and we assembled a wonderful team of scholars, through a call for papers and by invitation, which now includes our esteemed colleagues: Kency Cornejo, Arlene Dávila, JV Decemvirale, Adriana Katzew, Robb Hernández, Olga Herrera, Kendra Lyimo, Mary Thomas, and Claudia Zapata. Each one brought a different specialization and perspective which greatly enriched the project.

–

Self Help Graphics at Fifty: A Cornerstone of Latinx Art and Collaborative (2023)

Edited by Karen Mary Davalos and Tatiana Reinoza

360 pages. University of California Press. $34.95

Karen Mary Davalos is Professor of Chicano and Latino Studies at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She has published widely on Chicana/o/x art, spirituality, and museums. Among her distinctions in the field, she is the only scholar to have written two books on Chicana/o/x museums, Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (2001) and The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971-2006 (2010), the Silver Medal winner of the International Latino Book Award for Best Reference Book in English. Her research and teaching interests in Chicana feminist scholarship, spirituality, art, exhibition practices, and oral history are reflected in her book, Yolanda M. López (University of Minnesota Press, 2008), the recipient of two awards: 2010 Honorable Mention from the National Association of Chicana and Chicano Studies and 2009 Honorable Mention from International Latino Book Awards (Nonfiction, Arts–Books in English). She serves on the Board of Directors of Self Help Graphics and Art, where she is assisting in the capital campaign for this legendary Chicana/o – Latina/o arts organization. Her latest book, Chicana/o Remix: Art and Errata since the Sixties (NYU Press 2017), is informed by life history interviews with eighteen artists, a decade of ethnographic research in southern California, and archival research examining fifty years of Chicana/o art in Los Angeles since 1963. With Constance Cortez (UTRGV), she launched a post-custodial web portal, Mexican American Art since 1848, that compiles relevant collections from libraries, archives, and museums throughout the nation.

Tatiana Reinoza is an art historian who specializes in contemporary Latinx art and the history of Latinx printmakers in the United States. She received her Ph.D. in art history from The University of Texas at Austin in 2016 and is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Notre Dame. Reinoza has contributed to many scholarly publications on the history of Latinx printmaking including ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965-Now. In addition, she co-curated Hard Fought: Sam Coronado’s World War II Series at the Benson Latin American Collection and All My Ancestors: The Spiritual in Afro-Latinx Art at the Brandywine Workshop's Printed Image Gallery. She is currently a Getty Scholar, in residence at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.