Aymarana Wasapp yatiqawi (Learning Aymara on WhatsApp)

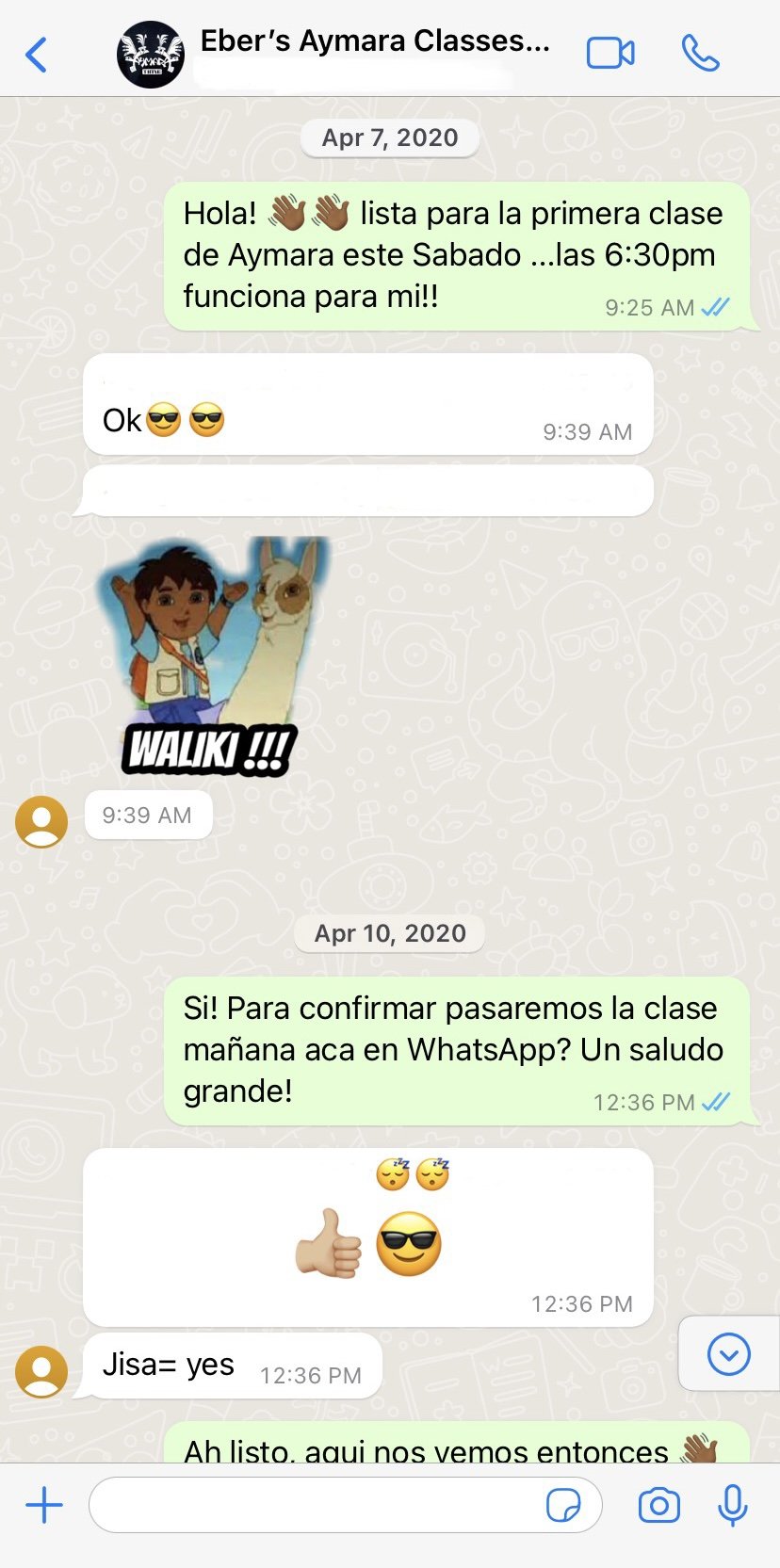

As the world seemingly fell apart at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, I found myself logging in weekly to a WhatsApp group––phone in hand and the WhatsApp web interface loaded on my laptop. Suddenly, the message notification I was waiting for pops up in the chat interface. I enter the chat and am greeted by an image of a sunrise over a field, likely in a pueblo outside of El Alto in the Bolivian highlands of La Paz.

KAMISAKI MASINAKA!!! 👋🏾

ASKI ARUMAKIPANAYA!!! 🌱

A voice note promptly follows and class has begun. An hour goes by and the chat is populated with punchy memes and GIFS sprinkled here and there with Spanish, English and Aymara. Despite the layers (and centuries) of distance and separation, here I was in the middle of the Midwest learning––remembering––Aymara, a language whose origin in my family is hazy but close enough that my grandparents were fluent speakers. Now it’s my turn. I pause in between breaths on how to pronounce the consonant ch, a familiar sound I've heard my whole life. I tap the microphone icon, start speaking and press send.

"𝐜𝐡 ___𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐚”

As someone who grew up in Queens, NY, where many versions of Spanish coexist, my Spanish vocabulary has Quechua and Aymara dispersed throughout. Most of the time, these words emerge without my knowledge. That corpus gradually grew as I partook in conversations over dinner, joined dance fraternidades in Queens, and visited the mountainous landscapes that my family originally came from. In essence, I knew where I came from but I also didn’t. On my last trip to Bolivia in 2019, my mother and her siblings took us to our grandparents’ hometown of Santiago de Callapa, an arid, quiet town that is now home to mostly Aymara-speaking elders, given increased migration sparked by socioeconomic and climate factors. It was on this trip that the unknown became a bit less blurry for me, where clues in the form of names and dates challenged spatial boundaries I’d previously never questioned. I had known that lack of access to land alongside economic opportunities such as the nationalization of Bolivia's tin mines in 1952, had prompted movement on both sides of my family.

But my maternal great-grandfather had, in fact, gradually migrated by way of Puno, Peru until eventually crossing and settling down in the border town of El Desaguadero, about 45 km from Tiwanaku, a sacred archaeological site belonging to one of the most important early Andean civilizations.

New Yorkankasktati - Estas en New York?

Reacted with a ❤️

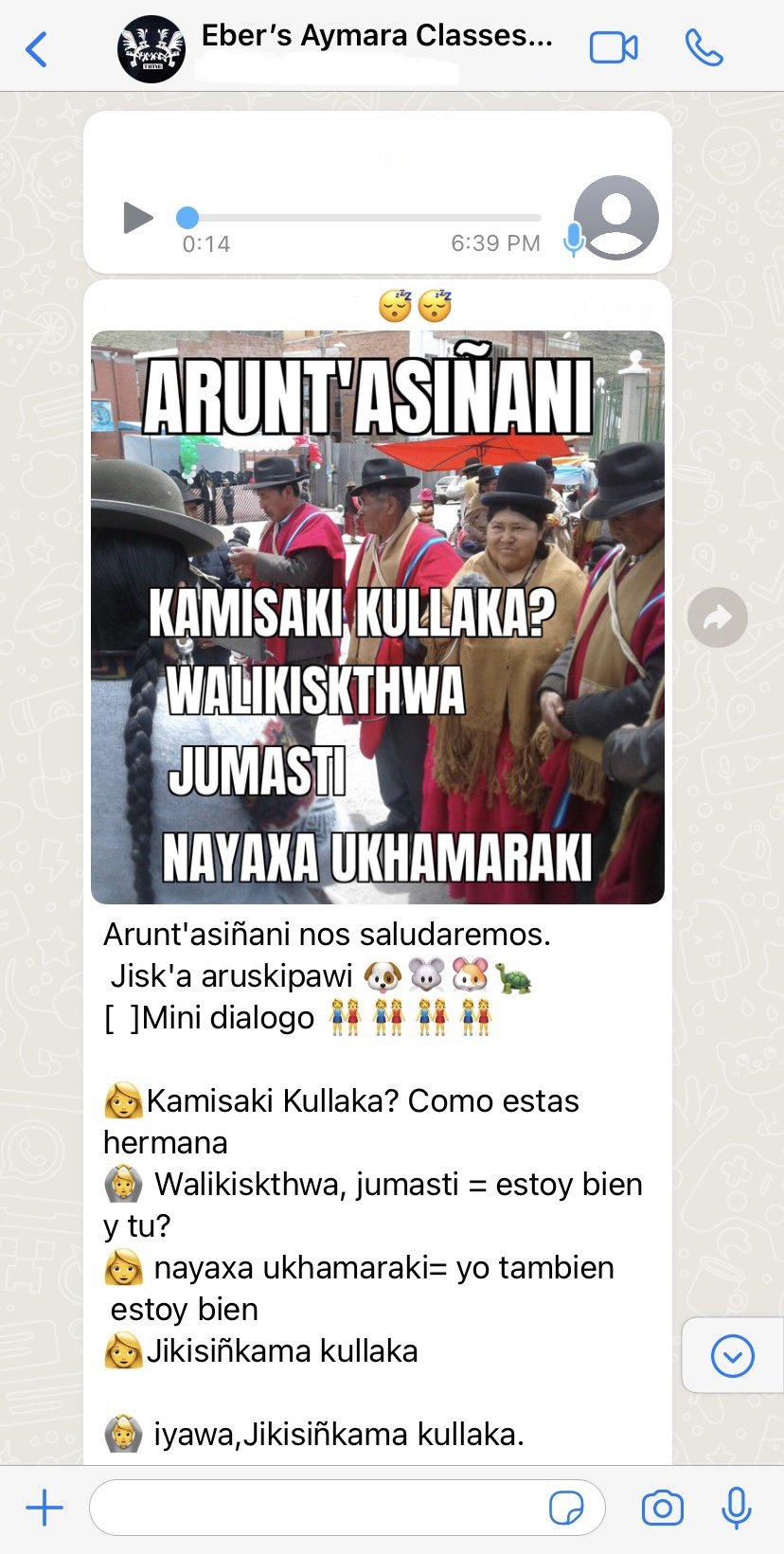

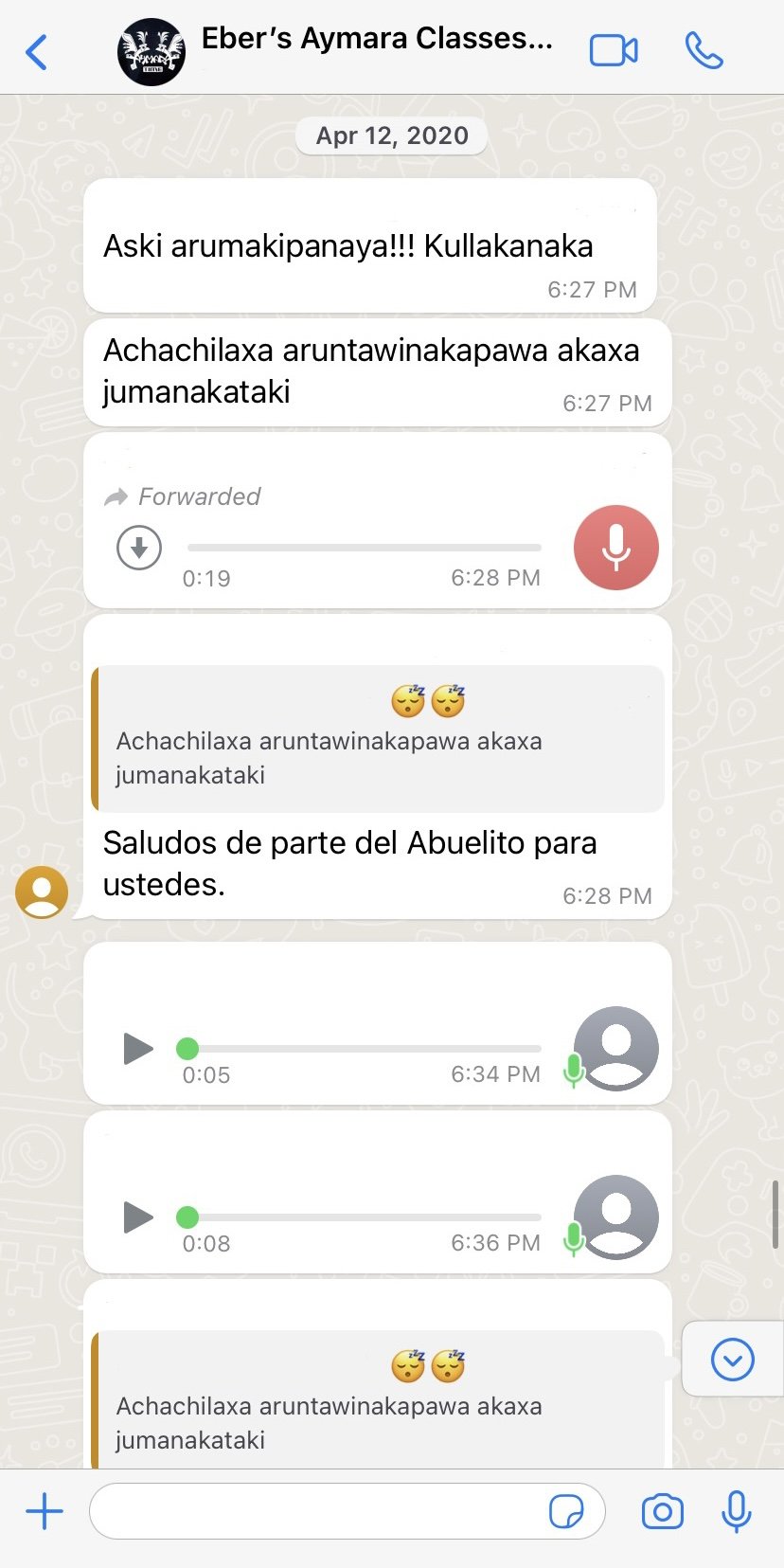

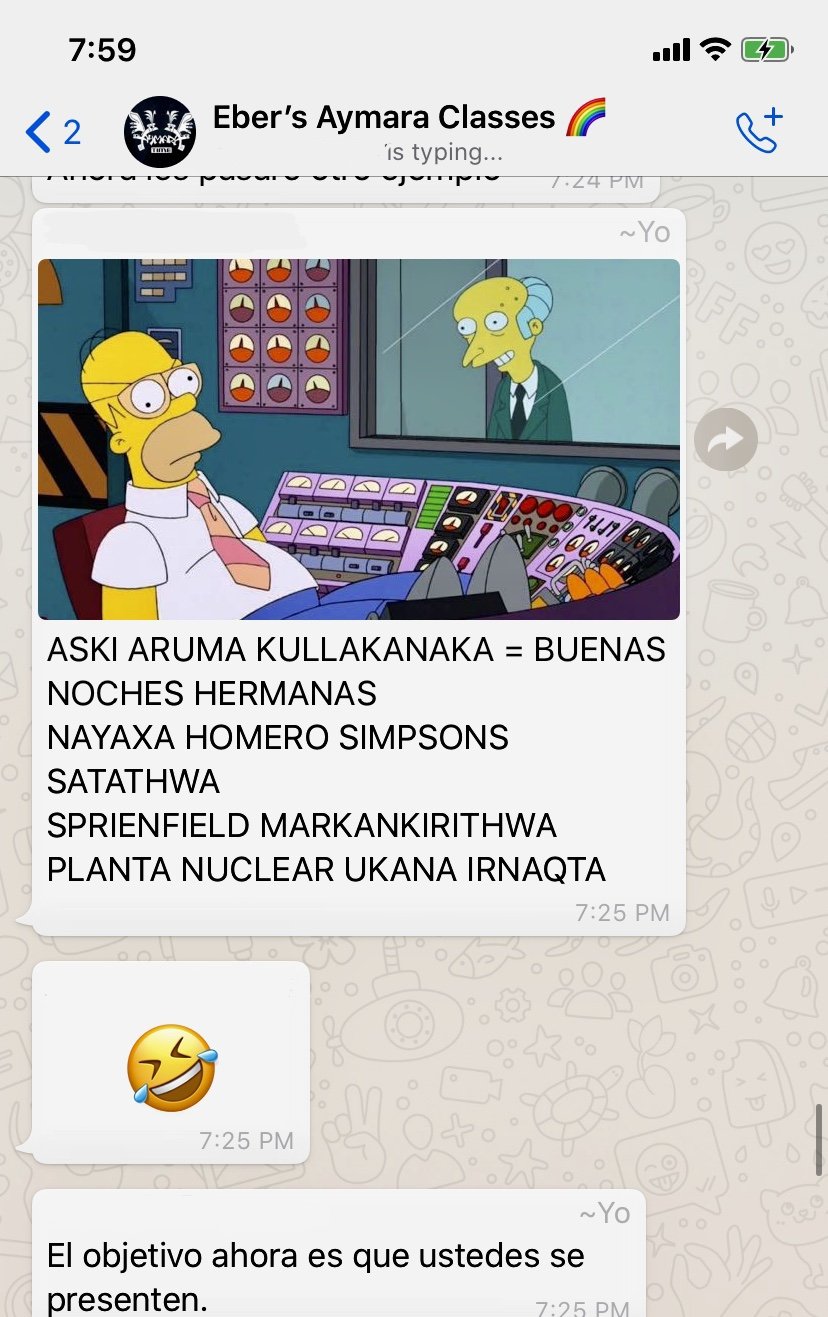

At the start of the pandemic, a friend of mine in the Metro DC area extended an invitation to join an Aymara study group for heritage learners. Our yatichiri (teacher) was Eber, a first-generation Qullan Aymara born in El Alto, a majority Indigenous city adjacent to La Paz, Bolivia’s capital. Soon enough, data from mobile phones from El Alto, Ann Arbor and Metro DC were exchanged in near-real-time using Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), a popular technology used in various chat applications. We receive a voice message with prompts based on the graphics or text that are continuously popping up in the chat. One by one, we send our answers, receive feedback and repeat in cyclical form. Audio of the yatichiri’s relatives speaking Aymara or GIFS of everyday scenes in the bustling corridors in El Alto sometimes make their way to the thread as do phrases intermingled with familiar English words. While disorienting at first, I soon realized that our lively chat held much more than memes and voice messages. It also holds identity negotiation, humor, solidarity, and a collective pain of sorts.

A small gasp dawned on all seven cousins when I told them what Tío Fidel had told me in our aunt’s kitchen. My cousin jokingly said “so, we’re part Peruvian…this shall never leave this room.” I knew this comment percolated from a cultural and nationalistic rivalry between both countries that I never really understood, given the pre-meditated obscurity of many aspects of our shared highland Indigenous cultures. Amongst scholars there is debate about the origins of Aymara, whether it originated in Peru’s central and southern sierra or on the shores of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia where the Tiwanaku empire was a stronghold. Architectural constructions and monoliths such as la Puerta del Sol may provide a gateway to better understanding the fluid nature of the complex networks that existed back then, but only if we choose to look back. On the first days of school, I would come bearing gifts for my teachers––silver-plated Puerta del Sol pen holders courtesy of my parents. This monolith structure in the form of a gateway currently stands at Tiwanaku, which most Bolivians would agree is the cultural and spiritual capital of the Aymara. Yet the Puerta del Sol found on my pen holder stood as a backdrop to the national coat of arms, with the words República de Bolivia prominently displayed.

In her book Red Pedagogy, Quechua scholar Sandy Grande preludes the chapter “Better Red than Dead” with an ode to her grandmother: how the memory, soul and ancient culture of her ancestors are “lovingly but relentlessly, embodied within her.” I sat with this concept of the body as a source of embodied knowledge during an exercise where we had to identify the five locations along the vocal tract where Aymara consonants are produced. You could describe it as a coordinated dance with one’s lips, palate, pharynx and diaphragm to create sound-waves. They are the guttural sounds I’ve heard from various adults in my life growing up during times of festivities, convenings, and high emotions. Despite the kind encouragement of the Yatichiri, a wave of visceral emotions came over me as I was prompting my body to locate those sounds, yet failing over and over again. I am relieved I can take a step back in our virtual classroom space, cry, and put myself together before it’s my turn again. As frustrated as I was, I was also enveloped by the thought that a language I was now learning was criminalized and marginalized at various iterations of history, shaping the relationships that my parents, grandparents and now I had with this language.

What does it mean to affirm Indigenous identity on WhatsApp? The Indigenous experience is one that cannot be generalized due to the varying colonial processes, geographical factors, and characteristics of said communities. This variance also translates to social media use. WhatsApp, a leading mobile messaging platform, is used by nearly two billion people worldwide in 112 countries including in Latin America. This popularity has extended to immigrant, diasporic and refugee communities who disseminate media, news, thoughts, and feelings with relatives back home as well as where they now call home. A report from Nielsen shows that US Latinx populations between the ages of 18-34 are more than twice as likely to use WhatsApp than the general population. In New York City, delivery app workers relied on WhatsApp to organize, mobilize and connect with one another to demand better working conditions. In the WhatsApp chats, workers shared which restaurants would let them use bathrooms, which parks were safe and open to the public, and reported rumored or confirmed bike robberies, which in one instance led them to collectively retrieve a stolen bike. In New York City, most delivery app workers are Indigenous peoples from Central America such as the K'iche or of other Maya communities. Pascua Yaqui scholar Maria Duarte’s concept of Indigenous Cyber-relationality asks Indigenous/Native peoples to reflect on who they are as a people and to delineate greater goals of decolonization, which means “reducing the authority of settler oppression in their everyday lives.'' While self-determination is a core element of social media use of Indigenous communities, this value of self-determination does not only exist in overt activist campaigns but also in the quotidian ways that Indigenous peoples connect with each other online and indigenize social networking sites. I consider my WhatsApp Aymara study group as an opportunity to navigate beyond the spatial and temporal boundaries imposed by the colonial mindset. It is a space to not only represent myself, but also to build networks of relationality with other Aymara descendants North and South. This year marks the 32nd anniversary of the First Continental Gathering of Indigenous Peoples which took place in Quito, Ecuador in 1990. This event marked the first time Indigenous peoples from Abya Yala (the condor) and Turtle Island (the eagle of the north) gathered independently to reject the quincentennial anniversary of the colonial invasion of the continent and collectively ratify a political project of self-determination for the true liberation of Indigenous peoples. The act of coming together is a micro but powerful step forward in liberation. Like the K'iche delivery app workers, Indigenous peoples have long reappropriated technologies to come together and resist. Whether it be the Zapitistas who used the Internet to build trans-national solidarity in the early 90s, or projects like CyberPowWow, or the Facebook group Social Distance PowWow, these spaces maintain Indigenous presence and convening despite wherever one may be.

Artificial intelligence and the capitalist infrastructure behind tech now largely influence how we experience daily life. Power and technology colliding is nothing new. The architecture of what largely constitutes our internet today in the US was built by the US military during the Cold War era. Similarly, the federal US government has continued its tradition of leveraging control of natural resources, by auctioning and licensing of spectrum to large communication corporations over Native territories. Spectrum is essential to wireless Internet service and thus has been a point of resistance by Native activists to have more sovereignty over their own Internet infrastructures on their lands. I soon learned why our Yatichiri used WhatsApp for our first class sessions, as Zoom required higher megabits per second, which meant purchasing more expensive data packages, or as Bolivians call it, megas. When we eventually moved to Zoom, certain times of day were not possible to hold class due to Bolivia’s weak broadband infrastructure that would inevitably cause our Yatichiri’s screen to freeze. As opposed to the world’s wealthier countries, only about half of Bolivians have internet access with even greater disparity between Bolivians living in the country’s main urban areas and those in rural parts of the country. WhatsApp, owned by tech conglomerate Meta, has filled this gap in many parts of the world akin to a public utility. This dependence on apps like Messenger and WhatsApp for the communication and commerce of daily life was revealed after high profile outages of Meta’s products.

XMPP, the technology used to exchange WhatsApp messages, is an open communication protocol. Favored by activists and hackers due to its decentralized and extensible protocols, it was originally created with open use in mind yet valuing privacy and illegibility. I, however, was oblivious to this, which is not a coincidence but rather a long-standing tradition of algorithmic opacity that the tech industry encourages. I realize that even in tech, protocols are not simply a set a guidelines but have the capability to ensure that people and their environments can thrive and be safe.

So how do Indigenous peoples exist in virtual spaces? Indigenous technologists have long contended with these questions. The Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Working Group and the Global Indigenous Data Alliance indicate that tech creators should account for the following central tenets: power differentials, historical contexts and supporting Indigenous self-determination when developing technologies used by Indigenous peoples. In a talk last year, Jason Edward Lewis, a digital media theorist and software designer, offered a hopeful take on the place of AI for the future. Indigenous epistemologies, guided by specific territories, genealogies, and protocols, “provided a unique opportunity to better accommodate kinship networks beyond humankind respectfully and reciprocally.”

Learning Aymara on WhatsApp produced a third space through digitally-afforded rituals and gestures. This was meaningful because Aymara, like other Indigenous languages, represents knowledge that is simultaneously relational and territorial, similarly to a guide. Nearly three years later, that decision, through embodied memory, has renewed a commitment to continue to develop and articulate kinship networks found within my ancestral lands of Qullasuyu. Our Aymara study group renewed these commitments by regularly revisiting this knowledge and engaging with one another.

It is a gateway that provides connection despite the distance, despite loss of time, despite the obscurity. A gateway seemingly powered by a server and the exchange of data, but in reality powered by one another.

Jichuruxa, kullakita @Yvette Ramirez nayampi parlapxawa...

Today kullakita Yvette and I will talk 🤗🦜 (catch up, visitar virtualmente)

—

*For those interested in virtual Aymara classes, contact Eber Miranda at: rodolfomiranda244@gmail.com

Yvette Ramírez is a researcher & archivist based in Detroit, MI, by way of Queens, NY. Her research is inspired by the complexities of memory and information transmission within Andean and other diasporic Latinx communities of Indigenous descent.

Currently, she is working towards her PhD at the School of Information at The University of Michigan where she also holds an MSI in Digital Curation and Archives. Yvette is a also a co-founding member of the collective Archivistas en Espanglish; you can follow her work at @yvettegramirez on Instagram or Twitter.