On Epidemics and Quarantines: Lessons from Latinx History

History shows that epidemics and quarantine expose the near invisible labor that makes reproduction and survival possible in transnationally connected communities.

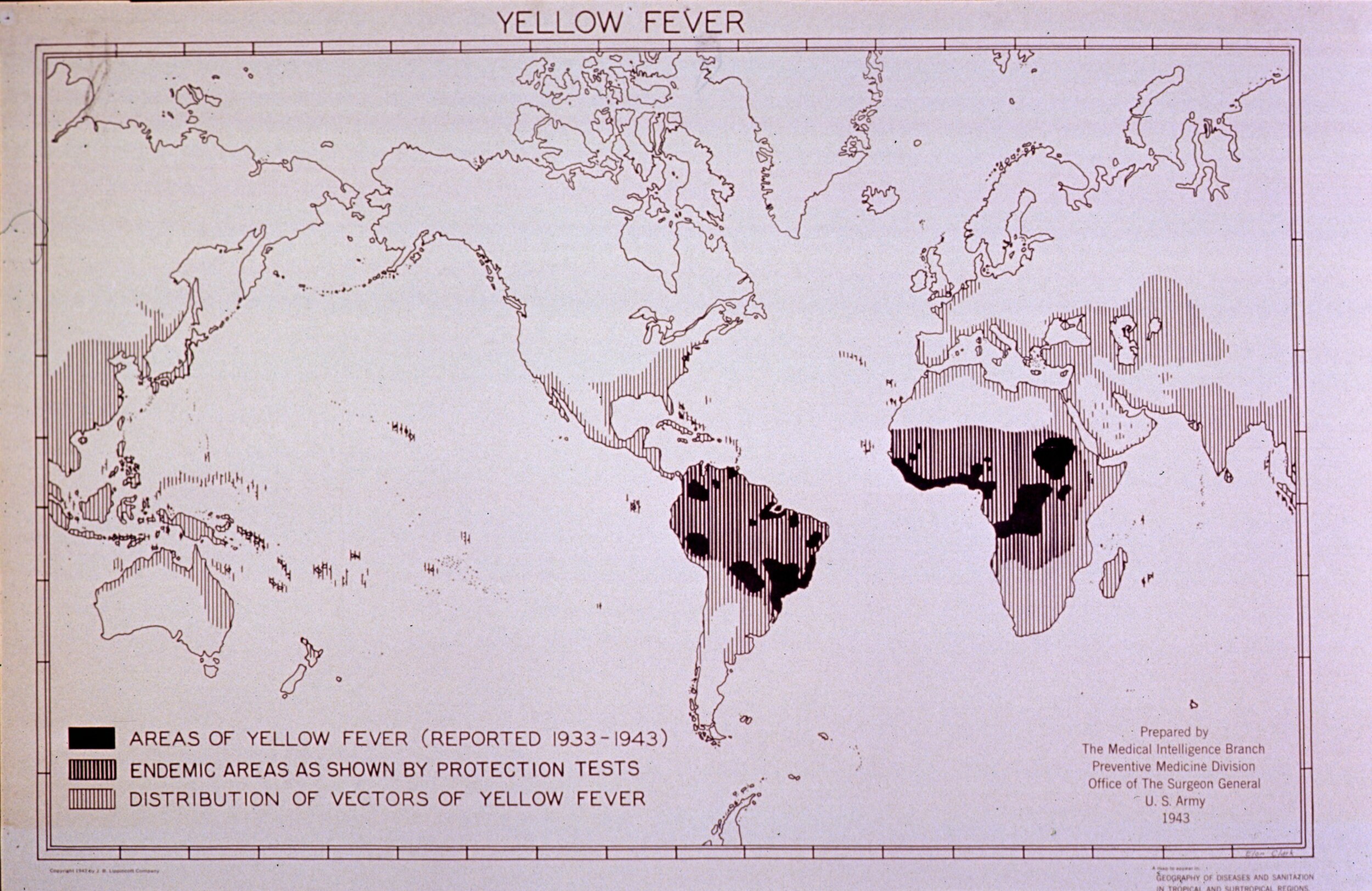

Let us begin a consideration of quarantine with the last yellow fever epidemic in Texas.

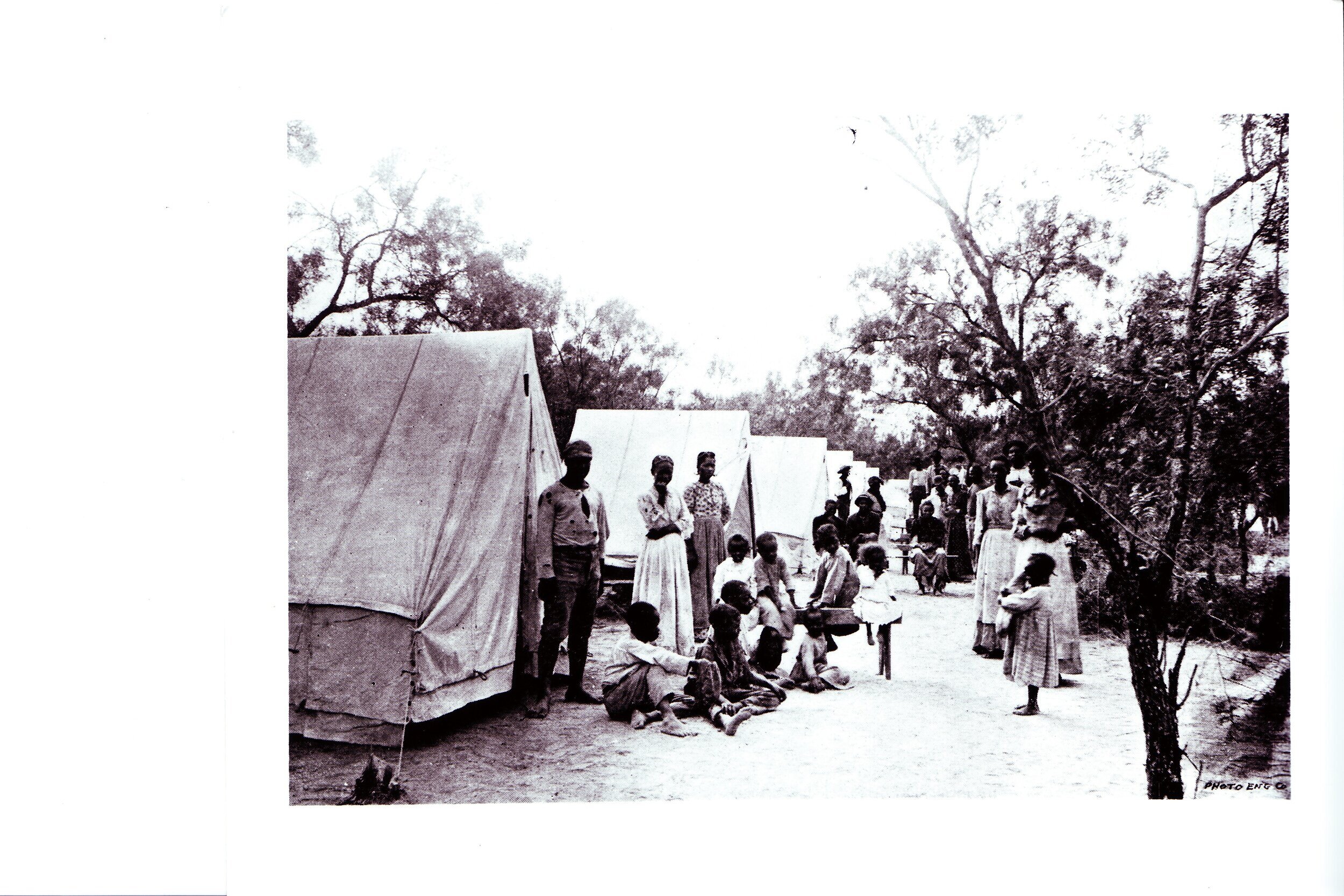

In August 1903, the federal government applied a full quarantine on Laredo due to reports of yellow fever cases in Laredo and Monterrey. No entry, besides emergency personnel such as U.S. Marine Hospital Service [USMHS] Officers, elected officials, and soldiers in the 10th cavalry. The US Marine Hospital Service left the rest of the town to fend off the threat of yellow fever and military quarantine. Fifty seven domestic workers—quarantined and trapped in Laredo during a yellow fever epidemic—wrote and translated a petition challenging the way privilege got re-worked in this epidemic and quarantine:

“We, the undersigned, being mostly widows with families to support with our own hands, would represent that on account of the pest which has most unfortunately attacked our city, most of the well-to-do families that have given us employment in doing their washing, ironing, sewing and etc., have left the city; that since then we have been unable to find any work and we have been thrown suddenly wholly on our own feeble resources, with large families to support and no means of doing so. Hence we humbly petition the Honorable Mayor and the Board of Aldermen either aid us in obtaining work or to furnish us means with which to support ourselves and our families while this epidemic lasts.”¹

In Laredo, the well-to-do, unlike most of the United States, were constituted by wealthy Mexican landowners, business owners, and Anglo or creole migrants who married into this not quite American wealth. These women argued that their intimate and public labor kept appearances and businesses going before and after these epidemic crises.² Moreover, their presence in the city retook the mantle of political authority abandoned by the local political elite who fled Laredo to become ‘yellow fever refugees’ in San Antonio and central Texas. These women and their working-class Mexican neighbors stepped into the political vacuum created by the epidemic and forced federal authorities to concede resources, political power, and household claims to people Cuban-born USMHS surgeon Gustavo Guiteras called “almost entirely of the lower class, ignorant and superstitious.”³ Nevertheless, these women demanded their due and the quarantine cleared the way for this gesture.

Yellow fever, like COVID19, created deep anxieties. It caused extensive internal bleeding, required hospitalization or extensive palliative care, and had close to a 1% mortality rate. Demanding reciprocity and resources from the powers that be in the midst of a frightening epidemic shows us that life must be enabled to continue, even under quarantine.

Their gesture, asserting working-class power in the midst of a state of emergency, goes against a commonly shared understanding of quarantine: public health officials declare and people follow. Latinx scholars and Latinx communities subject to U.S. policies and practices have asked people to take a closer look at life under quarantine, to consider who bears the impact of these states of emergency and who reaps the benefits of controlling movement across spaces defined as suspect and requiring constant surveillance and policing.

Ongoing reports regarding COVID19 have razed the assumption that somehow we are better equipped to deal with communicable diseases than people were in the past. Given that scholars are now using the 1918 avian flu pandemic to gauge the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions like social isolation, mitigation, patient segregation and quarantine, we should also start investigating whether quarantine against communicable diseases has placed an uneven burden on Latinx communities and communities of color across the United States. Given the possibility and reality of quarantine, it is also important to understand how different communities dealt with the reality of epidemics and quarantine in their lives in the United States. The contention here is that many Latinx communities have been consistently subject to quarantine like situations, their movement limited and policed.

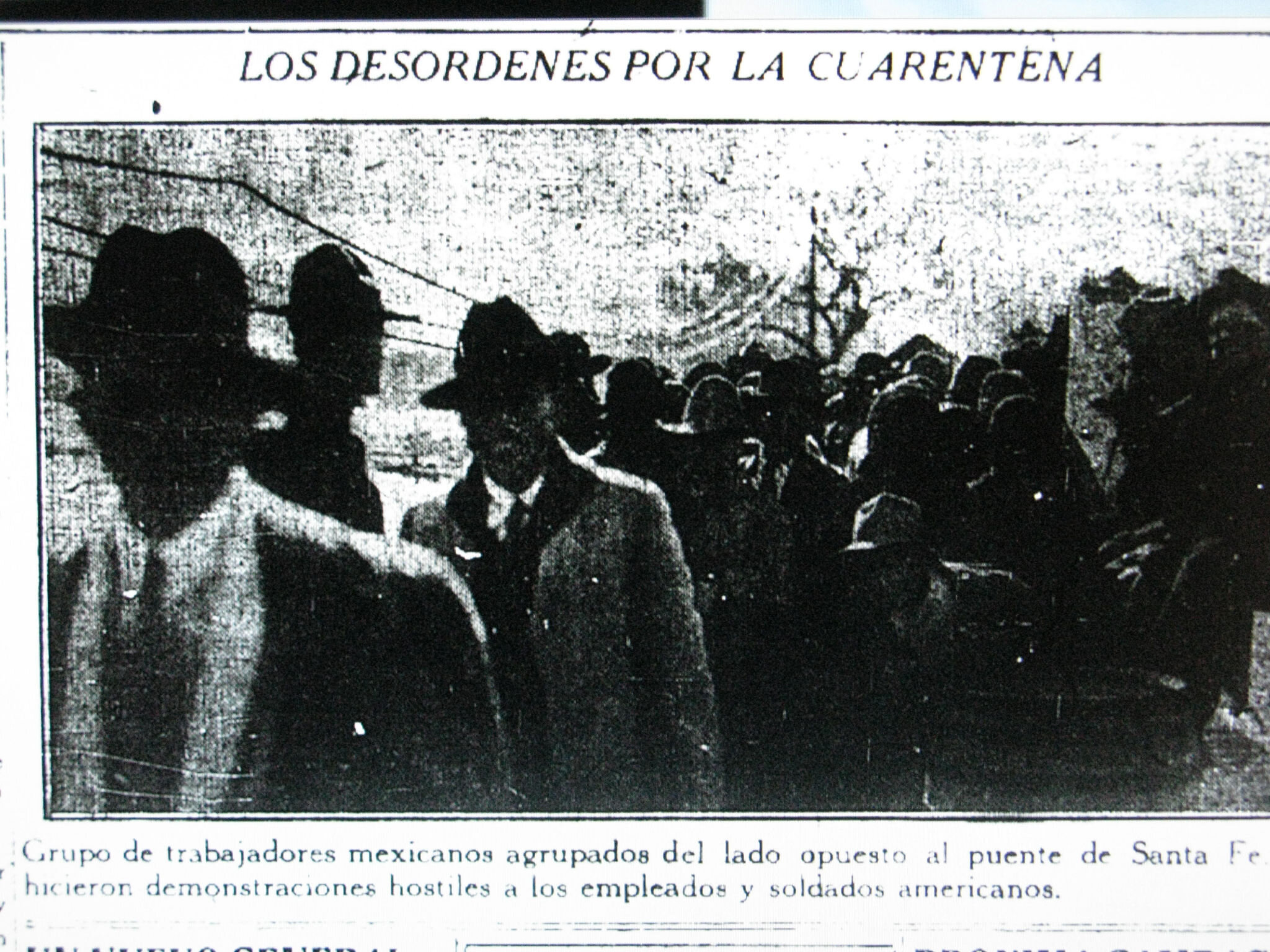

My first book, Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas-Mexico Border, 1848-1942, explored how interconnected Mexican, Black and Anglo communities negotiated sixty years of a nearly unbroken series of federal quarantines and emergency measures. Women, in particular, demanded a fuller accounting of their sanitary and intimate labor, from the demands that the US Marine Hospital Service deliver food and treatment to people in Brownsville caught in the “Texas-Mexican Fever” quarantine of 1882 to Carmelita Torres and her fellow commuters physically challenging the ethics of forcing cleansing baths on people who cleaned clothes and houses in 1917 El Paso. Though the typhus quarantine ended with WWII, airline passengers leaving Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia and Central America have vivid memories of being sprayed with DDT upon landing in the United States. This, of course, pales in comparison with the ritual DDT cleansing Braceros—from Mexico, Puerto Rico and Jamaica—faced during inspection and crossing into the United States. Quarantine shaped Latinx communities border crossing experiences in the United States.

Quarantines did not merely affect people crossing into the United States. The rhetoric of quarantine also shaped the ability of people to benefit from public policies. Inspectors for the Home Owner Loan Company drew redline maps of the United States combined the appearance and possibility of disease with ethnically mixed nature of Latina/o neighborhoods like the South Bronx, South El Paso, East LA, and West Side San Antonio to quarantine their residents from receiving the benefits and guarantees the federal government provided other renters and homeowners.⁴ The act of deeming certain areas medically suspect shaped the life chances of those neighborhoods. Quarantines, modified as they have been to permit workers and goods to come to the United States, have been an ongoing gatekeeping device shaping Latinx belonging in the United States.

The other issue Latinx scholars have raised about quarantine is the geopolitics of it all. Mariola Espinosa has traced a longstanding desire by U.S. officials, medical authorities and media pundits to take control over Cuba to prevent the appearance of yellow fever in ports opening out to the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico.⁵ Part of the justification and desire for U.S. control over Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and even ports like Veracruz, Buenaventura and Barranquilla lay in a U.S. anxiety that their authorities were not doing enough to protect U.S. lives and commerce, that with U.S. control, “[they] cannot then indulge [their] peculiar ideas of epidemics without involving some of the rest of us.”⁶ This anxiety regarding control over contagion shaped Latinx autonomy in the United States. Natalie Lira, Nicole Novak, Alexandra Minna Stern and Miroslava Chavez Garcia demonstrated how anxieties about disability led to the sterilization of California youth housed in state youth asylums.⁷ In How Race is Made, Natalia Molina has documented how, beginning in the 1920s, city and state authorities in California used syphilis and TB diagnoses to justify the expulsion and deportation of Mexicans of all nationalities to Mexico.⁸ Much of the fear across different communities is that this state of emergency will give companies and unelected authorities (organizations analogues to Laredo’s well-to-do) the justification to implement policies that would not pass regular political debate or muster.⁹ The recent push across Puerto Rico and its diaspora to make officials accountable for the ways they treat Puerto Rican lives as disposable is a reiteration of politics against a state of emergency.¹⁰ These movements are part of the many battles that grassroots communities have waged to transform political authorities during the states of emergency that, far too often, shape Latinx lives and communities across the United States empire. We should heed the demands laid by 57 women under quarantine in Laredo in 1903, and provide the time, food, rent and health care necessary to keep people alive and in a working democracy.

Born in Queens, John Mckiernan-Gonzalez grew up in Colombia, Mexico, and the U.S. South and brings a migrant eye and experience to his projects in public history, medical history, and Latino studies. He is the Director of the Center for the Study of the Southwest, the Jerome and Catherine Supple Professor of Southwestern Studies, and an Associate Professor of History at Texas State University. He worked in HIV before beginning his graduate training at the University of Michigan. His first book, Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas-Mexico Border, 1848-1942 (Duke, 2012), treats the multi-ethnic making of a U.S. medical border in the Mexico-Texas borderlands. He co-edited the volume, Precarious Prescriptions: Contested Histories of Race and Health in North America (University of Minnesota, 2013) which examines the contradictions and complexities tying medical history and communities of color together. His broad takes on Latina/os in U.S. medical history can be found in American Latinos in the Making of the United States and in Keywords in Latina/o Studies (NYU, 2017). His next project, Working Conditions: Medical Authority and Latino Civil Rights tracks the changing place of medicine in Latina/o/x struggles for equality.

List of References

James Saunders (Justo) Penn, “Asking for help. A petition to the City Council from Fifty Seven Women,” Laredo Daily Times, October 19, 1903, 3.

Leonor Villegas Magnon, La Rebelde (Houston: Arte Publico Press, 2004).

Guiteras, “Report on the Epidemic of Yellow Fever of 1903,” 304.

Full quote for South El Paso: “D3: This large area is the concentration of Mexican peons which constitute the largest class of Mexican laborers. All of the shacks therein are very poor and there is positively no demand of any kind for property in this section. This area, as well as all other Mexican sections, is avoided by mortgage lenders.” “El Paso, TX,” Mapping Inequality: Redlining in America, American panorama.

Mariola Espinosa, Epidemic Invasions: Yellow Fever and the Limits of Cuban Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

John Hunter Pope, “The Condition of the Mexican Population of Western Texas in Its Relation to Public Health,” in Public Health Papers and Reports, vol. 6, ed. American Public Health Association (Boston: Franklin Press, Rand and Avery, 1881), 162.

Novak, N. L., Lira, N., O’Connor, K. E., Harlow, S. D., Kardia, S. L. R., & Minna Stern, A. (2018). Disproportionate sterilization of Latinos under California’s eugenic sterilization program, 1920-1945. American journal of public health, 108(5), 611-613. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304369. Miroslava Chavez Garcia, States of Delinquency: Race and Science in the Making of California’s Juvenile Justice System (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

Natalia Molina, How Race is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

Naomi Klein, Shock Doctrine: the Rise of Disaster Capitalism (NY: Metropolitan Books, 2010).

Yarimar Bonilla, Aftershocks of Disaster: Puerto Rico Before and After the Storm (NY: Haymarket Books, 2019). See also #puertoricosyllabus and #rickyrenuncia.