A Balm for Raceless Latinx Reading Injuries

As The New York Times and The New Yorker release their “best books of 2024 (so far)” lists, it occurred to me that 2024 has been an incredible year for reading the work of Latina writers across multiple genres. Seeing ourselves reflected in U.S. English literature is especially joyous given how infrequently the publishing world accords space to Latina authors. Yet it is, of course, impossible for any single author to represent the full complexity of all our Latina identities. For instance, while Xochitl Gonzalez’s Anita de Monte Laughs Last was a much-anticipated Reese Witherspoon Book Club and Book of the Month book release in 2024, not all Latinas could relate to the novel’s account of a working-class, first-generation Puerto Rican student’s experience at Brown University.

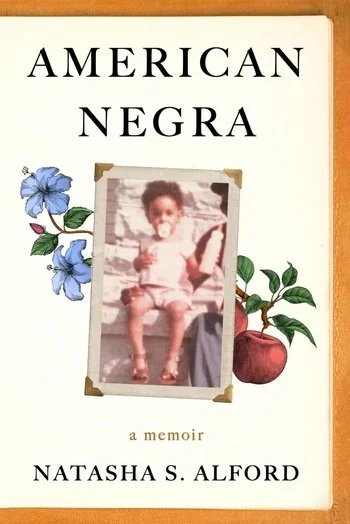

Certainly, the specificity of a novel’s details is what enriches a narrative, but it can also exclude universal identification even for Latinas hungry to see their lives reflected in print. Yet, what does it mean when a reader who is a working-class Puerto Rican first-generation student at Brown University not only does not recognize herself in Gonzalez’s Anita de Monte Laughs Last, but experiences the book as a form of alienation and melancholy? After reading Natasha S. Alford’s 2024 book American Negra: A Memoir, I realized the source of the cognitive dissonance with Gonzalez’s novel and so much of Latinx literature—the characterization of Latina ethnicity as raceless.

The irony is that Latina authors often receive praise for illuminating the racial experiences of Latinas in the United States. Overlooked in that celebration is the complication that living in a Latina body is not a raceless experience nor a singular racial experience. Racialized as White, Black, Asian, Indigenous, and mixtures thereof, these categorizations matter to how one experiences Latinidad.

One scene from Gonzalez’s book illustrates this tension. As protagonist Raquel attempts to adapt to student life at Brown University, a predominantly White Ivy League institution, she runs afoul of a group of mean girls who bully her and demand that she verbally agree to their view of her as an undeserving affirmative action admission.

Despite the fact that Rachel is clearly a street-smart, independent firebrand, she cowers before the mean girls who verbally abuse her, leaving her seemingly defenseless. In other words, she folded like a person completely surprised by the racial attack and without the skill set for fighting back. This reveals how even a “raceless” Latina has racialized expectations—that is the expectation that others treat them as a non-racialized White person. An Afro-Latina would not feel shock because she would never presume that people view her as raceless. Being an unambiguously Black Afro-Latina means knowing that your Blackness is always visible.

“Alford’s clarity about the relevance of Blackness to Latinx identity serves as a balm for feeling invisible to raceless Latina authors.”

It is for that reason that American Negra is particularly meaningful. Alford’s clarity about the relevance of Blackness to Latinx identity serves as a balm for feeling invisible to raceless Latina authors. Like the fictional Raquel in Anita de Monte Laughs Last, Alford attended Harvard, an institution similar to Brown. And like the fictional Raquel, Alford’s education was a possibility because of the scholarships she earned. Yet, as a first-year student in 2004, Alford is acutely aware of the color lines in Latinx college life, even six years after the fictional Raquel entered her own Ivy League college in 1998.

As Alford observes in her book:

“Walking into [Latinx] meetings with fewer Black people reminded me of the otherness I felt as a child in all-Latino circles with Mami, where I was the darkest and couldn’t participate in conversation.”

Moreover, Alford eloquently describes how fellow Latinas can truly love us while not comprehending what Blackness means to Afro-Latinas. In a passage about her own mother, Alford notes:

Mami could not entirely help me interrogate my morena status, in society, my negritude, as she did not fully understand her own. She hadn’t learned much about slavery in Puerto Rico or the Black Puerto Rican leaders, like Marcos Xiorro, who had revolted and fought for freedom on the island.

In her memoir, Alford reflects on her origins as a child born to a Puerto Rican mother and African-American father, raised in the racial isolation of Syracuse, New York. The book traces her journey from Syracuse to Harvard and then finally to her career as

an award-winning journalist for both TheGrio and CNN. But unlike so many other coming-of-age chronicles about racial identity, Alford helps the reader understand that racial identity is not a singular story existing in a vacuum divorced from social context and collective histories. Alford is racially literate and a writer adept at bringing in insights from race scholars in a clear and accessible manner. The result is a book with an engaging life story that also enriches our understanding of how systemic racism influences racial identity.

“Alford helps the reader understand that racial identity is not a singular story existing in a vacuum divorced from social context and collective histories.”

Putting American Negra into conversation with the body of raceless Latinx literature is a public service. This is because the book not only educates, it also serves as a salve for the reading injuries of colorblind Latinidad—for instance, deracinated depictions of Lukumí (an African-based religion) that pervade Anita de Monte Laughs Last and other Latinx books. American Negra is on my “best of 2024 (so far” list, and I recommend you consider it for your own.

Tanya Katerí Hernández is the Archibald R. Murray Professor of Law at Fordham University School of Law, where she serves as an Associate Director of its Center on Race, Law and Justice. She received her A.B. from Brown University, and her J.D. from Yale Law School. Professor Hernández is an internationally recognized comparative race law expert and Fulbright Scholar. Her most recent book from Beacon Press is Racial Innocence: Unmasking Latino Anti-Black Bias and The Struggle for Equality, and its Spanish Translation edition, Inocencia Racial: Desenmascarando la antinegritud de los latinos y la lucha por la igualdad.