Estrangement, Restlessness, and Rupture: Pablo Delano and the Rethinking of Puerto Rico

“Yo sabré siempre quererte, como llorar tus pesares…”

–Lola Rodríguez de Tió, A Puerto Rico, 1893¹

The Museum of the Old Colony: An Art Installation by Pablo Delano was hosted by the Duke Hall Gallery of Fine Art at James Madison University from February 1 to March 26, 2022.² Curated by art historian Laura Katzman, this conceptual exhibition addresses how the U.S. “territory” of Puerto Rico—a Caribbean archipelago—has been represented in 20th-century archival photographs, media images, tourist objects, historical artifacts, and films. It has recently been memorialized in a new eponymous book—the first to extensively document and interpret Delano’s open-ended, multimedia installation. Five insightful and well-researched essays by Katzman, Laura Roulet, Amanda Guzmán, César Salgado, and Beth Hinderliter, a foreword by Marianne Ramírez Aponte, and a 3-D visualization by Ángel Garcia, Jr. offer illuminating aesthetic, historical, anthropological, and political perspectives from which to view The Museum of the Old Colony and to grasp its many implications.³ This impressive publication has inspired me, a writer on Caribbean literature and culture, to meditate even more deeply on Delano’s performative project—itself a meditation on museums and archives—which intellectually and emotionally drew me into its compelling universe from the moment I entered the exhibition space.

Delano, a visual artist and photographer born in San Juan and based in Hartford, Connecticut, simultaneously reconstructs and challenges the imperialist vision of Puerto Rico after the Spanish-Cuban-American War of 1898—occasionally including other islands such as Cuba, Hawai’i, and the Philippines. The Museum of the Old Colony evokes André Malraux’s concept of a “museum without walls,” which emphasizes the value of photography in broadening the scope of art collections (and by extension its power to perpetuate myths and stereotypes). Relatedly, the artist subversively plays with the representation of the “other,” as created by Western anthropological and ethnographic institutions whose displays have rationalized the “right” of imperial powers to subjugate peoples they have conquered and attempted to control. Yet The Museum of the Old Colony is nomadic in nature, characterized by itinerant movement and flexibility, changing shape and thus accruing new meanings as it adapts to each new space that hosts it.⁴ (Ironically, while this fictive museum critiques museums, it also belongs to one; an earlier version of the installation is part of the permanent collection of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico.)

As the most extensive iteration of The Museum of the Old Colony to date, the Duke Gallery venue gave expansive breadth to Delano’s satirical mimicking of the role of collector. His selective appropriation and repurposing of “found objects,” purchased memorabilia, and historical photographs tells a cultural story about his native country through the critical gaze of an insider. For the artist, the chronology of Puerto Rico is not marked by historical milestones, but rather by the evolution of a manufactured commodity fraught with associations of the colonizer and the colonized: the Old Colony soft drink, whose name Delano uses to title his installation in a Proustian moment of confession. With wry humor, we learn that the artist himself drank this sweet yet unhealthy beverage as a child growing up on the island.

Everything in this installation is multilayered, each tableau containing a cacophony of voices. In one of the stations, “At the Crossroads,” chaos arises, as a Buddha doll, an American B-52 toy airplane, a jar of Vicks VapoRub ointment, and several elements of Afro-Cuban religion—Santería necklaces and The Infant of Prague—refer to a mixed and transcultural reality where foreign, imported, or outsider influences mingle with native traditions, all recontextualized in a space marked by the heterogeneity that nurtures Puerto Rican identity.⁵ This ensemble is animated by an echo chamber where all voices resonate, in a clear effort to appeal to a collective yearning around the national trauma of a never-reached independence. An exploration of mourning is a recurring leitmotif—a critical evocation of loss and striving that can be traced across Puerto Rico’s history in the twentieth century. This journey becomes an antidote to the erasure of countless narratives torn between resistance and assimilation.

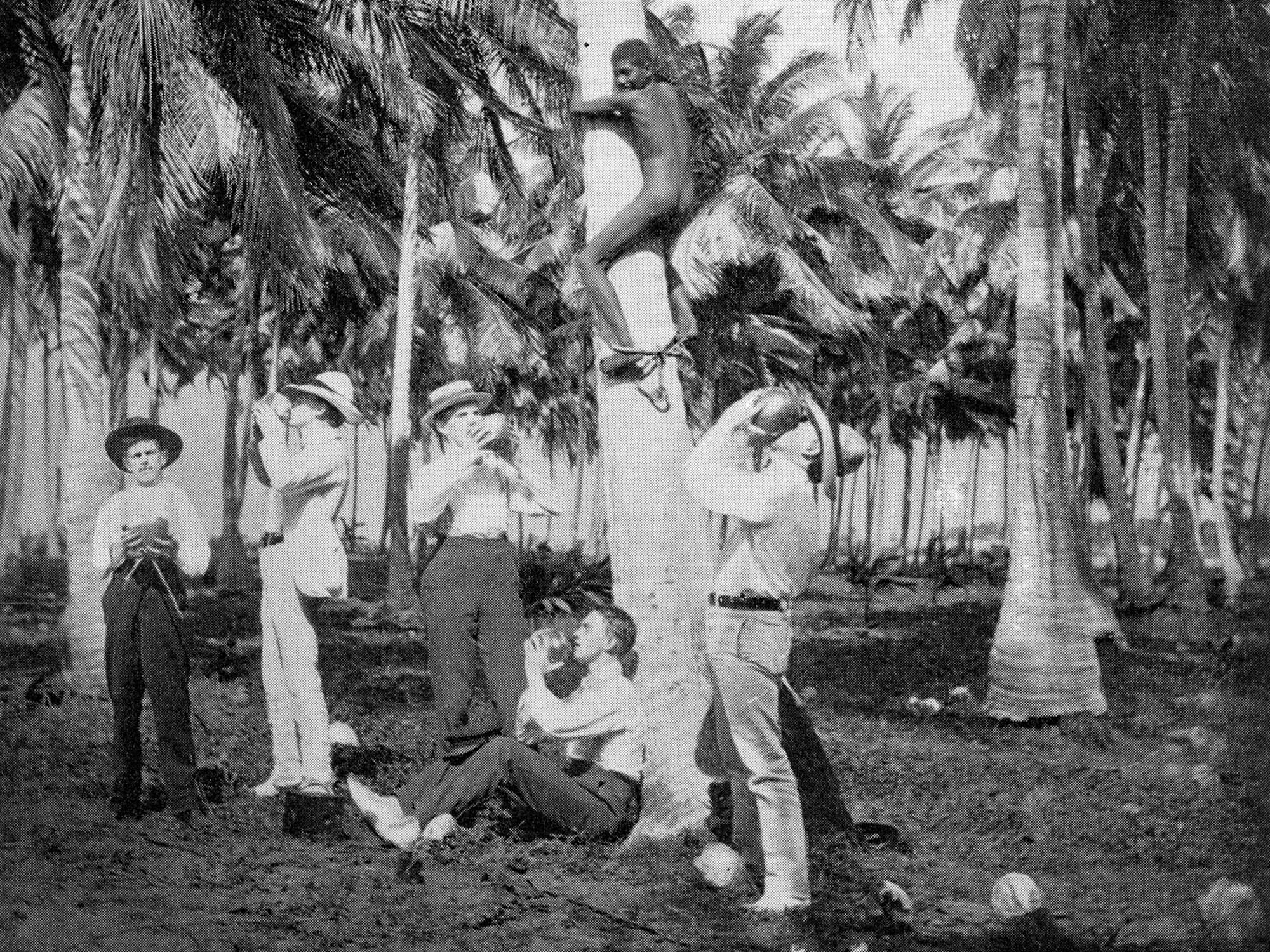

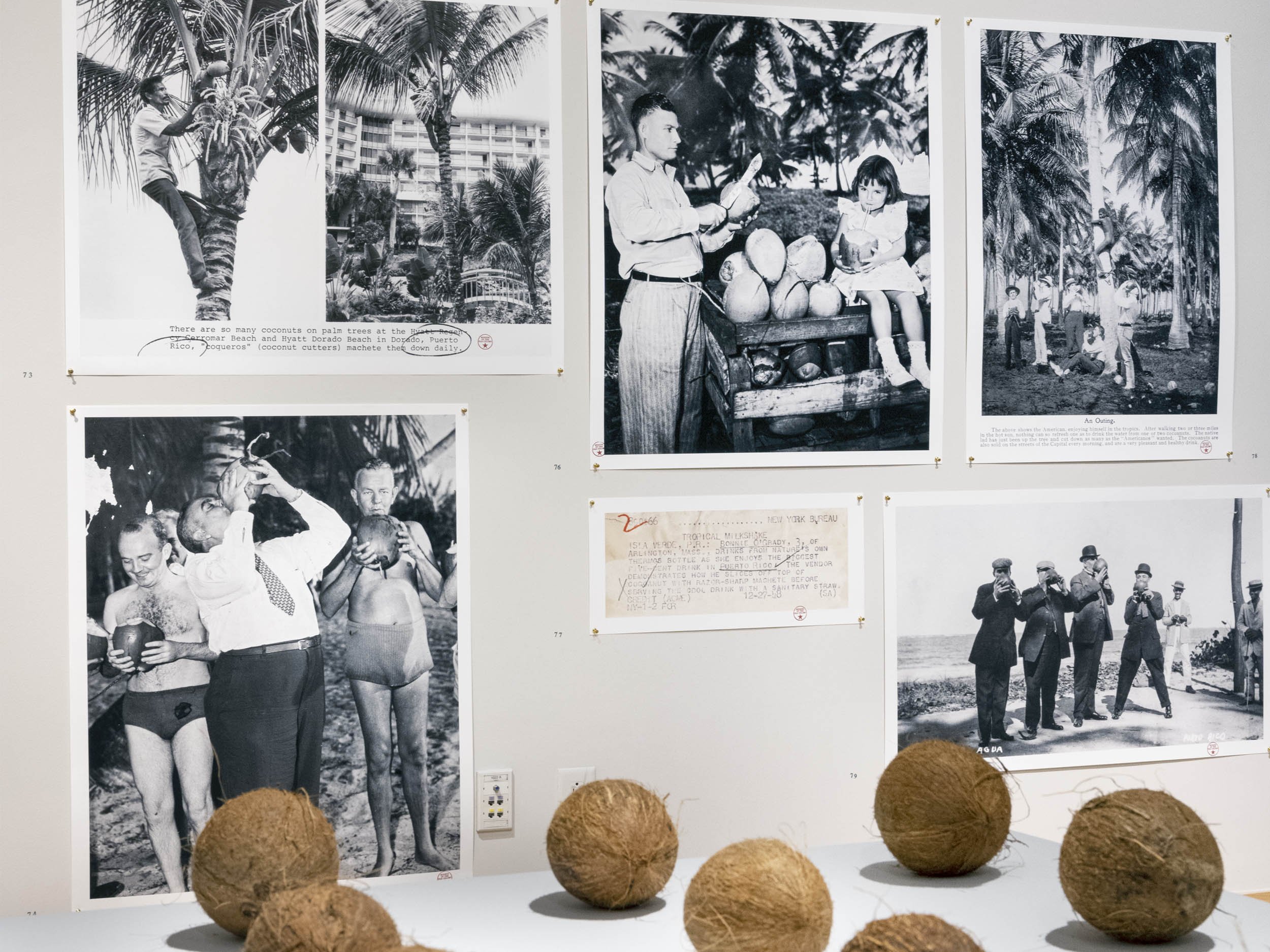

Throughout the exhibition, Delano enlarges his photographs (or scans) of the original photographs and captions he appropriates, reproducing fragments of iconographies and discourses recovered from books, newspapers, magazines, press releases, albums, and catalogues, among other sources he acquires. This compels viewers to confront a reality of domination that exudes psychic and symbolic violence. From these visual and textual excerpts of a controversial colonial corpus, Delano makes it impossible for spectators to look away from images of the 1898 era, such as “An Outing”—one of the saddest and most enraging photographs in the entire ensemble—in which a naked Puerto Rican boy climbs a palm tree, while North American tourists in the shade drink the refreshing water from the cocos he has retrieved for them. Laura Katzman analyzes this image in relation to a more modern photograph using similarly demeaning tropes of a decently dressed yet barefoot coquero performing the same activity at a luxury hotel. Such “provocative juxtapositions” show how colonialism persists even as Puerto Rico has modernized and gained some political autonomy since the 1950s.⁶ As the artist stated in “The Decolonial Paintbox: Three Projects 1996-2021,” a talk he delivered at Trinity College in October 2021: “Colonialism is not just a historical concept when you live it.” This speaks not only to Delano’s empathy for what Susan Sontag has termed “the pain of others,” but also to his palpable sorrow about his own lived experience of the tragic colonial condition.

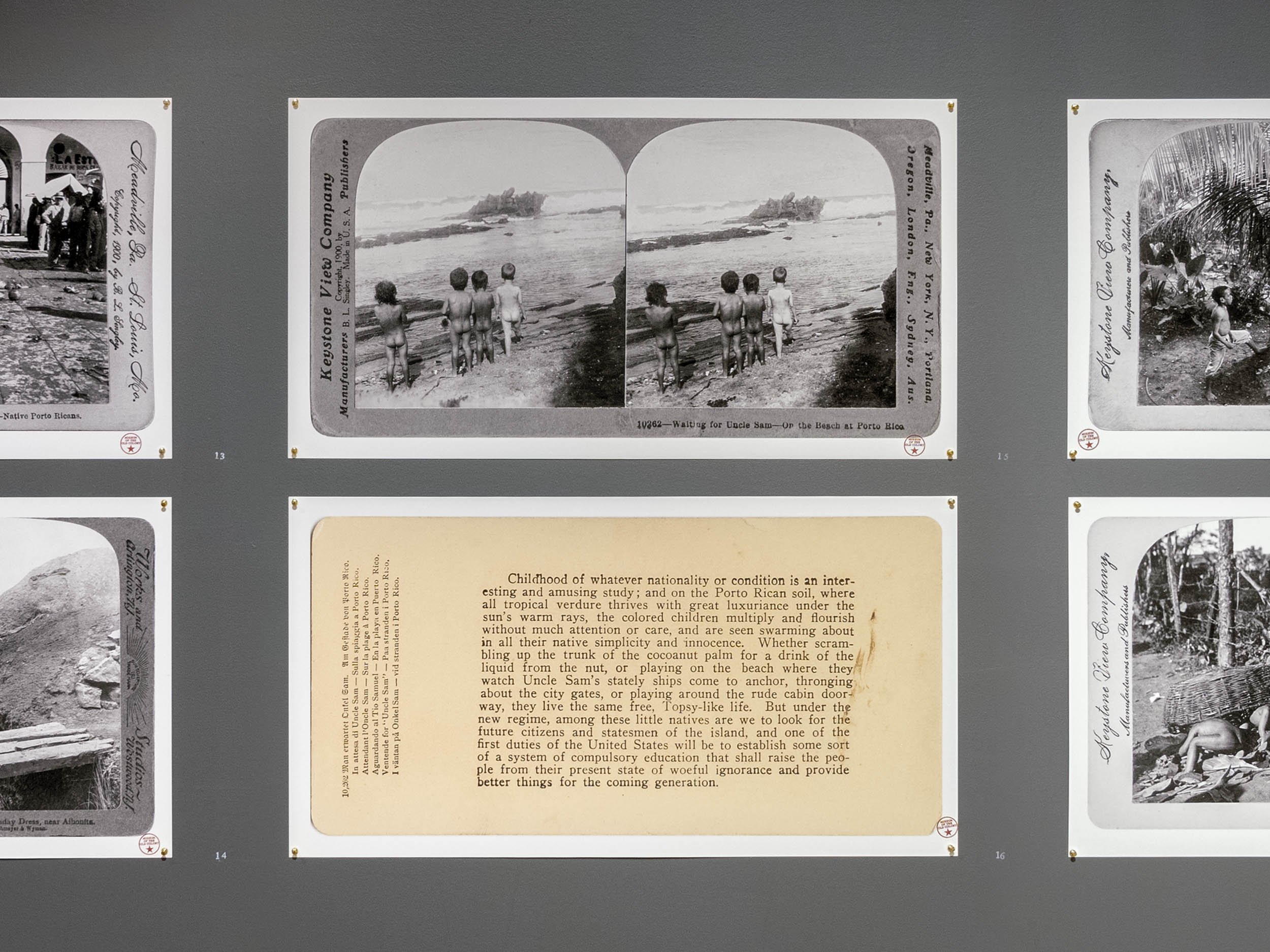

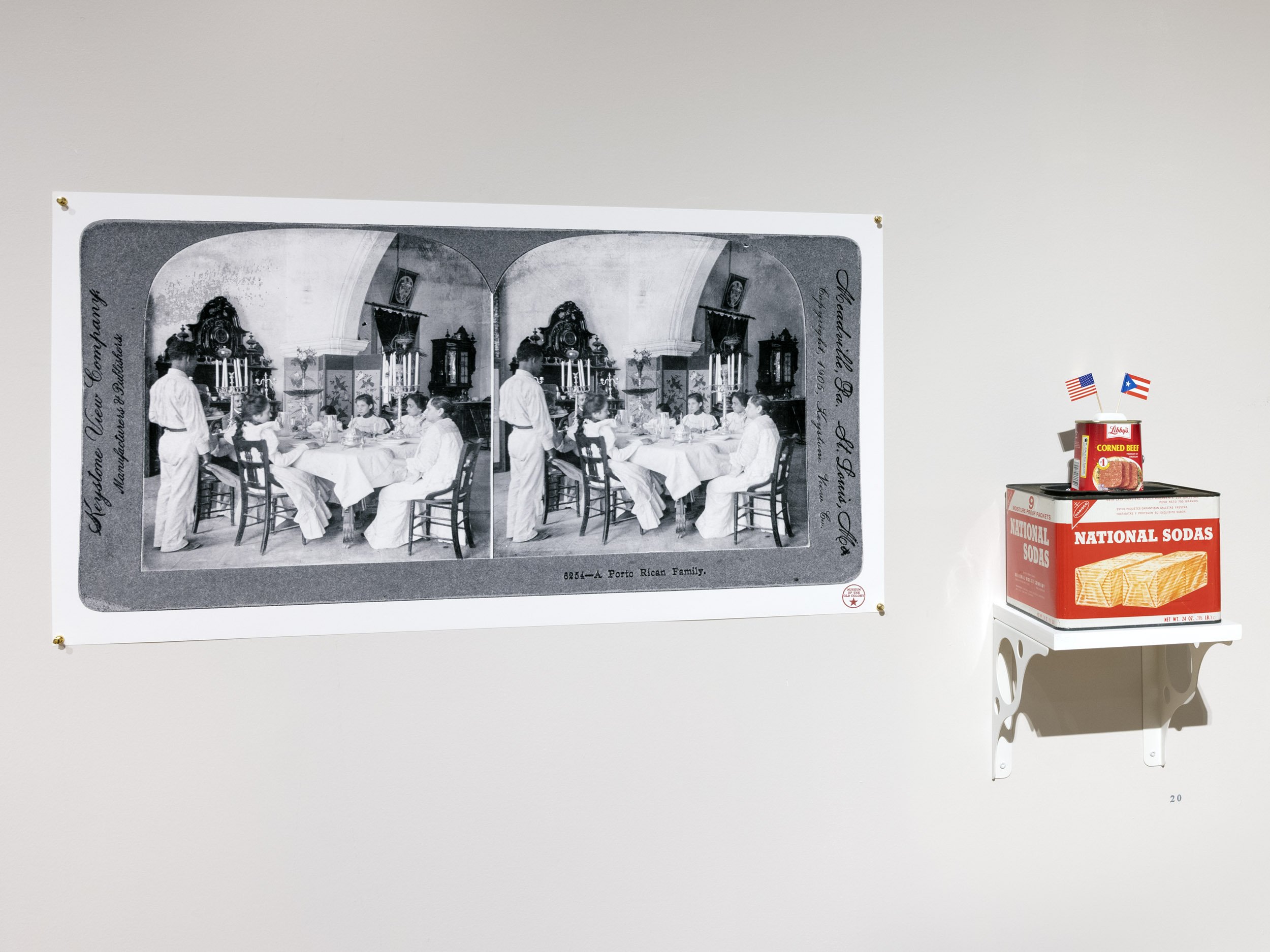

Delano is not interested in presenting a one-dimensional picture of Puerto Rico; on the contrary, the imagery and objects he employs form a kaleidoscope that encompasses Puerto Ricans of Taíno, African, and Spanish heritage. Images of dark-skinned children naked or in rags who stand at the edge of the ocean waiting to be “saved” by the invisible U.S. “savior” contrast with depictions of more privileged Puerto Ricans of White, Spanish descent in “A Porto Rican Family.” But upper-class elites do not escape the colonizer’s “othering.” The installation delineates a map in which Puerto Ricans represent figures who—even when created from stereotype and masquerade such as the legendary jíbaros—describe the myriad essences of a national character. Indeed, Delano features a diverse set of Puerto Rican figures—real and imagined—on equal terms. Nationalist revolutionary Lolita Lebrón; Yaucono coffee mascot Mamá Inés; San Juan mayor Felisa Rincón de Gautier (doña Fela); Miss Puerto Rico of 1952, Helga Monroig; and a Puerto Rican Barbie doll all coexist in his museum not to promote a hierarchy of significance but rather as true counterpoints to generate dialogue and debate.

Perhaps because many of Delano’s memories of Puerto Rico belong to his early years and adolescence, he emphasizes the presence of childhood. Boys and girls appear “used” and “reused” in colonial iconography as analogies for the “abandoned island,” in need of shelter, protection, and guidance. Images of destitute children transition to those of impoverished young women who must be “rescued” and to photographs of sexualized teenage beauty queens and women objectified in other ways. The exhibition can thus be read from the perspective of a gendered infantilization of Puerto Rico; the archipelago emerges as vulnerable not unlike small children and stereotyped women. The merging of gender and infantilization also occurs in the tableau of the male toy soldiers marching among the colonizer’s literature on Puerto Rico—reinforcing the militarization of the “territory” under U.S. rule. The recontextualization of objects associated with childhood play provokes in viewers feelings of estrangement, restlessness, and rupture, which, in turn, invite us to reflect on the macabre underside of what at first seems familiar, naïve, or innocuous.

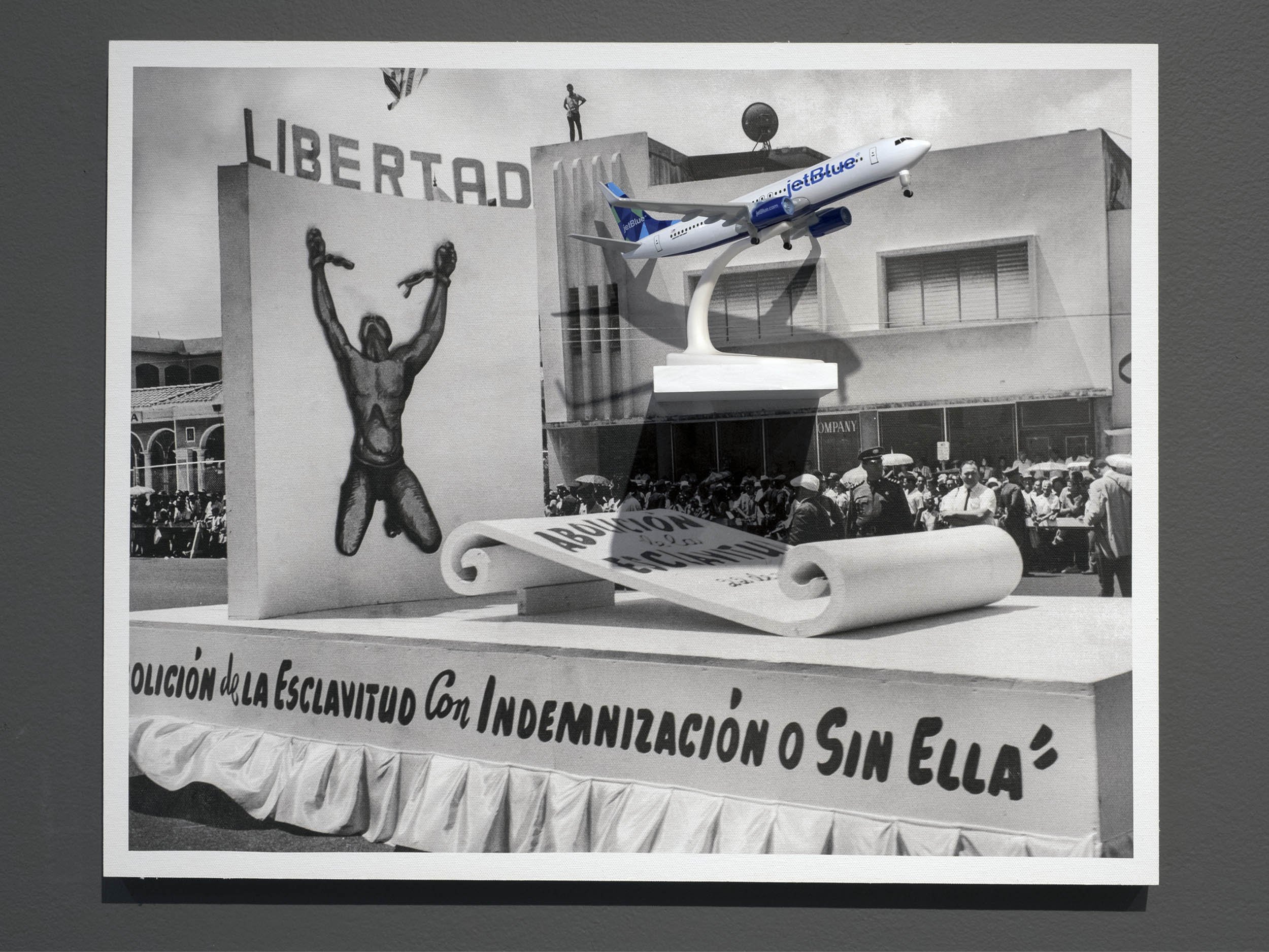

A work like “A Once Sleepy Colony” calls to mind the presumed passivity of Puerto Rico in its attempts to become independent—a theme represented by the educational toy “Soft and Safe Hispanic Family” with its “squeezable” plastic dolls. Such passivity is countered by Nationalist action, as seen in images of Puerto Rican independence fighters and the state forces that repressed their uprisings. With Delano’s recovery of these heroic stories, the artist weaves together seemingly contradictory threads of Puerto Rican history, which center around the coexistence of nationalistic feeling with the reality of massive migrations to the U. S. continent. Delano highlights historic and contemporary realities for Puerto Rico, where escalating economic crises and ever more deadly and frequent natural disasters continue to condition mass exodus. As Yomaira Vázquez-Figueroa reminds us, the year 2015 marked a historic moment in Puerto Rico’s migration history because at that time there were officially more Puerto Ricans living in the U.S. than on the island.⁷ (This was only exacerbated by Hurricane Maria in 2017.) Delano’s preoccupation with this issue is expressed more elaborately in a new work entitled “The Jet Blue Solution,” from his recent exhibition cuestiones caribeñas/caribbean matters at Trinity College’s Widener Gallery.⁸ Against a photograph of a parade float sanctioned by the government to commemorate the emancipation of enslaved Africans in Puerto Rico, Delano places a Jet Blue airline toy plane, poised for takeoff, presumably to the U.S. This suggests tensions between different kinds of “freedom” that have coexisted in the “Free Associated State” of Puerto Rico—tensions that continue to influence the destinies of Puerto Ricans on the island and in the diaspora.

The Museum of the Old Colony, however, stays mostly in Puerto Rico—with its historic plantations, beaches, and oceans, and its more urban spaces—the incipient city found in images of home interiors and neocolonial “precincts” such as banks, hotels, and militarized enclaves. “The Museum Desk” is one such enclave; it turns the viewers’ gaze on the colonizer—the imagined 1898-era military occupant of the desk, replete with his colonial books, artifacts, and instruments of measuring and photographing “our islands and their people.” Delano’s incisive scrutinizing of this desk analogizes it to an operating table par excellence—a site from which imperial ideologues “dissect” colonized Caribbean islands as part of the latter’s activity of total appropriation.

Regarding the feeling of dislocation—as much emotional as geographic—The Museum of the Old Colony meditates on the vicissitudes of Puerto Rico confronting imperialist power, appealing to shared codes and references that orbit around frustration and distress. The insidiousness of such power is embedded in the books on display, which reek with the language of empire. Our Islands and Their People (1899), for example, intended to answer the question: “Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Isle of Pines; the Hawaiian group, the Philippine Islands—embracing territory large enough for an Empire—what of their topography, geography, their agricultural, mineral and other resources?” Likewise, a children’s volume, Our Little Porto Rican Cousin (1902) asks: “The beautiful island of Porto Rico lies, as you will see by looking at the map, near that great open doorway to North America and the United States which we call the Gulf of Mexico. Very near it looks, does it not?” The emphasis in both texts on the geographic richness and geopolitical proximity to the North American continent reveals the deployment of complex tools of cultural domination as pillars of the 19th-century U.S. doctrine of Manifest Destiny.

The presence in Delano’s exhibition of other (historically) colonized territories in the Caribbean, such as Cuba, and those in the Pacific like Hawai’i and the Philippines, points to the respective colonial experiences of these regions. The artist highlights the tragedy of his own homeland but without disregarding the history it shares with other countries of the Global South. One instance of this connection emerged for me, as a Cuban, when looking at the installation’s images of the red, white, and blue Puerto Rican flag. Because most of the photographs in the exhibition are black and white, at first glance I mistook the Puerto Rican flag for the Cuban flag, which has a similar design and the same colors. In black and white, the flags seem conflated—perhaps a symbol of the intimate cultural and historical links between these Caribbean islands—“two wings of one bird”—to quote Rodríguez de Tió’s 1893 famous poem, “To Cuba.” Moreover, I learned, coincidentally, that a black and white version of this mournful patriotic symbol was created by the anonymous artist collective La Puerta as an expression of struggle, resistance, and independence. This was in 2016, in sharp response to the U.S. Congress’ approval of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which put the island’s troubled economy under the control of an external fiscal board.

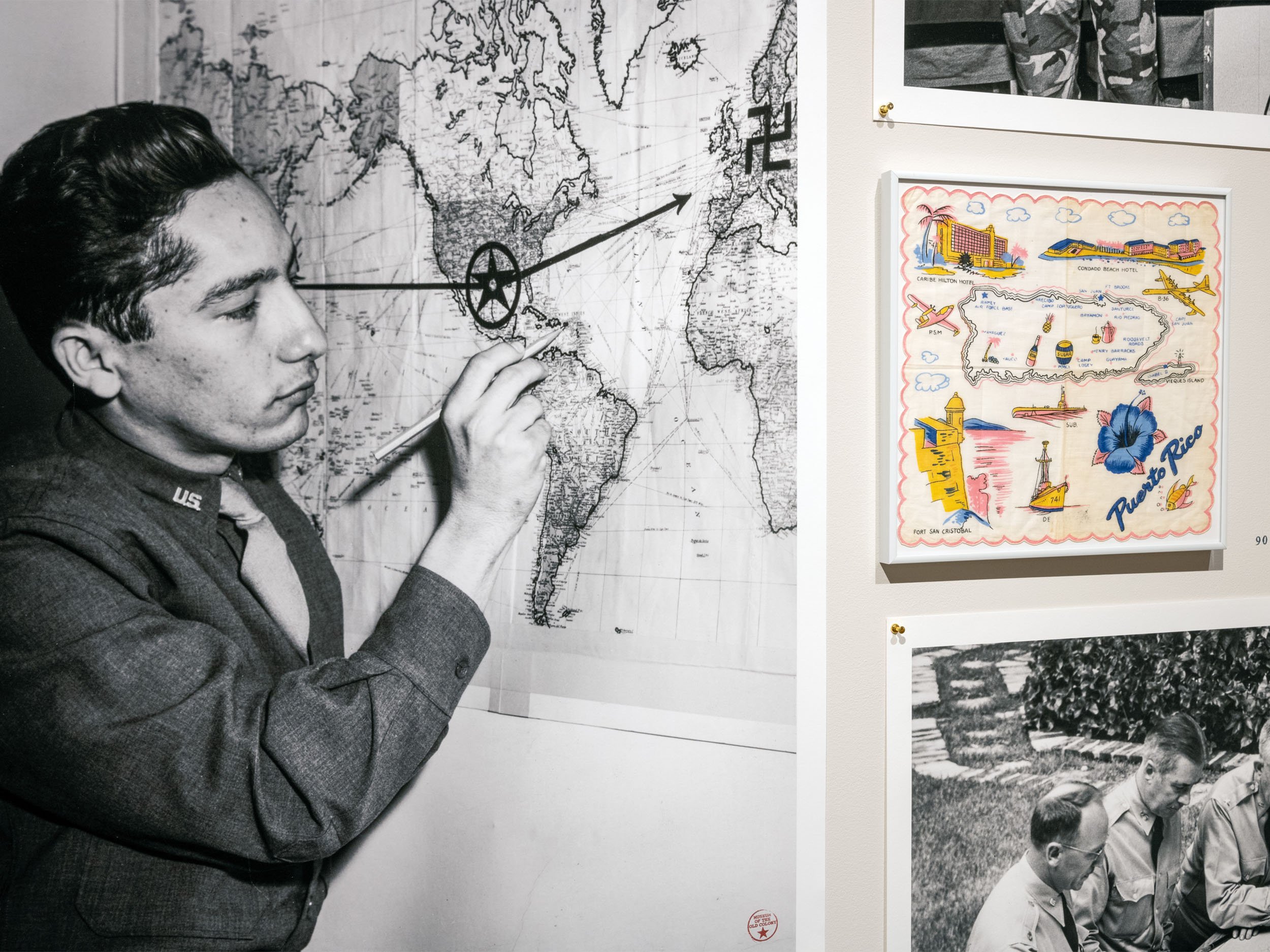

Many are the memorable images of this exhibition. However, one that haunts my mind is “Flores Colón-Colón of Puerto Rico, A U.S. Air Cadet,” a volunteer or draftee in the military during World War II, who points out his country on a map, which indicates Puerto Rico’s strategic usefulness to the U.S. in fighting the fascist regimes then terrorizing Europe. The layers of power dynamics suggested by this photograph oscillate between certainty (as the trainee points with precision) and bewilderment at a presumed recognition (his and ours) of the irony of his position. Rescuing and recontextualizing such distressing images, Delano creates a conceptual installation of aesthetic complexity and emotional weight—one that speaks to the urgent need to confront an uncomfortable past and to face its relevance in the present. With humor, subversiveness, and formal rigor, The Museum of the Old Colony encourages serious contemplation of Puerto Rico by calling attention to the multilayered archives of visual culture that invite a critical rethinking of this Caribbean island.

—

Notes

¹ Lola Rodríguez de Tió, Mi libro de Cuba (La Habana: Imprenta la Moderna, 1893).

² See https://www.jmu.edu/dukehallgallery/exhibitions-21-22/pablo-delano.shtml.

³ Laura Katzman, ed., The Museum of the Old Colony: An Art Installation by Pablo Delano (Harrisonburg: Duke Hall Gallery of Fine Art/JMU in association with University of Virginia Press). https://www.upress.virginia.edu/title/5885/.

⁴ For example, as noted by other scholars, the racial dimension of the installation was emphasized in the JMU venue in Harrisonburg, given the troubling “Jim Crow” racial history of this southern city in the former Confederate state of Virginia. In the New York University venue, images related to the Puerto Rican diaspora were included. See essays in Katzman, ed., The Museum of the Old Colony, 9, 28, and 43.

⁵ In his latest exhibition, curated by Amanda Guzmán, Delano employs assemblage in even more destabilizing ways. For example, in the piece “The crossroads/La encrucijada,” the Santería necklaces or elekes are now at the base of the orisha known as Eleguá, who appears as a tutelary and floating figure in a photograph taken by a Mennonite missionary. It depicts an anonymous traveler who has stopped his American-made car in search of his way through a Caribbean labyrinth populated by palm trees and a sugar plantation in the distance. Delano acknowledges that Eleguá is understood as the “Lord of the Crossroads,” but is also the trickster that this African deity incarnates. Delano too acts as a kind of trickster who questions which road the traveler (and by extension the viewer) should take.

⁶ Katzman, “Puerto Rico in the ‘American Century’: Reflections on Pablo Delano’s The Museum of the Old Colony,” in The Museum of the Old Colony, 29.

⁷ Yomaira C. Figueroa-Vásquez, Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2020), xxviii-xx.

Elizabeth Mirabal is an award-winning writer from Havana, Cuba. She is currently a doctoral student in the Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese at the University of Virginia. Her writing, which encompasses fiction and non-fiction, has been dedicated to rescuing exiled Cuban writers who have been banished from the literary and cultural history of their country. She co-authored two books about Guillermo Cabrera Infante: Sobre los pasos del cronista, which won the 2009 UNEAC Essay Award and Cuban Literary Criticism Award, and Buscando a Caín (2012). She also co-authored Hablar de Guillermo Rosales (2013); Tiempo de escuchar (2011); and Chakras: Historias de la Cuba dispersa (2014). Mirabal is the author of two novels: La isla de las mujeres tristes (2014), which won the Ibero-American Verbum Award, and La belleza de la inutilidad (2020). Her most recent book is Herbarium (2021). For a complete list of her publications, see https://www.elizabethmirabal.com/bio.html.