Dominican Artists Model Liberation at Centro León: Review

Para leer una versión en español, haz clic aquí.

If this exhibition were to have a title, it would surely incorporate the word liberation. The Concurso de Arte León Jimenes is an annual open call that commissions twenty artists to create new work for an exhibition in Santiago de los Caballeros, República Dominicana. Of the artists included in this year’s edition, some reside on the island and others are of the diaspora, and each proposes a project that relates to the current realities of the nation. This year, the artists position a vision that elicits urgency, reformulates official narratives, and poetically encourages critical reflection in the face of great uncertainty. It is a brave presentation of diverse works in the context of a conservative society, where social norms are often fixed and confining, reflecting centuries of colonial trauma.

Many of the artists reflect on how public memory is formed, how archives have historically shaped history, and how information is skewed or erased to the benefit of existing power structures. Blending journalism, public inquiry, archival research, and participation, Lizania Cruz’s 2020 project Se buscan testigos! [Seeking Witnesses!] is one of the first artworks you experience upon entering the exhibition. For this project, Cruz collects public opinions on how the Dominican racial imaginary has been constructed, gathering information to contribute to a public archive. After installing ads on the side of the road and in newspaper classifieds, Cruz received Whatsapp messages from strangers, responding to her prompts, which vary from “Volvería usted a vivir en una isla sin frontera?” [Would you go back to living on an island without borders?] to “¿Qué sabe usted sobre las personas esclavizadas en la República Dominicana?” [What do you know about enslaved people of the Dominican Republic?]. The collected responses are, for the most part, quite conservative, with members of the public emphasizing false distinctions between Dominicans and Haitians, or negating black identity as part of the Dominican racial imaginary. Some answers stand out, like one in Haitian Creole, accusing the artist of being involved with an NGO promoting propaganda, and another voice note, in Spanish, reprimanding the artist for not respecting anyone’s rules, “como todos los Haitianos” [like all Haitians]. Cruz’s archive tugs at the frays of a prejudiced belief system and reveals how popular Dominican identity has been constructed in direct opposition to Haiti and Blackness. Se buscan testigos! encourages a reframing of dominant historical “truths” by posing questions that engage the public in discussion and embed them within necessary archival processes.

Monuments often function as extensions of public archives, and are certainly centerpieces of a visual repertoire of symbols that can stand for freedom, the nation state, and other supposed “pillars” of democratic society. Joiri Minaya’s Encubrimiento de la estatua de Cristóbal Colón en el Parque Colón, Santo Domingo, RD [Covering of the Christopher Columbus statue in Columbus Park, Santo Domingo, RD] (2020), is a proposal in which the altered public monument represents a hegemonic narrative that needs to be undone. By proposing to cover a statue with Cacique Anacaona exalting Columbus at his feet––using colorful fabric displaying indigenous plants used in resistance training––Minaya’s work refuses to venerate the patriarchal authority of colonial leaders, pointing instead to their brutal histories of extraction and violence. Alongside postcards of the proposed artwork with renderings drawn up in Photoshop, El Centro León has displayed official letters between the arts center and other city officials in Santo Domingo, petitioning for a permit to show the work as an intervention in a public context, as originally intended by the artist. They received no response. A proxy of the sculpture sits in the exhibition space instead. After the exhibition opened, Minaya performed an independent action and wrapped her remaining textiles around the actual sculpture in Santo Domingo. This action prompted hundreds of comments on Minaya’s Instagram, thanking the artist for a brave intervention, spurring new critical thought in an urgent moment, and others accusing her of vandalizing and breaking Law 318, which concerns national cultural patrimony. It is worth noting how evocations of nationalism are used as convenient justification for artistic censorship.

Two other works in the exhibition seem to compliment each other in their dissimilarity. José Morbán’s Monte Grande/Paramnesia (2020) questions dominant historical narratives about the Batallón Africano––a group of free black men who fought for independence from Spain in the early 1800s, and examines its intentional exclusions from historical memory. Ernesto Rivera’s Ensayo [Essay] (2020), in turn, questions the concept of the archive itself and its inherent biases. In both projects, the public is presented with constellations of information and contact: Rivera’s perforations in the wall represent real-time fragments of moments past (that viewers are meant to actively engage with), while Morbán’s delicate works on paper present historical information recomposed by the artist. Both projects use abstraction to underscore the ephemerality of exchange and of memory, and gesture towards the unseen.

Abstraction is not the pervasive language of the exhibition, but its subtlety speaks volumes. This is especially true in Charlie Quezada’s All inclusive [Todo incluido] (2020), where minimal abstract sculptures point to the waste and precarity of tourism projects that plague the Dominican Republic as well as other Caribbean states. Often overzealously funded (by international interests like the IMF and the World Bank) and then abandoned, many foreign-owned tourism development projects––all-inclusive hotels, casinos, nightclubs, restaurants, etc.––remain as physical architectures of waste and material decay on the island. In the installation, plastic buoys that would ordinarily separate lanes in a swimming pool hang ominously from floor to ceiling. A plastic awning falls in tatters, partially covering a painting in shade. A chain link fence mimics the ascending waves currents of the sea. The work questions the origins of these materials, and how they end up where they end up, as physical remnants of misguided and hollow dreams.

Melissa Llamo’s Hoy mi cuerpo desapareció [Today my body disappeared] (2020) is a multimedia installation that mimics the experience felt in a concho––a shared cab, popular transportation in the D.R. The work is compelling as it includes video from the experience within the car, where we see strangers entering and exiting the vehicle, wearing face masks, listening to headphones, commuting in close proximity, yet somehow still distanced from each other. The video can be viewed from the inside of the vehicle looking out as well, and the installation includes two car doors that stand upright and frame the scenes. It is a reflection on space, interiority, proximity, intimacy, and how the self is perceived and affected by these contexts. On a wall nearby, monochromatic blue prints of human figures lounge and sit in different positions, like ephemeral ghosts floating in space. Llamo’s installation reflects what many other artists in the exhibition seem to delineate in their work: an ideology of expansive self––beyond the physical and mental confines we impose on ourselves and those around us. Ephemerality and empathy are corresponding features.

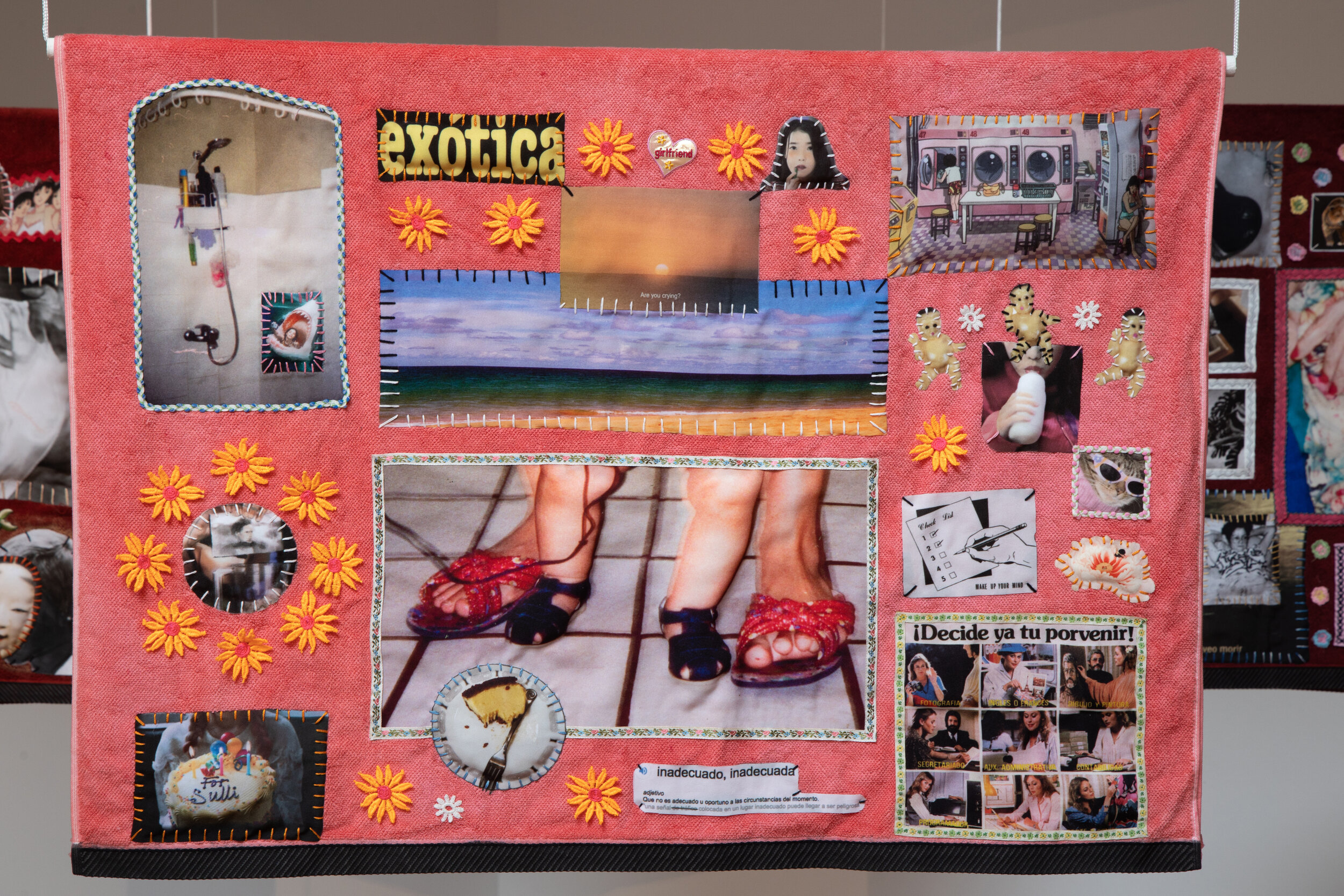

Some of the most salient works in the exhibition are the ones that address this interiority, much like Andrea Ottenwalder’s installation Yo sé que lo que quieres es ser como tú eres [I know that what you want is to be who you are] (2020). It consists of a series of textile collages hung from the ceiling, requiring the viewer to weave between them from front to back, reading like sacred texts or towels hung out to dry in the sun. The collages also look like my screen: bright spheres of notifications and updates, multiple browser windows and tabs, icons cluttering the desktop. They share images of someone’s life, laid out from infancy to adulthood, as if mining all of the social customs and ideologies that have marked them in that journey. Visual symbols of sexuality, childbirth, death, sin, desire, and love, are mixed with unexpected, uncanny elements that punctuate the shades of pink with uneasiness.

Mirar adentro [Look inwards], (2020), an audiovisual installation by Mc.kornin Salcedo, is set within the context of an interior garden space drenched in natural light, and the forms that make up the installation look organic yet foreign, like the smooth, sensuous lines of a cyborg or an Apple product. It is a psychological garden, as the installation attempts to map common psychological conditions that plague the human mind: stress, anxiety, depression, and panic as users strap on headgear. In turn, the installation produces audiovisual sensations meant to address the diagnosed affliction. In this garden space charged with natural energy, humans wear technology that mimics natural processes of healing: introspection, awareness of sound, light, etc. It feels like a startlingly contemporary update of Lygia Clark’s Sensorial Masks of 1967, healing but also somehow menacing.

Puentes [Bridges] (2020), an immersive installation by El Editor Cuir y Johan Mijail, includes curtains of video featuring people kissing, sleeping, lounging, talking, and childhood family photos. There are fragments of gender-non-conforming clothes and makeup, and moments of intimacy and care. Sandwiched between two sheer curtains are two suspended circular mirrors, which the public is invited to engage with. Looking at your reflection in this installation is like looking back at a tunnel of reflections, repeating itself infinitely. There is a formal thread here connecting the visual sensation of expansiveness and interconnectedness between your own image reflected, and those of the people projected onto the surrounding curtains. In this work, a queer subjectivity is positioned as part of a common identity or experience, acknowledging it has always been present and will continue to expand into many possible futures.

The last work of the exhibition I experienced was Awelmy Sosa’s La puerta [The Door] (2020). Outside of the building, in a blistering sun, I encountered a giant wooden door, about two or three times the size of a human being. I knew the work was meant to be a performance (one I would regretfully miss out on), in which the artist painstakingly uses a string of keys to unlock each of the door’s 44 locks, before it comes crashing down like a hammer. The door itself lacks a handle, and the task feels impossible, but eventually, the door falls fast and hard. It is a reminder of all of the giant locked doors and other seemingly insurmountable obstacles. With enough force, time, and tenacity, the door can be torn down. It has to be torn down. The works in the exhibition model this capacity and potential for liberation.

To take a virtual tour of the exhibition, click here.

Alex Santana is a contemporary art scholar, criticism writer, and curator with an interest in conceptual, political, participatory art and curatorial studies. Originally from Newark, NJ, she is a child of immigrants from Spain and the Dominican Republic, and is deeply committed to social equity and access, most especially in the arts. She has held research positions at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington DC), the Newcomb Art Museum (New Orleans, LA), and Mana Contemporary (Jersey City, NJ). In 2018, she curated the exhibition Morir Soñando at Knockdown Center (Queens, NY), and since then has collaborated with artists and curators on other independent projects, including a DIY summer lecture series, Artists on Artists.