What is Latinx? See El Museo’s La Trienal for the Answer

Several years ago, I tried to convince my boss at the time that El Museo del Barrio was a museum of American art. He took me too literally and rejected the notion but I think the point bears repeating in light of its most recent exhibition, which opened March 22, 2021, Estamos Bien: La Trienal 20/21. As in past editions of this exhibition, the vast majority of the artists were born in the United States and all of them have made a life here. As longtime residents, they make work about the American experience. Their work should be in collections of American art and be included in exhibitions of contemporary American art.

La Trienal is the most recent iteration of El Museo’s crucial periodic exhibition devoted exclusively to the most recent art made by US Latinx artists. Conceived and first executed in the late 1990s (under the title The [S] Files), these exhibitions were originally intended to be organized yearly and would focus on art by local artists of Latin American and Caribbean heritage living and working in the NYC region. This series of shows served as a response to the invisibility of Latinx artists in exhibitions of contemporary art in New York City and continue to be a response to the invisibilization of US Latinx artists in other periodic exhibitions such as the Whitney Biennial, MoMA/PS1’s Greater New York exhibitions, and the New Museum’s triennials.¹ El Museo’s exhibitions are a testament to the significance of the museum in the landscape of contemporary art, having launched the careers of many artists and expanded audiences for contemporary art by Latinx artists. As such, these exhibitions also cement the position of El Museo as a creator, developer, and supporter of US Latinx art and art history. To date, over 300 artists have been included in these exhibitions. Among these, many have continued to find success in other spaces, have won prestigious grants, fellowships, and residencies, and are now teaching new generations of artists at some of the most important art schools in the country. For the vast majority, El Museo signified their first opportunity to exhibit their work in an institution of some scale, with a significant history of attention to this work.

In a new twist, this year’s exhibition takes a look at the national scene, inviting artists working in California, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, and Texas, and of course, our own beloved New York. The exhibition is organized by El Museo's curatorial team of Rodrigo Moura and Susanna Temkin, with artist and guest curator Elia Alba. Every artist in this exhibition is worth concerted attention and consideration. However, in the interest of time, I will focus on a handful of artists who address intertwined themes of presence, place, and memory. By focusing on the works of Groana Meléndez, ektor garcia, Xime Izquierdo Ugaz, Dionis Ortiz, Edra Soto and Joey Terrill, we can explore how concepts of home, environment, meaningful objects, and the presence of a body are presented in order to relay corporeality, place, and memory. All are ways in which artists and their subjects claim space, act as witnesses, and expand the discourse of the American experience.

Edra Soto’s Graft, 2021 (fig. 1), is one of a handful of works that were commissioned especially for the exhibition. In this case, the work has been created to fit between and on the windows of El Museo’s newly opened gallery on the south side of the building (fig. 1). The work’s form is based on the patterns of the quiebrasoles (literally, sun breakers) and rejas or breezeblocks and window grates that are a celebrated and crucial part of Caribbean architecture. For the artist, the work begins first with research and in this particular case, “questioning aspects of vernacular architecture, in relation to colonial architecture in Puerto Rico.”² Edra notes that the pedagogy of architecture in Puerto Rico often emphasizes a connection to Spanish architecture, but neglects to acknowledge Taíno and African influences. Many of the design forms of these blocks recall African symbols that have been the inspiration for fabrics, logos, and pottery and that have also been incorporated into architectural features. Edra has added to the nuance of these forms by creating a ghostly effect on the actual windows of El Museo with an opaque mylar in the same pattern. In addition, the artist has incorporated small mirrors into the piece, at eye level, so that we not only witness meaningful forms, but also, in a sense, to partake in their existence and become part of the forms, as well as their past and present lives. A closer inspection reveals a small eyehole which we are meant to look through and we are rewarded with various scenes of landscapes of Puerto Rico. Together, the forms and the photographs bring together architectural signs and the land in which they are cradled.

Like Edra Soto’s Graft, Dionis Ortiz’s work, Let there be light, 2021 (fig. 2), was created specifically for the gallery in which it is displayed, and it is truly majestic. Using plastic floor tiles as bearers of memory, the work covers a large portion of the floor of the first gallery in the exhibition. Anyone who has lived in old New York buildings has experienced a kitchen or bathroom floor layered with decades of adhesive floor tiles. Much cheaper than ceramic, they are the flooring of choice for cost-cutting landlords, or families of limited means hoping to improve their interiors. Dionis literally “mines” these tiles, treating them as sites of excavation and memory in which family moments have been recorded in the physical surface of the work, as when his father taught him how to install such tiles. Using four different patterns, the artist creates a new, larger pattern, fabricating a kind of oversized carpet--one perhaps meant to contain a family’s history over many generations. One set of tiles, with a black and white checkered pattern, is deliberately intervened by the artist with blue enamel paint. On this surface, we see the traced gestures of brooms and mops as the floor is being cleaned, recalling the labor his own parents did in order to support the family. These motions, preserved forever in the surface of the tile, signal the presence of all those that have worked to make a new and better life, as witnessed through the humble surface of the vinyl flooring.

In the same space as Dionis’s floor piece are three paintings by Joey Terrill, an artist with over four decades of work. Terill was deeply influenced by the Pop Art movement as it developed in LA and by the gay underground scene that allowed him to feel part of a community, early on in his youth. These two worlds collide in colorful paintings that pose the commercial products that punctuate contemporary life against a colorful woven tablecloth (that brings Mexico to mind) with partially nude male figures in the background. The title of one painting makes direct reference to a 1956 pop art collage of American magazine images by the British artist Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? Joey’s painting reworks the title as Just what is it that makes today’s homos so different, so appealing? (fig. 3). The artist has replaced Hamilton’s buff, mostly naked male model with two male figures—one brown, one black—making love in the background. In the foreground is a still life worthy of a seventeenth century Dutch painting, but loaded with signifiers of a gay Chicano identity in which “American” and “Mexican” are fully blended. Here, we see bottles of Coca Cola and Cholula with Tony the Tiger’s face, Morton salt and Quaker oats, capsules of medication for HIV treatment, and a Magic 8-Ball—all atop a colorful, woven tablecloth that recalls a serape.

![Groana Melendez, Ni de aquí, ni de allá [Neither Here, Nor There], 2005-ongoing; 18 archival pigment inkjet prints.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e540f30394fe70075c1ccd6/1618351049070-NCY5W2PRGCTBSA9HDYSZ/20210311_182317.jpg)

![Groana Melendez, Ni de aquí, ni de allá [Neither Here, Nor There], 2005-ongoing; 18 archival pigment inkjet prints.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e540f30394fe70075c1ccd6/1618351282300-KN4KAWSNXDSUJR13IAJF/20210311_182336.jpg)

There are two series of portrait photographs by two women in the exhibition that address home, presence, and representation in various ways. Both Xime Izquierdo and Groana Meléndez approach their work specifically around their subjects, focusing on the surroundings and the physical presence of those they portray. Groana’s images, Neither Here Nor There/Ni aquí ni allá, 2005-ongoing (fig. 4), consist of family portraits, illustrating the double-consciousness, the neither here nor there in-betweenness, of a family divided between two countries: the Dominican Republic and the United States. In her photos, the scenes of dining rooms, formal living rooms, gardens, a bathroom, front patios, a favorite chair--these spaces all become like an extension of their sitters. Places of reflection and comfort, safety and ease, in the artist’s portraits the spaces are like collaborations in the presentation of her family. Caught in solitary moments--reading, sitting under the hairdryer, occasionally with another family member, the artist shows us the universal experience of people occupying their own spaces, presented in an uncomplicated yet powerful way.

In a similar gesture, Xime Izquierdo Ugaz’s series, Sé que fue así, porque estuve allí/I know it was so, I was there, 2017-ongoing (fig. 5), underscores the uniqueness of each subject not only through the image created but also through the frame that they use for each photo. The artist calls this photographic project a “virtual archive.” On their website, it functions as a kind of exuberant inventory of ordinary-extraordinary queer people rejecting gender and body norms to embrace all of their fluid and glorious difference. Paired with spoken testimonials, the archive allows a trove of images and voices of LGBTQ and non-binary people of color to tell stories that broaden the narrative of the American experience. The sitters were photographed in various cities, including Boston, El Carmen (a town with a strong African presence in Perú), Lima, New York, Miami and Washington, DC, as the artist made up their broader “family” through those with whom they felt a strong connection. Like in Groana’s photos, the sitters in Xime’s pictures are sometimes in their own spaces or other locations of comfort, looking out their window, playing a piano, sitting at the beach, modeling a favorite outfit. Each frame is carefully selected by the artist to underscore the close relationship they feel to each sitter. Through these frames and how the work is installed, we can interpret the work as a kind of “familial collage,” like one might see in the hallway of someone’s home. The intimacy between photographer and sitter is evident in the comfort that is evoked in the images and the way they are presented to us as viewers.

Another rumination on home, place, and presence can be seen in the large, double-sided painting and a series of smaller collage works by Candida Alvarez. Estoy bien, from the Air Paintings series, (2017; fig. 6), was painted in the wake of Hurricane María and with the Puerto Rican people and the island’s landscape in mind. Perhaps even more appropriate, the title of Candida’s painting inspired the title of the entire exhibition, a powerful claim given the year 2020. In the collages, we see and feel the chaos of the hurricane as it moves objects through garden walls, across flattened greenery and we are left to wonder which way is up. The phrase “Estoy bien” appears in the painting in a speech bubble, surrounded by little white flowers on a pink and green background. Shapes that allude to roofs and walls are highlighted by dripped paint that recalls the spray enameled walls of city streets. Painted on PVC mesh, the entire work has the feel of a textile, as though painting and tapestry are brought together here, like two sides of a coin. The question that immediately follows “Estoy bien” is painted into the work also: “are you ok?” These are the first phrases of any familial phone conversation held in the wake of a crisis. Here, they are presented as though being spoken in the immediate aftermath, perhaps from one neighbor to another, over what remains of the garden wall. The spirit of human resilience is perhaps most present in this work, in which oddly-shaped forms and partially broken shapes are nonetheless painted in bright and happy pink hues. Even when the world is falling apart, “estoy bien” is the phrase we all hang on to, hoping to make it so.

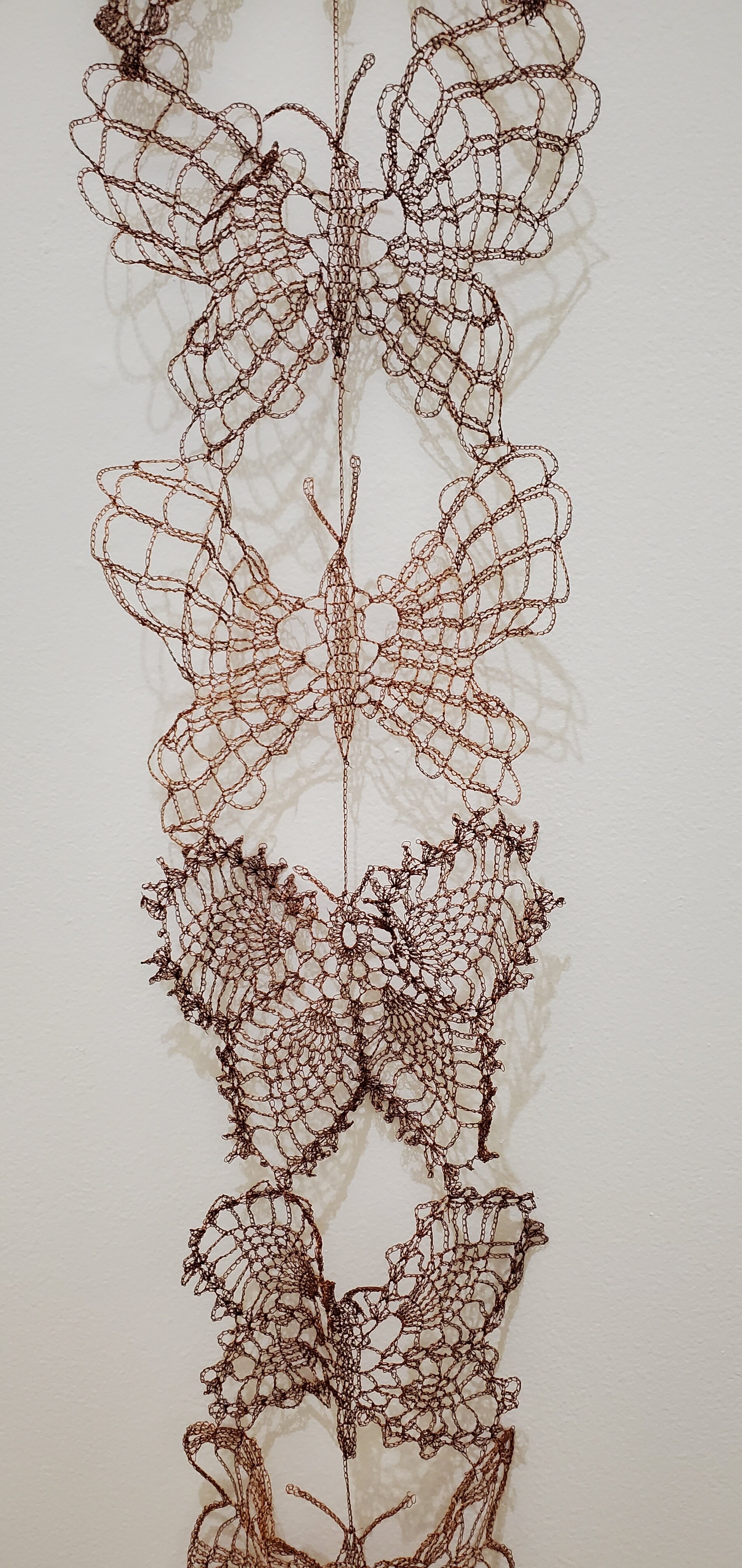

A final work that resonates with our themes of place and memory, public and private, is seen in the collection of works by ektor garcia. There are two large crocheted works, including a series of butterflies fashioned from copper wire. This work expands on what the artist has addressed as a contradiction between handmade craft (often understood as employing soft materials and the domain of women), and the labor and potential pain involved in a sculptural, hand-made process. How does one crochet with wire? The artist has remarked on his choice of media: “I submit to materials, but also try to dominate them. I am in their service, constantly obeying their behavior, but I’m also forcing them to misbehave and to work for me. There is much pain and pleasure in the work I do. At times I feel I can’t have one without the other.” Mariposa (butterfly) is a term sometimes used to describe a man who may not be perceived as “masculine.” Through ektor’s work, we might see the copper wire as a kind of armor, a protective outer layer for the delicate forms of the ornate wings. Adding to the sense of place, domesticity and memory is a work placed on the floor, made from glazed stoneware, a red light bulb and crocheted leather titled I can’t afford to live here, I can’t afford to die here, (2020). Vaguely reminiscent of both a pendant lamp and a large vase, the thick, black surface contradicts a strictly decorative reading. The other works in the grouping are made from leather and steel, one piece recalling a mid-century abstract painting, the other a large hanging work that centers crochet. The artist offers thoughts on the contradictions and prejudices of the art historical canon, that favors a particular kind of masculine work (abstract painting) and invisibilizes the feminist perspective (fiber arts and craft). Making crochet work in the scale of monumental sculpture and painting, the artist amplifies the idea behind the personal as political, the hand-made as sculptural, and leaves questions of gendered materials up to the viewer. This last element is particularly important to the artist, he notes: “In my dream world, I would love for the viewer to learn something about themselves in my work. I purposefully never finish or complete a piece. I want the viewers to complete it for themselves. I provide more questions rather than answers.”

These beautiful thoughts are relevant to the other works in the exhibition, which are all deeply rewarding, powerful, carefully considered and exquisitely made. While the art market for Latinx art continues to be largely invisible, I live with hope that some of these works will find homes through museum exhibitions and acquisitions, and will find their way into other significant public and private collections of American and international art. As artists exploring the lived experience of life in the US, their work serves to expand our understanding of the history of American art and to remind us that El Museo del Barrio has been a key institution in creating the knowledge concerning this field.

On display and open to the public between March 13, 2021 to September 26, 2021, El Museo del Barrio presents ESTAMOS BIEN – LA TRIENAL 20/21, the museum’s first national large-scale survey of Latinx contemporary art featuring more than 40 artists from across the United States and Puerto Rico. For more information, visit elmuseo.org

Footnotes

¹The most recent Whitney Biennial may be one exception, featuring the most USLatinx artists seen thus far. There remains a significant invisibilization of Latinx artists in museum collections, exhibitions and gallery representation.

²Scott Indrisek and Edra Soto, interview, Foundwork [https://foundwork.art/dialogues/edra-soto].

³Sean Santiago and ektor garcia, “The artist ektor garcia submits to never being satisfied,” interview, PIN-UP, [https://pinupmagazine.org/articles/artist-ektor-garcia-pinup-studio-visit].

Rocío Aranda-Alvarado is a program officer in Creativity and Free Expression at the Ford Foundation. She is an art historian and curator. She joined Ford in 2018 after serving as curator at El Museo del Barrio for nearly a decade. In that role, she presented visual arts exhibitions and programming that reflected the history and culture of El Barrio as well as the greater Latinx and Latin American diaspora, including Antonio Lopez: Future, Funk, Fashion and PRESENTE: The Young Lords in New York. Prior to that, she was the curator at the Jersey City Museum for nearly a decade, where she organized exhibitions such as Tropicalisms: Subversions of Paradise, Industrial Strength: Precisionism and New Jersey and solo exhibitions on the work of Chakaia Booker and Raphael Montanez Ortiz. Concurrent to her work in museums, Rocío taught as an adjunct professor; consulted and curated independently on Latinx and Latin American art and culture; and published and advised, in both a scholarly and curatorial capacity. She earned her PhD in art history from the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. Rocío taught for several years at The City College of the City University of New York, where she developed a course on US Latinx art history for the Art Department. In her work at the Ford Foundation, Rocío has organized a number of regional meetings focusing on the lack of visibility for US Latinx artists in the broader museum field and in the history of American Art.