“We Are Here”: Introduction

I’m the founder and editor-in-chief of the well-loved indie art website Gallery Gurls, which celebrates womxn, BIPOC, and QTPOC, yet I have zero professional experience in the art world. I’ve never worked for a top gallery or an important museum, and I don’t have a fancy graduate degree in art history or visual arts criticism. I’m a former fashion show producer and photo editor with an insatiable appetite for contemporary art and a voice that is unorthodox, frank, and intentionally not rooted in academia. My mission with Gallery Gurls, since founding it in 2012, was straightforward. As a Black woman, I want to solely cover womxn, BIPOC, and QTPOC in the art world in the most accessible way possible, with curiosity and Wi-Fi being all that is required.

My attraction to fashion and art is organic and pure, and started very early. Growing up as a poor, first-generation Afro-Dominican, artsy girl in Queens, it was just the three of us—my Dominican single mom, my younger brother, and myself. My mom cherished literacy, so the only abundance in our household came in the form of books. There were wall-to-wall shelves filled with trashy novels, historical fiction, artist monographs, and photography books, and I read them all incessantly. When I was twelve, my world was forever changed when my mom gifted me a subscription to Sassy magazine, a budding feminist’s dream. I’m an eighties baby and nineties teen, so my universe was shaped by the hours spent locked in my room plastered with Spice Girls posters, poring over issues of Vibe, The Source, Elle, and Vogue, and devouring MTV, VH1, BET, and E! twenty-four seven.

I visited a museum for the first time in 1997 at age seventeen to see a Gianni Versace exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Versace, who was tragically killed that year, was my favorite fashion icon and this was my chance to see his dazzling designs up close. My high school fashion teacher—a Colombian Nina García doppelgänger—encouraged me to see art in Manhattan and keep a journal that detailed how I felt about it. In many ways, this was a precursor to my blogging and writing that would happen a little over a decade later. So I kept observing, consuming, discovering, and interacting with art, and eventually I got it into my head I would pursue a creative career and apply to art school.

During my four years at Parsons School of Design, studying fashion and marketing among mostly rich white kids, my art education primarily focused on dead white men—Monet, Manet, Seurat, Picasso, Man Ray, de Chirico, Ernst, and Warhol. One rare exception was a surrealist women artists class I took my junior year, where I was introduced to Claude Cahun, Leonor Fini, Lee Miller, and Meret Oppenheim, and where I first fell in love with Frida Kahlo. While the class was unforgettable, it failed to include any Black womxn. I soaked all this up while habitually visiting all the major New York museums—the Met, Guggenheim, Whitney, MoMA, and the New Museum—especially once I discovered suggested admission and weekly free nights. I yearned for Blackness in art and fashion, but I wasn’t learning much about famous BIPOC artists or fashion designers in class or finding them on museum walls. It was magazines like Trace (where I was an intern), Honey, and Suede (which would come years later) that fed me that Black invigorating creativity I desperately craved.

As a twentysomething in the 2000s, it was exhibits like Kara Walker’s 2007 solo show at the Whitney that gripped me. I’m pretty sure that was the first time I ever saw a solo exhibit by a Black female artist. Seeing a Basquiat retrospective in 2005 at the Brooklyn Museum had that same visceral effect, too. By 2009, Kehinde Wiley was already a king, an artist whose work shook me to my core, so going to see his Black Light exhibit at Deitch Projects was an unmissable event. Over the years, my attachment to art grew deeper and deeper, and no one was going to make me feel like an Afro-Latinx girl from a low-income working-class background didn’t belong in culturally privileged spaces. Even during all those years when you could count on one hand how few BIPOC were present at packed art openings in Chelsea. I simply wouldn’t allow it.

By 2012, it was time to write about art. I had seen enough, lived enough, traveled enough, and had formed an aesthetic. I’d gazed at Klimts at the Belvedere in Vienna, mentally wrestled with Francis Bacon’s dark canvases at El Prado in Madrid, and swooned over Dawoud Bey’s images of Harlem at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Most of all, I loved vibrant, figurative work by Black and Brown artists—that’s what resonated with me. That’s what Gallery Gurls was going to be about. I abandoned my personal blog that I started in my late twenties in 2010, my tiny little corner of the Internet dedicated to musings on contemporary art, fashion, and pop culture. Instagram was crucial at this point; it became a major research tool for finding new artists both globally and locally in New York City. So I roamed Instagram, at first seeing artists’ work on a tiny screen and then seeking it out IRL at a gallery, museum, or in their studio. Whatever their work made me feel in my gut, I spit out onto a published post. My words were raw and pure; I didn’t overthink it. But the art world wasn’t just being shaped by artists, it was also being shaped by independent curators, cultural producers, and art entrepreneurs who were young and BIPOC just like me. It was essential to capture them, too.

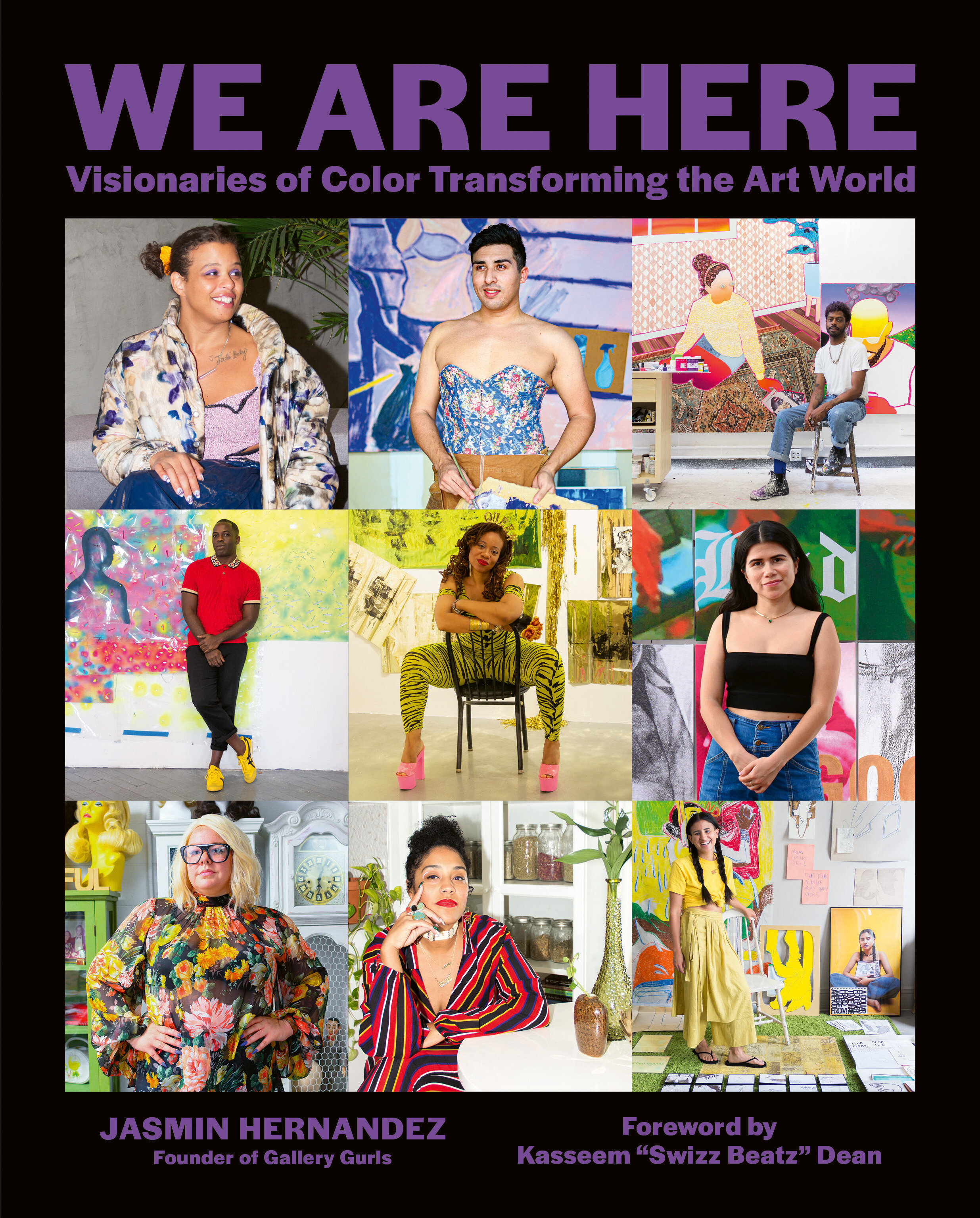

We Are Here: Visionaries of Color Transforming the Art World is a graduation of sorts, both for myself and for many of the fifty featured subjects. Many of us met through social media in the early 2010s, followed each other online, and formed relationships IRL. I went to their openings, featured them on Gallery Gurls, and wrote about their work for big mainstream publications.

We attended each other’s panels or spoke on panels together, discussing topics like equity, access, and representation in the art world. We collaborated and supported one another. We all came up together. I’m a blogger and writer, and now debut author. They’ve become agents of cultural change through their art and activism. Everyone grinded, and this book is the evidence.

I selected an impressive array of BIPOC and QTPOC artists and art influencers to be a part of We Are Here. They are from all over the world and are mostly based in New York and Los Angeles. A multitude of stories are told here, since there is no single, definitive path to making it in the art world. Some are PhD candidates or have dual BFA and MFA degrees, others have a single degree, are college dropouts, or attended zero college at all. This is an intergenerational group of artists and creatives, from baby boomers to millennials, including established icons, unsung heroes, rising stars, and those on the come up. They are painters, photographers, sculptors, installation artists, collagists, performance artists, filmmakers, multidisciplinary artists, digital artists, fashion illustrators, and so on. Including emerging curators, gallerists, and art entrepreneurs was also vital; while artists make impactful art, these influencers get their art out into the world.

My eye is always seeking out intriguing art in both typical and unexpected places. I looked beyond prominent artists repped by big galleries and into other worlds, like the ballroom community and QTPOC nightlife. These are worlds that have shaped me since I was a teen in the nineties in New York City, immersed in QTPOC spaces, going to voguing balls, legendary nightclubs, and kiki-ing at the Christopher Street Piers. This book would not be complete without exhibiting this cultural influence, without showcasing a spectrum of QTPOC folx.

Lastly, it was paramount for me that this book prioritized BIWOC, specifically Black womxn. There was no question about it, and we are the most represented in this book. It’s a love letter to us, to Black female artists and creatives. I wanted to see us, to celebrate us. Despite all the societal hoops of fire Black womxn have to jump through—on top of being othered, despised, dismissed, undervalued, and having our culture appropriated—Black womxn continue to innovate and drive creativity.

The artists and art influencers in the pages of this book have set the tone for this new decade. In each interview, these subjects lay bare their emotions, ambitions, and desires. Their language and purpose is very clear—to make the art world more equitable across the entire art ecosystem. Which means more Black and Brown artists on museum walls and in gallery spaces, amplifying a QTPOC narrative, taking institutional decision-making positions to enact change, hiring BIPOC curators to create BIPOC driven exhibitions, commissioning BIPOC art writers with great writing opportunities, hiring BIPOC editors to edit our stories, building up strong networks of BIPOC art collectors, and making cultural spaces more welcoming and less intimidating for Black and Brown audiences to enjoy art.

Mainstream and art world media are now paying attention, catching up, and covering BIPOC and QTPOC artists more frequently, but a tangible, collected cultural history is needed. We Are Here is a document of Black and Brown voices in the art world, visualized by a Black woman, with the intention of making visible those who are often erased. We’ve been here, we are here, and we will continue to be here. The hyper-visibility of Black and Brown artists and culture-makers that we’re seeing isn’t a trend. The guard has shifted, and no one, including myself, is asking for permission.

Excerpt from the new book, WE ARE HERE: VISIONARIES OF COLOR TRANSFORMING THE ART WORLD by Jasmin Hernandez, published by Abrams. ©2021 Jasmin Hernandez

Jasmin Hernandez is the Black Latinx founder and editor in chief of Gallery Gurls. Her writing has appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, Paper, Bustle, Elle, The Cut, Artnet, and more. She is the debut author of the forthcoming Abrams title, We Are Here: Visionaries of Color Transforming the Art World, releasing February 2021. She is a native New Yorker born to Dominican parents, based in Harlem, New York City. To learn more follow @gallerygurls.