Threading Bloodlines: Crafting, Dreaming and Searching in HILOS

During my curatorial residency at Latchkey Gallery in the summer of 2021, I curated the exhibition HILOS, a visual dialogue between the works of five emerging Latinx artists addressing the intersecting threads of colonialism, past and present. Each artist studies and references craft traditions, techniques, and objects as tools for examining their relationship to their own ancestral and generational histories. The exhibition is curated for us to engage in face-to-face dialogue with each artist's works. At the same time, we are building upon an already existing conversation between materials, surface and texture—all threading together thoughts on bloodlines, oral history, archival learning, and future dreams.

Before curating HILOS, I had the opportunity to interview Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez, a collaborator, fellow adoptee and artist, for Intervenxions.¹ During our conversations, I grasped onto this recurring idea of proximity; proximity determined through the accessibility to learn and reconnect with our first and biological ancestry in objects, histories, visuals and popular culture of our heritage. This idea continued to pop up in conversations with fellow artists and makers, centering on thoughts of reclamation and generational effects due to colonialism. With reclamation, there is a constant search in connection to pre-colonial history, to history before trauma. For many who identify as Latinx, the visual language of craft and visual traditions serve as an one of many important vehicles (for some, it being the only accessible vehicle) to be able to reach closer to reconnection, in deconstructing and understanding the past and present impact of ongoing colonialism.

Blood Quantum

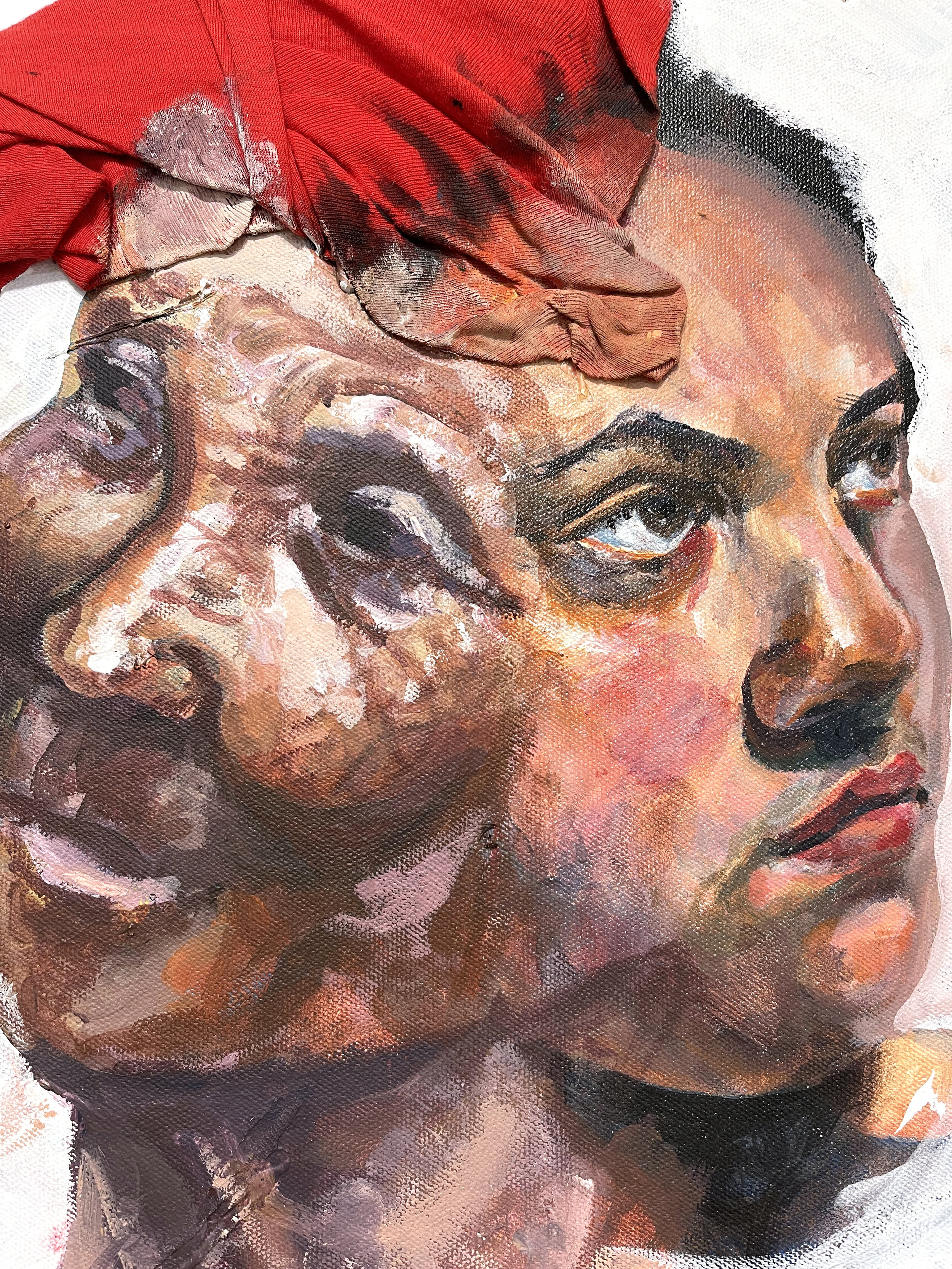

Through a series of four performances, Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez created Limpieza de Sangre, 2015-2016, a collection of sixteen panels, each with intuitive images drawn using the artist's own blood extracted via venipuncture. The works, reminiscent of Spanish Casta Paintings, present ideas and questions around blood quantum,² an ongoing conversation within many Indigenous communities. The panels, arranged like blood slides, examine this conversation through the adoptee lens, questioning the notion of Latinx, Latin American, familial and biological identity, and the definition of bloodline. Displayed opposite, Elvia Carreon’s large-scale painting Familia bloodline, 2018, shows an almost haunting portrait of several generations of her maternal family, using fabrics to visually show the bloodline connection between them. In shaping the fabric organically, the portraits warp, abstracting the images. The idea of connections through the single thread or bloodline become less clear. This makes the connection from one image to the other harder to understand, forcing the viewer to interpret the connection between the figures. In trying to visualize the connection, the viewer can begin to decipher more and more, the eye mimicking the artist's own exploration and analysis of generational connections. In having Carreon’s work opposite Lundberg Torres Sánchez’s, the works engage in an exchange of what blood connection means within different levels of proximity.

Archival and Material Language

Material and object are important in creating an iconography around histories. For many of the artists, the choice of material transforms the work into a personal language. In Community Leisure Jacket, 2019, artist Rosalee Bernabe transforms a familiar object into a historical narrative through the use and treatment of leather patchwork and grapes as a natural dye. The jacket, hung in the gallery as its own body, is a historical exploration of the history of Mexican and Filipinx farmworkers in California between the 1930s and 1970s. They are reminiscent of "farmworker prayers and the immaculate suits cooperatively purchased by migrant workers who took turns wearing them to taxi dance halls." In the piece presented as a figure in space, the context of the work is reconnected to the experiences and lives it embodies, pushing the artwork beyond object and humanizing its history.

For Susan Flores-Melgar and Luis A. Sahagun, material is a connection and an archive of memory.

In Aguila y Sol, 2020, Sahagun alters the idea of comfort and safety in a childhood blanket. In using beading and burning techniques, the cobija San Marcos, an object familiar within Mexican culture, threads together the national imagery of the American flag with the connection to Mexican folklore and nationalism. Flores-Melgar's paintings, Anita, 2019, and Marco como Jesucristo, 2019, use material in a way that is reminiscent of intimacy in home spaces. The use of the hand in the organic shapes of the ceramic frames against the scale of the small intimate paintings become reminiscent of portraiture and images commonly found in Latinx domestic spaces. This transforms the gallery wall and brings a familiar idea home within the space. Like Sahagun, Flores-Melgar uses material to trigger memory and transform it in a way that causes the history of these familiar spaces and objects to be re-examined.

Generational Oral Narratives

The idea of storytelling and oral history can sometimes be the only way to understand generational identity, though the information we receive is curated by the storyteller. Carreon explores intergenerational bonding and intimate conversation as storytelling in her work, often through analyzing gossip or "chisme" culture as a source of information. In the painting Trenzitas y chismes, 2019, Carreon depicts a dinner scene with the women in her family. Embroidered terms reminiscent of nicknames used amongst Latinx families are layered on top. Also incorporated is the use of braided hair and ribbons, an object that is representative of femininity and Womanhood in Latinx cultures and specifically nodding to Indigenous braiding traditions in Mexican culture.

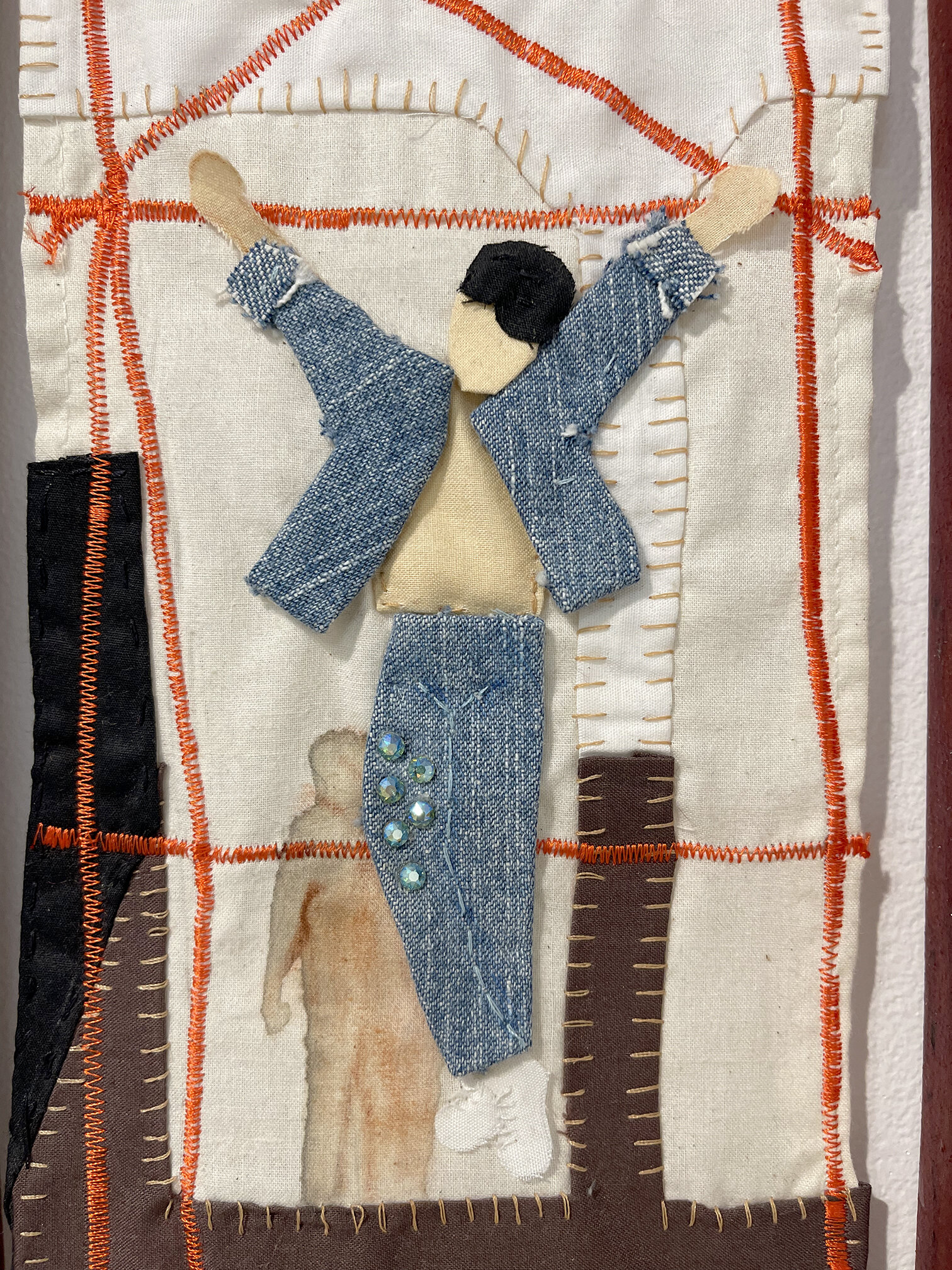

Displayed opposite is the grouping of works by Lundberg Torres Sánchez and Carreon. Centered, Carreon's painting, Abuelita y yo bloodline, 2016, shows the physical blending of she and her grandmother into one entity. Framing Carreon’s work are the two fabric portraits, Morning Ritual, 2021 and Papá, Tío, Violador, 2021 by Lundberg Torres Sánchez. Based on depictions of their adopted and first father, the intimate, delicate works flow into the narrative of Carreon’s piece. In grouping these works, we are presented a narrative of the relationships and proximities to the images we have of family and the narratives that these members represent within our own identity.

Dream Imagination

As an adoptee, common ideas in my relationship to my identity are the dreaming and imagining of what was, what could have been, what could be, and the possibility of multiple futures. For the Latinx artists of Hilos, vision and mysticism surround the same questions when thinking about history and the ongoing effects of colonialism. In Dream Matrix (Sierra del Tigre), 2021, Bernabe uses dreaming as a way to visually reconstruct her mother's childhood home in Jalisco, Mexico, using memory, narrative, and sleep. Framing Bernabe's dream, Sahagun created peticiones in Between Worlds (Petición for restoring life force), 2021 and Mutation of the Spirit (Petición for remapping reality), 2021, using bead work as a symbol of mestizaje and DNA. These beads also become portals so that Sahagun’s "shapeshifting essence (spirit) may travel into other realities in order to acquire different ways of seeing and knowing." In Bernabe and Sahagun's works, there is a sense of dreaming to heal and re-envision, a concept found throughout the works in the exhibition.

For all of the artists, the intersecting threads of colonialism and generational trauma are woven into their present narratives. In the act of making, each artist developed their own language in communicating between their body and the lives of their ancestors. Crafting in connection to histories, narratives, and imaginations became an act of healing through sifting the continual effects of colonialism and its framing of contemporary Latinx identity.

Notes

¹Ortiz Saucedo, Maya. “Adopting Performance: A Conversation with Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez.” The Latinx Project at NYU. 24 June 2021.

²A measure of native status based on social and racial constructs by the United States government as an act of erasing Native American peoples and sustaining white supremacy.

—

HILOS was on view at LatchKey Gallery in New York from July 8th to August 7th, 2021, featuring works by artists Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez, Elvia Carreon, Luis A. Sahagun, Rosalee Bernabe, and Susan Flores-Melgar, and curated by Maya Ortiz Saucedo. The exhibition can be viewed virtually on the LatchKey Gallery website.

Maya Ortiz Saucedo (b. 1996 Chicago,IL) is a curator, researcher and writer based in Brooklyn, NY. Her work engages in the subjects of Contemporary Latinx Art of the US, Latin America and Caribbean; Latinx Art and Artists of the Midwest and Decolonial Theory. She has written for The Latinx Poject at NYU’s publication Intervenxions (Adopting Performance: A Conversation with Benjamin Lundberg Torres Sánchez, 2020) and Digimyths (Notes on Navigating the Colonial Universe, 2021). She recently curated Hilos at LatchKey Gallery in New York. She recieved her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2018. She is currently a graduate student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is recieving her Dual Masters Degree in Art History and Arts Administration and Policy.