The Women of April: An Interview with Lourdes Bernard

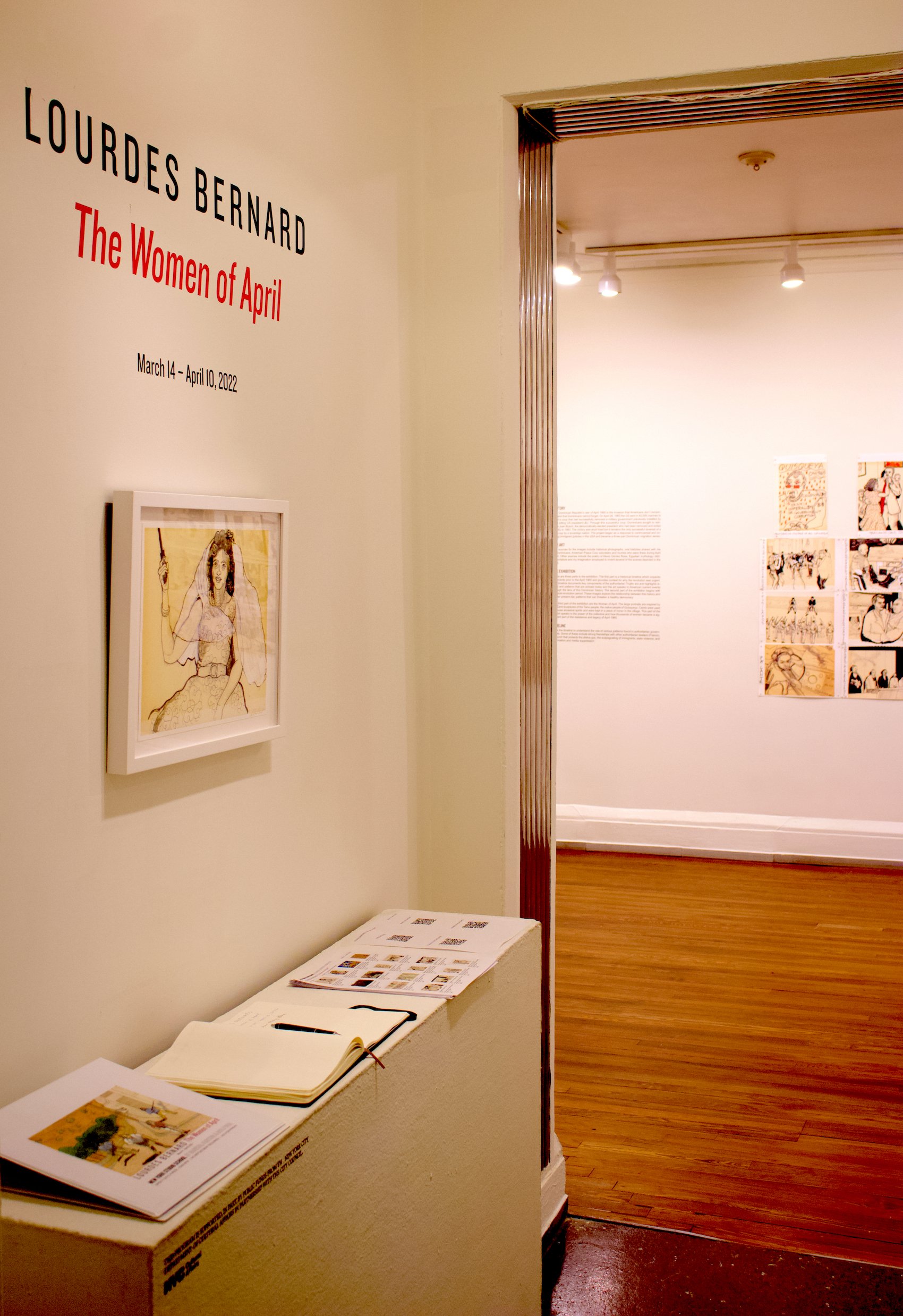

Lourdes Bernard is a Dominican-American artist who makes multimedia works on paper addressing historical events and how they take shape within a landscape. Her research-based practice unravels complex histories through visual storytelling, ultimately inviting viewers to contemplate shared experiences. Her most recent solo exhibition, Mujeres de Abril, is currently on view through Sunday, April 10 at the New York Studio School.

TLP: Tell us a bit about your newest body of work, The Women of April (Las mujeres de abril), and how these paintings fit into your broader research practice.

LB: "The Women of April" is a research-based group of works on paper that commemorate the upcoming 57th anniversary of the April 1965 revolution and U.S. invasion of the Dominican Republic. The narrative images celebrate and highlight the role of “The Women of April,” untrained civilian resistance fighters who fought against the 42,000 U.S. Marines ordered by Lyndon B. Johnson to invade the small Caribbean nation. Shortly after I attended the D.C. Women's March in 2017, the new administration began to roll out controversial immigration policies targeting vulnerable immigrant groups. I became curious about my own parents' migration journey and began historical research which led to a three-part Dominican Migration series. I wanted to unpack the catalysts that led to the creation of the vast Dominican diaspora, now the largest immigrant group in New York City. When I discovered the Women of April I knew I wanted to make images about them. The women were attorneys, journalists, artists, teachers, academics, housewives, and students ranging in age and economic status. I was particularly excited because I'd previously made images about women warriors as part of another body of work, "The Art of War," which I began several years ago when the war in Iraq entered its 9th year. Those images were colorful and figurative images exploring aggression in war as face to face encounters. In that work, the images I made were not tied to a particular history, people or conflict. In doing research for that series I came across the Dahomey warrior women, a.k.a. "The Minon," which means "our mothers," who faced off against the French when they attempted to colonize Benin. I made large format images of Warrior Women to deconstruct the notions of male power in a society informed by colonization. Some are rather large and monumental. When I discovered Las Mujeres de Abril it was familiar artistic territory and this time I got to make work where I had a particular connection to the historical context, so it was exciting.

TLP: Would you consider your work to be archival, or filling in historical gaps in popular memory that intentionally hide legacies of U.S. imperialism?

LB: Absolutely. The process of making images was very organic. I began researching the Trujillo era to better understand authoritarianism and also to reclaim the history which had led to April 1965. So the first set of 40 images begins with the Trujillo era and end with the April 1965 U.S. invasion, showcasing the Dominican civilian resistance and The Women of April. The works also unpack the immigrant narrative that is tied to U.S. militarism. This universal story is current and still unfolding today as we see people displaced by war rightfully fleeing for safety. The ink images are a prologue to April 1965 and yet they also mirror and name contemporary patterns that are found within all authoritarian regimes. For example, the works "Anatomy of a Dictator", "Water" and the three "Stop, Frisk" are all images which point to issues that we are grappling with today.

TLP: How does your own personal family history tie into your research on the U.S. invasion of the Dominican Republic in April 1965?

LB: Ciudad Nueva was a key Constitucionalista stronghold in the colonial part of Santo Domingo where the initial invasion of the Americas by Columbus also occurred 500 years prior. When the U.S. invaded Santo Domingo, my parents and siblings lived in Ciudad Nueva, in a house with a sunny courtyard and a parrot named Cuca. Our family was separated shortly after the invasion. Until I began this research I didn't know my story well enough to feel the impact of my immigrant experience. I made the first images in shock, then anger which gradually gave way to awe and that felt like a new beginning. It didn't settle anything for me that our time in Ciudad Nueva coincided with the U.S. bombing and occupation of Santo Domingo so I set out to document history as a way to witness what happened. I made drawings to fixate on something, to capture and digest the past clearly for the first time. The historical drawings became part of my story, which is also a universal story of immigrants forced to flee the instability created by war. This body of work raises questions about the impact of militarism and the cultural price of displacement and migration.

TLP: Does this history inform your approach to making drawings or paintings?

LB: The first set of images are a visual archive of the Trujillo era and the images are drawn directly in an old family album with yellowed pages. Using a restricted palette of sumi ink and gray washes allowed me to emphasize the shadows of this difficult history and to reinforce the sharp contrast between light and dark as a metaphor for authoritarianism.

TLP: How do audiences usually respond to your work? Does context matter? Does it depend on the audience’s relationship to the DR, or its diaspora?

LB: Well the audience responds to the work on two levels—first they respond to the art and then to the content. Proximity to this Dominican history doesn’t affect the response which is overwhelmingly strong and positive and moving. Once folks get past the shock that this history was unknown to them, or kept from them, they have expressed many feelings, including gratitude to a desire to learn more or feeling enlightened about this part of U.S. history and being “blown away” by the art. Most women connect to the empowering feminist images of Las Mujeres de Abril, and many men also find them inspiring. As part of the research I hand out a “beyond the exhibition” questionnaire to gauge the social impact of this work. Some of the American comments have been “I was surprised about the history of U.S. imperialism that I was ignorant about. I’m reminded how art adds another dimension to our experience and creates a more emotional and spiritual connection.” Other immigrants with similar diasporic histories have expressed a moment of encounter and recognition: “the same thing happened in my country South Korea.” Of course the most concrete responses come from Dominicans who express being touched by work that commemorates women who were central to the struggle in April 1965, a really important chapter in Dominican history. Many Dominicans shared their oral histories of April 1965 as they viewed the art and that makes it even more poignant.

TLP: Some striking works from The Women of April include women in poses of rest, while they simultaneously wield weapons. Specifically, Love as Resistance and Disobedience feature women in moments of respite (or even celebration) who still maintain their right to self-defense against an invasive militaristic empire. Are these poses informed by archival research or are they emotional portraits of brave women during a state of duress?

LB: The woman in repose with a gun in “Disobedience” is in fact a historical Mujer de Abril, Carmen Josefina Lora Iglesias. Nicknamed “Picky Lora,” she was a lifelong revolutionary and an attorney who played a significant role in April 1965. She was also the only woman who participated in the June 14th movement in DR, which attempted to overthrow Trujillo in 1959 by launching an invasion. So as a lifelong revolutionary it was fitting that even in rest she was prepared. The woman in “Love as Resistance” is fictional. The phrase comes from a conversation with a friend about how resistance is also about sustaining healthy connections to community, family, friends, and partners.

TLP: How do you use (or withhold) color in your works as a formal strategy for the creation of a mood or tone?

LB: As an oil painter I consider myself a colorist. However, in this body of work I reserved color primarily to depict The Women of April and sometimes to depict contemporary issues. When I looked at the historical photographs of these women I was struck by the many symbols of femininity , lipstick, curlers, manicured nails, and chanclas, and the juxtaposition of these symbols with the weapons they carried. The women simply showed up as themselves. There was something hopeful and life-giving about their determined participation in April 1965.

I wanted to celebrate that energy through the use of color.

TLP: How do you see your research evolving in the future?

LB: The process for this project was quite different for me. Before I began making the work I engaged members of various communities by asking them to share their stories with me of April 1965. This includes both Dominicans and Americans who were in the Dominican Republic during April 1965. Sometimes the images in this body of work were inspired by a phrase or just a part of a personal narrative. These personal accounts now live in the work which is now part of the legacy of April 1965. Using oral histories was new for me and very powerful and hopefully I’ll get to repeat that process for another project.

—

“Women of April” is sponsored, in part, by the Greater New York Arts Development Fund of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, administered by Brooklyn Arts Council (BAC). Presented by The New York Studio School, the exhibition is on view March 14 – April 10, 2022.

Lourdes Bernard is a Dominican-American artist raised in Brooklyn, a graduate of Syracuse University School of Architecture and The New York Studio School. Her work has been exhibited in El Museo del Barrio, the New York Public Library, PS1 Contemporary Art Center, Boston College, The Wilmer Jennings Gallery, and Five Myles Gallery. She is also the recipient of a Yaddo Foundation Fellowship and a Wurlitzer Foundation Fellowship.

Alex Santana is a writer and curator with an interest in conceptual art, political intervention, and public participation. Currently based in New York, she has held research positions at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Newcomb Art Museum, and Mana Contemporary. Her interviews and essays have been published by CUE Art Foundation, The Brooklyn Rail, Precog Magazine, Artsy, and The Latinx Project.