The Evolution of Queer Latinx Nightlife in Los Angeles

Far from the bars and clubs in West Hollywood, a neighborhood long known as the center of gay nightlife in Los Angeles, queer Latinos have long carved out spaces in their own neighborhoods that shifted the center of queer nightlife closer to home. From Club Tempo in East Hollywood that brands itself as the original gay cowboy nightclub with its frequent vaquero nights to Chico in Montebello that has always attracted a more working-class gay Latino clientele.

Even residential backyards in East L.A. became sites of placemaking for Latinos during the party crew scene in the 90s and more recently for the Maricón Collective who threw parties that were reminiscent of family gatherings and high school kickbacks but from a queer perspective.

Although many clubs that once defined queer Latinx nightlife in the city for decades have since closed their doors like Circus Disco and Arena nightclub, well known in the 90s for mixing deep house tracks until the early hours by iconic queer Latina DJ Irene Gutierrez, with her popular trademark call: “How many motherfucking Latinos are in this motherfucking house?,” queer Latinx parties continue to offer an important alternative space for those who feel excluded from the more mainstream gay venues.

Queer Latinx nightlife in L.A. has evolved over the years through a process of spatial entitlement, which scholar Gaye Theresa Johnson describes as the way in which “marginalized communities have created new collectivities based not just upon exclusion from physical places” but also the imaginative and creative use of these spaces to “articulate new modes of social citizenship.”¹

“Excluded from these collective identities,” Johnson writes, “aggrieved people have fashioned alternative expressions of collectivity and belonging.” This, in turn, provides a means for understanding how working-class queer Latinx communities and individuals create social membership into what scholar Jose Esteban Muñoz calls the brown commons, which is made up of “feelings, sounds, buildings, neighborhoods, and environments” in a brownness that is defined by “being with” and “being alongside.”²

“They are brown in part because they are devalued by the world outside their commons,” writes Muñoz, “but they are also brown insofar as they smolder with life and persistence.” Spatial entitlement and a brown commons offer a deeper understanding of queer Latinx spaces not only as important sites of placemaking but also demonstrates how clubs, bars and underground spaces formed counternarratives for the creation of new identities and identifications.

The Party Crews of the ‘90s

In the early 1990s, a generation of disaffected working-class Latino youth came of age in an environment marked by the 1992 L.A. riots, a period of heightened police surveillance against minoritized communities. Many Latino teenagers found solace by forming party crews in Los Angeles and its surrounding communities like El Monte, Montebello, Downey, and Hacienda Heights. These party crews would dominate the Latino underground landscape throughout the 90s, and it was in these spaces that many queer Latinx youth developed a sense of spatial entitlement that would shape queer nightlife in later years.

Carlos Morales, a Los Angeles DJ known as DJ Crasslos, grew up in Hacienda Heights and was first introduced to the party crew scene in his early teens by his older sister who was a member of a party crew. As Guadalupe Rosales, founder of the digital archive Veteranas and Rucas, writes in her photo essay When Chicana Party Crews Ruled Los Angeles, party crews allowed young men and women to engage in resistant cultural practices at a time when Latino communities in Los Angeles were often disempowered and criminalized.

For Morales, watching his older sister organize with a party crew inspired him to become part of one himself. He vividly recalls the diverse range of music that permeated the space, from house, techno, and drum and bass to freestyle and jungle music. As an openly gay Latino, Morales said that music was an element of the scene that united everyone, recalling how the lyrics of house music spoke about love, unity, and respect for one another.

“When you get into the beats in house music and let your body go, you just let yourself go, and you naturally break down that barrier you have of being very masculine” Morales said. “It was still very homophobic back then, and if you acted a little feminine, they would think you were gay. But at the same time, these homies were plucking their eyebrows and vogueing. It was a very queer scene. Some of these guys found these spaces as a way to express these repressed feelings. People weren’t afraid to be who they were.”

The party crew scene adopted a lot of the fashion and dance from rave culture and was heavily influenced by queer Black culture from the New York City ballroom scene, which highlights the way in which queer culture traversed through geographical boundaries to form a shared queer identity. Morales also describes how British new wave and glam rock artists, like David Bowie and Dead or Alive, promoted a more androgynous look that transgressed normative forms of gender expression, which also influenced the way in which gender was performed and reimagined within the party crew scene.

As the main core of that generation grew older, party crews eventually disappeared in the late 90s as club culture became more popular in Los Angeles. Many of the queer Latinx youth of the party crew generation became DJs and promoters for larger bars and clubs in the city, incorporating a lot of the music and cultural atmosphere into these spaces.

The Maricón Collective

Frustrated with the lack of queer brown spaces, Rudy “Bleu” Garcia started throwing parties in his late teens as a DJ in venues throughout the city, mixing everything from punk and 80s freestyle music to songs by the Mexican rock group Café Tacuba. By the mid 2000s, he became a regular DJ at the iconic Mustache Mondays, considered by many as one of the best queer parties in L.A. at the time. Started by the late Ignacio “Nacho” Nava Jr., Mustache Mondays redefined queer nightlife in the city by combining music and art with exhibitions and performances from Latinx artists like rafa esparza, Gabriela Ruiz, and San Cha.

The collaborative atmosphere that defined Moustache Mondays was a site of brown commons as queer Latinx people demonstrated their ability to strive and flourish in a shared space that embodied the nuances of everyday queer life, from the sights and sounds on the dancefloor to the visual representation of the fashion and performances that marked a shared queer Latinx identity.

After the success of Mustache Mondays, Bleu partnered with Carlos Morales and other queer Latino DJs to form the Maricón Collective. Created from a desire to “brown up the space,” the group played a mixture of cumbias, oldies, and house music in intimate locales like East LA residential backyards that were reminiscent of the party crew scene of the 90s. The events became increasingly popular because they offered a unique experience, which included go-go men in jockstraps pushing paletero carts while handing out popsicles in the shape of Juan Gabriel and Selena.

“We were consistently influenced by generations before us,” Bleu said. “We were just trying to have fun and listen to the music that we would listen to with our friends and family growing up but be in a space with our queer friends and partners while slow dancing to oldies or Los Bukis and not really thinking about what was happening outside those doors.”

“People really needed that,” Blue said. “They needed that home, they needed to feel seen, validated, and they saw themselves in us and we saw ourselves in them.”

Bleu and Morales would continue to DJ throughout the city after the Maricón Collective, with Bleu organizing the legendary Club Scum in Chico, a monthly queer Latinx punk party that mixed goth drag queen performances with the sound of iconic LA punk bands like the Germs, and Morales hosting a weekly radio program on the Boyle Heights community radio station KQBH.

The Plush Pony

Although many queer nightlife spaces have welcomed every spectrum of the queer community, Lesbian bars in L.A. have long provided a much-needed space for Chicana lesbians outside the more male dominated queer venues, with the iconic but since closed Plush Pony bar inspiring the late Chicana lesbian artist Laura Aguilar’s photo series of the same name.

“It was one of those spaces that if you blinked, you’d miss it,” said writer and educator Raquel Gutiérrez who has written extensively on queer nightlife in Los Angeles. “It was like entering a portal that felt like a large, converted garage, a very low budget sort of operation.”

The images that formed part of Aguilar’s Plush Pony series beautifully capture the diversity of that space as a site of brown commons, which offers a snapshot into the intimate bonds that were formed by Chicana lesbians in the early 90s. Described as a “butch/femme joint,” Gutiérrez writes how it was a space where Aguilar found a “sense of kin with its barflies.”³ Departing from her previous work photographing artists, academics, and activists in her Latina Lesbians series, Aguilar chose instead to focus her attention on the more working-class Chicana lesbian clientele that frequented the Plush Pony.

Located in the El Sereno neighborhood, the bar was one of the few nightlife venues in the city catering to Chicana lesbians. As Gutierrez writes, the Plush Pony signaled what it meant to be brown and queer from East Los Angeles in a time and space where “one could traffic in the promiscuity between the aspirational lesbian and the rough queer.” Unlike the subjects featured in the Latina Lesbian series, Gutierrez said the Plush Pony series captured the roughness of barrio nightlife in the faces of its anonymous subjects.

The black and white portraits offered a glimpse into the way in which Chicana lesbians engaged in spatial entitlement by converting the Plush Pony into a site of brown commons, one where the rugged queer could find commonality and kinship outside the nuclear family to form queer social networks in their own neighborhoods.

In The Brown Commons

For others like Joaquín Gutierrez, a longtime public health worker and founder of the monthly queer party Noches de Aay Tú, these spaces offered an opportunity to promote public health services to a community that has long been underserved and neglected. Gutierrez combined his experience as a DJ and public health worker to provide mobile rapid HIV testing centers outside Latinx bars and clubs, with Mustache Mondays being one of the first queer Latinx venues where Joaquín set up his mobile unit.

“Traditionally, a lot of these mobile testing units and services were being promoted in gay bars in West Hollywood,” Joaquín said, “but nobody was trying to reach out to the more underground queer spaces. I saw this as an opportunity to tap a part of the community that nobody was really paying attention to, and I knew how beneficial these resources could be.”

A native of Huntington Park in southeast Los Angeles, Joaquín started throwing queer Latinx parties at art shows and swap meets, which always included drag performances and rapid HIV testing on site. “We have to meet community where they are at,” Gutierrez said, “and we have to understand that when we are with community, we thrive.”

Bleu, Gutierrez, and Morales, all acknowledged that their parties weren’t the only queer Latinx parties happening in the city, with Gutierrez saying that his party was “just a piece of the story.”

Queer Latinx nightlife in LA continues to evolve as the queer Latinx community evolves. From Club Scum that provided a space for the queer punks to Chico that was always known as the spot for the queer homeboys and countless other spaces that were created out of a desire to collectively build a place where queer Latinx people would feel welcome.

“The reason these spaces are so important is because we’re getting to tell our stories the way it comes out of us naturally,” Gutierrez said. “The way we can take up that space and make it our own, being intentional with everything we do to center the black and brown experience. It’s important to tell our story through music, art, drag, fashion, but also through health and the importance of community by taking care of each other.”

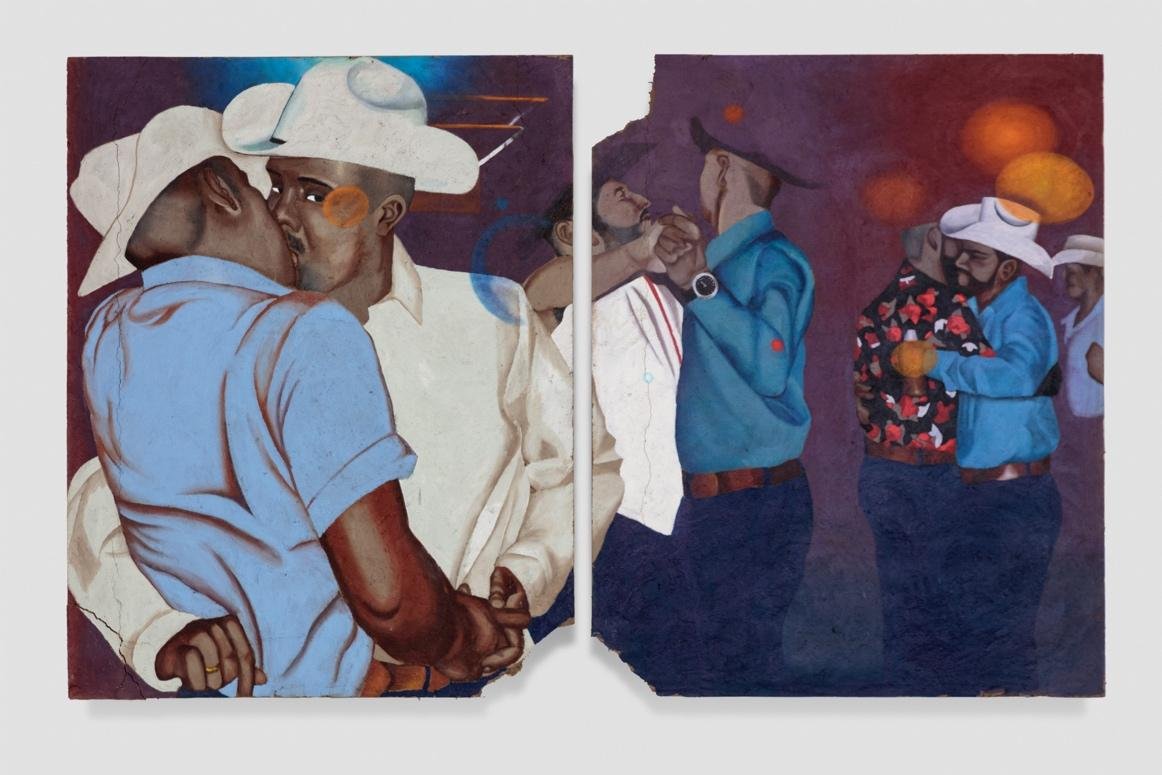

For me, queer Latinx nightlife in Los Angeles was always a space where I felt connected to a larger community. Being with and being alongside other queer brown folk made me feel like I wasn’t alone, whether it was dancing until the early hours to a familiar house beat by DJ Crasslos or ending my night at Club Tempo and watching two burly Latino men with their vaquero hats slow dancing together to a classic Mexican ballad. As Bleu said: “In the end, we didn’t want the night to end.”

Footnotes

¹ Spaces of Conflict, Sounds of Solidarity: Music, Race, and Spatial Entitlement in Los Angeles, 2013, UC Press, Gaye Theresa Johnson.

² Muñoz, José Esteban, The Sense of Brown. Duke University Press.

³ A Vessel Among Vessels: For Laura Aguilar, Memories of a dyke bar in East LA conjure and are conjured by the work of Laura Aguilar, Raquel Gutiérrez, THE NEW INQUIRY, 2018

Jorge Cruz is a PhD student in Chicano/a Studies at UCLA and received his master’s degree in Latin American Studies from Cal State LA. His research explores queer representations in Latinx art. He was also a summer intern at the Latinx Project.