The Colonial Roots of White Supremacy: Lessons from Latinx History

We have entered a new era of white supremacy in the United States. From the separation of families at the US-Mexico border to the criminalization of refugees and the rise of hate crimes, we in the Latinx community may feel overwhelmed and uncertain about our political future. Yet today’s anti-immigrant, anti-Latinx rhetoric, is not a recent development. Rather, it has some of its earliest roots in the dispossession of Mexican Americans in the 1840s under Manifest Destiny and in their lynching in the 1920s under Jim Crow, among other racist policies and practices. It is therefore essential for us to recall this history of repression under white supremacy and resistance to it.

Modern society is founded upon the racist belief that the white race is inherently superior to all others. White supremacy originates in the fear that white privilege will end because of a newly-risen, presumably non-white collective. For centuries, white supremacy in the Americas has used two main tools to protect white privilege. First, it has relied on phenotypically white people, the historic recipients of white privilege, to align with this ideology. Second, it has created fractures within communities of color through light-skin privilege and internalized racism. The Latinx community, as a multi-racial cohort, has been subjected to both means of control by white supremacy.

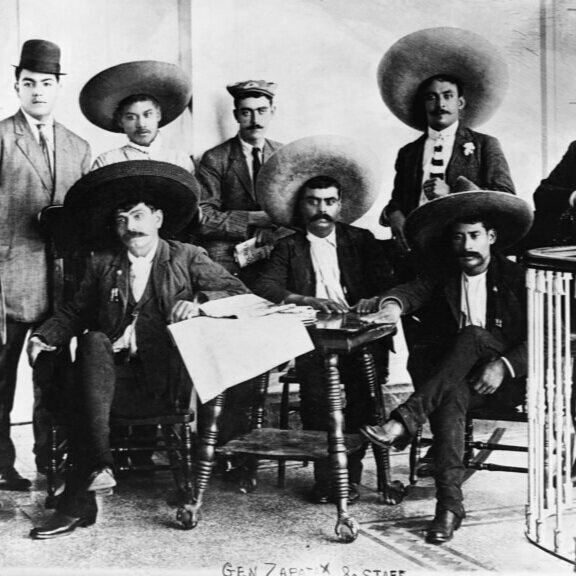

Let us take the case of colonial Mexico as an example. When the Spanish first arrived at present-day Mexico, they implemented the “casta” system. With it, they placed themselves at the top of a racially-informed hierarchy and distinguished themselves from presumably lesser “others,” especially those of mixed-race identities. This system was formally challenged by the Mexican fight for independence in 1810, which united “criollos/as” (those of “pure” Spanish-descent born in present-day Mexico) with “mestizos/as” (of Spanish and indigenous origin) and the territory’s indigenous and black populations. After renewing its commitment to an inclusive citizenship through various iterations of the Mexican Constitution, the country became similarly united across racial and ethnic lines under the Mexican Revolution of 1910. In this case, it did so by establishing a shared, working class identity against dictator, Porfirio Díaz, friendly to elite US and European capitalist investors.

Conversely, after the Mexican-American War of 1846, in which Mexico lost more than a third of its territory to the US, elite Mexican Americans distanced themselves from their indigenous roots. This they did to gain favor as new citizens in the US under the black–white binary, which stipulated that to be white was to be free and to be black was to be enslaved. Of course, this process of “blanqueamiento” (whitening) did nothing to protect darker-skinned Mexican Americans. Indeed, those unable to “pass” for white were subject to extreme forms of racialized violence, from losing their claim to collectively-owned land under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, to experiencing segregation alongside African Americans under the Jim Crow laws.

In the 1960s, Chicanos/as (politicized Mexican Americans) interjected into the US’ black–white binary through the language of mestizaje (the mixing of races in Mexico, especially between Spanish and indigenous peoples). To identify as a Chicano/a was to take pride in one’s mestizo/a heritage and to demand cultural, political, and intellectual space within US society at large. In the 1980s, Chicana feminists spoke against the Chicano movement’s sexist and homophobic tendencies. Under the guise of “US women of color feminism,” they also joined their Black, Native American, Asian, and/or LGBTQ activist peers in modelling the era’s belief in unity in difference. As these separate, but overlapping, histories teach us, Mexican and Mexican-American becoming of the modern liberal era is tied to moments that have directly opposed white supremacists’ “divide and conquer” political strategy.

I believe today’s broken immigration system has led to the creation of an equally divisive “us” versus “them” dichotomy in the US. This time, white supremacist fears have taken the form of a white citizenry under attack by so-called illegals, almost always racialized as non-white. To combat this, we, as a racially diverse Latinx people, must not turn away from ourselves and each other and adamantly reject the US’ current project of nation-building under white nativism. At times, this will take the form of a return, for example, to a 1960s insistence that Latinx history is US history or to a 1980s vision for coalitional politics. At others, it will take the form of new political alternatives altogether. Regardless, we must not be fooled into believing that compliance with a system of racial inequality will ever lead to our protection and invest instead in new forms of political belonging for our communities of color and white allies. After all, for every time we have faced political precarity under a white supremacist state, we have also become anew as a collective by radically resisting it.

Nicole Eitzen Delgado–from Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico–was the Latinx Project’s graduate research working group coordinator from 2018 to 2019. In 2020, she earned her Ph.D. in English and American Literature from New York University and in 2015, her M.A. in Comparative Literature from Dartmouth College. As of the 2020-2021 academic year, Eitzen Delgado is a postdoctoral fellow in the program of Latino/a Studies in the Global South at Duke University. Her current book project examines the captivity narratives, broadly conceived, of two borderland captivities of the Latinx nineteenth century in the United States and Mexico.