Star Wars and the Ongoing Problem of Race

Just days before the latest Star Wars series, Obi-Wan Kenobi, premiered on Disney+, actress Moses Ingram began to receive an outpour of racist comments on social media from fans who were opposed to her casting as the main villain of the series. This, in turn, prompted Ewan McGregor, who played the title role and was also an executive producer of the series, to release a video indicating his support for Ingram, and on May 31, 2022 the official Star Wars Twitter account tweeted, “We are proud to welcome Moses Ingram to the Star Wars family and excited for Reva’s story to unfold. If anyone intends to make her feel in any way unwelcome, we have only one thing to say: we resist.”

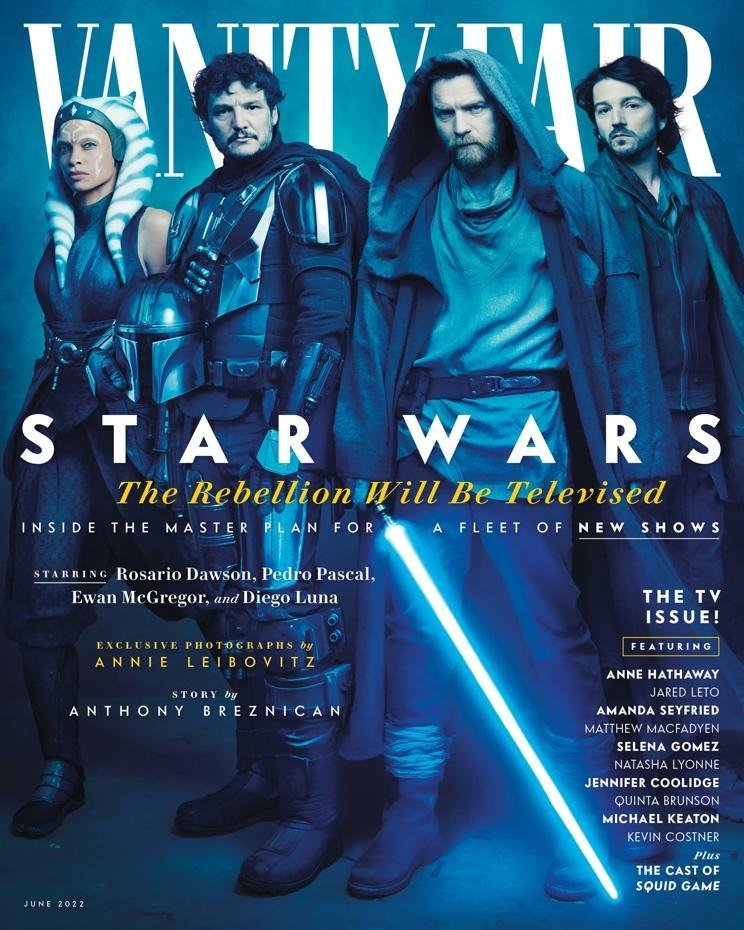

The Obi-Wan Kenobi series stands out for featuring one of the most diverse Star Wars casts, including characters played by Jimmy Smits, Sung Kang, Indira Varma, Kumail Nanjiani, and O’Shea Jackson Jr. Disney executives have been more proactive about including non-white people in their narratives over the last decade. They have also dedicated quite a bit of attention to showcasing this diversity through press materials. Just days after Disney publicly decried the racist tweets, Vanity Fair ran an article titled, The Rebellion Will Be Televised, which featured Latinx and Latin American actors Rosario Dawson, Pedro Pascal, and Diego Luna (Figure 1).

There is a clear tension, however, between Disney’s rhetoric of inclusivity and the moments of racist outcry from fans who feel deeply invested in the franchise. Today, Disney executives are caught in a perpetual cycle of casting actors of color in lead roles and then publicly defending them from a small, but vocal public. This is only the latest iteration of the franchise’s race problems. Since its initial release in 1977, Star Wars has demonstrated the possibilities for the inclusion of alternative identities within science fiction, but has also underscored how those possibilities are limited when they confront the racial politics of the real world.

In his critique of the first two Star Wars trilogies, Wetmore argues that Lucas’ films have always reflected an ambivalent racial politics. Written during the final days of the Vietnam War, the original Star Wars films were meant to be a critique of colonization. In their execution, however, they reinforced racial hierarchies. The Empire was depicted as all human, all white, and primarily British, and there was also a notable absence of people of color. Non-white characters were literally represented as the alien other. Fantastical creatures based on real life stereotypes: the savage Indian, the treacherous Asian, the Black minstrel, and so forth.

In 2012, The Walt Disney Company acquired the Star Wars franchise from George Lucas for 4.1 billion dollars, which resulted in a notable shift in its casting strategy. Driven by global ambitions, Disney needed to appeal to more diverse audiences worldwide. As Sean Bailey, Disney president of motion-picture production, asserted “inclusivity is not only a priority but an imperative for us, and it’s top of mind on every single project.” Bob Iger, former chairman and CEO of the Walt Disney Company, put it more directly: “Diversity is not only important; it is a core strategy for the company.”

When Disney began producing their own Star Wars films, the company attempted to directly address the gender and racial inequities that were inherent in Lucas’ original films. British actresses Daisy Ridley and Felicity Jones were cast in lead roles, while actors of color were cast as supporting characters, including John Boyega and Kellie Marie Tran, who was also attacked extensively on social media. Even Latinx actors, which had previously been ignored, found a place in the new Star Wars universe. Diego Luna, Oscar Isaac, and Benicio Del Toro all had feature roles. Still, Disney’s attempts to address the gender and racial inequities of the Lucas films appeared superficial at best. John Boyega, who played Finn in the sequel trilogy, spoke out about Tran’s online racial abuse as well as the Walt Disney Company’s tokenistic use of non-white characters through an interview with Vanity Fair. In the interview, Boyega blames the company for sidelining him and other non-white characters in the films themselves but promoting the diversity of the galaxy via advertisements and promotional materials.

With the launch of the streaming platform Disney+ in 2019, Disney shifted its distribution strategy, which increased the opportunities for Latinx, Black and Asian actors. Star Wars was seen as an asset that could entice new subscribers, and so Disney temporarily suspended the cinematic release of Star Wars films, instead focusing on episodic storytelling, which is more conducive to streaming platforms. The strategy appears to have been a success. The Mandalorian was the first original series to run exclusively on Disney+, and has largely been credited for the platform’s successful launch.

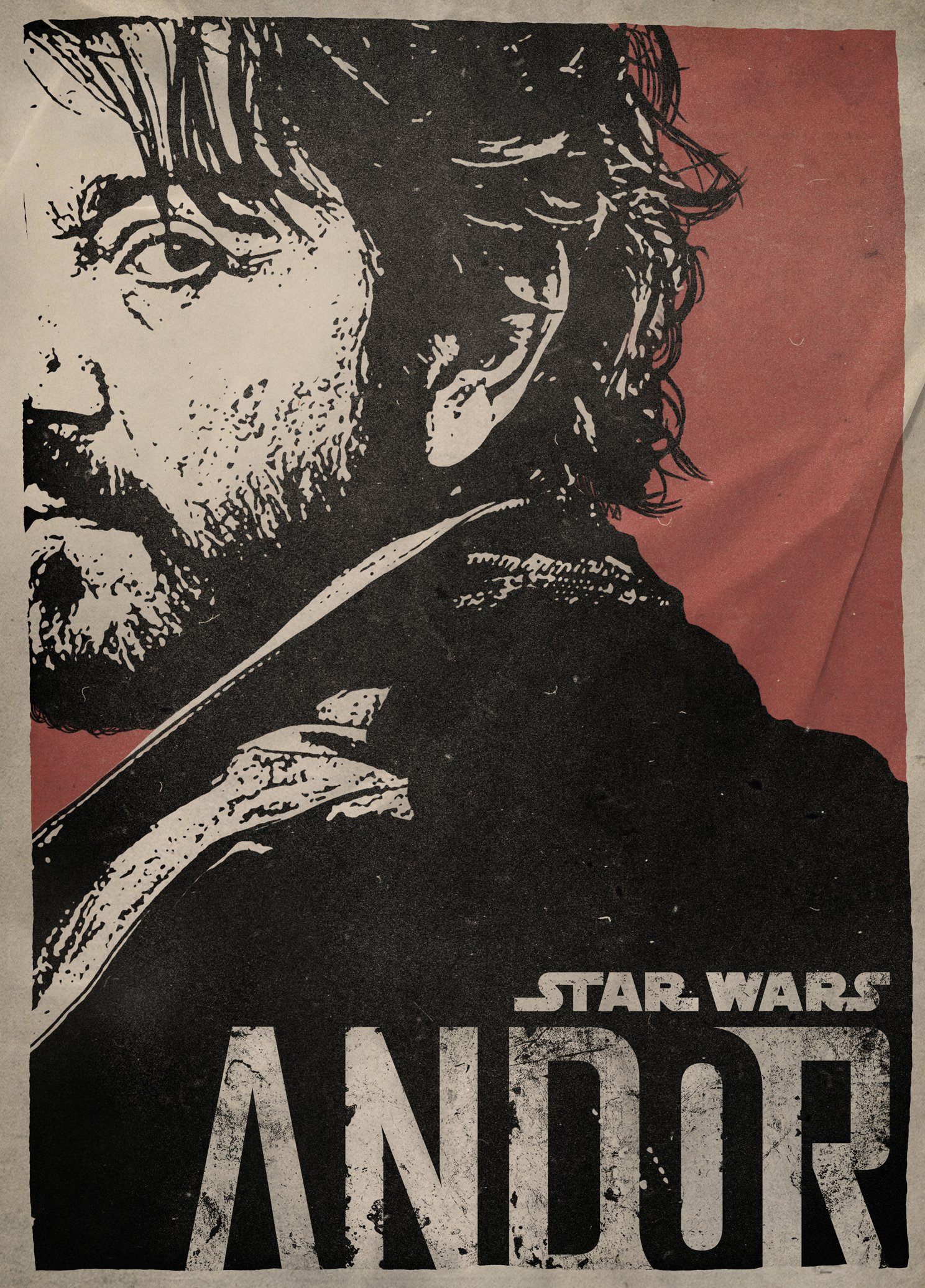

But the larger plan was always to integrate Star Wars throughout Disney’s key units, including its video games, merchandise, and theme parks. This kind of extensive world-building requires more characters. Lots of them. Suddenly people of color were everywhere in the Star Wars universe. Latinx actors were playing both colonizer and colonized. Chilean actor Pedro Pascal was The Mandalorian himself, albeit speaking in an American accent and with his face obscured for most of the series. He was joined by Rosario Dawson, whose character Ahsoka Tano is rumored to have her own show in production. Their main foe was Moff Gideon, played by Giancarlo Esposito. In August 2022, Diego Luna will headline the series Andor, reprising his role in Rogue One.

As they have done with their other properties, Disney has taken a colorblind approach to casting, in which the characters are presumed to operate in a world in which racial difference simply does not exist. This is not to say that the Star Wars universe is not racialized. In our research, we found that many settings within the Star Wars universe are depicted as global borderlands, composed of signifiers of the global south as well as the American frontier. In this way, the Star Wars universe resembles other global borderlands that exist within science fiction literature, consisting of criminal, multi-ethnic settings that should be feared. This is consistent with Lucas’ original vision for the franchise, which took place not at the center of the galaxy, but at its margins.

In his book, Black and Brown Planets: The Politics of Race in Science Fiction, Lavender argues that science fiction is the ideal genre in which to critique present day issues. Focusing on Latinxs specifically, Merla-Watson’s and Olguín’s anthology Altermundos: Latin@ Speculative Literature, Film, and Popular Culture builds a case that the genre can be used to confront colonialism, immigration, and globalization, and in her own work, Catherine Ramírez advances the concept of Chicanofutursim, which explores the relationship between gender, race, technology, the environment, and the future from a distinctly Chicanx perspective.

At its best, science fiction has been used to envision viable political futures in which people of color play an important role in advancing human destiny. However, such lofty visions of the future are not disconnected from the unfortunate realities of the present. As noted through the work of Safiya Umoja Noble, everyday technologies have not been used to create new political possibilities for people of color, but rather to reinforce existing hierarchies. These technologies include search engines as well as social media. Social media platforms lend themselves to types of attacks we could not have witnessed during the release of the first Star Wars films. Fans may have been disgruntled in 1977, but they did not make themselves vocal via Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and the like. The last 5-10 years have seen an increase in racial animosity, leading to a predictable pattern of casting, followed by public trolling, followed by public defense.

Certainly, this is not unique to Star Wars. Fans of other science fiction-based films have been critical of filmmakers for allowing actors of color into presumed white spaces. But Star Wars occupies a unique space in popular imagination. Few other film franchises have inspired the same kind of passion from their fans, who feel deeply invested, and therefore, a sense of ownership over what is accepted Star Wars orthodoxy. Disney has been aware of the flaws in its fandom for a long time and has developed a script for dealing with these occurrences.

Sometimes the power of fandom works to uplift non-white communities (like when Latinx communities advocate for Latinx television series to remain on air), while other times it works to continue reinforcing systems of oppression and racism (like the attacks on Moses Ingram). This social media pattern puts Disney and Disney talent in a position where they have to publicly step in and take on the role of advocate/ally, although the comments from the company and the stars are typically tenuous at best. This, however, is not limited to Star Wars. In 2019, for example, when Disney announced that the new live-action The Little Mermaid would feature Halle Bailey as Ariel, the internet went wild with the #notmyariel hashtag, which included a slew of racist comments explaining how/why Ariel could not be Black. Through these virtual backlashes, we can clearly see how audiences speak out when they believe their vision for a white, fictive imaginary is not fulfilled. The characters, which audiences find problematic, are very much works of fiction, in planets and kingdoms often difficult to pronounce, yet they speak to larger racial anxieties beyond the screen.

Whether or not this kind of racial animus will extend to Andor, which will be released in August 2022, has yet to be seen. Reprising his role as Cassian Andor is Diego Luna, a Mexican actor performing in a Mexican accent. When his character first debuted in Rogue One in 2017, the Washington Post published an article on Luna’s decision to not change his accent, and the meaningful impact this had on Latinx and Latin American audiences. Joining him will be Puerto Rican actress Adria Arjona Torres. Disney may yet feel compelled to again step in and defend their actors, but to date, the casting of Latinxs and Latin Americans has not yet prompted the same backlash as the casting of their Black and Asian American counterparts. This could be because Latinidad is more flexible and malleable. The racial and ethnic ambiguity of some Latinx actors lends itself to less critique from audiences; the ambiguity proves less threatening.

Still, Disney suddenly finds itself in the role of ally, and their public efforts to address racism function as a form of corporate social responsibility. This kind of corporate posturing however, obscures Disney’s tepid approach to race within the Star Wars franchise itself. Unlike more political works of science fiction, which use the genre to interrogate critical racial, economic, and political issues of the present, Disney continues to turn a blind eye, instead depicting an alternate universe in which race is present, but simply not a factor…until it is.

Christopher Chávez is an Associate Professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at the University of Oregon and the Director of the Center for Latina/o and Latin American Studies. His research focuses on Latinx studies, cultural production, and globalization. Chris is author of The Sound of Exclusion: NPR and the Latinx Public and Reinventing the Latino Television Viewer: Language, Ideology, and Practice.

Diana Leon-Boys is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and affiliate faculty in the Department of Women's and Gender Studies and the Institute for the Study of Latin America and the Caribbean at the University of South Florida. Her research and teaching interests are in critical media and cultural studies, Latinx studies, and girlhood studies. For recent publications and other projects visit dleonboys.com