A Letter to Sandra Guzmán: Reflections on ‘Daughters of Latin America’

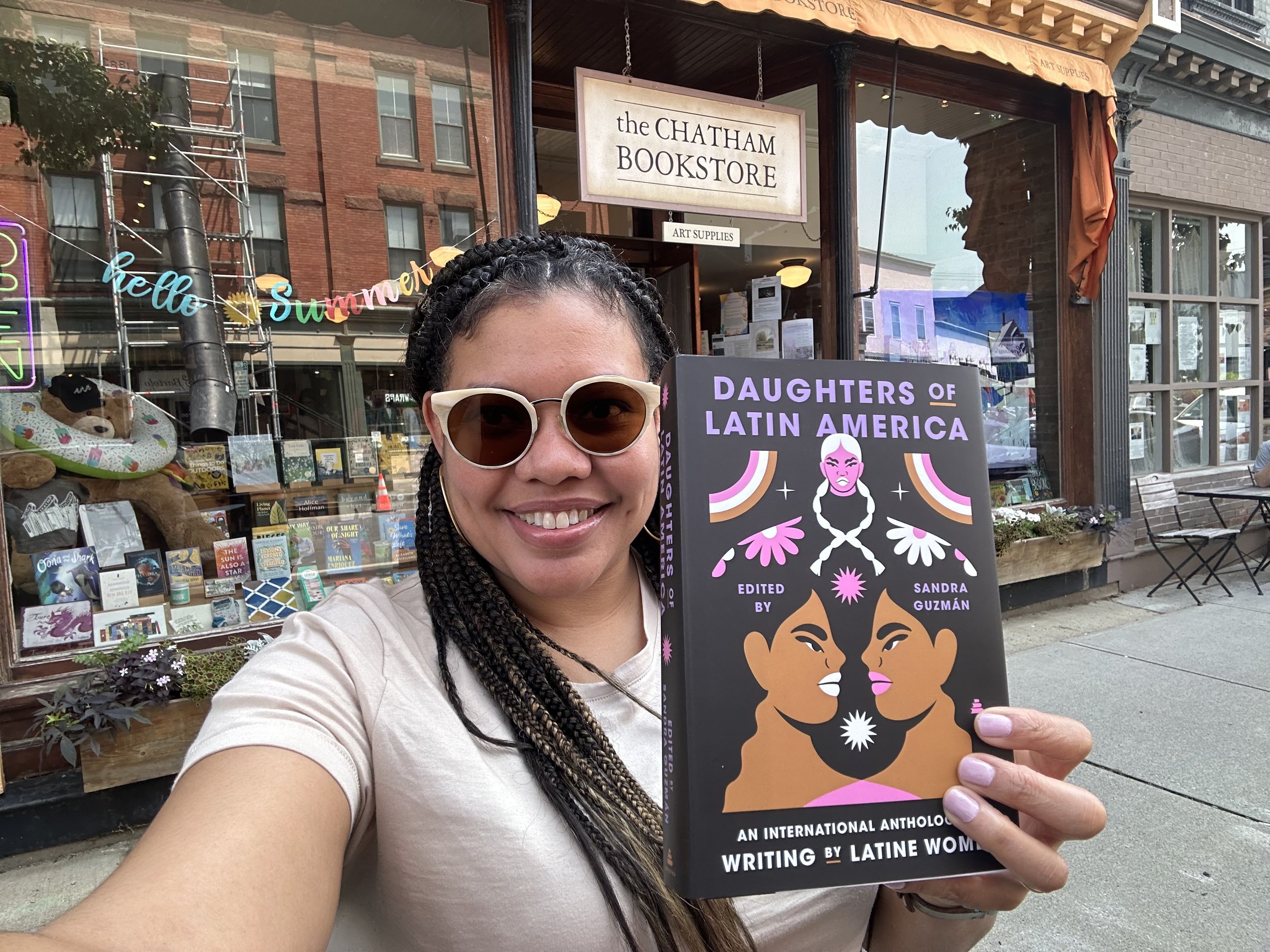

This essay is in the feminist tradition of letter writing present in This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, among other volumes. This sister-to-sister correspondence is my intellectual offering about Sandra Guzmán’s Daughters of Latin America: An International Anthology of Writing by Latine Women.

Hey girl!

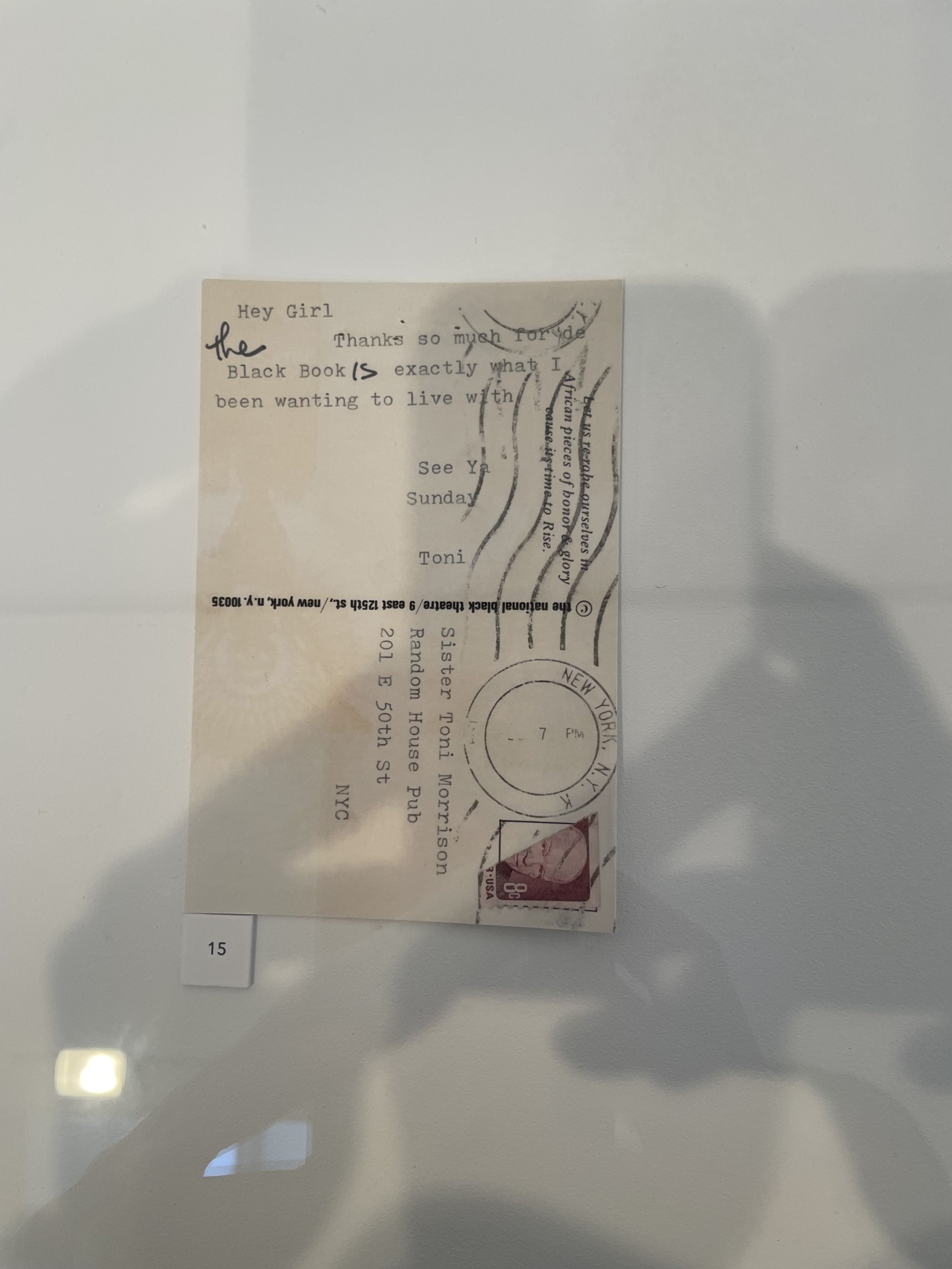

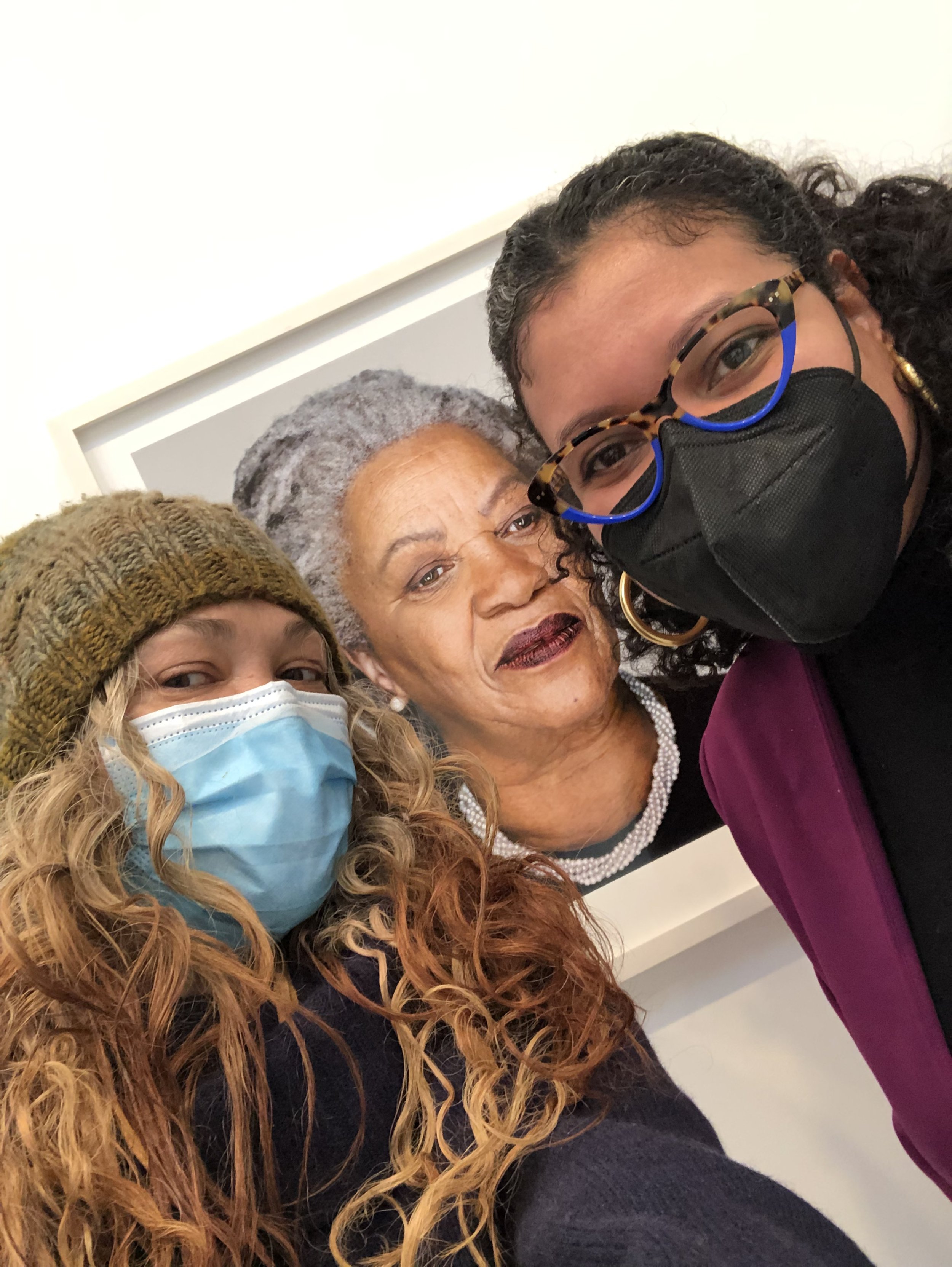

How are you doing? I hope Mother Moon is treating you well. I was thinking about the time we went to the exhibition about Toni Morrison in Chelsea. I’ll never forget finding the postcard from Toni Cade Bambara addressed to Morrison.

We both caught the sisterly salutation, “Hey girl.” That familiar phrase made us laugh like schoolgirls! Do you remember that? From then on, we texted or emailed each other with that greeting.

Morrison curated The Black Book to challenge master narratives of the history and culture of Black people in the U.S. In the same way, you curated a tome that catalogs the vast experiences and stories of daughters of Latin America to challenge conventional notions of Latine women, femmes, and nonbinary folks. Like Bambara, I’m writing to thank you for bringing forth an anthology that is “exactly what I been wanting to live with.”

As an interdisciplinary Black Latina feminist scholar born in the U.S. and sister friend, I share my review of the contributions that Latinx contributors made to Daughters of Latin America (DOLA). Of the 140 contributors, I estimate you can classify 43 as “Latinx,” having been born or raised within the United States. I selected 12 of the Latinx contributors for this review. Girl, let me tell you! It was so hard to select them because the brilliance is abundant in this collection. While I examined all 43 texts (and would have loved to analyze them all), I had to follow the emergent themes supporting my analysis.

Speaking of analysis, I found it fitting to draw on the methodological scholarship of a Brazilian woman of color researcher, Mariana Souto-Manning. She describes her approach to discursive meaning-making as “critical narrative analysis.” It examines the narratives broadly for instances of “institutional discourse” (power talk) and “lifeworld discourse” (everyday talk). Furthermore, Souto-Manning considers the grammatical agency at the sentence level to find the interactions between the institution and lifeworld. In other words, what can we learn about “macro level power inequities and micro level interactional positionings” when examining the sentence structure of the texts? My goal here—a close read of selected sentences and phrases—is to explore these narratives as examples of some of the challenges and opportunities of the Latinx experience.

“This idea of blessings and curses aligns well with the book’s ethos grounded in ceremony, ritual, and ancestral knowledge. ”

By reading Cherríe Moraga’s fragment, “How to Bless,'' I found the conceptual framework that would hold the themes of this analysis together. In this no-frills story about family and tradition, I kept coming back to the word “bless,” which she repeats three times. The exploration of the word “bless” led me to its derivative: blessing. This word unlocked the key to my thinking and enabled me to see the discursive undercurrents that I found in the dozen texts: blessings and curses. This idea of blessings and curses aligns well with the book’s ethos grounded in ceremony, ritual, and ancestral knowledge.

The introduction of the book, “A Literary Ceremony” and Moraga’s piece about blessings inspired me to frame my findings in the context of blessings and curses. Drawing from your idea of literary ceremony, I take the opportunity to examine the blessings and curses within the dozen texts. Each writer depicts Latinx identity and experiences differently through prose, poetry, playwriting, and speeches. I found curses of coloniality, poverty, and disgust. On the flip side, I simultaneously read about the blessings that resulted from these curses, which looked like the recuperation of identity and the formation of entremundoness. Therefore, I argue that Latinx DOLAs are wrestling with the blessings and curses of our lives, identities, and experiences in the U.S. context.

The Curses of Coloniality, Poverty, and Disgust

Let me start with the curses. When I use the term “curse,” I am referencing the institutional discourses of violence that appear in the texts and allow us to see the macro-level harms and oppressions the writers or protagonists experience. The texts contained a variety of curses, but I want to focus on three particular ones that reverberated across them: coloniality, poverty, and disgust.

The Curse of Coloniality

Drawing on Caridad de la Luz’s fragment from the play Anacaona Airlines, Nicole Cecilia Delgado’s poem “Translation,” and “El Charco,” the fragment from Yasmin Hernandez’s memoir, it comes as no surprise that these Boricua writers incisively narrate in their own way the curse of coloniality. De la Luz humorously and immediately invites us into the tension of Borikén’s colonial status with lines like, "Life vests are nowhere to be found because this is what colonization feels like'' and "be grateful for citizenship and that the lavoratorios are overstocked with paper towels and toilet tissue.”

While de la Luz gives us a feeling of coloniality through satire, Delgado’s poem reacts to it. They write about coloniality as anger-filled statements and questions like "America you’re your own worst enemy" and "When will you listen to our million dissents?" The last stanza in the poem, though, is a final, LOL-worthy middle finger to U.S. imperialism: "America I offer your History my big ass."

Turning to Hernandez’s memoir piece, “El Charco,” we look inward at her lifeworld rather than the institutional discourses of state-sanctioned harm against Boricuas in de la Luz’s and Delgado’s works. However, like Delgado, Hernandez narrates the reaction or impact of coloniality, which she calls “colonial trauma.” For her, the impact of the curse of coloniality shows up in “the risk of being denied our identities” and being from “neither here nor there.” Taken together, these texts render visible in humorous, angry, and honest ways the 126-year complex imperial relationship between Borikén and the U.S.—a blessing or curse depending on who you talk to, cierto o no?

The Curse of Poverty

We know from lived experience and our work—your journalism and my study of sociology—that poverty has disproportionately affected Latinx families and communities. Sis, and we also know that, in this country, this is a racialized and gendered structural issue. Three DOLA contributors set the stage for this curse of poverty in U.S. urban contexts: Naima Coster’s piece, “Reorientation,” Elisabet Velasquez’s poem, “20 Years Later Mami Apologizes,'' and Quiara Alegría Hudes’s short story, “Anyone Know a Down Barrio Architect?” Their collective pieces shed light on the intricacies of racialized and gendered socioeconomic class in New York City and Philadelphia.

“Poverty has disproportionately affected Latinx families and communities. . . In this country, this is a racialized and gendered structural issue. ”

Coster’s narrative about transitioning from dutiful public school pupil to elite private school “mean girl” is exceptionally sharp when recounting the dual life she begins to inhabit, and the power struggles she begins to experience with her family and ultimately herself. This text showcases both lifeworld and institutional discourses as Coster narrates her fixation with assimilating to the culture of New York City’s white economic elite class. She writes, “I watched them wrap their bodies around their chairs in class, one foot up on the seat, the other leg folded underneath them.” And, “At night I clipped a clothespin to my nose, hoping it might narrow.” Despite her anthropological study of her classmates and their wealth, Coster still experienced the curse of poverty with questions asked of her by peers like, “What are you?” and “Where are you from?” to jokes at the expense of Black people.

Like Coster, Velasquez’s perspective is that of a working-class Latinx New Yorker. The curse of poverty is palpable in Velasquez’s poem from the first three stanzas. We instantly learn she is a teen mother, working a 6 a.m. food service job. Velasquez does not have custody of her 1-year-old daughter. The economy of those words that open this poem conveys far better the experience of a working poor mother in George W. Bush’s America than any sociological study I’ve read! Velasquez does not stop there, and we most viscerally feel the curse of poverty when she writes, “I only had one quarter. I had a choice to make. Call you or my daughter.” These words make us feel the economic limits and familial complications that deepen our understanding of her lived experience. The poem’s setting on September 11, 2001—a day that marked the onset of future colonial trauma like the War on Terror and the Patriot Act—demonstrates how it contains both institutional and lifeworld discourses.

While Philadelphia is only a short train ride from New York, it can seem like a world apart. Nevertheless, Hudes finds a way in her fantastical short story to remind us of the universality of the curse of poverty. Set in a magical library that contains books and collections of Borikén’s diaspora, her short story is an homage to Puerto Ricanness with references to Vicks VapoRu, Orchard Beach, Fania 8-tracks, and Hudes's maternal side, the Perez family.

The curse of poverty appears in the description of the funeral card archive in which she finds several with causes of death listed as AIDS. The years of fatalities ranged from 1989–2007, with the majority in the 1990s, the height of the AIDS epidemic in the U.S. Research demonstrates a link between high HIV rates and poor urban areas—a curse of poverty. Hudes is no stranger to the AIDS epidemic and wrote openly about its effects on her family in her 2022 book, My Broken Language: A Memoir. The curse of poverty still looms large today, especially in this recession, because we know all too well that here in Ámerica, a nickel costs a dime.

The Curse of Disgust

In her book Politics of Disgust, political scientist Ange Marie Hancock asserts that misperceptions of public service recipients (e.g., “welfare queen”) resulted in “legislative outcomes that are undemocratic both procedurally and substantively.” In other words, Hancock points to the flawed nature of policymaking due to stereotypes and political dog whistles that she calls the “politics of disgust.”

Drawing on Hancock’s idea, the curse of disgust is at the forefront of two speeches given 47 years apart by two New York Latinx leaders: Sylvia Rivera, a transgender and gay liberation activist in 1973, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a U.S. House of Representatives member in 2020. In both speeches, they call attention to the disgusting treatment they’ve experienced as a result of their racialized and gendered identities.

In Ocasio-Cortez’s case, she exposes verbal assault from a male U.S. House of Representatives member “on the steps of our nation’s Capitol.” In Rivera’s case, she lodges a complaint against those Gay Pride parade attendees who “belong to a white middle class white club.” While both groups—elected officials and white middle-class people—typically hold more power in the U.S. context, Ocasio-Cortez and Rivera do not hold their tongues. They use direct language when speaking to these powerbrokers. Ocasio-Cortez used her platform as a sitting Congress member to lodge a formal and public complaint on the congressional record.

Similarly, Rivera used her platform as a transgender activist at the Pride parade to amplify the lives of incarcerated transgender and gay folks, as well as LGBT youth living in shelters. In these public spaces, they address powerbrokers head-on and demonstrate to onlookers and listeners that women—straight and queer—have the power to liberate themselves from harm and violence.

The Blessing of Recuperation and Entremundoness

While the curses of coloniality, poverty, and disgust foregrounded this essay, I’m delighted to close it by articulating the blessings that also result from them. Porque no hay mal que por bien no venga! Two kinds of blessings appear in the remaining texts: recuperation and entremundoness. In the selected texts, I see blessings related to recuperated language, land, or identity. Similarly, the blessing of in-betweenness, or what Gloria Anzaldúa calls “entremundo,” is another salient theme I could not unsee.

The Blessing of Recuperation

Recuperation has two definitions—the first relates to healing from illness, and the second refers to recovering something lost or stolen. How befitting, verdad! Coloniality, poverty, and the politics of disgust are curses born out of socio-political illness and theft. In these texts, recuperation of identity was a salve or healing agent for many to fix the social ills or curses; in this way, recuperation is a blessing. Two DOLA contributors help us to see this idea of recuperation of identity, place, home, and language: Sonia Guiñansaca’s poem, “Runa in Translation,'' and Yesika Salgado’s poem, “Land of Volcanoes.”

Guiñansaca’s poem is an ode to longing. Specifically, they long to speak in their people’s native Kichwa. They incisively capture their pain to recuperate language with these words: “The hurt is felt in three languages.” This powerful stanza demonstrates the curse, yet they signify their effort to recuperate language by their willingness to learn the language via Zoom during the pandemic. While an imperfect solution to heal their broken tongue, the blessing of recuperation is that they are recovering the language that was taken from them when they were "plucked from Ecuador and flown to the U.S.''

Guiñansaca’s poem of the Latinx selections is the only poem that speaks directly to the recuperation work of Indigenous people in the U.S. context. Like Guiñansaca, Salgado’s poem is about longing and desire for connection to identity. Instead of longing for language, it is about longing for homeplace. Drawing on images from the “country that birthed my parents”—mango trees, dirt roads, pupusa vendors, and tin roofs—El Salvador comes alive in Salgado’s verses. She wrestles with both feeling connected and being “a stranger at your door,” which signals a kind of distance, such as being served the “last bits of coffee” or given the “best chair” in the house.

While one can read this tension of distance as a curse of the Latinx identity, I believe Salgado ends the poem by recognizing the blessing of maintaining a connection to El Salvador by physically locating homeplace in her body, a “heartbeat” and a “bruise that I hope never heals.” And this is the work of recuperation.

The Blessing of Entremundoness

In Anzaldúa’s work, she writes about the in-between or interstitial spaces she refers to as nepantla or entremundos. Though implicit ideas of entremundoness appear in Guiñansaca’s and Salgado’s poetry, they most explicitly appear in the personal narratives by Norma Elia Cantú and Hernández.

A self-described “nepantlera,” Cantú brings us into the complexity of the Texas borderlands, also known as la frontera. I understand intimately when she talks about being “an in-between survivor.” This is where my mother’s people are from, and I see this entremundoness in my own family.

“Though the curse of coloniality fractures geographies, families, language, and culture, it also brings a blessing in creating a new identity through entremundoness”

Though the curse of coloniality fractures geographies, families, language, and culture, it also brings a blessing in creating a new identity through entremundoness in what Cantú calls “tejanidad.” This new way of talking, dancing, and being is specific to South Tejas; you can see it in Spanish words like “huerca” and “espauda”—words mi abuela and tías uttered. Like tejanidad, we learn about the charco-crosser entremundo identity in Hernández’s personal narrative. While the border between the U.S. and Mexico is either a wall or, in my family's case, el Río Grande, Hernández offers another border to consider in the Latinx identity concept: el charco or pond. In this case, the pond that separates the U.S. and Borikén is the Atlantic Ocean. Hernández describes this entremundo as “a place divided: our bodies on one side, hearts, and spirits in another." While Hernández offers us the idea of being divided through charco-crossing concept, Cantú provides a new conceptual identity as the sum of the various parts that come together to form tejanidad. Ultimately, Cantú and Hernández craft language to describe the hybridity and multiplicity of the Latinx experience. These terms are a blessing as they enable us to locate and identify ourselves and our experiences in the context of entremundoness, cierto o no?

Well, sis, I’ve come to the end of this letter, and I hope that what I’ve excavated about curses and blessings from the texts provides a prism to see the Latinx contributors' extraordinary works in your edited collection. What a joy to spend time in Los Ángeles writing this letter to you. Enveloped by the radiant West Coast sun and cool nights, these texts have transported me to think about the curses of coloniality, race/gender/class oppression, and disgust that have shown up in my life.

Most importantly, I walked away from reading these selections with an overwhelming feeling of being blessed because of my distinct entremundo Latinx identity—Black and Mexican. For decades, I’ve spent time recuperating my family histories and making sense of my entremundoness. These Latinx contributors remind me I’m not alone in traveling on this path. Thank you for your vision and intentional curation and for inspiring me to share my reflections.

Con mucho cariño, tu hermana de la luna,

Judy

All carousel images courtesy of Judy Pryor-Ramirez.

Judy Pryor-Ramirez is a clinical assistant professor of public service at New York University. She’s a feminist pedagogue inspired by scholars who open our imaginations to questions of power in the pursuit of justice. An interdisciplinary scholar, Judy teaches and researches leadership for social justice at the intersection of race, class, and gender. Her work is informed by academic study at Teachers College, Columbia University, and training at Rockwood Leadership Institute, Emergent Strategy Ideation Institute, and the Public Science Project’s Critical Participatory Action Research Institute.