Reggaeton Feminista: Perreo as a Tool for Self-Empowerment

Editors’ note: This is the second in a two-part series exploring the history and role of women within reggaeton. To read the first article, “In The Thick of Bad Bunny, There is Reggaeton Feminista,” click here.

—

There is a long history between reggaeton and perreo that has led this dance to become a powerful mechanism for liberation. From perreo to bellaqueo to now perreo combativo and neoperreo, the dance went through a period of censorship and derision before being recognized as today’s global dance and in the process, unleashing a new generation perreando for the revolution.

A Brief History of Perreo

Perreo goes back to the early beginnings of reggaeton, in that small nightclub in La Perla—The Noise. It’s 1992 and everyone is vibing to Latin hip hop, a mix that crossed borders from Panamá to New York City to the Caribbean, forming what was called underground in Puerto Rico and that led to today’s reggaeton, a term popularized by DJ Blass. Raperos are onstage with DJ Negro on the 1s and 2s, playing the beat and hyping up the crowd. The music is hard. Women are present, but the ones dancing are mostly men. The intensity of the masculine energy overwhelms the room, and the DJs knew it. Shabba Ranks’ dembow riddim made its debut in 1990, but it wasn’t until Smiley Wonder’s sample that it eventually took over the world. Now, the riddim that made underground more sensual enters the scene and once DJ Negro drops that needle and plays that tra tra tra, there is no turning back. Las mamis and los papis were grinding to what was an African-derived dance called…perreo! And they didn’t want anything else.

Perreo is kind of like twerking from Africa, kind of like Brazilian funk carioca, New Orleans bounce, or the Ivory Coast’s mapouka, but not exactly. Perreo, also known as sandungueo, is uniquely caribeño; its ancestral lineage connected to enslaved Africans who were forcibly taken to Puerto Rico. As a consequence of European colonization, the communal dances brought by Africans were transformed into heterosexual pairings, which eventually influences perreo. Starting in the 1990s, however, perreo became increasingly misogynistic, sexist, and homophobic—not because the music influenced the culture, but because the music reflected it. As reggaeton developed from an expression of socioeconomic circumstances rooted in hundreds of years of colonialism, the music increasingly grew to be seen as a commodity. By the year 2000, more and more artists realized sex sells and the genre was penetrated with super sucio lyrics that not only further objectified women, but treated them as scapegoats for the “culture.” Further, the visuals in the music videos were raunchy, vulgar, and over-sexed portrayals for the sake of sales, going so far as to show naked women.

The tipping point for this oversexualization was “Qué melones,” a 2000 song by DJ Joe that talked about women’s breasts in an explicit way, comparing them to melons:

Quítate la camisa / Y también el brasier / Ponte de frente que de frente que te quiero ver / Porque quiero chequear / A ver si es verdad / Si son pequeñas o son grandes / Hechas o natural / Qué melones, mami qué melones.

This song created a subgenre of reggaeton and perreo called bellaqueo which comes from the Puerto Rican slang bellaco, which roughly translates to ‘very horny.’ On the dance floor, bellaqueo means to go beyond dancing with someone: kissing, touching, etc. In contrast to “Qué melones,” Ivy Queen’s 2003 classic “Yo quiero bailar” counters the narrative of women as sexual props for men to a liberated woman who asserts what she does with her body:

Yo quiero bailar / Tú quieres sudar / Y pegarte a mí / El cuerpo rozar / Yo te digo: "sí, tú me puedes provocar" / Eso no quiere decir que pa' la cama voy.

These stark differences showed the tension and struggle between genders and sexuality in reggaeton that would eventually transform the music and how perreo would be perceived and used today.

What began in the ‘90s with conservative governor Pedro Rosselló continued in the early 2000s, when perreo and reggaeton went through a censorship and criminalization campaign by the Puerto Rican government, which called its music videos “pornographic.” The police would raid homes to confiscate tapes, including the home of DJ Playero, the mixtape and music video guru at the time. The constant news of this aggressive two-year campaign in newspapers and magazines included headlines that helped popularize both reggaeton and perreo even more. As the campaign ended in 2003, its leader, Senator Velda González wasn’t reelected and the government gave up on its attempted censorship, settling for helping to strip away its blackness and create a more Latino, white-centric genre similar to the history of bomba and plena. Even so, reggaeton and perreo were cemented into history and a year after her crusade, the ex-senator was seen “swinging her hips” to reggaeton in San Juan.

Perreo Combativo

Dembow, a word in Jamaican patois, was constructed with an anti-imperialist mindset. A word that reminded Jamaicans not to bow down to their colonizers. However, ironically, the riddim that facilitates such freedom in the hips is also homophobic. Jamaican artist Shabba Ranks and others have long since apologized for the homophobia in their music, first, because of its translation ‘they bow,’ used to demean gay men who perform oral sex. Today, dembow’s original definitions have coalesced into a movement called perreo combativo.

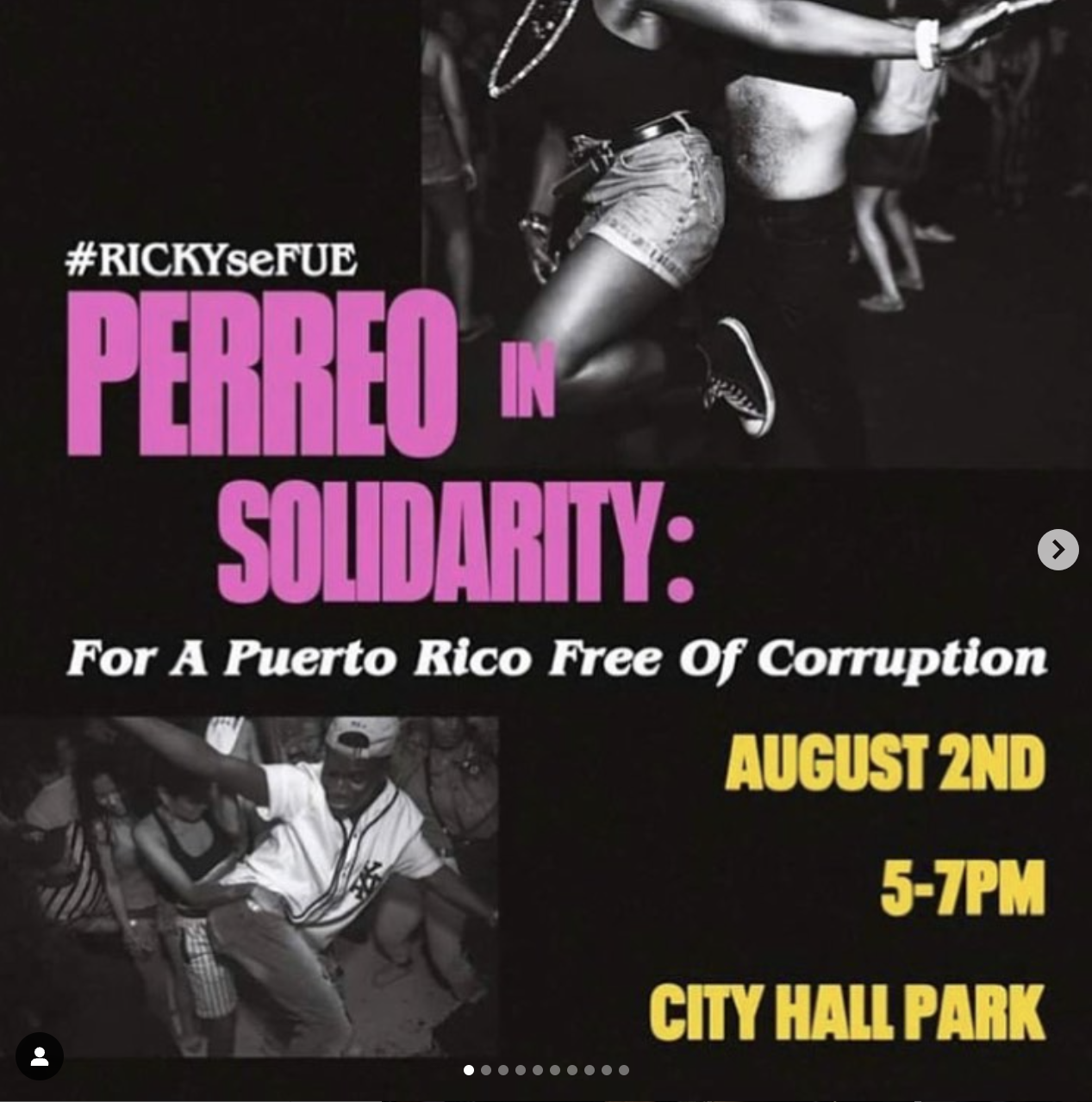

Perreo combativo, as defined in a Washington Post article, “was dubbed by queer, trans, and nonbinary youth…to create a sensuous and liberated communal space that generated political power.” This wave of repurposing the dance was born and visibly seen in the Ricky Renuncia protests.

The island engaged in large protests for two weeks demanding the governor’s resignation after 889 pages of texts were leaked in 2019 by the Puerto Rico-based investigative journalism nonprofit Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI). Then governor Ricardo Rosselló had made fun of those who died during Hurricane Maria, called New York City council speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito a whore, and mocked Ricky Martin’s homosexuality. Part of those protests were nightly perreos in front of the governor’s mansion titled “Perreo En La Fortaleza.” With reggaeton blasting, women, trans, gay, nonbinary, and people of all genders and sexualities grinded on the cobblestone streets of Old San Juan, promoting its slogan, “Sin perreo no hay revolución” and chanting “Ricky Renuncia el pueblo respeta este perreo es de protesta.”

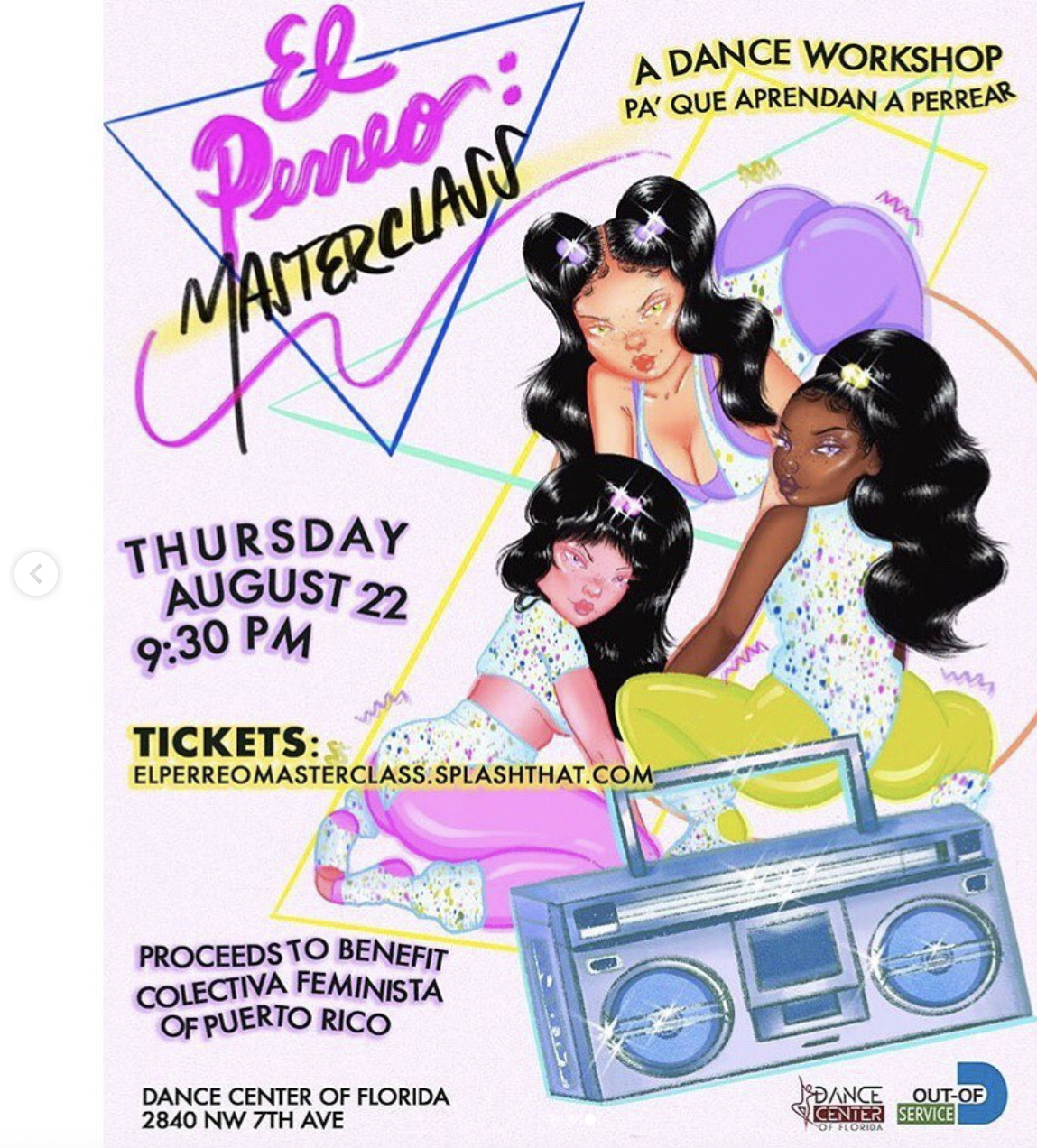

On July 24, 2019, in a full circle moment, the son of former governor Pedro Rosselló resigned. There was a twerkathon on the steps of the San Juan Cathedral, followed by a massive perreo combativo party the next day. Shortly in the aftermath of these protests, “perreo intenso” parties took place in cities like New York, Los Angeles, and south Florida in solidarity with the people of Puerto Rico. New York City parties such as “Perreo 2 The People” and “Abajo la colonia con mucho perreo,” Los Angeles’ “Grind For the Rights: Reggaeton Party” by Puerto Ricans in Action, and south Florida’s “El Perreo: Masterclass, a dance workshop pa’ que aprendan a perrear” are all examples of the ways perreo was used by the diaspora as political resistance.

DJ Bembona, who helped organize and played the music in some of the New York City perreo parties, expressed:

“These parties in New York were a sense of purging. A lot of parties, functions and actions were for the activists that were in the streets and at the forefront in the diaspora who were also protesting. To be able to come to a party to be able to purge was the most beautiful thing, to release all the things that were happening daily. Perreo was a big part of that and that is what perreo comabtivo did. It allowed people to express themselves freely on the dancefloor, whether that was tristeza, anger, as well as joy.”

For some, the parties were fundraisers to support one of the Puerto Rican feminist groups in the struggle, Colectiva Feminista En Construcción, an anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal, and anti-racist organization that called for the island’s national strike on July 18th and initiated yearly protests in front of La Fortaleza titled “Si no puedo perrear, no hay revolución.”

In talking to co-founder of Los Angeles-based Puerto Ricans in Action Nicole Hernandez, she says this about its reggaeton party:

“We always take our lead from Puerto Rico movement spaces to uplift, amplify, and support them. When it comes to the distance, she says ‘our effort is to bridge the divide between Puerto Rico and the diaspora and close the distance between us.’”

A year and a half after #RickyRenuncia, perreo combativo entered academia as a virtual panel discussion titled “Perreo As Queer Feminist Resistance: A Creative Conversation,” co-sponsored by the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Florida. Perreo combativo continues to be used as a resistance method against the continued oppressive tactics of colonization on the island, particularly during the protests against the contract renewal for LUMA. Perreo, additionally, has transcended borders beyond the island and U.S. mainland. Women and queer communities in Latin America and Spain are also using perreo in expansive ways for their own liberation work.

Perreo Beyond

Not only are there a slew of queer and trans reggaetonerxs on the scene, but there is also a collective of “patriarchy emancipatory” perreo parties and queer collectives similar to Puerto Rico’s El Hangar that have swept through Latin America, three in particular coming out of Mexico, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Mexico City’s Mami Slut was started in 2015 by two artists, DJ Travieza and La Mendoza, who consider reggaeton and perreo a decolonizing practice by reclaiming the dancefloor to not only move their bodies, but present themselves in drag and fashion that expresses their innermost selves.

The SinVergüenza collective was created in conservative Quito, Ecuador in 2017 by artists Joya and 5urdeaMarica who were also frustrated with the lack of non-traditionalist, safe spaces for the queer community. In a 2019 REMEZCLA article, they expressed that reggaeton is a way to decolonize themselves because the language used is not the “correct” Spanish promoted by elitism. Furthermore, the music and dance facilitate pleasure through body movement, a form of resistance important to their liberation.

Motivando A La Gyal, its name inspired by Zion and Lennox’s 2004 album Motivando a la Yal, was founded in 2017 in Medellin, Colombia by transfeministas, similar to the abovementioned groups, to find solace with likeminded people in a safe space for people of all genders to talk and share knowledge with each other.

In full-on irony, perreo has also swept parts of our colonizer country, Spain, particularly the capital of Madrid. In a 2019 documentary short by Boiler Room, the women, queer artists, and DJs interviewed agree that a common connection between the current generation is the suffering of their grandparents from the Franco dictatorship (1930-1961). Consequently, the grandkids are living through a “liberal anarchy,” with reggaeton and perreo at the forefront of a cultural movement resembling La Movida Madrileña during their parents’ time in the 1980s post-Franco era.

All these movements in reggaeton and perreo have also influenced another version called neoperreo, a term dubbed by Chilean reggaeton artist Tomasa del Real. Neoperreo is influenced by the digital era and made by artists who are willing to bend the genre into something that is made for everyone, not just for women to perform for men. Tomasa in 2016 for REMEZCLA explained:

“#NEOPERREO is a synthesis of all these new sounds, of the new consumers who include people from the majority as well as the minority, where we all come together through el gusto de bailar.”

From misogynistic and homophobic roots to a liberatory and self-empowerment tool, perreo has leaped into the future thanks to the women and the LGBTQAI+ communities who have expanded its potential in the United States and Spanish-speaking world. If the genre can help bring down a governor in Puerto Rico, we can only imagine what else it can do.

Damaly Gonzalez is a Brooklynite, Williamsburg-native of Puerto Rican descent that goes by she/her/hers. She is a culture and identity writer who writes ideas, opinion, and analytical pieces by using stories of everyday life experiences in order to invoke deep conversations and conscious minds. She has been published in Latina Media Co., NACLA, The Latinx Project at NYU, NBC Latino, and others. Damaly holds a master’s degree in History and Urban Sociology from The Graduate Center, CUNY. Follow her on Instagram @damalyscorner or Twitter @damalygz.