Regenerative Casitas: Eternal Works in Progress

Regurgitated concrete and glass buildings can easily plasticize the backdrop of New York City. However, Puerto Rican communities have agitated the archetypal linear city grid through casitas that have reframed notions of what constitutes a home. If you were to Google “casita,” the first definition provided by the search engine states that a casita is “(especially in the U.S. Southwest) a small house or other building.” Even though this definition emphasizes a domestic quality and scale of the building type, the formless “other building” clouds nuanced understandings of spaces that are not bound by four walls.

Puerto Rican casitas in New York City have historically been one- to two-room wood frame structures reminiscent of houses in Puerto Rico’s working neighborhoods.¹ However, casitas are dynamic architectures; their one-of-a-kind spatial compositions, material make-up, and social programming have prevented them from fitting into a conventional building typology. Casitas provoke an expanded interpretation of what a home is for communities that are neither here nor there but instead somewhere among the physical, mental, and spiritual.

Many islands make up New York City. The liquid memories of their inhabitants sustain a few of these islands afloat. Deeply rooted in a sense of place, the casitas they created emerge as architectures of resistance² that transpose embodied knowledge into continuous elements woven into the urban fabric. Within ruptured cityscapes, they stitched together communities separated by 1,614 miles of sea and transformed concrete crevices of the city into lush community retreats that have assembled spaces of regeneration.

Walking through once-maligned neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side or Williamsburg now, it seems unimaginable that abandoned buildings and vacant lots once permeated streetscapes. Within urban fissures, casitas emerged as centers of recluse and relaxation for local communities facing displacements and dislocations. However, aggressive urban developments and planning legislations have rendered casitas invisible, transforming many of these sites into market-driven high-rises, radically changing local ecologies. From a bird’s eye view, it might seem as though these practices uprooted casitas from the land. However, they remain integral sites for Puerto Rican communities throughout the city, who have designed, built, advocated for, and preserved these spaces—even if their structures no longer physically exist.

“When they arrived in the United States, their positionality as second-class colonial subjects inevitably affected their relationships to labor, capital, and production. ”

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, thousands of Puerto Ricans migrated to New York City following the implementation of the economic strategy known as Operation Bootstrap in 1944. After failed attempts to convert the Caribbean island from a monocultural agricultural economy into a manufacturing destination for tax-exempt, U.S.-based corporations seeking cheap labor, many unemployed workers decided to move to New York City, where they could find low-wage manufacturing and service jobs. New migrants usually found work in factories and other strenuous venues that shadowed the labor conventions and rhythms of sustenance farms and plantations. Life as a factory worker, though removed from the harsh conditions of the sun, did not operate on a completely different wavelength than working the land. The cyclical nature of doing and undoing that traveled with these workers could have easily enervated their bodies.

When they arrived in the United States, their positionality as second-class colonial subjects inevitably affected their relationships to labor, capital, and production. The harsh conditions that this status imposed on Puerto Ricans worsened because of the enactment of urban renewal projects and redlining practices that condemned and segregated BIPOC neighborhoods. Urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s, such as the creation of FDR Drive and Brooklyn-Queens Expressway by infamous urban planner Robert Moses, grazed BIPOC neighborhoods with top-down infrastructures that divided communities and spurred pollution. Though the city promoted these infrastructural projects as modern architectural and transportation interventions, they generated fissures within urban landscapes.

The gaps that resulted because of the chronic disinvestment, prompted by predatory renewal projects and zoning ordinances, generated an abundance of vacant city plots that ended up as destitute sites. In response to this, members of the Puerto Rican community took it upon themselves to reimagine blighted urban environments to sustain healthy local ecologies. By reclaiming vacant lots that machine politicians and developers once ignored, casita architects reconstituted their communities’ well-being within the city fabric and designed essential social infrastructures where people could despejar la mente y relajar el cuerpo. Casitas defined a familiar home in uncertain cartographies. By remediating toxic spaces on the edges, the seeds of those en la bregadera were cultivated as integral fruits of the city’s topography.

As Puerto Ricans moved from the tropical archipelago to New York City, they also brought building techniques, styles, and place-making practices traditional to a Caribbean context. Casitas popped up as standalone structures whose unique forms stood out from the vernacular brick and concrete high-rise city. They echoed the design of traditional Puerto Rican bohíos, common dwellings in Puerto Rico influenced by Indigenous and African building styles, that rested on stilts and had palm wood exterior walls, topped with thatched roofs³. Community actions activated these material connections, thereby transforming the once-vacant sites into lively gathering spaces that hosted events such as craftsman workshops, lechón roastings, dance parties, and concerts.

Instead of constructing standardized structures that would confine social programming within one structure, casita architects radically reimagined environments on sites that needed rehabilitation. Self-help and mutual aid practices that were prevalent in Puerto Rico during the 1940s and 1950s made their way into the construction of casitas in New York City. To build casitas, members of the community had to clean vacant lots filled with debris and rework ground conditions to foster the growth of verdant landscapes that surrounded some casitas and eventually became thriving community gardens. Many casitas formed small circular economies as community members worked together to build them from locally found, recycled materials. Martha Cooper’s historic photographs highlight how casitas not only reflect the craftsmanship and thriftiness of their architects but also emphasize how each designer reinterpreted tectonic expressions. (In the late 1980s, Cooper photographed thousands of casitas; she is in the process of archiving her work at the Library of Congress.) By grounding their building practice within constrained sites, casita architects synthesized innovative structures that were literal products of their environment. The reuse of building materials allowed casita architects to continuously articulate new spatial compositions that expanded canonical perceptions of the Puerto Rican casita.

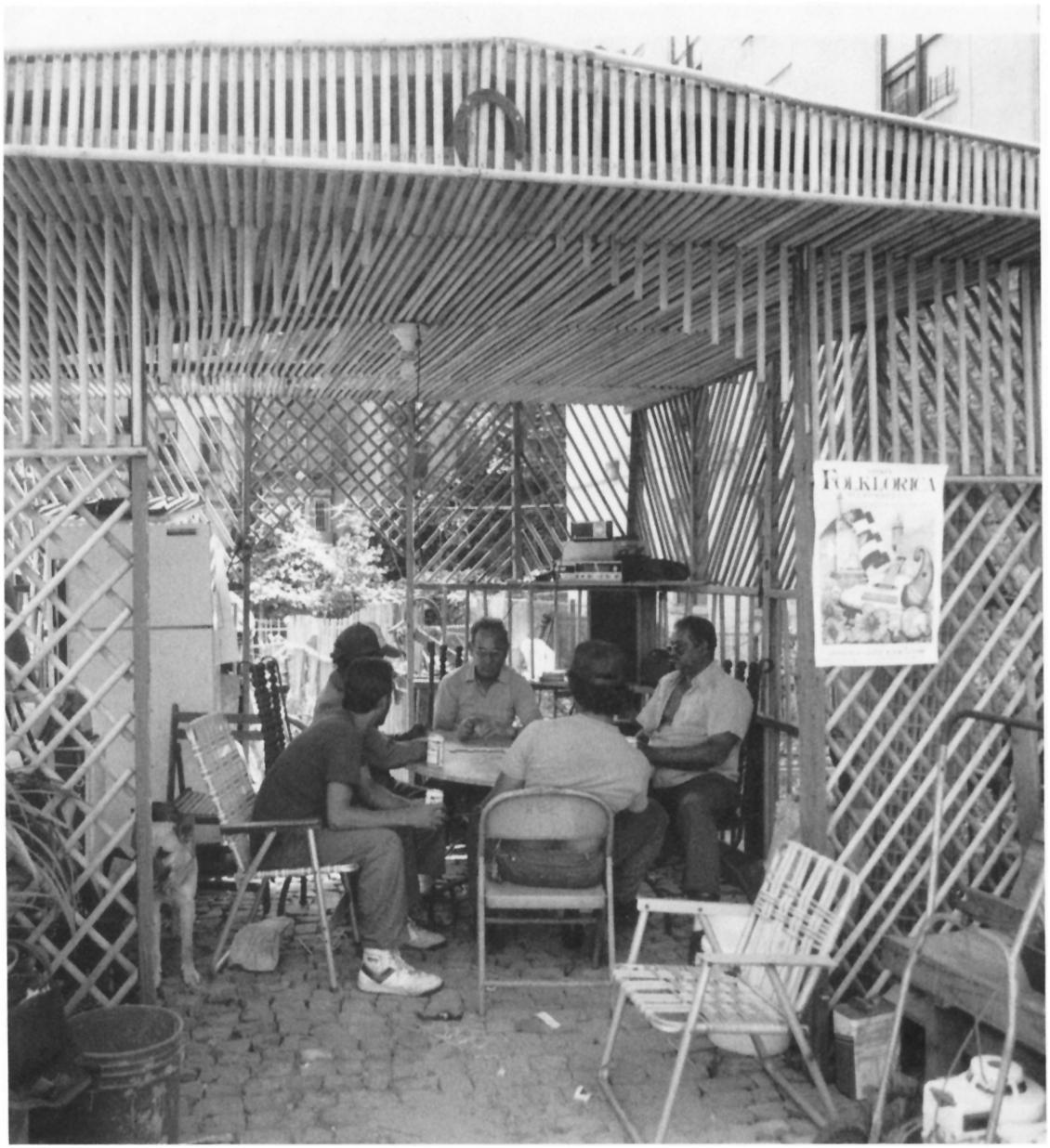

For example, Antonio Tirado made a casita in El Barrio out of broomsticks salvaged from an insolvent factory. The defining feature of Tirado’s casita was a lattice skin that blurred boundaries between interior and exterior space. No interior walls divided the casita, as it consisted of a primary central space whose programming could be rearranged by furniture and appliances. Its frame was not boarded with lumber planks or dry-wall; instead, its see-through patterned facades dematerialized an enclosure that reframed views and connections to surrounding environments that seeped through creating sonic and tactile environments.

Whereas Tirado’s casita appeared similar to a light pavilion structure, other casitas—such as the still-standing Casita Rincon Criollo in the South Bronx—expressed a more direct translation of rural Caribbean vernacular housing. Through its foundation, floors, walls, pitched roof, doors, windows, shutters, and balcones, its founder José Manuel “Chema” Soto manifested a contained house and extended its social theater outdoors. Through landscape interventions such as a concrete topographical map of his homeland that was sculpted into the earth and painted tree trunks that repelled insects as done in regions throughout the Caribbean island, Casita Rincon Criollo grounded historically dispossessed communities to the land.

In “Las Casitas: Oases or lllegal Shacks?” Joseph Sciorra, a folklorist who has studied the casitas, highlights how ''the sad fact is that casitas and community gardens are seen as temporary custodianship of neglected city property, and when the city finds it profitable to develop these properties, they are going to kick these people out.” City officials' bureaucratic view of casitas as neglected or illegitimate sites undermined the essential regenerative nature of casitas. Casitas replenished local ecologies and environments, as they emerged as literal ground-up spaces produced in la brega that tended to the needs and desires of a disenfranchised working population of the city. By creating “oases” within dilapidated and imperiled environments, casita architects produced socially necessary work that allowed local Puerto Rican populations to sustain their livelihoods. In their multifaceted forms, casitas express a response to the many invisible structures that subjugate daily life.

As I walk past countless construction sites throughout Brooklyn, I wonder what these new projects will look like upon completion. Though “Work in Progress” signs with renderings might offer an idealized representation of what is to be, an air of skepticism clouds me along with dust particles. Whether labeled an ambiguous residential, commercial, or mixed-use building, I can’t help but think about how these buildings will change local communities. Through collective bregas, we can learn how people have instilled rituals that allow them to regenerate within a city that can easily undo them. Casitas invite us to think how continual ground-up re-creation of spaces at a small scale can counteract predatory forces that sustain empires.

¹ Refer to Joseph Sciorra’s text in “I Feel like I’m in My Country”: Puerto Rican Casitas in New York City, pp 156.

² Refer to Luis Aponte-Parés, Casitas, Place and Culture: Appropriating Place in Puerto Rican Barrios.

³Refer to Luz Rodriguez-Lopez, Casas Jibaras: Anotaciones Sobre Arquitectura y Tradición en Puerto Rico.

Vanessa González is an architectural designer from Sunset Park, Brooklyn, whose work explores how ephemeral architectures can define cyclical regenerative spaces for communities. Recently, her research has been supported by the Butler Travelling Fellowship and the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, which has allowed her to continue her spatial investigations in Puerto Rico. Vanessa is currently a graduate student at the Princeton School of Architecture, and holds a B.A. in Architecture from Barnard College. She has previously worked at Joel Sanders Architect/ MIXdesign, Verona Carpenter Architects, and French2D.