Reappropriating Impositions: A Conversation with Gonzalo Fuenmayor

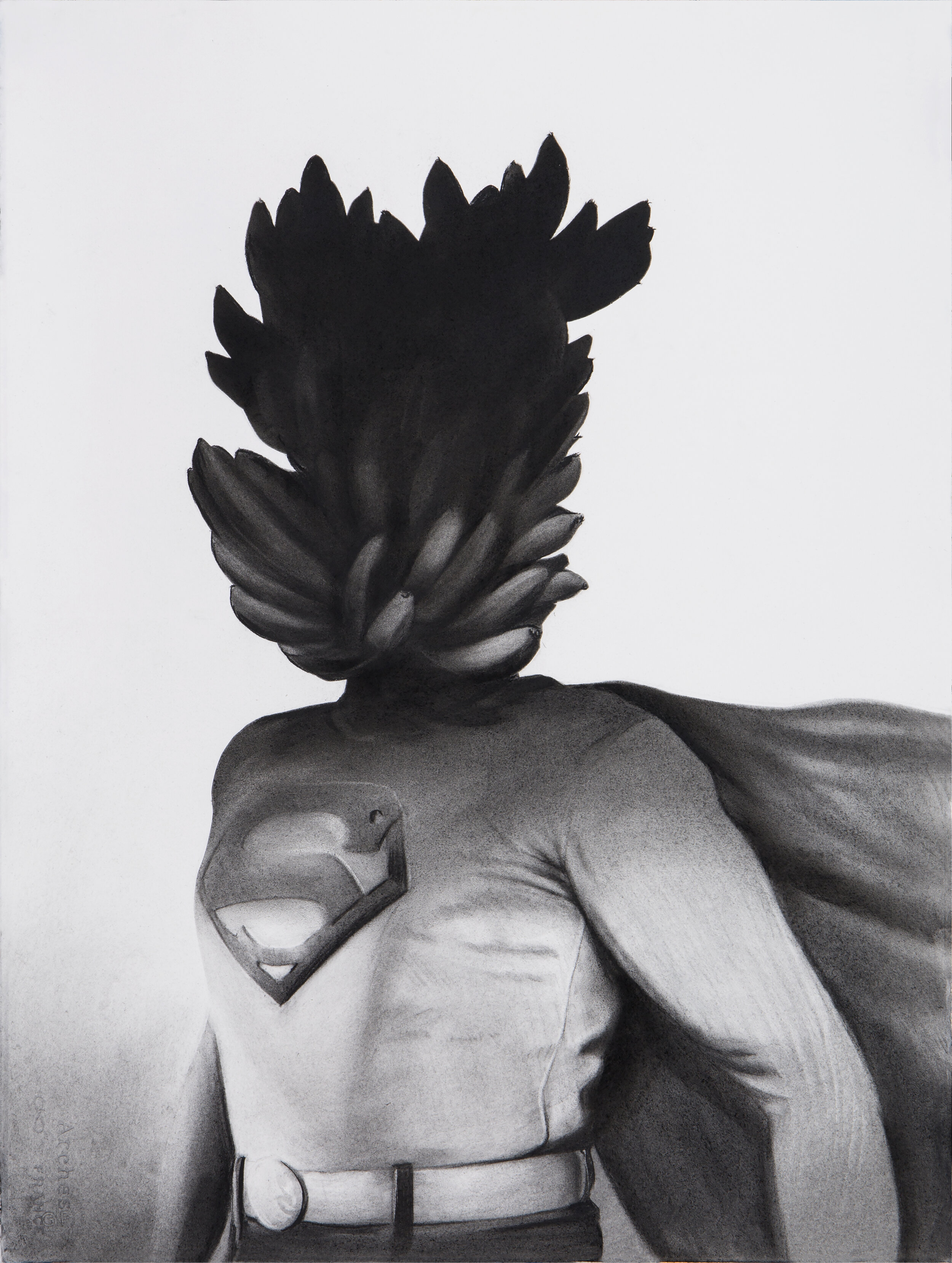

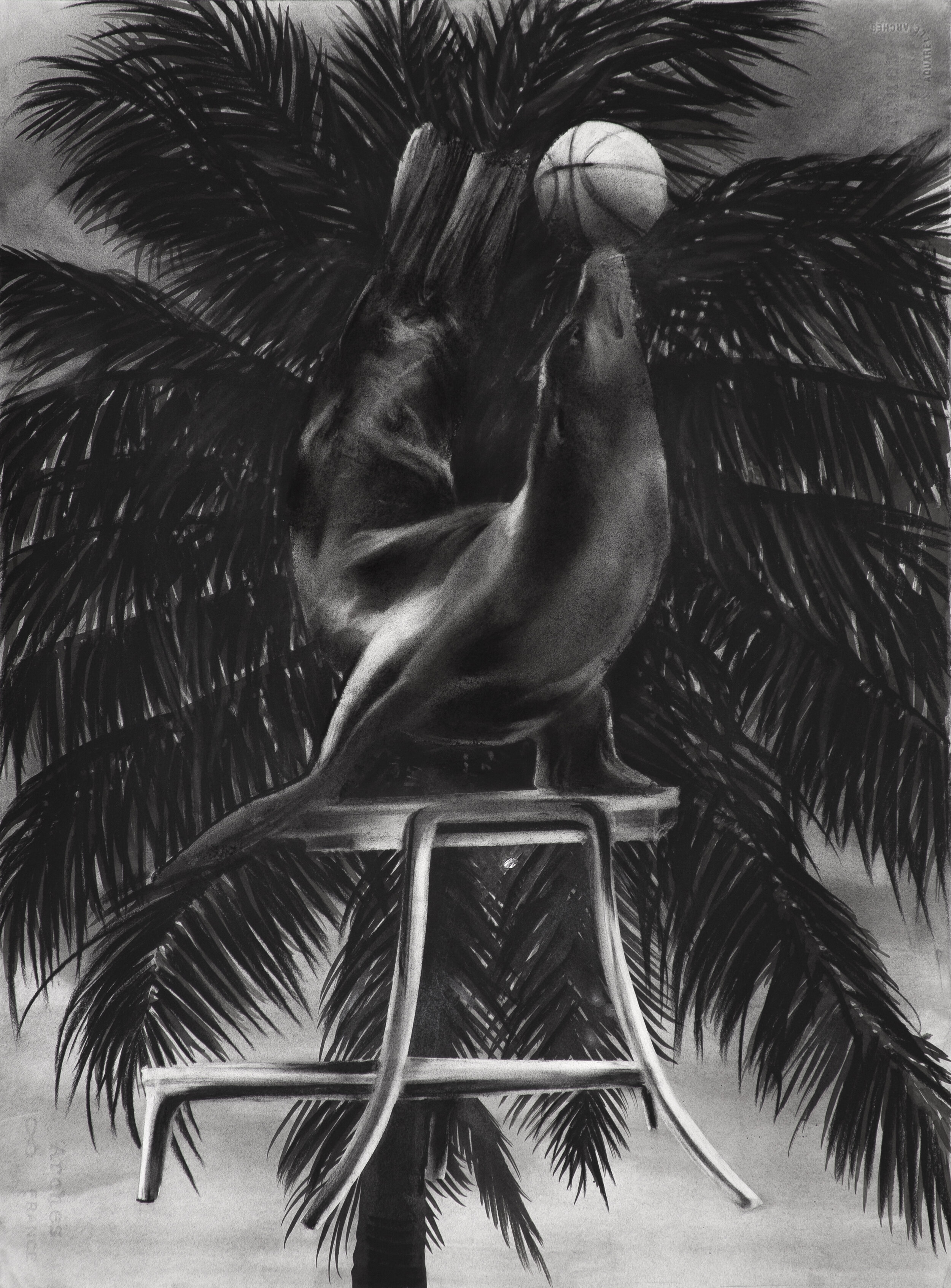

Gonzalo Fuenmayor is a visual artist based in Miami whose work addresses the history and socio-cultural context of identity and labor politics in Latin America, particularly as linked to the Colombian Caribbean and racialized bodies. Fuenmayor challenges the imaginary of a mythical locale often seen vis-à-vis the exoticization and hypersexualized tropes in which Colombian diasporic as well as Latin American artists in general are frequently pigeonholed. Fuenmayor’s work refutes at the same time that it reappropriates these exoticized impositions.

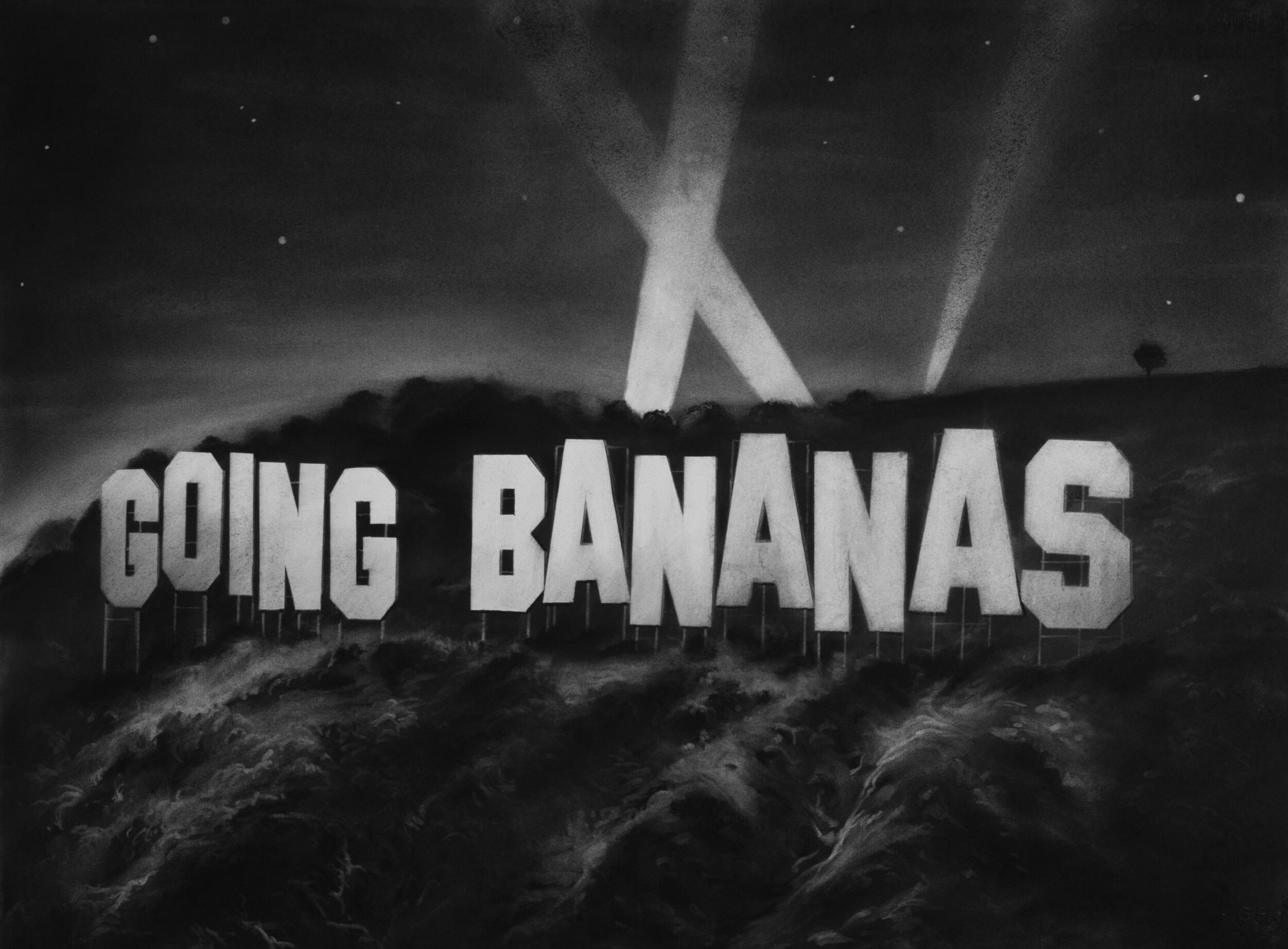

Fuenmayor’s work reflects our current reality as rooted in colonialist history and ideology. This amnesiac attitude towards the past is probably best exemplified by the viral reactions that were spun on social media to the recent domestic terrorist attack at the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. “This is how election results are disputed in a banana republic—not our democratic republic," were the words of former president George W. Bush, while #bananarepublic quickly began trending. Originally coined by short story writer O. Henry in 1901 to describe nations that were forced to become economically dependent on US imperialist presence through the United Fruit Company, the term “banana republic” has continued to be used as a derogatory term for nations in the Global South to characterize and caricaturize political instability. Fuenmayor, who has used the theme of the “banana republic” to reflect the false ideology of a superior US moral code, also took to Instagram to draw attention to the ironic attempt of using this term to emphasize a supposed US American exceptionalism.

In this interview, conducted in February of 2019 at the artist’s Miami studio, Fuenmayor discusses how ideology and history are principal themes in his work.¹ He also speaks about his evolution as an artist, how his works dialogues with the history of the Colombian Caribbean, the marginalization of that history within a wider national imaginary, and the use of signifiers such as the banana as representative of a colonialist legacy and imperialist existence in Colombia.

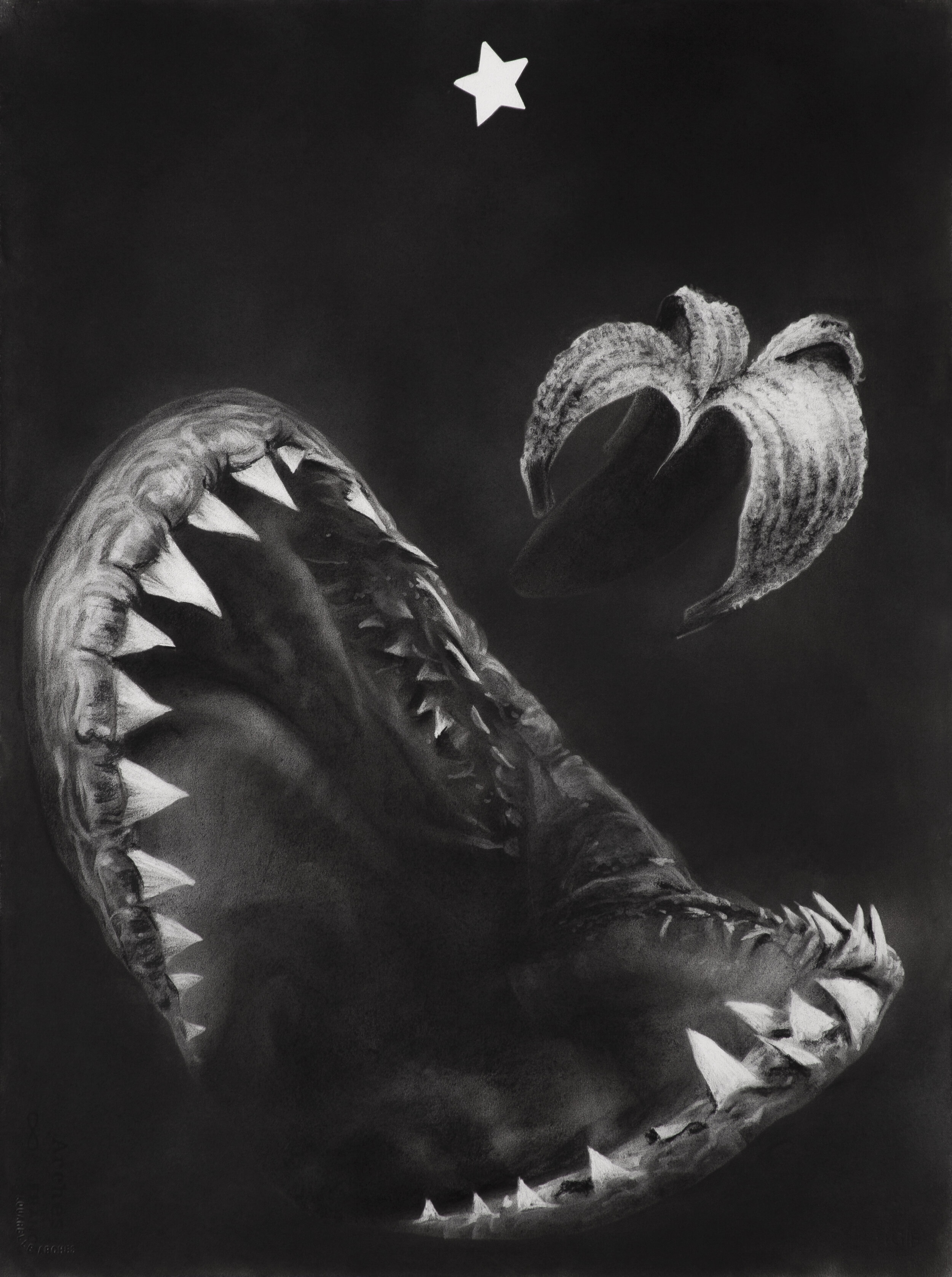

Annie Mendoza (AM): One of your works that I find fascinating is “La buena puntería,” which you painted in 2018. Were there any events or ideologies of violence that you connected with this work?

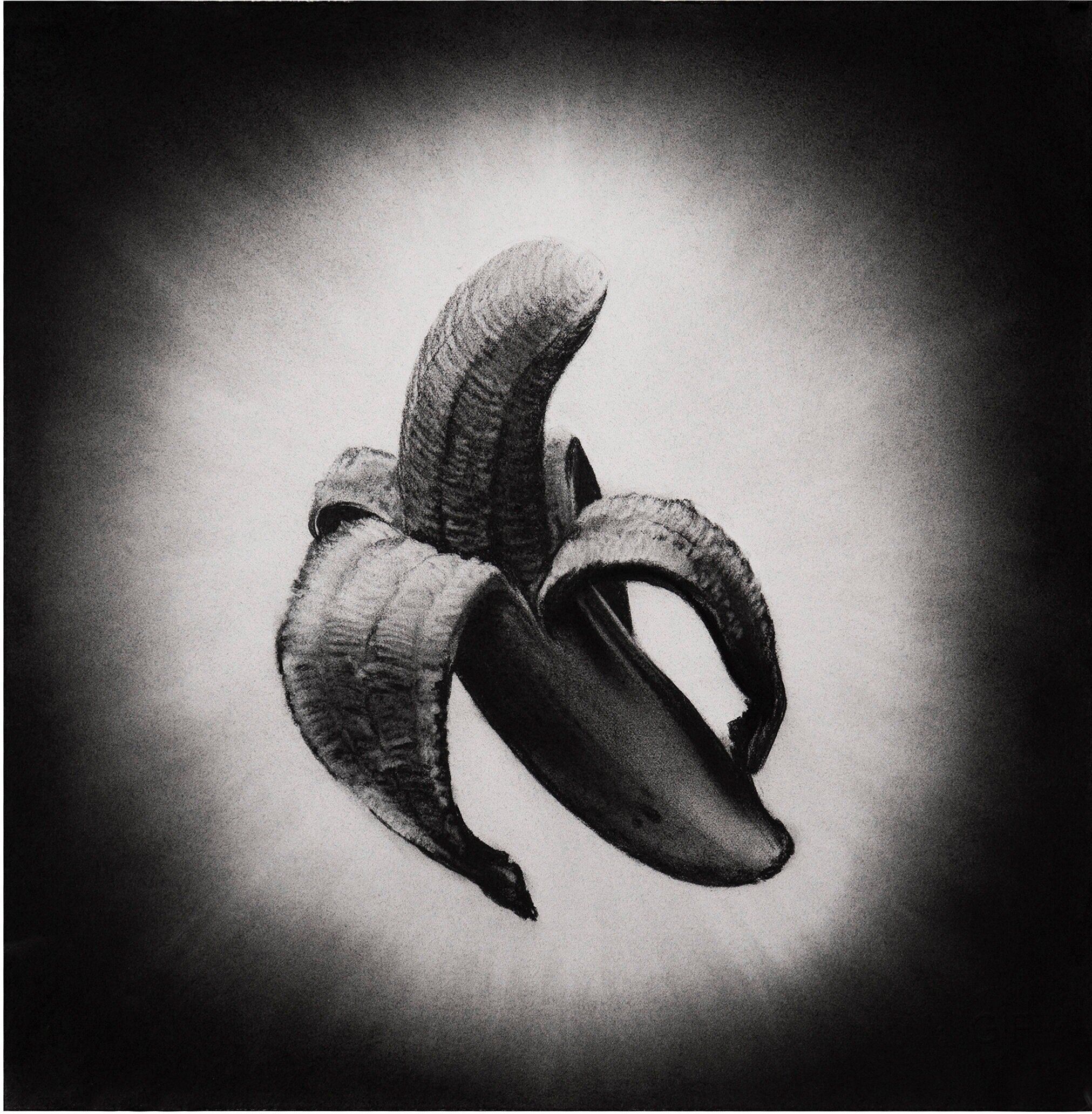

Gonzalo Fuenmayor (GF): Yesterday marked the one year anniversary of the Parkland massacre.² I remember when I began to create that piece, Parkland was very much on my mind. I had already been working with the image of the banana for quite some time, but I hadn’t used the banana as a weapon, in spite of the fact that, connected to that fruit, there is a whole historical context involving violence and weaponry. [“La buena puntería”] was a reaction to that [Parkland] event: a hand holding a banana as if it were a weapon is very poignant, at the same time that it is a very simple image. In my work, it’s not normally a single event that inspires one single work, but this event was different; it caused this reaction in me.

AM: And being that it happened in 2018, which was also the 90th anniversary year of the December 6, 1928 masacre bananera on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, could also contextualize this painting some more. We are in South Florida, the banana’s connection within tropical symbolism as well as within cycles of violence is undeniable.

GF: Yes, although I didn’t necessarily have the masacre bananera in mind in terms of the contextualization of this piece, the work in itself becomes a homage to all victims of violence. Making this work on paper was a way to deliberate over these events as a father of two young boys who were seeing the aftermath of this tragedy on the news. They would ask questions that were difficult to answer. This piece was my reaction; it was a way of exercising those fears.

AM: It’s notable immediately from your work, and being here in your studio, your sole use of black and white, and sometimes grey. In a Studio Shorts Video, you note how you arrived at deviating from color in order to get away from being caged as a “token Latino artist in the US”. Could you talk about this concept of being pigeonholed?

GF: When I began my MFA in Boston, my work was very figurative and there were some allusions to violence. I would represent the moment right before or after an act of violence: there would be blood, dead bodies or spaces in which some violence had taken place. I was one of few Latin Americans within my cohort, and it was a very white context. So whenever I said something that was a bit surrealist, immediately people would say to me: “Of course! Magical realism! García Márquez! You are identifying with the drugs and violence of your country.” I would see how they would classify me, according to certain things, and I was at a loss as to how to get out of that [classification]. I used to use a very colorful palette with very gestural figures; everything was very dramatic. So, I started to play with that stereotype that they were imposing onto me. I said, okay, I’m going to be that Latino artist par excellence that you are thinking about.

AM: You decided to reappropriate what they imposed onto you.

GF: Correct. So that began a process of “You know what? You want to exoticize me? I will exoticize myself even more for you.” So that’s when I started to play with the idea of One Hundred Years of Solitude and creating the Los Macondos series.

And so I started looking at the connection of magical realism with the identity of a country or culture with that concept. But at the same time I was still interested in color. I was very interested in how the Flemish painters used light and shade in a certain way. One anecdote related to this is that one day, I was painting at a summer school that I attended in Italy. It was a cloudy day and I was painting a landscape: houses, rooftops, all with pale rose colors. I painted the sky blue, and I was painting bright red bricks. The professor, who was U.S. American, said to me “You’re Latino, right?” And I asked why he asked. His answer “Well, look at the sky, that’s gray; but for you it’s blue.” So that was another moment for me that I realized there are so many idiosyncrasies imposed upon Latino artists. So I decided to modify the way that I represented reality. I started using only black and white in an attempt to not identify with those expectations imposed to one’s race or origin, and to try to create a shift wherein the focus would be more on the image. That was the beginning of my use of only black and white as my palette.

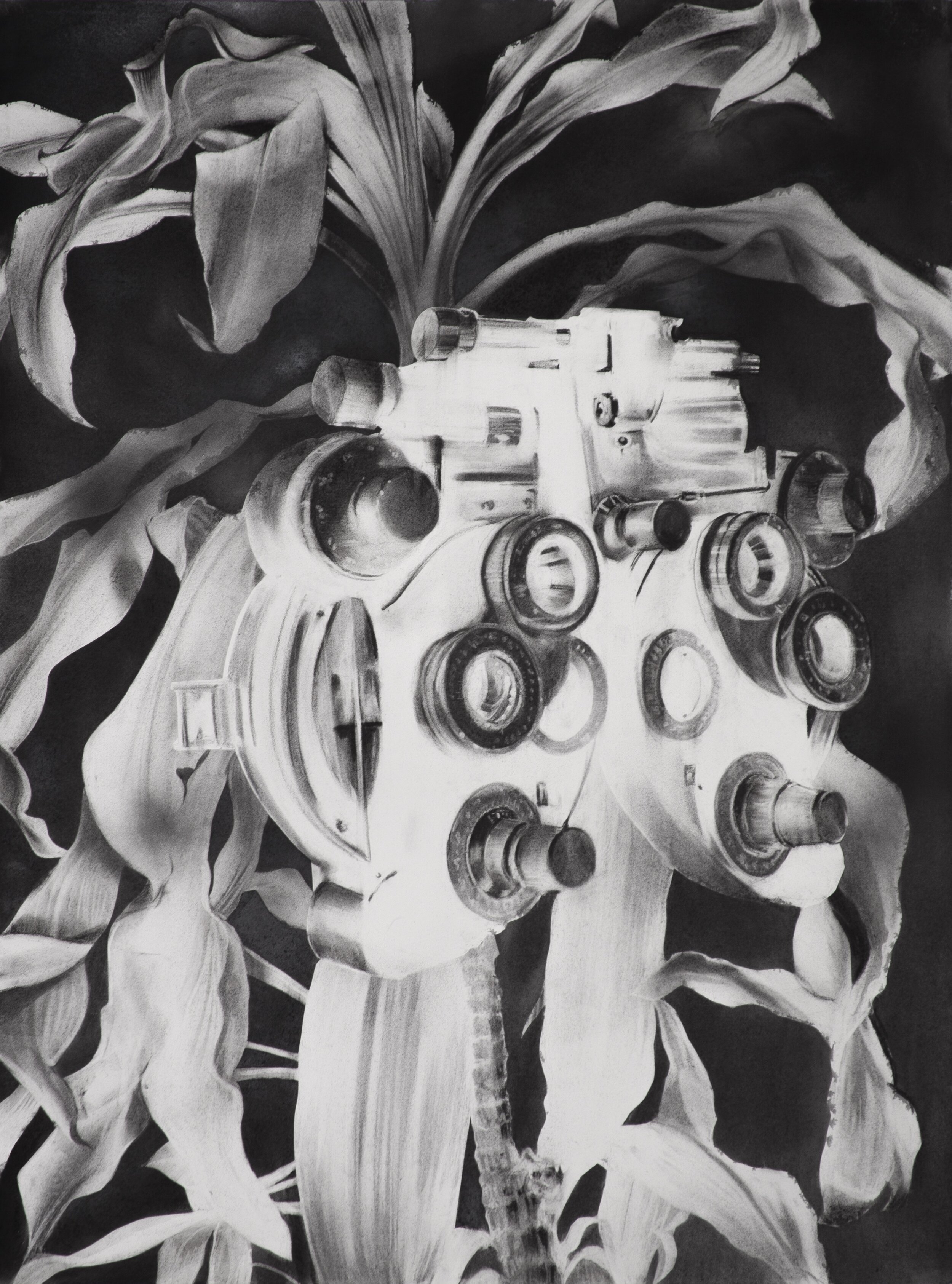

AM: Looking at these images here in your studio, I feel that by only using black and white, there is also something at play for the audience of the work, in that it makes one reflect more on the signifier: the exoticization of the place represented.

GM: Of course, and these places represented are exotic for me. This here is a play on [Jean-Honoré] Fragonard/18th Century French painting, this here is like a banquet at Buckingham Palace.

So what interested me from this era was the Decorative 18th Century Baroque architecture that was more confined to boasting about opulence of the empire at the cost of all of these relations that were invisibilized by the colonies. Colombia doesn’t have the same history of an extraction economy during the colonial period as was the case in Cuba, for example. But now, we are looking at the empire of the United States, of Europe. These clashes coexist and transform in unexpected ways. So these excessively decorative spaces that reinforce this idea of power and opulence that are so distinct to my reality, makes me constantly want to confront these spaces of power.

AM: Your chandelier series in the Papare (2013) project is so on point because the audience is forced to think about the blood of the Black labored body that was shed for the colonies in order to have this opulence exist.

GF: I agree. And it’s a labor that is camouflaged within this extravagance that doesn’t let you see past it.

AM: Yes. And I’m looking at this image here which reminds me of a queen.

GF: Yes, this image is a queen. First of all, in this new series of paintings I’m working on, I’m inverting values. Everything that would have light, is dark; and everything that would be shaded becomes the white of the paper. This is an image of the queen inside of this palace, but I’m flipping it so she appears to be of a different race. She is in the center point of the composition and she’s in the middle of the space of power. So it’s like taking these spaces that are very white, very European, and inverting the subjects via the light, and thus the power play is inverted and challenged.

AM: To continue with this theme of identity and representation, what do you think regarding identity politics in the United States as you’ve encountered it in your experience as an artist, versus identity politics in Colombia or Latin America in general?

GF: When I go to Colombia, right away my mother says to me: “Oh, you’ve become gringo.” In Colombia, I feel like I no longer have the skills of day to day life—being in a line at the bank, for example. This notion of auto-exoticization reminds me of Judith Butler and her theories on gender performance. I feel as though this performance is related [to identity politics in general] in that one thinks about how to exoticize oneself: as Colombian, as Miamian, as a woman, as a man… I think it’s a continued performance of how to be and who is looking at me. How am I this [category]? So, the performance aspect of identity has always interested me. Because precisely I used to find myself constantly translating from Spanish to English, even after being here for almost 20 years. My children were born here, we travel constantly to Colombia and we only speak Spanish at home. There is a process of assimilation and not wanting to assimilate to certain things, and understand how one is constantly negotiating this very blurry space between cultures. It’s something very intuitive. I’ve experienced this within my negotiation of how to belong to a place.

AM: Do you think these aspects are different in terms of your ability to express yourself as an artist and what you present and represent from place to place? Miami, versus Boston or New York?

GF: For me being in Boston was very formative because I embraced this attitude of: “Oh you want this from me? Well I’m going to give you this instead. Oh you want to talk about García Márquez and the influence of magical realism? Okay, I’m going to give it to you, but I’m going to put it in your face.” After a while, that tide began to die down, but nevertheless something from that time is important. And I became like the “banana artist.” Everything I did had bananas. I became the “Banana man.” I wanted to try to move away from that idea. Originally, the banana was a vehicle to address certain things, and I realized that it was mostly my relationship to being here in the US and answering: how to belong? So in Boston, being in a surrounding completely new to me helped me bring these ideas to visibility and embrace them. Here, in Miami, I’m able to embrace all different aspects of culture: high and low, Latin America and Europe, and thus it has been a very great experience to be here, because without being in Latin America, we are very close to Latin America.

AM: One thing that I find interesting to look at in all forms of artistic representation linked to Colombia and the Caribbean in general are how race, class, and dominant-culture power plays are handled and viewed. Could you comment a bit more on the representation of race, class, and other power structures in Colombia and the greater Caribbean as you see them in your works of art?

GF: Every time I return to Colombia I am more aware of how poverty and wealth live side-by-side in unexpected ways. When I went to do the Papare project on banana plantations in Ciénaga, I wanted to be with the workers and see the mythology surrounding the plantations as something exotic. It was important to see that it was not the same reality that we heard about before. Now there are regulations and rules as to how workers are treated. But nevertheless these spaces of power are very drastic in Colombia: very rich and very poor. And so I try to always find images that represent the clash of these different groups. My work navigates these different dichotomies between the plantation, the colonies, empire, wealth, and extravagance juxtaposed against different images that we see in our day-to-day life.

AM: That irony in itself, brings me to another link with auto-exoticization that I want to talk about and that we’ve touched on a bit: the association of Colombia with so-called magical realism. In our article that discusses your work, my colleague Tashima Thomas and I noted that on a plane heading to Barranquilla, you saw magical realism being used as a marketing slogan for tourism to Colombia. Could you comment on this magical realism marketing that emphasizes the ironies with Macondo/McDonalds, since the concept of magical realism has been used to actually downplay and negate real violence?

GF: Absolutely. This anecdote can comment on that: my grandfather was a very good friend of Gabriel García Márquez.³ When I was 13 years old, he took me to meet him so that I could ask him about the symbolism behind the rooster in his novella No One Writes to the Colonel (1961) for an essay in my literature class. I had so many questions and I felt I would get to the root of the true meaning of the rooster. All of my classmates and my teacher knew I was going to speak with García Márquez, and there were all these expectations attached to the symbolism of the rooster. When I asked this question—“What does the rooster mean?”—to García Márquez, he answered: “it means a rooster.” [We both laugh]. I was left like “What!?” So then, I started to feel at ease with a lot of things. I think this attitude of maintaining a reverence towards certain things is very common in the Caribbean. So then, these ideas associated with magical realism were already at play for me when I sat down five years ago on that plane ride to Colombia and saw that marketing; it made me think “Wow!” This is the same process that I went through: how does one auto-exoticize oneself to the world in order to not talk about certain things? The slogan added “the only risk is wanting to stay.”

AM: Really? The word “risk” was part of the slogan? In an attempt to move the signifier away from any connotations of violence, drugs, etc. How interesting.

GF: Exactly! I thought it was clever. I started thinking that if Colombia had an identity, it would be doing the same thing I had done: they were in a position of auto-exoticization to the world. I identified with that struggle, and I understood it. I lived in Colombia during the height of the violence [1980s and 1990s], where we were all trying desperately to look at other aspects of the country as positive and look for examples of national self-esteem: which Colombian is succeeding in Hollywood? Harvard? What about our biodiversity? We had this need to look for something that would emphasize “we are not so bad after all.” I feel like that plays along with the notion of expectations, there’s always a desperate attempt to look for the best way to present oneself. That idea has been part of my body of art for a long time. What is our national identity? How do we look at ourselves and how do others see us?

AM: Yes, so the golden arches of Macondo could be a great example of that.

GF: Yes, effectively it’s the McDonaldization of the concept of magical realism with Macondo. But it’s an empty concept because there is a lot left to close that cycle.

AM: Related to that notion of marketing and image creation, in the Papare project, I like how you describe this work as the “idea[s] of exoticism and the complicit and amnesic relationship between ornamentation and tragedy.” Can you discuss this more? Do you think this is something that is more prevalent in post-colonial and imperial spaces?

GF: Absolutely, there is an attitude of: how do I relate to the other? Everyone does it to some degree, whether you have power or if you are on the other side. Now these ideas come and go because of the internet, because of how easy we can communicate with others, because now images are more preeminent than real life. So now things are more problematic because power can exist in many ways.

AM: Yes, I thought it was interesting that you note the “amnesic relationship” because the 90th anniversary of the masacre bananera was only a few months ago [December 2018], and there was no buzz like I thought there would be. Some scholars did indeed have discussions about it on social media, and some Colombian newspapers devoted some attention to it as well. But there was not as much consideration given to it in mass media as I had expected, especially given the attention to those events in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Do you think this “amnesic relationship” happens more so in Colombia than other places?

GF: I think every country does this to some degree with their historical traumas. But I do think that Colombia has a certain relationship to el olvido that is distinct compared to other nations. In many countries, monuments are established, and there is a relation to the past. I feel Colombia has a more chaotic relation to the past and to pain: there is no one perpetrator of the pain of the past.

AM: I always think that because the story of the masacre bananera pertained to the Caribbean region, it was therefore not allowed to be a part of the national Colombian imaginary; there is a denial of that past and that it pertains to all of Colombia, although it was the first moment of imperialist violence that started a wave of violence in the twentieth century, because even [Jorge Eliécer] Gaitán rose to prominence in an attempt to defend the victims of that tragedy and to work against an imperialist presence.

GF: Correct. My maternal grandfather worked at the United Fruit Company. And as we know so many people—Gabriel García Márquez, Álvaro Mejía, amongst many, many others—wrote about this tragedy. Some people talked about these images of trains that threw out cars upon cars of cadavers. Some people said only nine people died, my grandfather said no pasó nada. This is where the magical realism comes in: there is a myth surrounding these events. So we go back to this idea of who is right? Nevertheless, there has always been a disconnect between the Caribbean and Colombia: the Andes versus the tropics within the history of Colombia.

Fuenmayor’s current solo exhibit Palindromes is on display through March 5, 2021 at Dot Fiftyone Gallery in Miami. In this video, Fuenmayor discusses the meaning of Palindromes. Find out more about Palindromes here and here.

Author Notes

I interviewed Gonzalo Fuenmayor in his Wynwood, Miami studio on February 15, 2019. The interview was conducted in Spanish. I have translated my questions and his answers into English.

This interview took place the day after the one-year anniversary of the Parkland massacre, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, on February 14, 2018. Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School is located about 45 miles north of Fuenmayor’s Miami studio.

Gonzalo Fuenmayor’s grandfather was Alfonso Fuenmayor, one of the founding members of the Grupo de Barranquilla literary tertulia that was created on Colombia’s Caribbean coast in the 1940s, and that included Gabriel García Márquez.

Gonzalo Fuenmayor (b. 1977, Barranquilla, Colombia) is a Miami-based artist working primarily with drawing. Fuenmayor has been concerned about the effects of modernization and progress not only on natural environments, but mostly on Latin American culture and its ways of being displayed internationally through stereotypes and common places. His aim seems to be not exclusively, to denounce banalization but also to understand its aesthetic mechanisms and cultural power. Fuenmayor received an MFA from School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA in 2004, and a BFA in Fine Arts and Art Education from School of Visual Arts in 2000. Fuenmayor has been awarded numerous awards including the 2020 EFG Bank Latin American Award, a 2018 Ellies Creator Award, a 2015 South Florida Cultural Consortium Fellowship for Visual and Media Artists, and a Traveling Fellowship by the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2014, among others. He has exhibited in numerous solo and group shows in USA, Latin America and Europe; his work was recently showcased in The Florida Prize 2018, Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, a solo exhibition “Tropical Mythologies” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2015, "Caribbean Crossroads” Exhibition at the Queens Museum, NY, as well as a recent solo show Palindromes at Dotfiftyone Gallery in Miami. His work is part of numerous private and public collections including Perez Art Museum Miami, Miami, FL, USA, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA, The Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Winter Park, USA among others. He is a current resident at Oolite Arts Residency in Miami and is represented by Dot Fiftyone Gallery, Miami, Dolby Chadwick Gallery, San Francisco, Fernando Pradilla Gallery, Madrid and El Museo Gallery in Bogotá, Colombia. Follow Gonzalo Fuenmayor on Twitter and Instagram.

Annie Mendoza is an Associate Professor of Spanish in the Department of Modern Languages, Philosophy and Religion at East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania. She received her PhD at the University of California, San Diego in 2010. She is the author of Rewriting the Nation: Novels by Women on Violence in Colombia (AILCFH, 2015) and has published essays in peer-reviewed journals such as Revista de Estudios Colombianos, Zapruder World: An International Journal for the History of Social Conflict, Voces del Caribe: Revista de Estudios Caribeños and the anthology Poemas y cantos: antología crítica de autoras afrodescendientes de América Latina. Mendoza’s current book project is on Colombian diasporic representations in literature, film, and theater.