Radical Remembrance: A Latinx AIDS Monument in Los Angeles

Last year the rapid spread of a novel coronavirus paralyzed the nation. While many lost loved ones to COVID-19, the pandemic disproportionately affected Black and brown communities. For many queer men of color, this was a painful reminder of another virus that devastated the LGBTQ community.

Nestled in the heart of Lincoln Heights, an eastern Los Angeles neighborhood made up primarily of working-class Mexican Americans, stands a monument to commemorate the lives lost to the AIDS epidemic that continues to disproportionately impact queer Latino men. The Wall Las Memorias AIDS monument, the first publicly funded AIDS monument in the nation, contains the names of more than 360 people who have died from AIDS, including the names of many Latinos from the surrounding neighborhood.

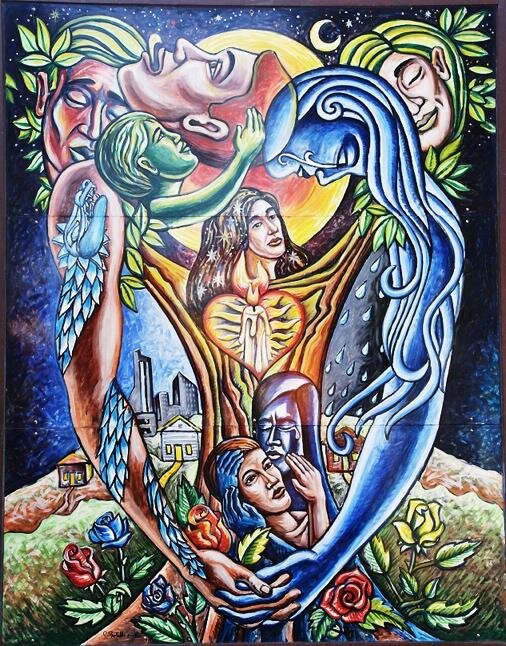

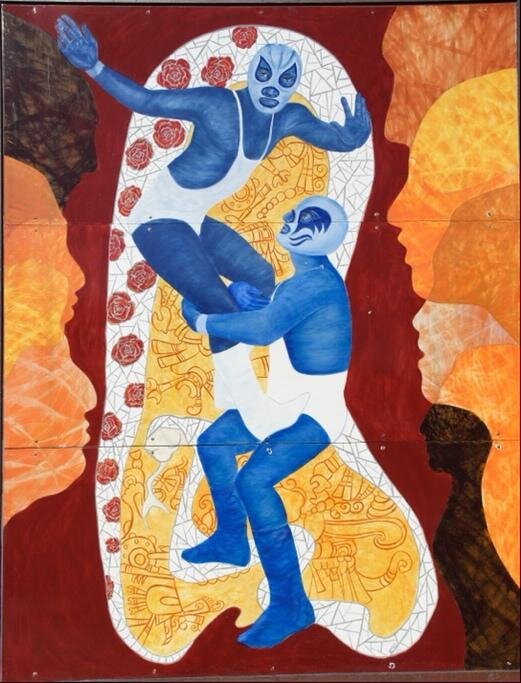

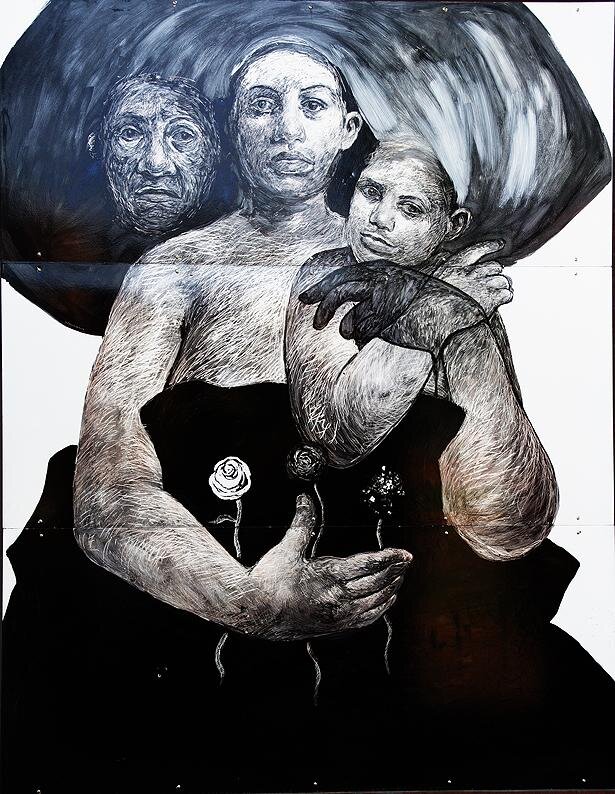

Designed in the shape of a Quetzalcoatl serpent, the Aztec symbol for rebirth, the monument consists of eight wall panels: six murals depicting life with AIDS in the Latino community and two panels containing the names of individuals who have lost their lives to AIDS. The artists include Yolonda Gonzalez, Miguel Angel Reyes, Pauolo Botello, Hugo Crosthwaite, Alex Alferov, and Kathy Gallegos. Many of the artists came from Self-Help Graphics in Boyle Heights, a community arts center that became a center for the Chicano Art Movement, providing training for many local artists that would go on to gain international prominence.

Although I remember hearing about the AIDS epidemic when I was younger, I thought it was an event situated firmly in the past. Growing up in a small conservative town in Texas, there was a silence that permeated the discussion of gay sex. When I became sexually active as a teenager, the possibility of contracting HIV as a young queer Latino was never on my mind.

“The younger population can’t relate to AIDS because they never had to live through the worst of it,” Richard Zaldivar, founder and executive director of the Wall Las Memorias Project, said. “You have the younger generation feeling invincible, thinking that they don’t need to learn about HIV prevention because it’s not going to happen to them.”

Yet, among gay Latino men, rates of new HIV infections continue to rise. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Latino men make up 27% of new HIV diagnoses, with 1 in 6 Latinos with HIV unaware they have it. Although there is effective treatment for those living with HIV to live a similar life expectancy to an HIV negative person and existing prevention treatments (known as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PREP), many gay Latino men do not have access to the services needed to address the disproportionately high HIV infection rates among gay Latino men.

Although there was initial opposition to the building of the monument with some opponents fearing it would attract “too many gay men” to the neighborhood, one of the earliest supporters was the group Mothers of East L.A. (MELA), a group of Latina mothers who organized in opposition to the building of a prison in Boyle Heights in 1986. With the group’s history of grassroots activism in the community, Zaldivar reached out to them to help galvanize the neighborhood in support of building the monument. During a city council meeting, the opposition, made up primarily of conservative groups, used homophobic slurs and handed out flyers protesting the monument’s construction.

“We had to have the police escort us out of the meeting,” Zaldivar said. “We were getting death threats every day. Even the Sierra Club [an environmental group] opposed us because they said we would take up park space to build the monument.”

One of the original panels designed by Alex Alferov, who had lost close friends to AIDS, incorporated elements of a Day of the Dead altar with the image of the Virgen de Guadalupe. It was intended to reflect the existing murals found in East Los Angeles; however, critics, including members of Defend the Family International, believed the use of the Virgen de Guadalupe glorified the “homosexual lifestyle” and was encouraging an “anti-religious” environment in the community.

Instead of becoming embroiled in costly litigation that threatened to jeopardize the entire project, the decision was made to withdraw the mural and replace it with another panel by Alferov that would pay homage to the children who lost their lives to AIDS.

Through the support of the Mothers of East L.A. that would show up at the city council meetings, some local catholic groups, and prominent Latinx politicians, the monument was finally constructed in 2004. For Zaldivar, one of the most tender moments came when he saw Latina mothers find solace and closure with the monument.

“I saw a lot of the mothers run up to the wall where their son’s name is and touch the names,” Zaldivar said. “There’s no greater love than that between a son and mother, especially a gay son.”

For Luis Valencia, a queer Latinx artist that lives in the neighborhood where the monument is located, the monument art style pays homage to the legacy of Mexican muralism that would go on to inspire the Chicano art movement of the 1960s.

“The muralist art was made to be a break from Western Renaissance art and unique to Mexican and Chicano art,” Valencia said. “Murals are made to tell a story of the community for the community. People can relate to it and see themselves in it.”

The murals included in the monument tell the story of those who lost their life to AIDS and acknowledge that painful history, one which is not often discussed in the Latinx community.

“Growing up in Los Angeles, AIDS wasn’t talked about in my family, so I didn’t know that Latinos were dying of AIDS,” Valencia said. “You would hear about Keith Haring and other prominent white figures who died of AIDS, but you would never hear about other marginalized groups who were also dying from AIDS.”

For Valencia, the monument challenges the dominant narrative of AIDS as just affecting gay white men. It sheds light on the devastating effect it had on the Latinx community who also form part of that larger history. Valencia believes it can also stand as a reminder for the younger generation to learn about an issue that continue to impact our queer Latinx community.

The space has now evolved into a community space, with the gardens surrounding the monument being used as the backdrop for some quinceñera photos and elders using the garden space to practice health and wellness. Although HIV rates continue to rise among gay Latino men, HIV is no longer the death sentence it once was during the height of the AIDS epidemic. With the emergence of preventative treatments and effective treatment options for those who are living with HIV, improving access to testing, treatment, and challenging the cultural stigma surrounding HIV in the Latinx community, the rate of new infections can begin to decrease.

I live just a couple of blocks from the monument. Now in my 20s, I pass by the monument every day on my way home and think about the stories of those people who lost their lives to AIDS. Their lives were erased and often forgotten; their stories silenced.

“There are so many people out there that haven’t submitted the names of loved ones who have died of AIDS,” Zaldivar said. “Either because they haven’t dealt with the issue or haven’t come to terms with the loss of a loved one who was gay or died of HIV.”

Through the power of community, the names of some of the queer Latinx people who lost their lives to AIDS are not forgotten. Whether it’s dealing with issues of homophobia or the cultural stigma against those living with HIV in the Latinx community, the monument stands as a testament to the resilience of the Latinx community and our capacity to come together and build a space that allows for a deeper understanding and engagement on an issue that continues to impact our community.

Jorge Cruz is an incoming PhD student in Chicano/a Studies at UCLA and received his master’s degree in Latin American Studies from Cal State LA. His research explores queer representations in Latinx art. He was also a summer intern at the Latinx Project.