Queerness and Blackness in the Archive: An Interview with Felicita “Felli” Maynard

“What we have lost as African-diasporic people, as Indigenous people, as queer people, as trans people, and as undocumented people is memory. We have lost our memory.”

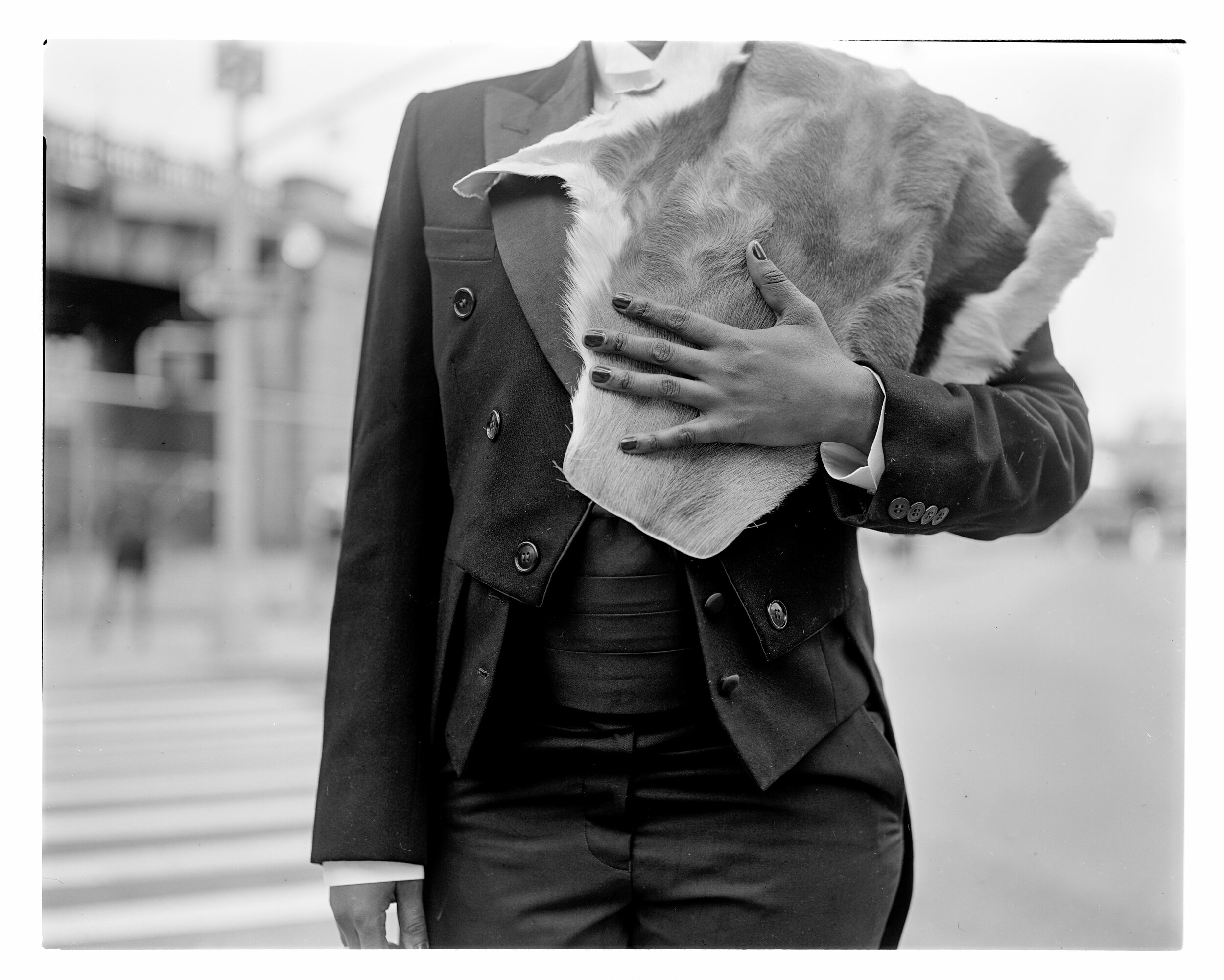

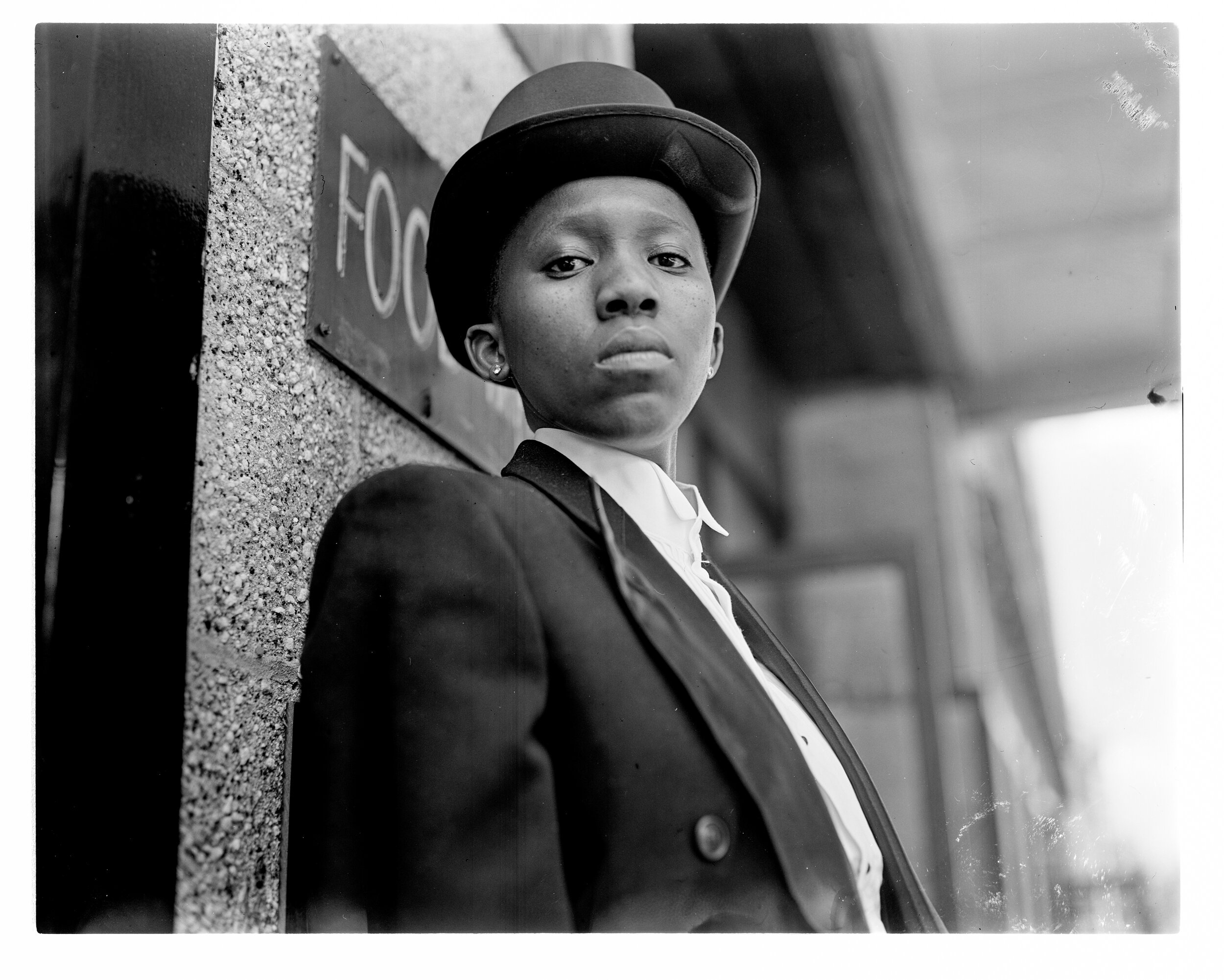

Felicita “Felli” Maynard is a genderqueer Afro-Latinx photographer based in Brooklyn who works against the silences of our archives and the violent history of photography to create images grounded in speculative history and consent. By foregrounding embodiment and ritual as important forms of memory and as models of archival activation, Felli brings together the past and present to assert that queer and trans Black people have a historical presence and will continue to exist.

I first encountered Felli’s work after reading Intergalactic Travels: poems from a fugitive alien (2020) by AfroIndigenous poet Alan Pelaez Lopez. In this collection of art and writings is a manifesto for Black and Indigenous artists, which opens with the lines quoted above, calling forth the most marginalized in the Americas. They argue that as people struggling against empire, we must take up the responsibility of remembering, that our ancestors “left us blueprints of how to resist, survive and thrive” in art, and that we need artists to win the revolution.

Echoing Pelaez Lopez’s sentiment that colonialism and empire have disrupted our memory, Felli takes on the responsibility of remembering those who have not been recorded in official archives and in our family albums. Felli’s black-and-white photographs document contemporary figures for a more expansive archive, validating the presence and entanglement of queer, trans, Black, and Latinx communities while also inviting us all to imagine and claim our unnamed ancestors.

Juan Omar (JO): You recently participated in The Now at Pen + Brush, can you tell me more about the exhibition and the work that you showed?

Felli (F): It was a group show with artists Hannah Layden, Rowan Renee & Beatrice Scaccia. All our work brought in aspects of what we felt are issues that are being talked about now, such as gender identity, body dysmorphia, anxiety, depression, ownership of your body physically and related to technology. The work I showed is part of a larger series called Ole Dandy. It looks into the lives of two fictional characters that I created, Jean Loren Feliz and Angelo Lwazi Owenzayo. They are both male impersonators that would have lived during the early 1900s. I have always been interested in the whole idea of history, queer history, how there are a lot of gaps that just shouldn’t be there. And then from an Afro-Latinx perspective—my mom is Colombian and my dad is Panamanian. I don't know any of my queer ancestors related to my blood line and who that could have possibly been in my life. So me creating these characters is a way of me also looking into my own history, but also looking into this bigger history—of queer, trans, nonbinary individuals.

I just started making this work. I was really influenced by When Brooklyn Was Queer (2019), by Hugh Ryan. In the book, I learned about Florence Hines who was a drag king during the 1890s, a Black drag king.

JO: During one of our email conversations, you mentioned that The Watermelon Woman (1996) by Cheryl Dunye was really influential for your work. I saw the film recently, and this one quote from the ending credits where Dunye says, “Sometimes you have to create your own history,” seemed particularly resonant with Ole Dandy. Can you talk more about this influence and about the role of speculative history in your work?

F: So I knew about The Watermelon Woman by Cheryl Dunye, but didn’t know about it. I kind of stumbled upon the movie while I was working as a gallery assistant at the Whitney Museum. They had a retrospective of Zoe Leonard's work, she was the photographer who worked with Cheryl to make the archival images for the movie. So I'm in the galleries. I'm looking at this work and I'm just like, “who are these queers?” These are like lesbians in the 1930s, and the main focus is this Black woman. Representation, representation! I don't remember if the exhibition said that the photo series was from The Watermelon Woman, but looking more into the work, I found out that it was related to this movie and then saw the movie and was just like, “this is really awesome.” I thought to myself, “how did I not know about this movie for so long?”

I'm supposed to be giving light to the fact that my ancestors existed. Giving light to the fact that there have always been fluid beings. The fact that colonialism has come in and messed up everything and basically made it seem that us Black queer people are not supposed to be here. We're magical people, we always have been, and we've been connected to things spiritually and magically. Re-finding The Watermelon Woman was just part of the whole thing to solidify that, like, “look, you're doing the right thing. You're on the right path. Keep doing the work.”

I'm doing a mentorship program with Queer | Art, an organization that helps with the advancement of queer artists. My mentor is photographer Lola Flash, who is dope and has been doing the work for so long. The first time I went to their house for our first meeting, there was a portrait of Cheryl right there. Things keep letting me know that I'm on the right path.

JO: That's really amazing! Can you talk more about this dynamic of being driven by the ancestors to uncover and create the stories that are hidden or missing in the archive?

F: Literally we all have a piece of the archive, like I tell people all the time, “you have your own archive. Your photo albums. Go back to those, those are your archive.” Those are literally parts of your family, pieces of things, moments in time that you can't fully understand but feel somewhat… feel very much connected to. I start off with that. Thinking about the queer archive and knowing how it hasn't been documented the way it needed to be or saved in the way it should have been, either for the fact of lack of understanding, erasure by family, or just someone seeking total privacy. When looking through the public archive I keep thinking about this thing of not wanting to “out” anybody. And even though the archive is important, going back into archives is very tricky because I don’t want to tell a story that doesn't want to be told. That's why for Ole Dandy, even though Florence Hines influenced most of the work, I didn't want to tell the story of Florence. I wanted to tell the story of someone who could have been like Florence, could have lived at the same time as Florence, but I'm not putting any words in anyone's mouth. Sometimes a person or thing you find in the archive was never meant to be brought back out.

The archive is a beautiful place, but it can be a dark and lonely place as well. A lot of the work that I'm trying to do, too, is just to make a more public archive—my characters have given consent to have their archive be out there, to basically educate people. I'm constantly thinking about how to integrate everything in a way that makes sense but also creates a safe space.

JO: I really appreciate you talking about the dynamics of the archive and the politics and potential issues of doing these kinds of creative interventions. When I first learned about your photography, I was thinking a lot about Carlos Motta's 2015 film Deseos, which features a fictional conversation between two queer women from the 1800s; one from Colombia and one from the Ottoman Empire. The character from Colombia, Martina, is based on legal documents of an intersex woman tried at the Spanish colonial court for having an “unnatural” body. Her story only exists because of this documentation that came from a legal system that criminalized non-normative bodies and “deviant” desires. I'm also thinking now about William Dorsey Swann, the first American—not just Black American, first American—to lead a queer resistance group, in the 1880s, and also the first person to dub himself a drag queen. And we only know of him because of his arrest documents in the legal archive.

F: And in tabloids. I'm thinking about how they would have had the conversation about people at that time, and it's not always, like, the most positive.

JO: Yeah, exactly. Using these documents to uncover forgotten or silenced narratives also has the potential of bringing traumas back to life. Your practice, however, circumvents that by creating these new images that look historical. Can you talk more about your choice of medium?

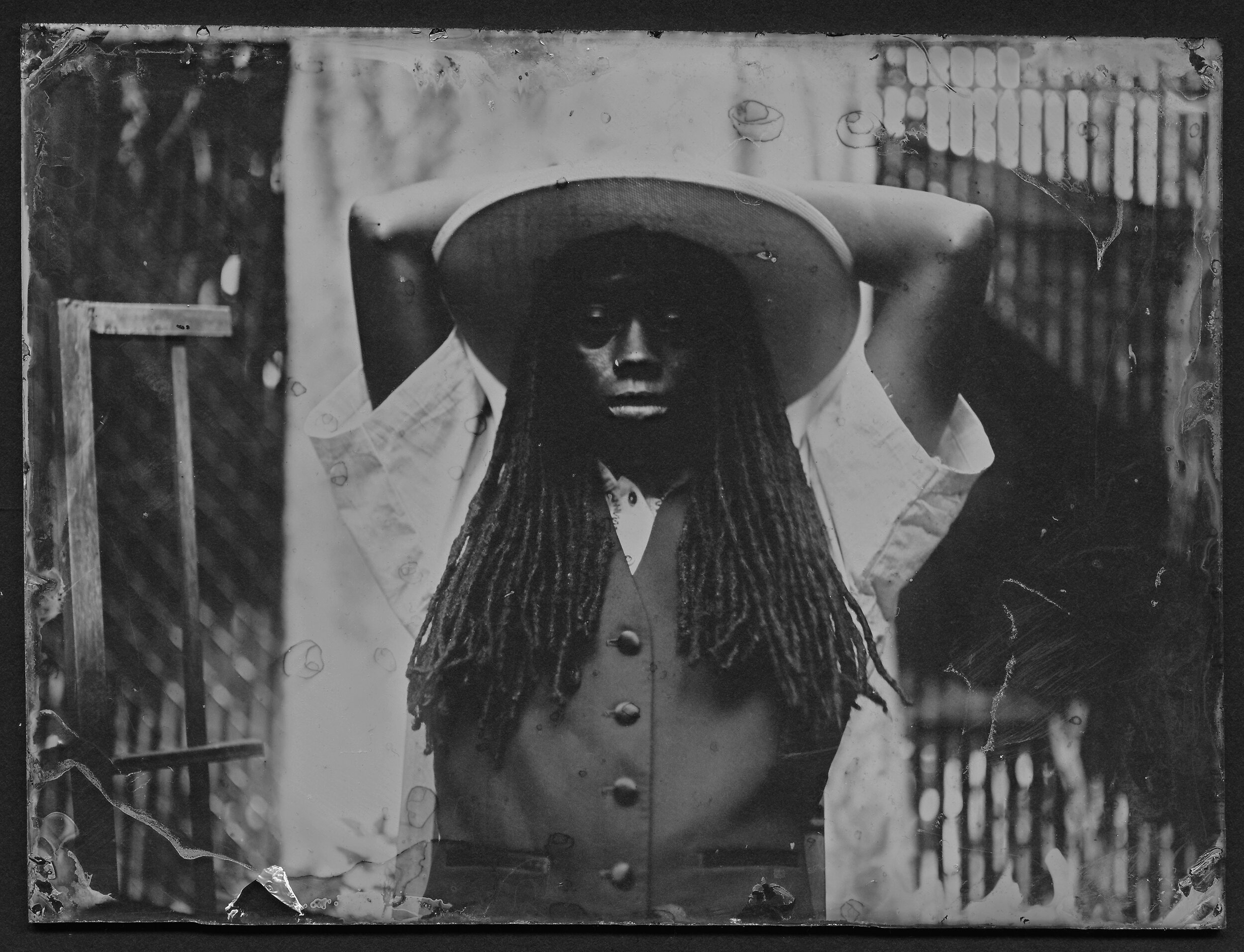

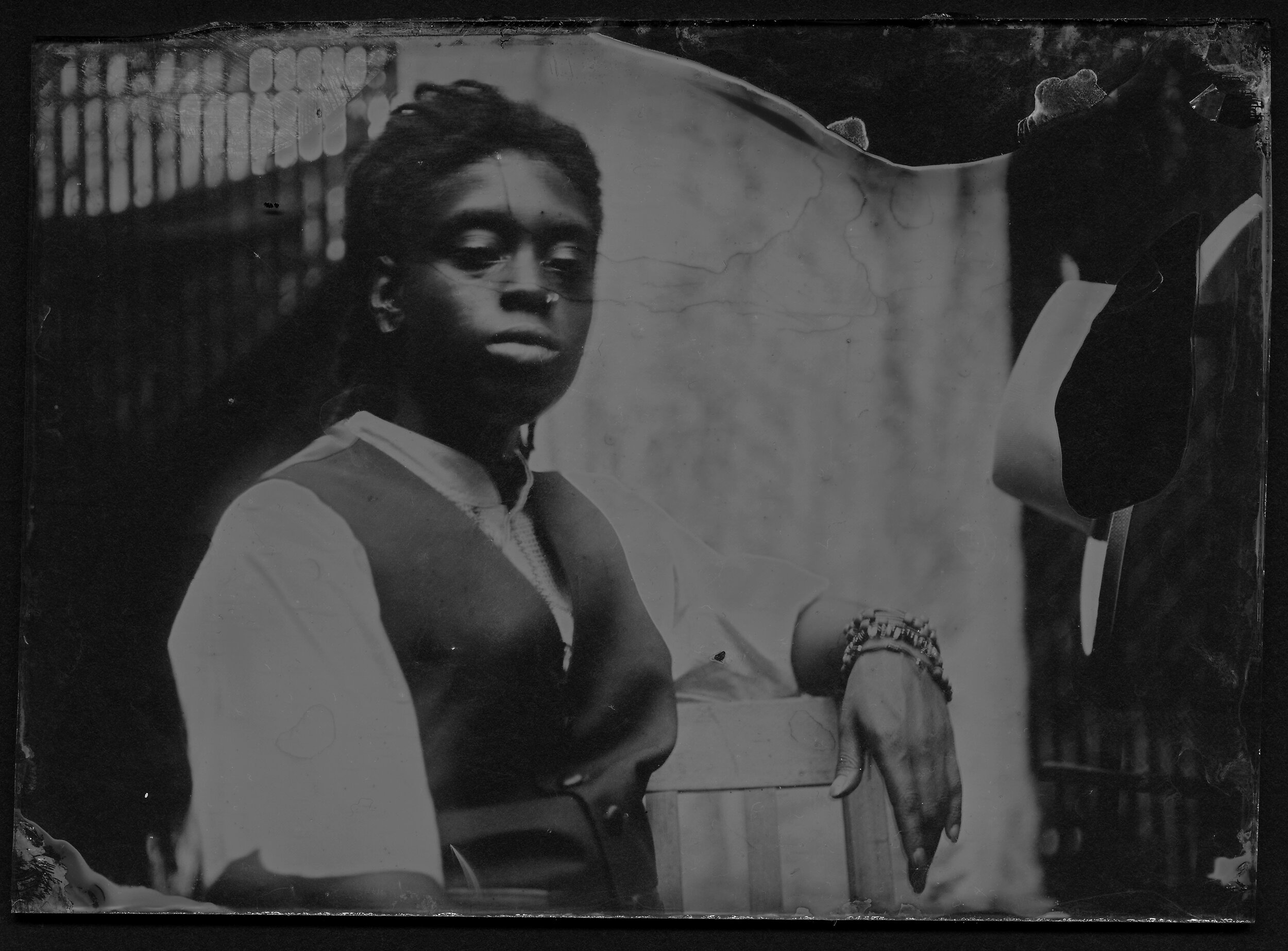

F: I became really interested in wet plate photography for two reasons. One reason is the history of wet plate photography. I'm shooting tintypes and ambrotypes, but daguerreotypes were the previous form, kind of like the grandfather of everything. The first daguerreotypes that I saw were the slave classification daguerreotypes by Louis Agassiz from the 1850s. These images are really gruesome, just non-consensual images used as a way to show that Africans and African-Americans were less than. I thought to myself, “what if I learned this process and then made new images that kind of cancel out these old, messed up representations of Black bodies?”

Photography was created at the same time that Europeans were colonizing Africa, so it was not only used to document atrocities but also implemented as a power tool. European photographers often did not ask the African people they photographed for consent, and they also staged many of the photographs to support the colonial project. Now we have these ethnographic images that are messed up. So what if I made a new set and found a way to still cancel out all this BS?

The second reason is that wet plate allows me to be the creator of all my materials, which I find is very important for my work. I want my hand in as much of the process as I can. With this process, I'm mixing my own chemicals. I'm collecting my own glass, so I'm trying to also do it in a way that's sustainable.

JO: We talked about ritual as another form of archive in an earlier conversation. How does this come up in your practice, especially in relation to what you just said about your presence in and ownership of the creative process?

F: Well, for me, I feel like every time I, especially with wet plate, do this whole process with someone, it's like an energy exchange between me and the person. We both are in ritual together because we have to work in unison in order to make this thing work. From start to finish, shooting one plate can take anywhere between 30 minutes to an hour, and that's just one plate. I want the subjects that I'm photographing to represent themselves how they want to be represented, and it's not about what I want you to do. It's what you want to do and how you feel to do it. And I don't want to capture your soul, but I want your soul to shine through the image. And in that sense, every time I do the process, because it's so intensive and it has so many parts to it, it becomes a ritual for me as well.

JO: In your Ole Dandy series, you photograph yourself as embodying one of your characters. I'm thinking about embodiment as a way to connect with the ancestors, to remember history—of being in history and bringing the past to the present. What is it like to photograph your own body?

F: It's so hard. It's such a process. Sometimes to take a self-portrait, it takes me all day. I'm also a semi-perfectionist when it comes to this work because it's very important to me. I want it to be as authentic as I can make it. In the Ole Dandy series, my character is Jean Loren Feliz. They are from New Orleans and their father is from Panama, and their mother is from New Orleans. Their father came to the United States basically looking for gold during the gold rush, and ended up moving to New Orleans. When I think about Jean, when I embody Jean, I think about people like Gladys Bentley. I think about people like Stormé DeLarverie, Florence Hines, and Mabel Hampton—she helped start the Herstory Archives in Park Slope. I try to embody these people but also do it in a way that—it's so many pieces. It's like so many pieces that I'm bringing together.

And even sometimes when I take the photographs and I look at them later, I don't see myself in them. I see someone else. I see Jean—I really do see Jean at times. And yeah, even when I'm performing Jean, too, I bring aspects of my grandfather and aspects of my uncles and make this character a very well-rounded person, not only based off of my experiences but also based off of the experiences of these inspirational individuals.

JO: Your images connect people from the past, present, and future, so I’m wondering if you can talk more about your conception of time.

F: Afrofuturism plays a big part in all of this just for the fact that with my work, I'm trying to have it be like layers of past, present, and future. There is no specific time for all this. This could even be happening right now in another time dimension. That's why it feels so right and so strong. Time is like layers. Time is not so static as we think it to be. So maybe even by doing this work, this ripple effect will go into the past somehow, and I know it's definitely going to go into the future.

We need to continue doing this work because there has to be more equal representation in just how people see our community and also dismantling a lot of issues.

JO: Yes, definitely. I’m wondering if you can talk more about representation and community and your relationship to Latinidad. Black people live everywhere in the Americas because of slavery and migration. But the prevalence of anti-Blackness and white supremacy throughout the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean erases this historical presence.

F: Blackness exists everywhere. It's a part of slavery. It's a part of colonialism. Black people are everywhere. They might be a very small minority where they are at, but they're there. So it's just like the Latinx community generally—Latinx people are everywhere, and part of it is from having to leave your home country to find a “better life.” And in a way, yes, it is a better life, but in other ways you inherit a whole bunch of things related to, ultimately the big problem, colonialism. And until we find a way to dismantle all that or really own up to the fact that that is one of the… that's the elephant in the room, there's just going to continue to be problems. That's just what it is.

JO: I’m a second-generation immigrant, so I think a lot about this sense of dislocation that I feel because of my proximity to the experience of migration. I remember you spoke about your experience as a second-generation immigrant in your interview for the New York City Trans Oral History Project. How does this experience inform your thinking about the queer ancestors in your immediate family?

F: That's once again another elephant in the room, and that's why I live my life so loudly because I want the next generation or whoever to have someone to look to. I've always been seeking some type of LGBTQ elderly community to be there for me, and that's why doing this mentorship program with Lola has been so important in my life and just so awesome. They're like the queer parent that I never had. It's kind of awesome. I think people don't realize, especially for us queers, the relationship that we have with home is already complicated. And then when you also add issues of immigration and issues of trying to find belonging, it's literally like just trying to belong on steroids because you're trying to belong at home, you're trying to belong within the LGBTQ community. You're trying to just belong in so many ways.

JO: That is so powerful. Lola Flash has a series where they’ve been documenting LGBTQ elders. Working under their mentorship, you've been in close proximity to these projects that are thinking about the people that are alive now who we can claim and celebrate as ancestors. I’d love to hear more about your relationship with Lola.

F: It's awesome. It's been such an awesome, awesome experience. And it's funny because—it once again shows me all the pieces are coming together. Before we met, me and Lola were in a show at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. I modeled for the Pur·suit deck, photographed by Naima Green. Lola also modeled for that. We're in a lot of things together, and it has been validating for my own work but also just shows me we were supposed to meet. Even if we didn't meet through Queer | Art, we were going to meet anyway because their name kept popping up. Before we met in person, I went to their big retrospective at Pen + Brush gallery. Amazingly enough a few years later I got to show work in the same space. I feel very blessed and very grateful to the universe, my ancestors, everyone in my community.

JO: What other projects are you working on?

F: I'm very interested in showing equal representation of people like me. I've just started doing a series of self-documentation, self-portraits, titled Studies on a Fluid Body. I'm coming more into myself and understanding who I am and also showing a lot of people that transness and gender nonbinary-ness and all that comes in many shapes and sizes. It's fluid. There's no one way that you have to look in order to be trans or to be whatever. If that's part of you, that's part of you. And through this work, I'm doing self-portraits. I'm writing journal entries. I'm also coupling it up with family photographs and things like that. Doing this deep dig to free myself but also hopefully free someone else in the process.

JO: Who are the artists that inspire you?

F: I’m really inspired by the work of Lola Flash, Texas Isaiah, Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Naima Green, Khadija Saye, Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Adama Delphine Fawundu, Dario Calmese and so many more.

Right now I'm in an awesome show Por Los Ojos de Mi Gente with Alanna Fields, Alexis-Ruiseco Lombera, Antonio Pulgarin, Derick Whitson and Golden at the Baxter Street Camera Club of New York, curated by Alanna Fields and Antonio Pulgarin. All of the work in the show is based on this search for queer community, whether it be within ourselves or through finding others like ourselves.

Zanele Muholi also has been an inspiration. And Renee Cox.

JO: What is on the horizon for you? What are you excited about that’s coming next?

F: I want to go to grad school. I think that's my next step. I think I'm at a bright point in my life and career to be thinking about that because my ultimate goal is to teach. I want to share this knowledge of wet plate to more Black photographers, to more queer Black photographers who might not have the access to learn this. Even for me —I had to crowdfund to learn how to do this, and even with that I had to be persistent and say that this is something that I wanted to do because the world of wet plate is very much a white male world. I want to uncover the histories of the Black women in my family and also at the same time work on creating a wet plate photography archive in Colombia of Black people there because I believe that they deserve, also, more representation. Colombia is very messed up when it comes to affairs related to Afro-Colombians. And hopefully with my privilege of being from the U.S., I can go over there and help and inspire and educate.

JO: Thank you so much for your generosity, for sharing your thoughts, your experiences, and your work with us.

F: Thank you for having me, and thank you for also believing in me. By doing this, this is also just more inspiration and positive energy exchange so appreciate it.

Felicita “Felli” Maynard is a New York-based interdisciplinary artist, student, and educator. They received their BFA from Brooklyn College, with a concentration in film photography. As a 1st generation Afrolatinx-American, their work uses photography to investigate and explore identity, gender, history and the black body. They challenge and re-write history by means of their work. Maynard has shown work at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, Westchester Community College, Spectrum Gallery at MCLA college, Brooklyn Photoville and Pen + Brush Gallery in NYC. Felli lives and works in Brooklyn NY.

Juan Omar Rodriguez is a Curatorial Fellow at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. He is co-curator of the inaugural edition of the biennial exhibition series, SMFA at Tufts: Juried Student Exhibition, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Before joining the ICA/Boston, Juan Omar conducted research and designed public programs at the MFA Boston and at the Tufts University Art Galleries. He completed his M.A. in Art History and Museum Studies at Tufts University in 2019. Originally from Phoenix, AZ, Juan Omar now resides in Cambridge, MA.