Pepe Flores is en la casa

Pepe Flores is a swirling ball of energy, usually dressed in a guayabera, bowtie, and some variation of fedora or Yoruban fila on his head, always looking to manifest some flash of the spirit to capture what’s left of the Latinx Lower East Side, or Loisaida. Most often you’ll run into him prowling along Avenue C, near his new gallery-gathering space, La Sala de Pepe, but very likely at a random show at Hostos Center, El Museo, or Lehman Center for the Performing Arts. Just last October at Jazz at Lincoln Center, as I was grooving on a live performance of “La Creación,” Chucho Valdés’s Santería inspired four-movement suite, I sat stunned in my orchestra seat to see Pepe emerging from the balcony to spin a dance partner down the aisles as the show climaxed.

As he came past me, I shouted hey over the pulsing polyrhythms and he gave me that big smile of his and went off on his merry way, engaging and disrupting the audience that was still not standing, wondering whether he was part of the show. Pepe was bringing back the feel and presence of Latin dance ballrooms long gone, the Corso on 86th, Casino 14 near Union Square, by just being his subversively signifying self. It’s no different from what La Sala de Pepe is trying to accomplish: while most of the East Village/Lower East Side has morphed into a gentrified playground for wealthy suburbanites, the neighborhood’s ancestral Puerto Rican past still breaks through the cracks and crevices of these storied sidewalks.

Flores was born in Puerto Rico in 1951 and came to New York at age 19, quickly becoming part of the Nuyorican era of the 1970s. He immediately embraced working in daycare education and community activism, managing to rent an apartment on 3rd Street for $75 a month through a community program called Adopt-a-Building. It was a time when Puerto Ricans were a majority constituency of the neighborhood, and a local poet named Bimbo Rivas coined the name for it, Loisaida, which fused the name of Puerto Rico’s main Afro-Puerto Rican municipality, Loiza, with the English pronunciation of “Lower East Side.”

Many of the central narratives of the Nuyorican Aesthetic were formed here, closely tied to the development of community institutions like the Nuyorican Poets Café, founded by Miguel Algarín and Miguel Piñero, and the New Rican Village, a music- and theater-oriented space run by Eddie Figueroa. I first met Pepe during his many visits to the 90s revival version of the Nuyorican Café, where he dressed in pretty much the same urban jíbaro outfit that he does today, mingling with the folks at the back of the bar, where resided Pedro Pietri, lugging around his Reverend Pedro briefcase full of poems, and Steve Cannon haranguing poets to edit their stage patter and “read the damn poem.”

Despite the neighborhood’s current incarnation as nihilist hookah heterotopia, I often feel comforted walking its still somewhat starving naked hysterical streets because of the ghosts of Loisaida past that lurk subliminally on memory’s horizon. And there’s still tangible evidence that the demise of Nuyorican Loisaida is perhaps exaggerated—the Loisaida Center, run by Ale Epifanio, still provocative and redolent of a glorious rice and beans past; the Nuyorican Poets Café, still vibrant under the sway of current director Caridad de la Luz (La Bruja), even a new space like David Soto (Daso)’s Piragua Art Space.

Last March, Pepe and his long-time friend, Lyn Pentecost, founder and emeritus director of the Lower Eastside Girls Club, were able to secure a storefront space just below the apartment where Pepe was living to house La Sala de Pepe and Foto Espacio. When you walk into the space, the first thing that strikes you is the homey feel—it’s literally a sala, from your memory of salas past, sans the plastic slipcovers on the furniture.

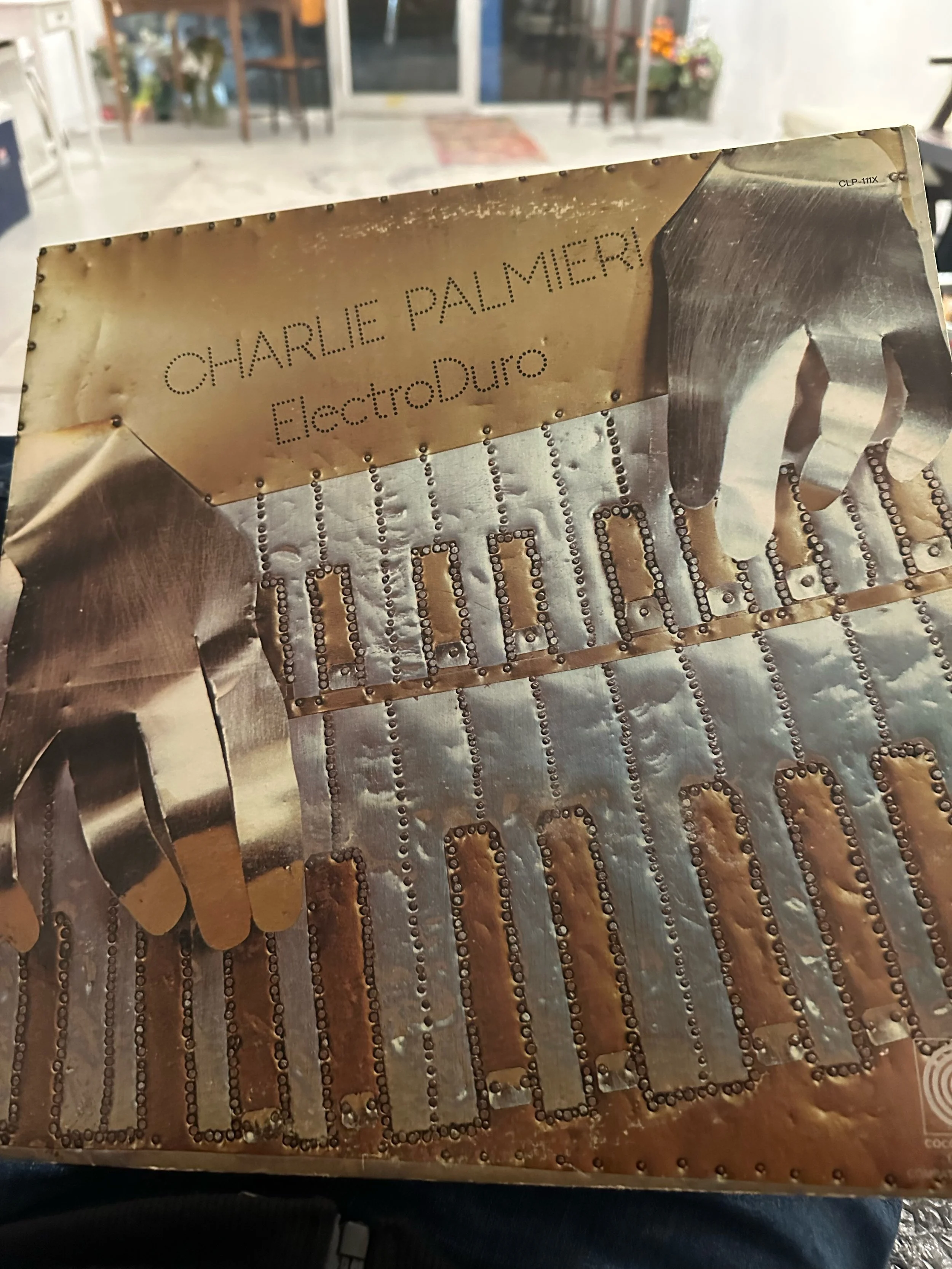

In its 10 months of existence, La Sala de Pepe has hosted or co-produced activities such as “Women in Bomba: Bomba and Beyond,” a Day of the Dead celebration featuring local Mexican musicians and a tribute to David Amram and Jack Kerouac, a “Hurricane María: 5 Years Later” event, “Jangueo y Justicia,” an event about police accountability in Puerto Rico by nonprofit Kilometro Cero, and on February 4th, the opening of an exhibition of works and album cover art by Charlie Rosario called “Dedicated to the Drum: 50 Years of Art and Design.” Pepe had been excited about this show when I had visited weeks earlier, showing me one of Santiago’s standout designs, the cover of Charlie Palmieri’s “Electro Duro,” which featured piano-playing hands carved from metal playing a keyboard of riveted gold and silver keys.

On permanent display in the Foto Espacio are a series of photos of classic salsa and Afro-Cuban albums: La Lupe, Machito, Tito Puente, Tito Rodríguez, even Eddie Palmieri’s “Sueño,” with a faintly visible sticker from the old Sounds record store on St. Marks Place. Pepe had not only been an arts activist, but was all the while swimming with the salsa sharks of New York, absorbing knowledge from mentors like legendary Latin music producer, historian, and collector René López. He witnessed the birth of a genre that was ultimately labeled salsa, even though he had grown up with it in Puerto Rico and his early years in New York, as a constellation of Afro-Cuban and Afro-Puerto Rican genres played by versatile bands with constantly morphing influences. He took me back to a recess behind the Foto Espacio to reveal a room housing his massive (6,000 or so) collection of vinyl, much of which he had moved from his apartment upstairs.

“Ninety-nine percent of this collection is what I collected in the years since I came to New York in 1971,” he said. “There were record shops in the 14th Street subway station, on Clinton and Delancey streets. Some of them were like holes in the wall. I mean, you come out with two bags of record shop, two bags, shopping bags on records for like $2.” The owners of those shops had no idea that the records would ultimately become collectors’ items, and they began calling Pepe to come over and pick them up.

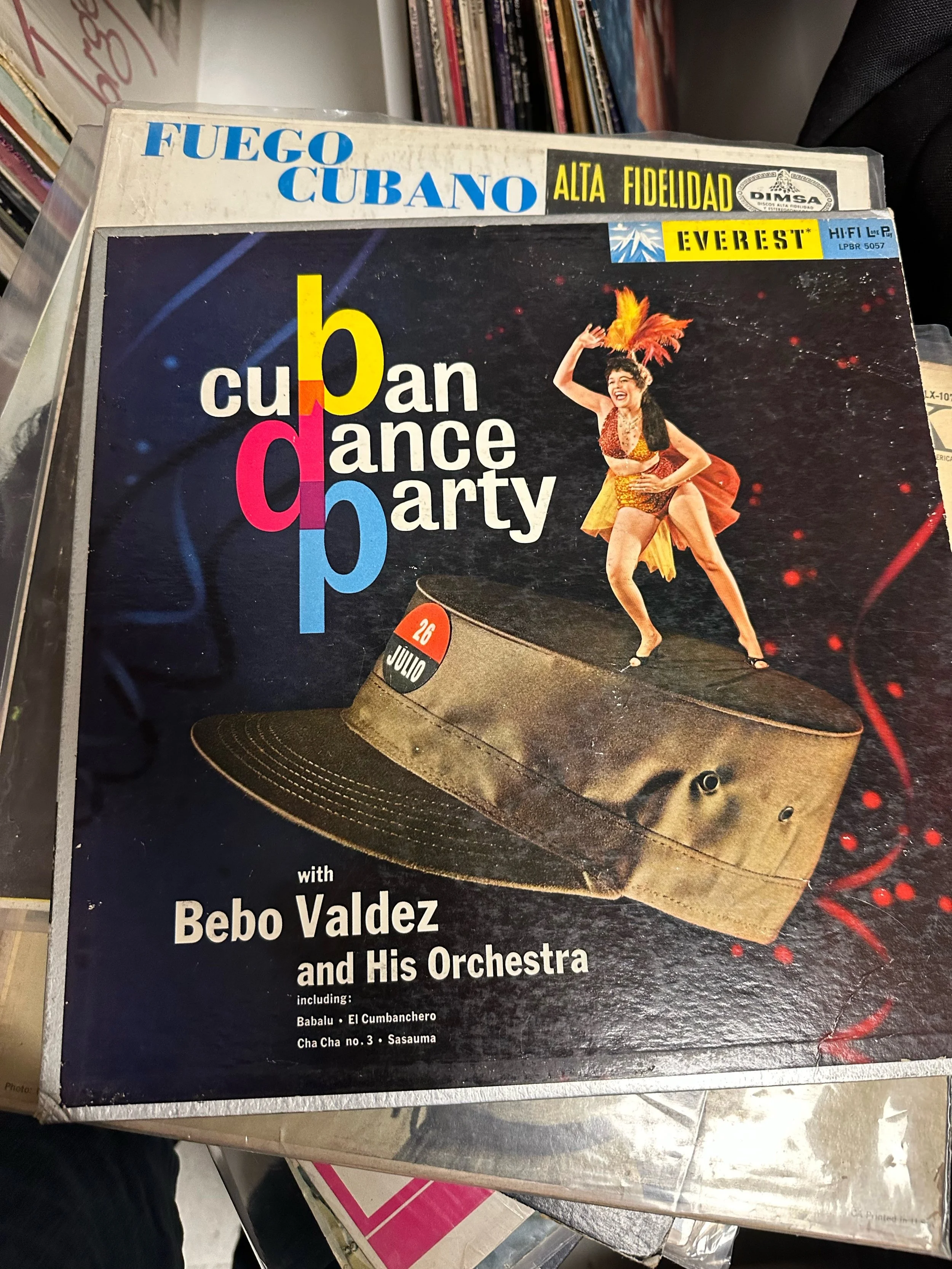

He begins to pull albums out of the stacks and show them to me, with several catching my attention. There was one from Cuban singer Luisa María Hernández, a/k/a La India del Oriente, with those liltingly familiar son guajira songs like “El Fiel Enamorado.” Then there’s the striking cover of a Bebo Valdéz and His Orchestra release “Cuban Dance Party” with a cover depicting what looks like a Hotel Tropicana dancer mamboing on top of a rust-brown military cap with a 26th of July logo, celebrating Castro’s attack on the Moncada barracks in Santiago, which despite failing ultimately became an important date in Cuban revolutionary history celebrated to this day. Gazing at the rare disc, I was temporarily suspended in the irony is that both Valdéz and Celia Cruz (“Guajiro, Llegó tu Día,” with Sonora Matancera) had made records celebrating Castro but soon became two of the revolution’s most famous musical exiles.

“Salsa music, which is a hybrid of Latin music, but I hate to use Latin music,” said Pepe as we moved to a series of Palmieri and Cal Tjader records. “It’s Cuban music and music from the Caribbean, Puerto Rico: there are elements of jibaro music in La Salsa. Yeah. You cannot just pinpoint one place. It's the songs of the children of the diaspora. Yeah. The ones that were born here in the forties and the fifties. They were affected by jazz and rhythm and blues.”

But did salsa have a moment of creation, or did it just flow out of the lives of diasporic subjects? “When I grew up in Puerto Rico, we never called it salsa,” said Pepe. “We just went to dance guaracha, bolero, merengue. I never called Cortijo and Maelo’s music salsa or Tommy Olivencia, or Roberto Roena and Apollo Sound. But there was a moment. That's the thing about how people commercialize things. They put a label in it, and nobody questions why we used the term salsa. All of a sudden one night you went to sleep and you played mambo, cha cha cha, and then the next day it’s called salsa.”

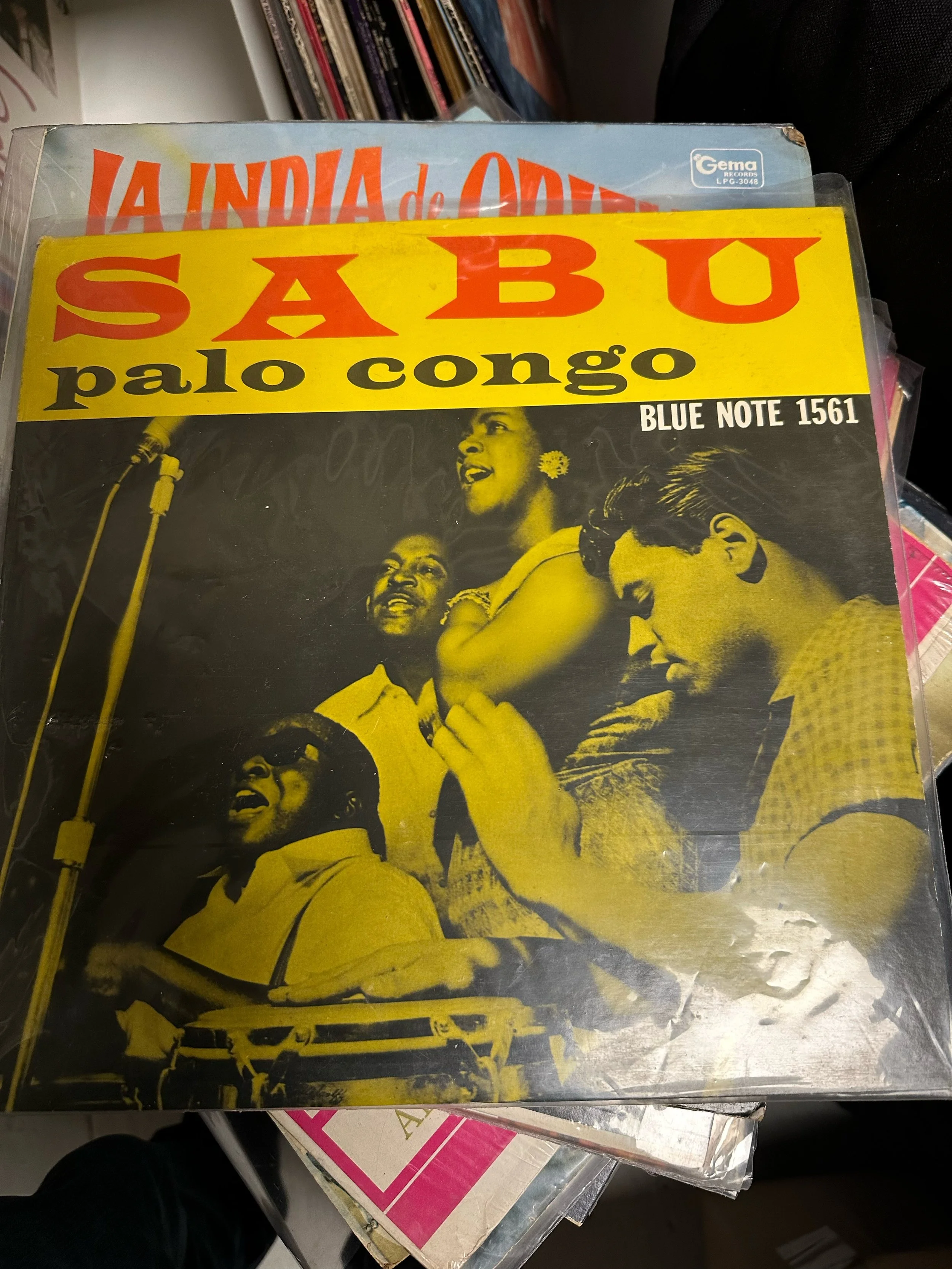

Then we came upon conguero Sabú Martínez’s 1957 classic “Palo Congo,” with Arsenio Rodríguez on the cover lifting his voice in song. While it’s moving enough to see this rare Rodríguez vinyl, as I dig deeper I realize that despite the Cuban classics “El Cumbanchero,” and rumba jams like “Bilumba-Palo Congo,” there’s a plena track, “Choferito-Plena,” and that Martínez is actually a Puerto Rican from Spanish Harlem and had an incredible career that saw him replace Cuban legend Chano Pozo in Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra. When the 1970s came around, Martinez was making electro-funk records like “Burned Sugar” and “Afro-Temple,” under-recognized echoes of post-Miles Davis fusion.

The power of Pepe Flores’s record collection is its simple reality as an archive of movement, migration, and memory. Acting as an organic curator of the cultural moments that he lived through, Pepe was already creating a new series of stories and connections in whomever comes in contact with it. Still, he’s careful about taking his ego out of it, always praising the musician, collector, and dancer community he came out of. “I would say René López is the biggest influence on this collection,” he said, with reverence. “Jerry and Andy [González] also influenced me, and Harry Sepulveda. But Rene was, René was the godfather of all of us. He taught me that you have to spread this music among people, you can’t be selfish.”

For Pepe Flores, it’s easy to say his casa es su casa, because, at least in La Sala de Pepe, it literally is your casa. Thousands of painstakingly cared-for vinyl awaits you to drop that needle onto the record and create analog sparks of life. Photographic records of culture and tradition reawaken the smells of pernil cooked by the descendants of Casa Adela across the street. Rising like Mikey Piñero’s ashes once scattered here, the ancestors never stop coming back to life.

Ed Morales is an author and journalist who has written for The Nation, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, and CNN Opinions. He was staff writer at The Village Voice and columnist at Newsday. He is the author of Fantasy Island: Colonialism, Exploitation, and the Betrayal of Puerto Rico (Bold Type Books), Latinx: The New Force in Politics and Culture (Verso Books 2018). Morales is a lecturer at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race and a 2022-23 Mellon Fellow at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies.