NEGRO/A/X: Visibilizing Our Aesthetics in Puerto Rico’s Corredor Afro

Marta Moreno Vega’s new project is hopeful. El Corredor Afro buds and flourishes in the middle of Piñones, Loíza as an alternative space for exploring Afro-Boricua aesthetics in the too-long colonized realm of visual arts and visual representation on the island. It also represents an/other path for developing race consciousness visual arts in Puerto Rico and its afro-global connections. Twenty-five years after Edwin Velázquez’s pioneering exhibition “Paréntesis: ocho artistas negros contemporáneos” (1996), there is a space that does not require “clear unbiased justification” for the showing of art pieces centered on the issue of race.

NEGRO/A/X is definitely a groundbreaking project presented in an alternative arts space and community based cultural center. It presents the work of 20 artists, all approaching “race” as the center of their artwork.

The exhibit opens with a piece by Celso González, a visual artist and curator of the exposition. His sculpture “Se acabó el juego” depicts a black boy, sitting on the floor as if resting after an intense basketball game. The sculpture is a montage developed through found materials—driftwood, cardboard, a broken baseball, plants. The materials selected by Celso González speak for themselves; the driftwood references Piñones’ beaches and its still untouched coast. In its sands one can find driftwood transported by high tides, hurricanes, and storms from unknown places. The resting boy can metaphorically tell stories of many “games” that have kept him running throughout the centuries of African exportation, slavery, mass incarceration, and exploitation. The “game” from which he is resting reminds the viewer about how sports have been the only comforting activity for many young black boys—in school, in the community, in jails and in one of the few industries—“the sports entertainment industry”—that have offered economic gain for afro-descendants.

“Dirt and Pain” by Papo Colo establishes a dialogue with “Se acabó el Juego.” This interdisciplinary performance and visual artwork presents a high contrast painting that uses natural pigments in order to represent two silhouettes of enslaved people as ghosts without faces in the lower half of an ochre stained canvas texturized and intervened with dirt. Devoid of facial expressions, their “facial erasure” reflects on the politics of dehumanization through enslavement. The use of traditional painting techniques, intervened and with the experimental use of dirt as texture and pigment also signifies, adds metaphorical meaning to Papo Colo’s piece. Our ancestral lands and the earth itself tell the story of enslavement and the pain of its victims.

In front of “Dirt and Pain,” Daniel Lind-Ramos’ “Victoria en cangrejos” tells the other side of slavery in Puerto Rico during colonial times. The black and white drawing on canvas, uses the Afro-Boricua symbols of crabs, vejigantes, and flying macheteros to retell the stories of community resistance and victory. In the upper center of the drawing on canvas stands a Yoruba sculpture of Xangó—God of War and Justice. On the right, the community of Cangrejos and Loiza confronts the fortified walls of Colonial San Juan. In the center, the battle takes place on land and sea. Daniel Lind-Ramos makes reference to the 1797 victory of the Milicias Pardas y Mulatas over the Invincible English Armada, a victory that remains unrecognized for the Afro-Boricua community. Vejigantes and Cangrejeros continue the mythical battle to survive amidst the polarized forces between community and colonized “settlements.”

The archetype of the vejigante is very present in this magnificent exhibition. David Sepúlveda’s (a.k.a. Don Rimx) piece, “La Tradición,” plays with the trope. His painting uses wood and acrylic to center on a vejigante that exposes his human face under the mask. The piece is influenced by graffiti in its use of color, graphic design, and intricate depiction of texture. It is interesting how the “old” dialogues with the ”new” languages of Afro-boricua visual arts in Sepúlveda’s “La Tradición.” The result is an Afro-Futurist piece that reminds us of a reimagined “escudo nacional” or national emblem, a maroon shield of arms for the Afro-Boricua community.

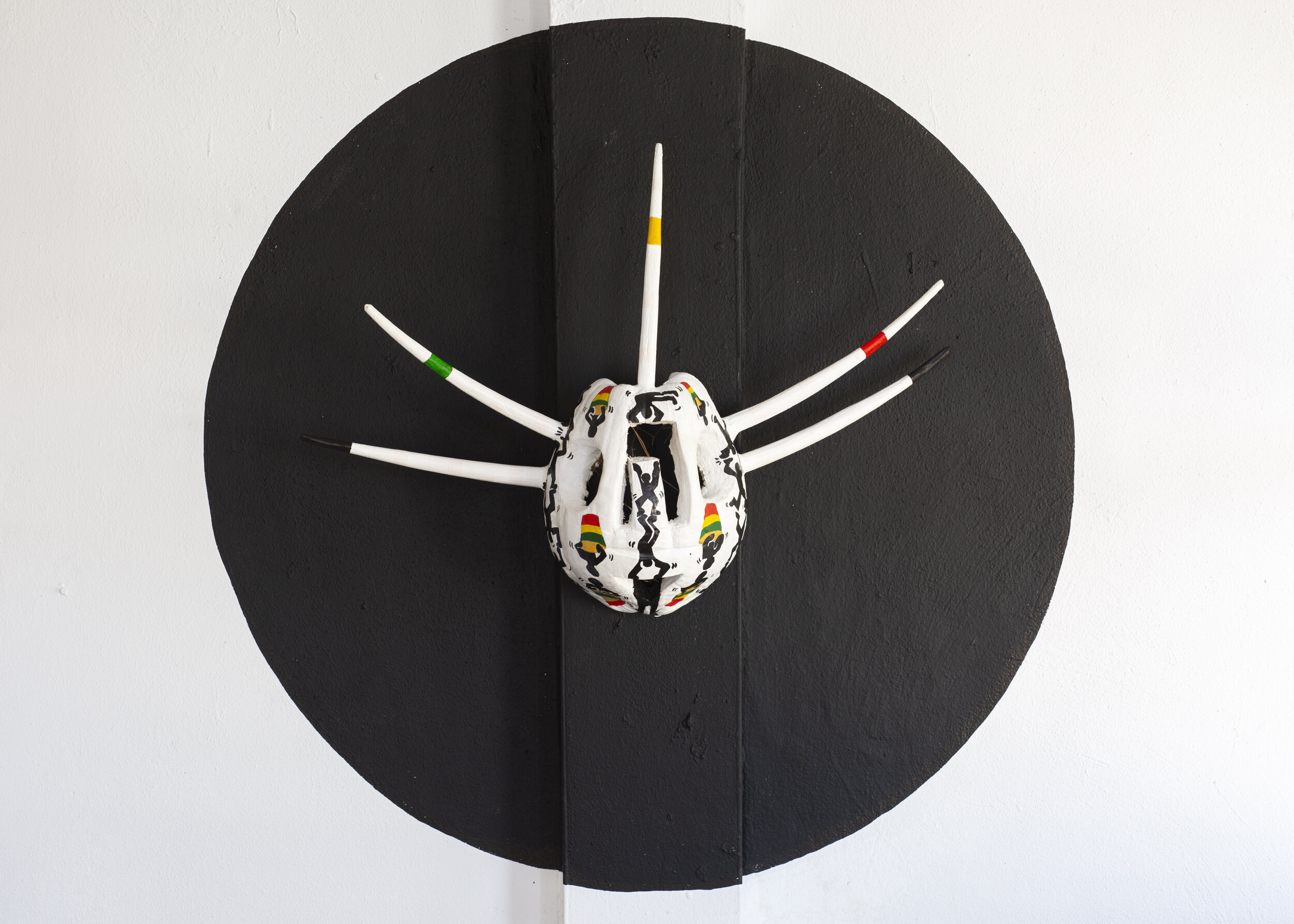

Jean Oyola’s “El Batey (Homenaje a Keith Haring)” also redefines the archetype of the vejigante. His piece pays an Afro-Boricua homage to Keith Haring. Oyola remixes Keith Haring's visual language on an Afro-Boricua “bass”, creating a high contrast piece that combines color, tradition and pop-art and the “cuir” visual arts tradition as it is adopted and re-signified in Puerto Rico.

Nancy Melendez sculpture on ceramic and wood “Reverencia” takes on the traditional colonial depiction of Black women, giving it a contemporary twist. Melendez gives a leading and central focus to the marginal depictions of African and Afro-descendant women in colonial paintings and embellishes while treating them with respect. The addition of natural elements (flowers, fern leaves stenciled on the nude torso) gives new meaning to the kneeling, servile pose imposed on the Black subject. Through Nancy Melendez’s hands, “Reverencia” communicates reverence to nature:human, spiritual, and earthly. In this way, “Reverencia” presents another archetype native to the Afro-Boricua aesthetic—the recognition that we are deeply connected to our natural surroundings in spirit and struggle.

With “Petrona, la rebelde,” Roxana Jordán creates an altar to pay homage to the cultural and lived resistance of racialized women. Her installation incorporates more Afro-Boricua archetypes, i.e. the Spiritist “bóveda,” calabash for burning aromatic herbs for “sahumerios,” candles, chains and spiritual “baños.” The importance of Afro-Boricua spiritual practices is the central theme of Roxana Jordan’s piece. A bird sits on the Black woman figure sculpted in clay, as if natural spirits are entering into deep communion and conversation with this powerful Black woman.

Samuel Lind’s “Osain, Espíritu del Bosque,” also makes reference to the Yoruba pantheon in his sculpture. He represents Osain, the God of Medicine, keeper of the healing powers that reside in herbs and plants. This beautiful bronze sculpture portrays the movement of ashé, the African concept that explains how “energy” travels and merges all living things and creates the web of life. Osain the healer is a branch, a man, as well as the buds of regeneration. His gaze is directed inward and outward at the same time. A third eye sprouts from his forehead, signaling wisdom and power that comes from within but that is shared with those who connect to him in their search for spiritual and material health.

The portrait “Ama de leche” by Damariz Cruz (Damalola) makes a visual commentary about the sustained servile condition of the Black woman. Damaris makes an assemblage using found materials: wood, old telephone directory pages, over which she paints a Black woman tending a white child. Afro-Caribbean women as caretakers of white children and elders is still one of the main sources of income for our community. Race, class, and gender intersect in this piece, especially in the title “Ama de leche,” which alludes to the long history of “employing” Black women as wet nurses. Art historian Marielba Torres raises attention to the existence of the first illustration of an enslaved woman in the history of Puerto Rican art. This illustration was produced by Luis Paret Alcázar in the 18th century. There is a strong resemblance between this illustration and Damariz Cruz’s painting, Both Black women carry a white child. Through her painting, Cruz invites the viewer to review the history of Black women representation and social positioning in our societies and to notice how little has changed over time.

“Negra Gallardía” by David Zayas portrays a rooster framed in a faux-rococo wood carving. The rooster on Zaya’s acrylic painting can be read as a very intentional tongue in cheek commentary about the erasure of blackness in the construction of Puerto Rican symbolic languages. David Zayas reminds us that among the “campesino” community, often referred to as “gallos,” there were many Afro-Boricuas. His decision to paint a “rooster” makes a clear reference to the whitewashed jíbaro patriarchal culture. But he puts it in technicolor. The rooster and the painter merge in the portrait. Thus, this piece can also be read as an anthropomorphized animalized self-portrait of the artist. This reading also conveys another layered meaning: that the very act of being an Afro-Boricua painter is an act of “gallardía,” that is, an act of bravery and valor.

Deyaneira Lucero’s series of paintings and photography centers on the role of masks as artefacts through which the voices our “egunguns” in community and ancestry communicate with the living ones. Deyanira also dialogues with the vejigante as an Afro-Boricua archetype using the tradition of masks made with palm trees. Through her work, Deyaneira makes reference to the existence of marabuntas, diablos cojuelos and other masked “beings” in Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latinx cultures and the ways in which the masks represent a message of knowledge and truth that comes from our dead ones in their plight for justice and social balance.

Christian Gonzalez’s “Face-Off” explodes with color. This Afro-Boricua interdisciplinary artist born in San Diego but based in Puerto Rico, uses music and color to create this portrait. Again, we can read references to the vejigantes and the way in which ancestry—as understood in the Afro Boricua tradition—help develop a sense of “self.” The mask-face moves as if following a beat, a jazzed “improvisation” of forms, numbers and colors. The intentionally primitivist and expressionist painting uses the African mask tradition to portray the many faces that become our face, the many selves that inhabit our identity.

“Rulé de la luna” by Eddie Loíza and “Tite” by Lucindo Fidalgo make direct reference to the centrality of music and dance in the construction of Afro-Boricua culture, identity, and radical self-expression. “Rulé” is a type of “toque de bomba,” the Afro-Boricua musical genre par excellence. “Tite” is a portrait that honors legendary Catalino Curet Alonso, composer of Afro-Boricua anthems such as “Las caras lindas de mi gente negra,” sung by Ismael Rivera.

Zuania Minier’s “Pelo Crespo,” redefines “Black hair” as part of nature. Braids, moños, and rizos are compared to roots, leaves, and vines. “Pelo Crespo” is part of a larger piece developed by this Afro-Dominicanarriqueña visual artist entitled “Bien conocemos los moños de las niñas.” Hair texture is a sign of Afro-Boricua and Afro-Dominican identity, one that signals African descent amidst the various colorisms in our intertwined diasporic communities.

“Cuéntame de tu gente en la orilla” is an installation piece created by Lisa Soto, an Afro-Boricua who lives between Puerto Rico and Ghana, and grew up in New York and Spain. Her installation uses rope, sand, fishing lines, seashells, and birds nests to enmark a video interview with a fisherman in Loiza. The whole space of Corredor Afro transforms into one of our coastal towns, a place where migration meets survival, work meets añoranzas, and poverty unifies nature with the people that live from it.

Lisa Soto’s installation enters in dialogue with the Las Nietas de Nonó piece “A condición de la sala de estar.” Las Nietas de Nonó create an altar with found industrial artifacts, coconuts, ceramic elephants and iPhone charger cables. Caribbean kitsch meets industrialization and its air conditioned “leisure” that would keep us free from the sun. Las Nietas de Nono comment on how our “aesthetics” re-colonized modernization through the insistent presence of Caribbean nature—symbolized by the coconut and the re-signified symbol of the elephant as a token for strength and endurance as understood in Afro-Boricua spiritualist practices.

Finally, the exhibition closes with legendary Afro-Boricua artist Diogenes Ballester and his oil painting “Velad por nuestra patria.” Ballester is one of the most established Afro-Boricua artists in history, living between East Harlem and Ponce, Puerto Rico and receiving the 2007 Prize for the Best Contemporary Art Exhibition by the International Association of Artists. His portrait of a Black Woman with her head filled with cowrie shells portrays the timeless presence of African ancestry in the construction of Puerto Rico.

The variety of visual languages brought together in the NEGRO/A/X exhibition is a testimony to the fractality of Afro-Boricua art. Even though the uniting focus is singular—Afro-Boricua artistic expression—the manifestations are diverse, multiple, and rich. Documentary photography (as in “Negra” by José Pipo Reyes), sculpture, installations, paintings, drawings, masks, and multiracial dolls (“Mis adorables”) offer the many languages and art traditions the opportunity to “speak” through the hands of Afro-Boricua visual artists. The exploration continues, as more alternative spaces open on the island, offering the much needed spaces that have been consistently denied to Afro-Boricuas to present their art. If museums are one of the major tools for the colonization of the imagination, Corredor Afro is a much needed anti-colonial antidote. NEGRO/A/X is food for the soul and hope for our artists, who are at last treated with respect and offered a place to nurture their visual languages, and who, in turn, expand the languages of all African diasporas in the world of the Afro-possible.

To take a 3D virtual tour of the exhibition, visit: https://corredorafro.org/negro-a-x/

Mayra Santos-Febres is an award-winning novelist and poet born in Carolina, Puerto Rico in 1966. She studied literature at the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) and completed two postgraduate degrees at Cornell University. She has been a guest professor at several universities in Latin America and the United States. She is a professor of creative writing at the UPR-Río Piedras campus and a member of the International and Multicultural Institute at the UPR. To read more, click here.