In Conversation with Artists Marisol T. Martinez & C.J. Chueca

Latina artists often serve as interlocutors for one another, and we learned about these two artists, Marisol Martinez and C.J. Chueca, who forged a friendship after participating in XX at Latchkey Gallery, a group exhibition featuring Latina artists who engage with abstraction. Since then, they have remained close friends and occasional collaborators. In this conversation they discuss horizons and skylines, color theory and affect, and grief and solidarity among artists during the pandemic lockdown.

Marisol Martinez (MM): Because I'm a color-based artist and a color theorist, color is always going to be what attracts me. I am drawn to your “airplane windows” and the beautiful mural you made which reflected the view from your window at your home in Lima during the pandemic, both reflecting different views you encountered. How did that juxtaposition feel? One of the views is from a plane which shows your travels and the other is doing the opposite: it is a stationed view. Was your feeling of both “views” the same?

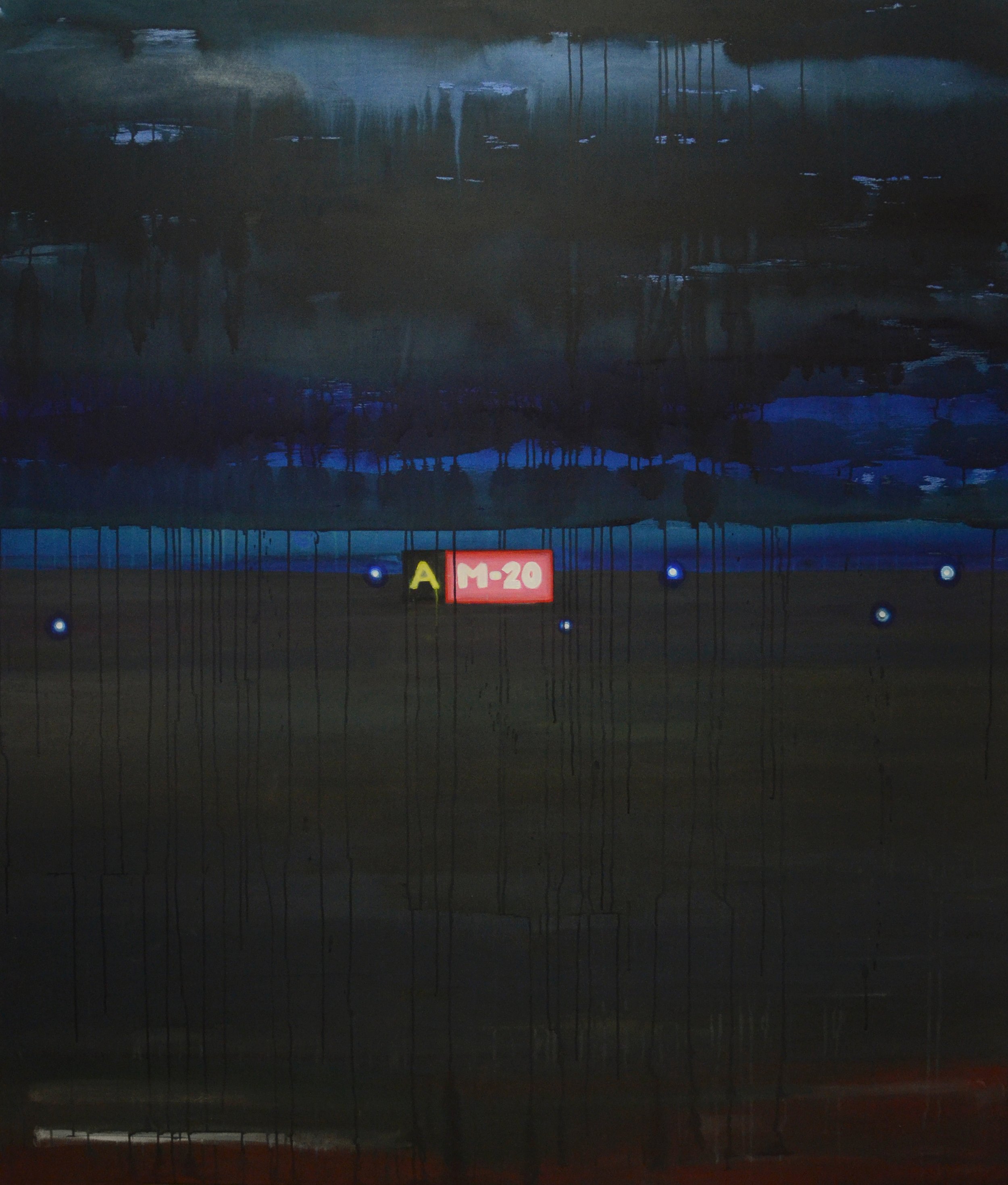

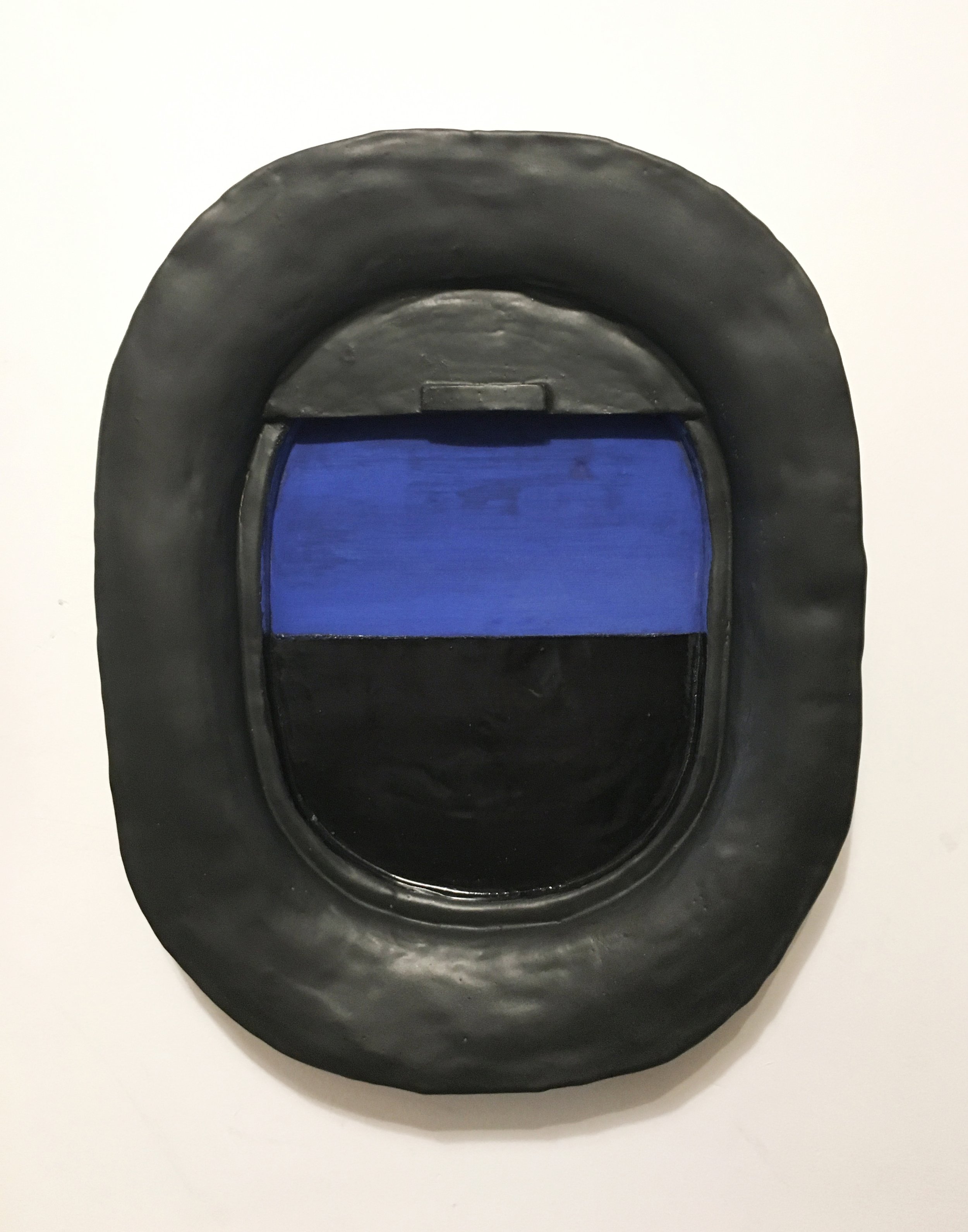

C.J. Chueca (CJC): I wanted to have a sense of the open space that the sky gives you regardless if you are moving or not. Because it is so large, it will always be around you. When you walk through them, the ceramic airplane windows talk about change. The title of the series is We are night and day and a few years ago I titled another group The fugitive days. Each window has this calm aspect of two colors forming a horizon, or sometimes they are almost a monochrome field. There is also the presence of the airplane window that itself calls to mind ideas of transport, immigration, transformation, change of moods, etc.

The mural at the show was a view I was seeing over and over from my static pandemic bedroom window. On some days that view was more yellow, and on another day more blue. Even when it was totally foggy, the same horizontal line remained, the same division was there.

The window is also a confrontation of us, humans in lockdown, immobilized looking at the grandiosity of life in front of us. This time, without being able to form part of it.

MM: How did you go about choosing the color palette for your windows?

CJC: I draw from real trips I’ve done. That’s why I title each window painting according to the seat I sat in: “31B”, “16C”, and so on. But instead of recreating what actually was the view from the window of that particular trip, I think I was more interested in the mood I was in, and then I chose how that mental state translates to a certain hour of the day. Let’s say: 5:30 am, dawn, or the sensation of waking up. That very bright light that you see when opening your eyes in the morning. From there, then I say, OK, this window will be all shades of white. If a particular trip was a sad trip, or if I felt sad leaving that city, then I play with other hours of the day. It is in my interest to put a few windows together because we pass from one state to the next all the time––physically, emotionally, legally, etc.

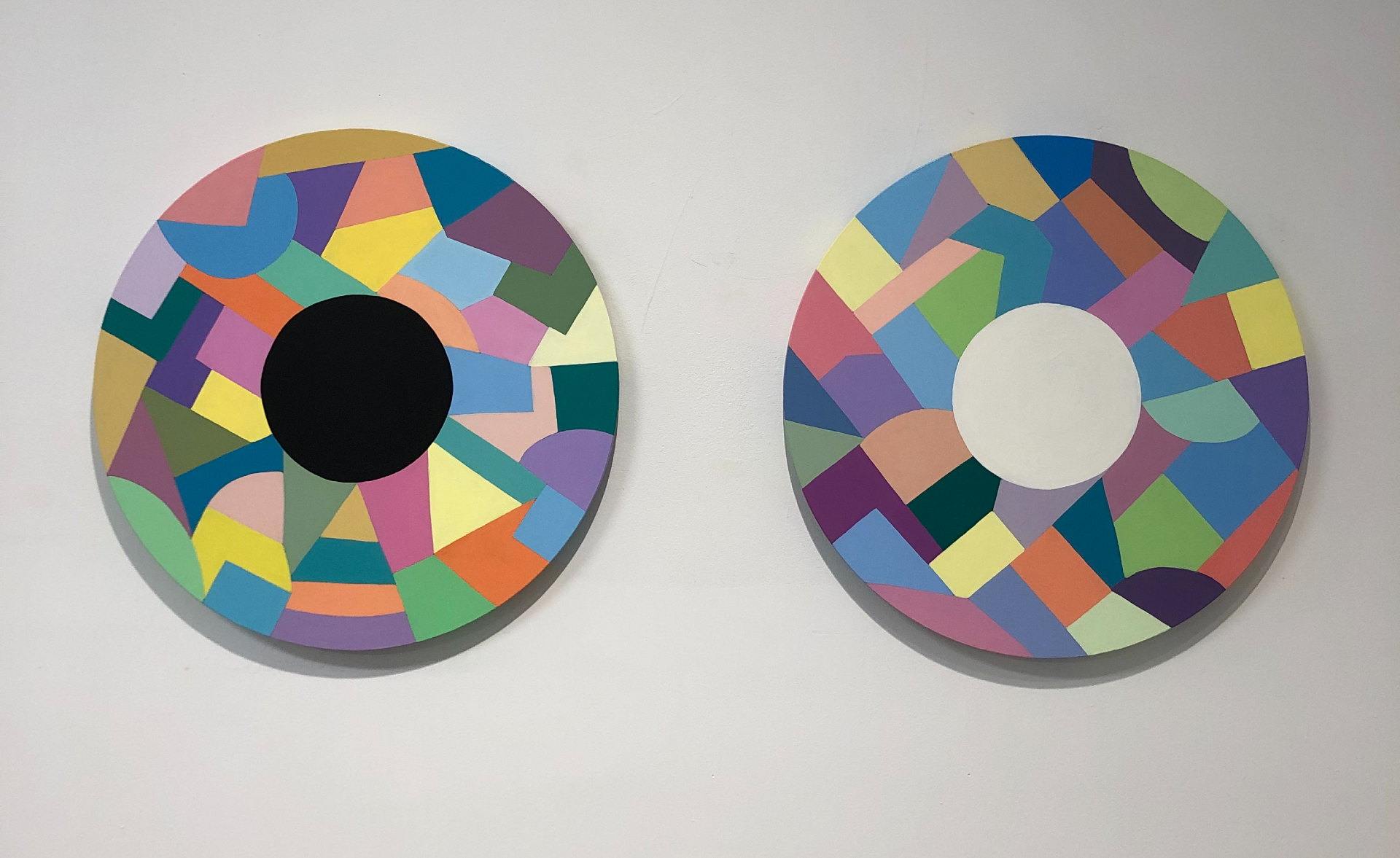

MM: That makes beautiful sense to me. I appreciate your ability to show your emotional state through color. I feel very connected to that. As an artist I see myself as a colorist in addition to many other things. What do you consider yourself? Do you put yourself and your work in categories or genres?

CJC: Because I navigate in different waters, I consider myself more like a music composer. I like to make exhibitions that have different media playing in unison. I work congregating gestures of an idea to form an experience. Mostly I work with materials that are either hard and breakable like ceramics, or I work with the sky and water that are intangible (almost the opposite). Ceramics are what I feel most connected to. There’s something about the fragility of ceramics but also the hardness and how it has been present in many different traditions from Western to Eastern culture, and also in many Indigenous cultures.

Most of the time I work with abstraction because for me it’s about the hardness, the sensuality, the loneliness, and the traces of certain materials and colors. And color is also about the absence of color, like sometimes I think in whites or blacks, and also in different tones. I do think that color is very charged.

What about you Marisol, do you think there is a category that you feel close to? You are yourself working primarily with abstraction…

MM: The category I feel personally connected to is “colorist” though most people know me as an abstract artist. I resonate with “colorist” because it is what drives me. I am super in touch with my emotions and the way I navigate the world as a human—the colors I choose reflect the mood and language I want to convey through the work. Without color my work has no words, no feeling, no expression. At times I can be anti-colorist—more minimal, playing with black and white which some argue are not colors, but that is work I have not shown much of to the outer world. I like the feeling of playing with intensity and softness.

CJC: I understand what you mean. But even when we use one tone of black in the entire piece, in my case, a wall for example, in your case, a large painting, even that one tone of black says a lot.

MM: Yes, I agree. The intensity of one color can smack you in the face, it can hit you harder than multiple colors which can be a distraction.

CJC: Sometimes I find abstract works to be more direct than figurative works for the public, in the first impression, in the sensorial first encounter. Is that first interaction with the work important to you?

MM: Yes! The sensory interaction with painting is what I am in love with. Not just in the actual work of making the painting but also in seeing other people’s sensorial reactions when they see it for the first time. The connection they make is purely related to themselves and their soul, removing me completely from the work. I enjoy watching people have a connection to themselves, carving their own narrative—that excites me! They give me perspective and personal stories I may have not seen or experienced otherwise. In essence, it's a form of storytelling without the actual story being obvious, like it can sometimes be through figurative painting.

CJC: There are qualities in both worlds of abstraction and figuration that engage with the spectator. But somehow I feel more related to the connections that are made through materiality, through color, and through shapes. You can be very political through abstraction, but that’s a long conversation.

It comes to mind how your family business these past two years has literally influenced the tone of your paintings. You run a funeral home…

MM: Yes, I grew up with my father and godfather, both owners of funeral homes. A few years ago, my father passed away and my brothers and I inherited the business, and to this day we manage it. That industry is very heavy and dark (literally and figuratively). It takes an emotional toll on you. During the onset of the pandemic, it was heartbreaking to hear people saying, “no one's taking us because they are at capacity,” or to have people calling from other states because they just couldn't get a funeral for their family member. These are the most heart-wrenching stories, and a lot of the cases that we had were families who were also immigrants or undocumented. It was an intense situation to deal with. You're trying to find ways to help families that don't have resources, and it was a level of stress that I've never experienced before. It got to the point where I was going to end up getting sick. Working on painting in my studio was about having a moment of not thinking about it. I don’t use any rulers, tapes, or tools in my work, it’s literally all freehand. For me, finding stillness, peace, and quiet was coming from working on the lines and the colors in the painting.

I know without a doubt my work in color comes from the need to color my world and my life. I was creating a world full of vibrancy, excitement, freedom, and joy all through the use of color. It makes me feel alive. My work has lots of layers in narrative and feeling but the overall tone is connectedness to whatever is happening to me, to you, our community, and the world. My intention is to invoke honest conversation, potential healing, and self-connectivity. I believe being raised around death my entire life has increased my ability to dig deep and reach for the uncomfortable. Abstraction is not comfortable for the most part and that's exactly why it is a natural fit for me.

CJC: These times have been very somber so I understand what you’re saying. I have seen colorful statements from artists these past few years. Myself too. It’s like survival mode.

MM: Survival mode is a perfect statement. I love the pure joy that comes from color. Within the past few years, we both created work that helped us get through very somber times. And in turn has helped people feel understood, seen, and loved.

CJC: I guess we were under so much pressure and an unknown future that creating parallel worlds––ones as uncertain, abstract, and indescifrable as our state of being––was a natural thing to do. During COVID, I started to make these paintings of landscapes that were darker, with a lot of dark droppings. I made a painting titled A.M. 2020. I think that my positivity went into a dark place. And I think it was good that I went to that dark place in my work, too. For some part of my life, my work was more political, and then it became more personal. And now I think that the personal becomes political somehow. I think that art did a lot for people that wanted to talk about issues happening now. Art has certainly helped as a connector. In this moment of confinement, the little bits of color, in real life, are a treasure. For me, to paint feels like an extension to one’s limited life.

MM: Cecilia, thank you for this statement, “To paint feels like an extension to one’s limited life.” You connected another dot for me. That is what art has the power to do: expansion.

CJC: Yes, and your friendship appeared while we were in the midst of grabbing rays of life, as an expansion we needed to continue. I think art was important during this time, as it fostered camaraderie between artists.

MM: I completely agree. Also, participating in the XX exhibition at Latchkey Gallery in 2021 with other women artists really helped bring me back to life and gave me a renewed sense of self. I felt so much joy being part of a show that highlighted incredibly talented women within an industry that is male-centric. Prior to that show, I wasn't really seeing a lot of other Latina abstract artists being shown in museums or galleries, other than very sparingly, like Carmen Herrera and Luchita Hurtado. Convening with artists in the XX show made me realize I'm not the only one out there. I was so overjoyed to be able to see other Latina women doing abstraction in their own way. We each had our own voice and our own distinct style. Meeting all these women was so exciting and everybody was so nice and supportive. I get choked up thinking about it. It was amazing.

CJC: It was a very nice time to collaborate on different levels. I think that a lot of ideas were exchanged, and we established some beautiful connections with the soul. That show XX was a beautiful time for us because all of the artists felt connected. I still keep in touch with the other women who were in the show and exchange messages.

MM: Speaking of women, your most recent solo exhibition was in Cusco, Peru in Fall 2021. Can you talk a bit about that?

CJC: Yes. The show is titled Micaela, the blood of all women. It is a break from my usual visual and conceptual rhythm to discuss a concern I have had since forever but was very present during the pandemic: the never-ending fight of women for liberation. Micaela Bastidas was a mixracial woman (from Indigenous and Spanish blood), who along with her husband, Tupac Amaru II, in 1780-81 led an important rebellion against the Spaniards in Perú that was the seed to the independence of the country a few years after. She was brutally executed as well as her partner, son, and many others. I wanted to talk through her story about the ongoing battle of women back then and in present society. In the exhibition, I transform her skin into mountains and her spirit into unstoppable water. That’s how powerful her legacy is. That is how powerful of a force we are, too.

And that’s how some phantoms of the past invaded my head and made me do that show. It was a celebration of a powerful woman, Micaela Bastidas, but also a celebration of all of us, in crisis and in victory. That’s also why I asked you, Marisol, to pose for me in the lake, as a reference for the painting Micaela lavándose las heridas en el río.

MM: When you asked me, I was blown away. I was also completely scared. When it comes to actually doing things in public, I'm a massive introvert. And I know if I had been asked by anyone else, I would have said no. But I trust you, Ceci. I also loved the story of Micaela Bastidas. We ended up having a great time that day.

Thank you for showing such a powerful history and one that in different forms seems to repeat itself for women in the present day. It is so important to study the history of women in an effort for us to understand how we can try to change the future. The show was powerful, in both your materials and the colors you chose to express the passion of who Bastidas truly was.

CJC: Thank you, Marisol. What projects and collaborations are coming up for you this year?

MM: In spring 2022 you and I will both participate in a project called Homecoming, which includes last year’s alumni artists from the Kates-Ferri Projects residency program. I am also going to be included in a group exhibition titled Look Again, curated by Michael Mosby, that opens on February 10 at the Historic Opera House in Hudson, NY. Beyond these exhibitions, I work on expanding my practice daily. It’s a daily practice of looking towards what's next.

What about you? What are you working towards in 2022?

CJC: I feel like my panorama is kind of open, although I have a few shows coming up too. I'm very happy I'm going to share space again with you, Marisol. I'm moving back to the U.S. fully at the end of March. So it’s a transitional year. I think that this year is very hopeful somehow, I guess because we feel like we are at least getting used to this virus now. So, we'll see what comes in terms of new projects and new subject matter for the work.

C.J. Chueca (Cecilia Jurado Chueca) lives between Lima and New York since 2003. Before this period she lived in different houses in Lima and in her first years she lived in Mexico City and Oaxaca. Her father migrated to Lima—the capital—from a small town called Muquiyauyo-Jauja where he was born. Chueca’s history as a perpetual immigrant has lead her to explore the concepts of home, territory, transition, multiculturality, uprooting and solitude. Focusing on talking about those lives that are still on the road (or without route) in the streets of the world.

Marisol Martinez is a New York based artist. Her abstract paintings explore the mechanisms of color and shape as tools of expression. Her process is intuitive, commanding color in limitless configurations– to record states of being while eliciting what exists within. The unguided stillness of each shape is a meditative process individually created to compliment the other. The interconnection of shapes and colors offer insight into Martinez unique experience of the world creating a visually spiritual vocabulary. Martinez has lived and studied in Paris, Miami and Los Angeles and received her BA from Parsons School of Design/The New School, NYC. She has exhibited throughout the US and abroad.