How to Survive the End of the World: Youth Literature at Puerto Rico’s Front Lines

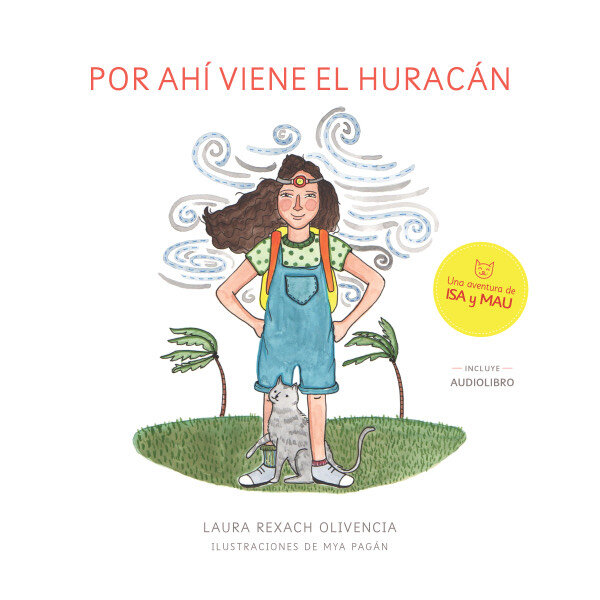

During El Verano de 2019, one creative act of resistance grabbed my attention like no other—when protesters decided to read “bedtime stories” to the Puerto Rican Constitution. Puerto Rico’s Police combat squad—la Fuerza de Choque—would begin dispersing tear gas around 11 pm each night. During those intense three weeks which ended in the resignation of Governor Rossello, the police said constitutional rights expired after 11 pm since “La Constitution Duerme/the Constitution sleeps.” Inventive protesters from La Clara, a feminist organization, and children’s authors such as Laura Rexach Olivencia organized a read-aloud protest where attendees symbolically and literally read to the Puerto Rican Constitution (1952) stories including the text of the Constitution and children’s books such as Olivencia’s Por Ahi Viene El Huracán (2017), which centers the lives of children before, during, and after Hurricane Maria. Youth literature and children’s literacy activities have a longstanding history at the frontlines of Puerto Rican politics and protests—a literary and cultural history my book project unearths, centers, and questions. Side by Side: US Empire, Puerto Rico, and the Roots of American Youth Literature and Culture (University Press of Mississippi, 2021) is as much about Puerto Rico’s history of youth literature and culture as it is about the history of what came to be known as American (US) youth literature and culture. This is a history of Puerto Rican public pedagogy that has much to say about surviving the uncertain and impossible.

Youth literature, media, and youth-led movements have played a prominent role in portraying the political and cultural relationship between the US and Puerto Rico—from the US acquisition in 1898 to Puerto Rican writer’s pleas for a place in US letters and culture. During the early colonial encounter, children’s books were among the first kinds of literature produced by US writers introducing the American public to the new colony. Youth literature and media, however, was also an important tool for Puerto Ricans to negotiate US assimilation and uphold a strong Latin American/Caribbean national stance. For example, elite leaders in Puerto Rico such as Manuel Fernandez Juncos intervene on US colonial schooling policies concerning English-Language school readers, yet taper down the anti-imperialist ideas of Eugenio Maria de Hostos and Ramon Emeterio Betances, both philosophers and organizers for liberation. Picture books, textbooks, and poetry anthologies later function as the building blocks of the commonwealth ideology, continuing into the 2000s with the resurgence of the current Puerto Rican picture book which contemporary authors such as Georgina Lázaro seek to break from any official island pedagogy. After Hurricane Maria and the recent earthquakes, writers such as Tere Marichal, Wanda de Jesus, Ada Haiman, Laura Rexach Olivencia have organized storytelling activities and mobile libraries on beaches, tent cities, and even the frontlines of protests, particularly given the collapse of support for public education and libraries. Side by Side peels back the neutrality, and benign celebration, in which scholars have often considered the tradition of Puerto Rican children’s literature, specifically its relationship to Puerto Rican and US governments. I analyze the nuances among generations of writers, particularly women writers and educators who ascribed to different ideas about the future and potential of Puerto Rican transnationalism, as opposed to the male dominant tradition of “insularismo” (Pedreira, 1934).

Confronting a Legacy of Silence: Generations of Resistance and Public Pedagogies

Researchers in Puerto Rican youth literature and literacy traveling to Puerto Rico quickly learn that the story of our field is entrenched and often unwritten, making fieldwork in the form of interviews with local librarians, booksellers, archival research, and visiting educational and mainstream bookstores invaluable.

Little if any critical analysis exists on contemporary Puerto Rican writers for youth beyond 1980 into the 1990s. There is also a paucity of scholarship on how past generations of Puerto Rican writers converge and contrast, particularly on political ideals. As writers Tere Marichal and Georgina Lazaro address, few books by Puerto Rican writers travel beyond the archipelago, hindering the opportunities for critical inquiry. In Puerto Rico, scholarship focusing on literature for youth as literature is also sparse, with few courses, if any, offered in undergraduate and graduate education, particularly as part of a literary foundation. Flor Piñerio de Rivera’s definitive resource, Un Siglo de Literatura Infantil Puertorriqueña / A Century of Puerto Rican Children’s Literature (1987) is often cited and guides the discussion of the field. Although Piñeiro de Rivera’s book outlines the bibliography of writers and details the history, her work ends at 1987 which time capsules how current researchers learn about Puerto Rican children’s literature. Writers in the evolving diaspora beyond the 1980s lose visibility in critical discussions for researchers and teachers, simultaneously, contemporary writers lose a kind of official designation as to what is considered Puerto Rican in Puerto Rico, especially when, at this point, we know the diaspora continues in both directions.

The “Big-Five” of the children’s publishing-industrial complex and literary agents seem indifferent to prospective authors and illustrators in Puerto Rico. Indeed, the bulk of these publishers contributions to young people’s literature in Puerto Rico comes through selling translations of North American books rather than investment in Puerto Rican talent. Youth literature as an industry and economy, as any other economy in Puerto Rico, demonstrates how wealth is extracted rather than retained (Edwards 2019). Yet, the publishing of Puerto Rican youth literature has always existed in economic, and to an extent, creative dependence on government initiatives—whether Spanish colonial, US colonial, or Puerto Rican commonwealth. The medium’s ties to school curriculum, and the lack of independent publishers publishing Puerto Rican books, made it especially vulnerable to the growing economic crisis, starting in the early 2000s.

Budget cuts to cultural institutions resulted in the paralysis of three of the main publishers of children’s books in Puerto Rico. According to Consuelo Figueras (2000), the loss of Editorial, the imprint of the Department of Education, accounted for a decrease of 18 percent of Puerto Rican books published. In her analysis, Figueras suggests a kind of self-determination for Puerto Rican authors and artists through children’s literature. She surveys the 1990s as a kind of renaissance for Puerto Rican children’s literature, citing a greater awareness among writers and publishers for the medium as an art form and the work of award-winning authors such as Georgina Lazaro’s El Flamboyan Amarillo (1996) and Fernando Picó’s La Pieneta Colorada (1991).1

However, Figueras’ praises “figures, historical events, natural environment, clothing, and values” as authentic and fixed suggests her adherence to cultural nationalism, an ideology guiding status quo Puerto Rican intellectual life since at least the 1930s and into the forming of the commonwealth. As Raquel Z. Rivera writes, in the face of US colonialism, cultural nationalism serves to portray a distinct Puerto Ricanness, though it varies depending on those utilizing it for the purposes of political ideology whether independentista in which it serves to sustain “a strong and distinct Puerto Rican culture theorized as unassimilable to US culture” or whether it serves a pro-statehood or commonwealth status (258). At the service of assimilationist politics, cultural nationalism becomes a force which shapes and restricts political, creative, gendered expressions in maintaining state power.

Upholding cultural nationalism has often meant upholding patriarchy, sexism, and racism, and suppressing revolutionary thinking. For example, Manuel Fernandez Juncos‘ adaptations of colonial readers for US colonial schools in the 1910-20s idealize stories about love the land, Spanish, and the Puerto Rican past, yet he doesn’t include past revolutionary thinkers such as Ramon Emerterio Betances. The lack of critique of children’s and young adult texts veils the aesthetic and political legacies of youth literature in Puerto Rico. Through Side by Side, I shift scholarly attention beyond cultural nationalism as a sole organizing factor and into how current and former generations of writers resist status quo narratives, subtly and outright.

Authors in Puerto Rico since the 1990s, such as Ada Haiman, reflect a deep concern about breaking from essentialist identities and official colonial pedagogies. The desire to create a self-governing body of work and representation remains, even as authors in Puerto Rico maneuver the creative and publishing process without access to the mainstays of publishing in the US, such as literary agents and independent presses. Contemporary authors strive to create literary works without the agenda of government-dependent public institutions which wax and wane depending on political party. The paucity of literary and sociocultural analysis given to children’s literature in Puerto Rico leads educators and scholars to accept these texts as forming a kind of neutral, yet distinctive tradition. Few linger on the ruptures between generations of writers and, indeed, schools of political thought on the colonial status of Puerto Rico, gender, race, and class—even in the face of legal policy favoring the censoring and criminalization of independence. How did authors supporting independence such as Isabel Freire de Matos maneuver within a children’s reading tradition, and government-dependent publishing industry, which favored colonial status and schooling? The Puerto Rican government through the Department of Education has certainly not viewed children’s reading materials as neutral, banning the circulation of materials deemed “anti- American” and “subversive.” For example, the work of Manuel Fernandez Juncos unites with Freire de Matos as cultural preservation, yet Juncos’ folklore was never banned while Ruben del Rosario and Freire de Matos’ ABC de Puerto Rico (1968), celebrated as a hallmark of Puerto Rican letters by Flor Piñeiro de Rivera’s Un Siglo de Literatura Infantil Puertorriqueña, was pulled from classrooms and libraries by a pro-statehood administration in 1968. Furthermore, toward the end of the 1990s, the school reader tradition ala Ángeles Pastor—upholding ideals of a Puerto Rican national literary tradition to youth—is retired from classrooms in favor of books in translation and, as in the US, texts centered on standardized testing standards. A parallel exists between the decline of children’s reading materials published and supported by the Puerto Rican government and the economic, environmental, political crisis that ensues by the early 21st century.

Yet, the story of Puerto Rican youth lit and culture as told in Side by Side traces a history of community-sustained, public pedagogies. From Pura Belpré’s storytelling without published books to the Young Lords Party’s community-created curriculum outside traditional school rooms to today’s Puerto Rico, post-Maria and earthquakes, even in a pandemic, with teachers and students writing their own stories and curriculum when the lights literally go out. This story speaks to the importance of alternative forms of storytelling beyond printing presses. The story of Puerto Rican youth literature highlights how the public pedagogy undergirding Puerto Rican Studies, and Latinx Studies to an extent, is one which has sustained a nationless state and systems of knowing beyond institutions—a pedagogy which would seemingly survive the end of the world.

Dr. Marilisa Jiménez García is an interdisciplinary scholar specializing in Latino/x/a literature and culture. She is an assistant professor of English at Lehigh University. She has a Ph.D in English from the University of Florida and a M.A. in English and B.S. in Journalism from the University of Miami. She was born in Bayamon, Puerto Rico. Marilisa’s research on Latinx literature have appeared in Latino Studies, 3CENTRO: A Journal of Puerto Rican Studies, The Lion and the Unicorn, and Children’s Literature. Her forthcoming book, Side by Side: US Empire, Puerto Rico and the Roots of American Youth Literature and Culture (University Press of Mississippi, 2021) examines the history of colonialism in Puerto Rico through an analysis of youth literature and culture both in the archipelago and in the diaspora. She is also editor of the new, third edition of Caribbean Connections: Puerto Rico (2020) published by Teaching for Change.

Works Cited

Figueras, Consuelo. 2000. “Puerto Rican Children’s Literature: On Establishing an Identity.” Bookbird. Vol. 38. No. 2 (23-27)

Juncos, Manuel Fernandez. 1911. Antologia Puertorriqueña: Prosa y Verso. New York: Hinds, Noble, Eldridge.

Rivera, Raquel Z. 2007. “Will the Real Puerto Rican Culture Please Stand Up?” None of the Above: Puerto Ricans in the Global Era. ed. Frances Negrón-Muntaner. Palgrave. 217-231.

Rosario-Perez, Vanessa. 2014. Becoming Julia de Burgos: The Making of a Puerto Rican Icon. Campaign-Urbana: Illinois Press.

Pedreira, Antonio. 1934. Insularismo: Ensayos de interpretación Puertorriqueña. Editorial Plaza Mayor.

Piñeiro de Rivera, Flor. Un Siglo de Literatura Puertorriqueña. Rio Piedras: Editorial Universidad de Puerto Rico.