Drawing Out: Gala Porras-Kim's Extractions and Reproductions of Museum Collections

Artists working in the vein of Institutional Critique elevate the context of display—whether a museum or gallery—from a mere supporting element to having its own inherent significance. In essence, rather than the art institution putting the artist on display, it is the artist who puts the art institution on display, subjecting it to examination and critique. Colombian artist Gala Porras-Kim embraces this inverted logic of institutional presentation, creating art that explores, in particular, the dislocation and museum presentation of archaeological remnants from Mesoamerica. Yet, Porras-Kim's approach does not tether itself solely to the discourse on repatriation. Instead, she proposes a different and nuanced return—one that considers how museums can help reconstitute some of the original, particularly sacred, aspects of artifacts in museum collections.

In 2018, Porras-Kim encountered two monolithic rock forms, or stelae, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) that were once at the summit of Tonatiuh itzacual (Pyramid of the Sun) (200 CE), the largest building in the Mesoamerican archaeological site Teotihuacán near present-day Mexico City. The stelae, now detached from their original context and ritual significance, probably served as offerings to the Sun God.

In response, Porras-Kim produced two replicas of the stelae and attempted to donate them to the National Institute of Archaeology and History (INAH) in Mexico, the institutional custodians of the Pyramid of the Sun. In a letter to Garibay Barrera, the national coordinator of museums and expositions at the INAH, titled Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements for the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacán (2019), Porras-Kim recommended placing the replicas at the original stelae's location to metaphorically restore or reconstitute the ritual elements of the Pyramid:

“Considering the lengths you have gone to reconstruct the exterior of the structures at Teotihuacan for the enjoyment of its visitors, I wondered if there have been any efforts to reconstruct the ritual elements that lay within the structures. There may not be an external motivation to reconstruct them since these are not accessible to the public, but if this were the case, I would ask you to consider reconstructing and/or replacing these elements that have been extracted such as these important monoliths, seeing as the fiction of the stones, or the audience of these internal sites, might not have been an earthy one.”

Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements for the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacán (2019) underscores the ethical implications of archaeological extractions and circulation. Since 2019, Porras-Kim has written to various museums and archaeological institutes (many of which are host institutions for her research fellowships, artist residencies, and exhibitions), inviting them to reconsider their approaches to controlled conservation and restoration. Her epistolary method illustrates the dialogical approach of her Institutional Critique, one that concentrates on the ethics of object care and conservation.

“Care,” a multifaceted term that takes on various forms within the art world, can shift in meaning across different contexts. In her written proposals and museum interventions, Porras-Kim widens the narrow scope of institutional care beyond mere physical preservation. By situating Porras-Kim's interventions within the broader framework of Institutional Critique, it becomes clear how she foregrounds the disparities between the originally intended destiny of sacred objects and the one imposed by secular institutions. Specifically, these are artifacts traditionally crafted for burial chambers or as offerings to deities that now find themselves as part of museum collections. Porras-Kim symbolically, if not literally, draws out objects from museum spaces, and with this practice, she subversively replicates and interrogates the norms of extraction, preservation, and presentation within the art system. This dynamic underscores the ongoing tension between artistic intentions and institutional validation mechanisms.

During her fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies, Porras-Kim conducted research on the collection of objects from the Sacred Cenote of Chichén Itzá, housed at Harvard Museum's Peabody Museum. Established in 1866 as the inaugural anthropology museum in the Americas, the Peabody received these relics from American diplomat and archaeologist Edward H. Thompson (1857–1935). Thompson dredged the Sacred Cenote over several years, extracting various artifacts crafted from ceramic, gold, jade, copal, flint, obsidian, shell, wood, rubber, and cloth, alongside human remains. In her letter "Mediating with the Rain" (2020) , addressed to Director Jane Pickering, Porras-Kim reflects on the disparity between the relics' original moisture context and their current storage conditions:

“These votive offerings were submerged as tributes to the Mayan god Chaac, and probably never meant to leave the cenote. … Some of the objects had been preserved over centuries because they were submerged in water in the cenote. Their current state of dehydration, caused by their extraction and maintenance by conservators, permanently changed their composition so now they are just dust particles held together through conversation methods. The Peabody is, in fact, preserving this dust as a shell of its past shape.”

Such a contradiction in the museum's intentions of object conservation subverts the authority of institutional paradigms of object care. Porras-Kim implies a certain hollowness in the museum’s stewarding, and her proposal to return the objects to the rain seems to represent a kind of triumph over the very conditions that engendered their fragility.

Porras-Kim also proposes reuniting these relics with their intended receiver. Precipitation for an Arid Landscape (2021), a sculpture crafted from dust collected from the storage area at the Peabody Museum (originating from the objects themselves) and copal (a transparent resin from the copal tree, often burned as incense in ceremonies and the primary material found in the sacred cenote). The sculpture constitutes approximately the same volume as the dredged objects from the Sacred Cenote at the Peabody. Rainwater saturates the installation, placed inside an epoxy box, as a symbolic reunion of the collected objects with Chaac.

Like most preservation practices, the act of watering is a deliberate and controlled process determined and overseen by the host institution, but in this case, water is run through machinery to disintegrate, rather than insulate the object. Precipitation for an Arid Landscape holds visual resonance with Hans Haacke's seminal institution-critical piece Condensation Cube (1963–1965), a transparent plexiglass case featuring condensation that accumulates and dissipates. Frequently cited by first-wave Institutional Critique artists, the cube mirrors the architectural context of the gallery space.* Responding to the conditions of the exhibition space, ambient light, and surrounding temperature, the condensation within Condensation Cube functions as a self-contained and self-regulating microcosm, mirroring the obscured atmospheric and conditioning mechanisms of the museum system. Both visually and conceptually, Condensation Cube and Precipitation for an Arid Landscape utilize transparency in their presentation, exposing the systems of the art world as an environment unto itself.*

In this particular context, the museum's methodologies as a presentational apparatus—such as labels, vitrines, pedestals, guards, and security systems that often exist at the periphery of the museum-goer's visual and cognitive experience—are brought to the forefront. In 1986, LACMA acquired 235 ceramic burial figurines and vessels (approx. 200 BCE–CE 500) unearthed from shaft tombs and burial chambers in Nayarit, Clima, and Jalisco, along the Pacific coast of Mexico. The seller, Proctor Stafford, mandated that LACMA prominently display his name alongside the object details wherever it exhibited these pieces. Subsequently known as the Proctor Stafford Collection at LACMA, Porras-Kim's project scrutinizes the prominence of the collector's name as the identifier for this diverse array of Indigenous artifacts when little information is available about them. Looters illegally seized the majority of archaeological artifacts from this region, thus scholars of ancient West Mexico rely mostly on salvage excavations performed on looted tombs. Accordingly, scholars have abstracted meaning, speculating about their context of use.

The Proctor Stafford artifacts reached the United States before the enactment of both the 1970 UNESCO convention safeguarding cultural property and a 1972 Mexican law asserting state ownership of all pre-Columbian artifacts. This raises a significant possibility that these artifacts are the result of looting. Porras-Kim suggested that LACMA openly acknowledge this historical context and revise the provenance, incorporating details such as "unnamed grave looters in West Mexico collection" and "deceased individuals of West Mexico collection," thereby providing a more accurate and transparent account of the artifacts' journey and acknowledging the complexities surrounding their acquisition.

Porras-Kim’s large drawing 78 west Mexico ceramics from LACMA collection: Nayarit Index (2017) renders the ceramics of Nayarit to scale and categorizes them by shape and size. While the methods of museum display and taxonomy are the focus of the artwork, 78 west Mexico ceramics from the LACMA collection goes beyond critiquing institutional nomenclature and moves toward recontextualizing the narrative surrounding the artifacts’ provenance and cultural stewardship, revealing textures of cultural displacement within the framework of museum convention.

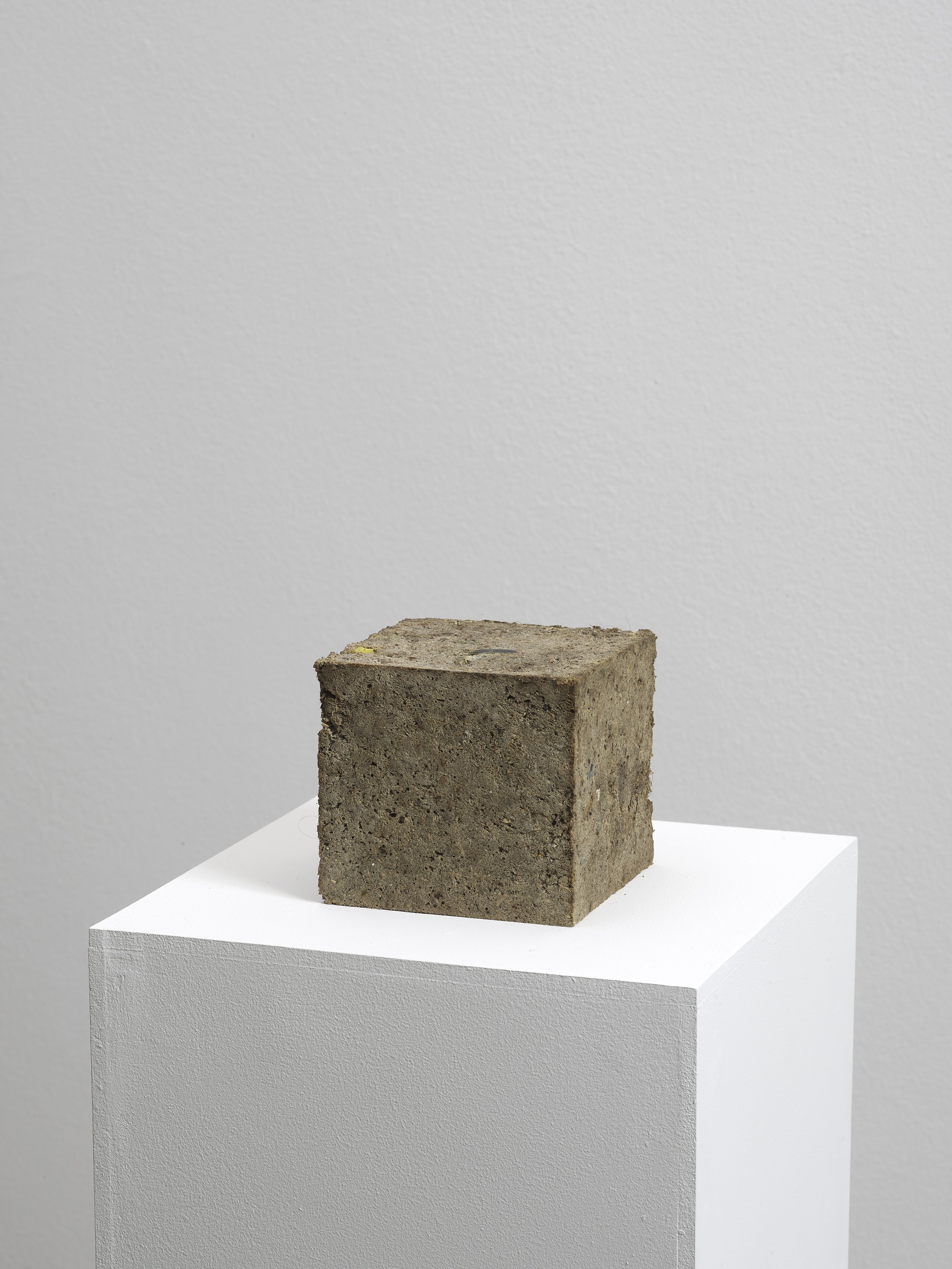

This capacity to highlight frequently overlooked facets of museography acts as a disruptive force, unraveling the aura of mystique that often surrounds the museum. For The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at the Met 1982–2021 fragment (2022), Porras-Kim retrieved the contents of a vacuum cleaner that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York used during the cleanup following the 2021 rehang of the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. The resulting compressed 9.5-centimeter cube encompasses dust, wood fragments from exhibited artifacts, and bodily detritus from museum-goers, predominantly skin and hair. Its reference to cleaning resonates with Mierle Laderman Ukeles's “Maintenance Art,” which emphasizes the frequently overlooked and undervalued maintenance work crucial to cultural spaces like museums. By carrying traces of exhibits out of The Met museum, it participates in what art historian Marv Recinto identifies as a form of “deaccessioning act” that “also converts the unwitting attendee into an ethnographic object in a manner that parallels the decisions of encyclopedic collections to put the remains of ancient humans on display.”

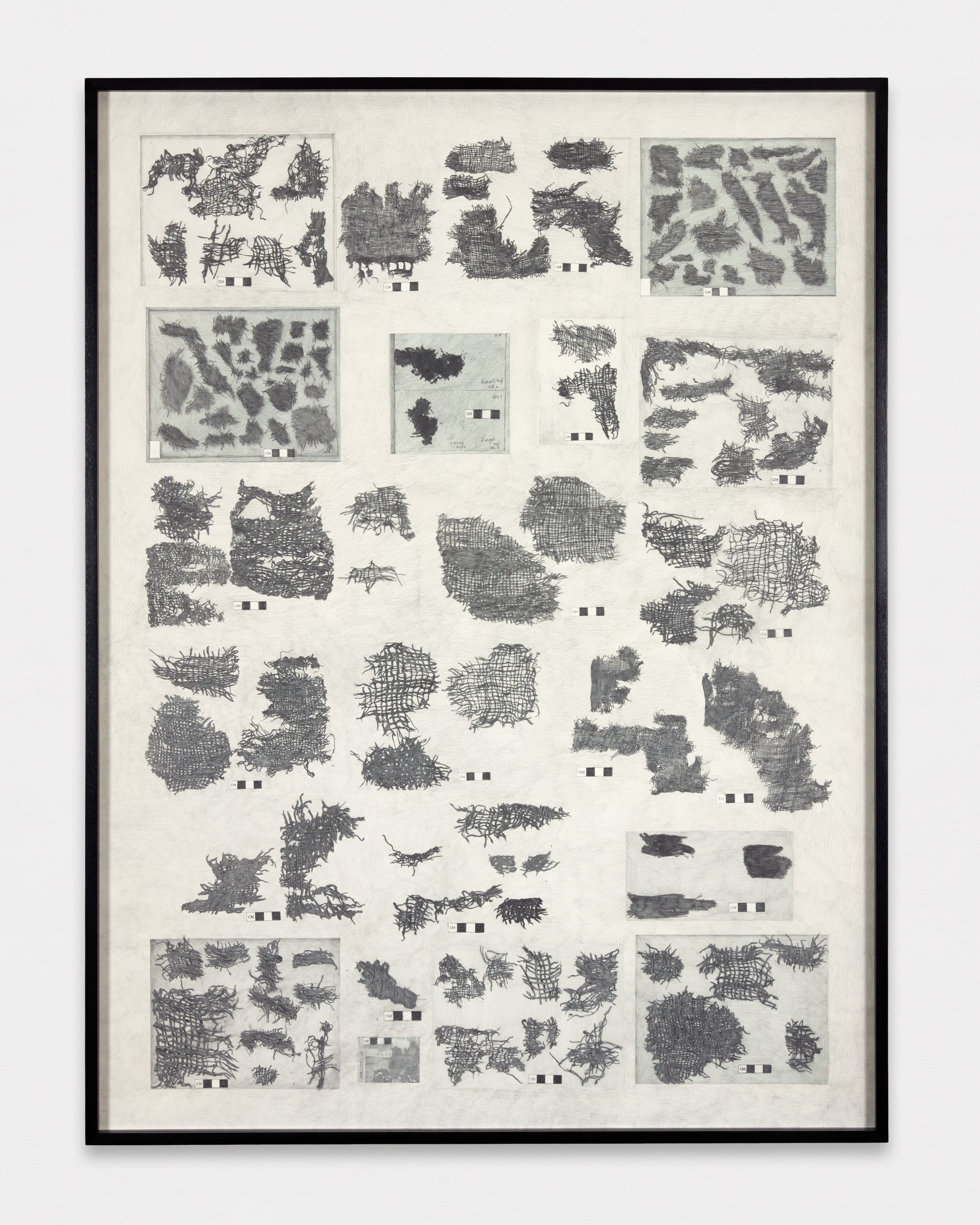

Where The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at the Met 1982–2021 fragment involves a physical extraction from what lies inside the museum’s built frame, Porras-Kim's visual replications of museum collections employ a symbolic tactic of extraction or drawing out. Take, for example, 122 Offerings for the Rain at the Peabody Museum (2021), another piece stemming from her research at the Harvard institution. This work inventories textile offerings to Chaac, stored out of sight and conserved by the museum. Porras-Kim captures these offerings through schematic graphite drawings, visually replicating the textiles by using scratchy graphite marks to mimic the woven threads. Porras-Kim’s Offerings echoes the decolonial spirit of Fred Wilson’s seminal intervention at the Maryland Historical Society, Mining the Museum (1992).* Working from the museum collection and offices, Wilson brought into the galleries a variety of texts, recordings, and objects about the local histories of African Americans and Native Americans, typically relegated to storage. With this gesture of retrieval, he was able to spotlight these local histories and dismantle the conventional museological narrative as a narrowly ideological project.* We may find resonance in how Porras-Kim repositions collections, providing visibility to overlooked or intentionally hidden aspects of the museum. Indeed, Offerings is a kind of art that works with and plays against the logic and systems of museums by rescuing the visibility of Latin American artifacts, even those paradoxically already within a museum collection.

Porras-Kim’s artistic gesture not only restores these items through reproduction but also, now that the MoMA has acquired the drawings, reintroduces them into the art museum collection as part of a reconstructed archive. In this sense, she draws them out of obscurity and brings attention to objects that are typically kept away from the public eye. However, do Porras-Kim's visual renderings of artifacts challenge existing systems of collecting and aesthetic validation, or do they inadvertently align with them?

By rendering these objects “visible” through representation, there is the risk of reinforcing Western visual-centered valuation and aesthetics, potentially diverging from the native values and cultural practices associated with the artifacts.* This paradox heightens when considering installations like Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements for the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacán which seek to restore ritualistic function, against drawings from her Offerings series which serve as visual proxies. The reintroduction of artifacts, even in the form of drawings, into art museum collections could inadvertently perpetuate the Western museum's tendency to prioritize visual display over the performative or ritualistic elements inherent in these artifacts. How can agitation through cultural production prevent itself from being neutralized into, as writer and editor Andreas Petrossiants asks, a mere spectacle of absorption?

The recognition and embrace of Porras-Kim's work by prestigious institutions might be viewed as a validation within the very systems she critiques. Even if only a few of her letters to museums have directly elicited responses from the recipients, the artist's interaction with institutions, while agitative, is not inherently adversarial. LACMA and MoMA have acquired Porras-Kim’s drawings of the Proctor Stafford Collection. The Peabody Museum went so far as to offer to loan an original cenote fabric fragment for Porras-Kim's exhibition of her textile drawings in the Radcliffe gallery. This assimilation into existing art market dynamics raises pertinent questions about the institution’s capacity to accommodate such critiques, delving into what Andrea Fraser coined "institutionalization of institutional critique."

Ultimately, Porras-Kim relies on institutions to play their part—inviting her to study their collections and hosting her interventions—so that she can play hers. In this dynamic, Porras-Kim simultaneously relies on and critiques the systems that govern cultural production and dissemination. This symbiotic relationship, while seemingly paradoxical, highlights the inherent tension within Institutional Critique. By operating within the bounds of the institution, Porras-Kim gains access to resources and visibility that enable her interventions to have impact. Still, in drawing out items from a museum, she allows these objects to symbolically move in and out of the bounds of the institution, affording them the same kind of mobility and agency she has as an artist.

* In 1976, art critic and artist Brian O'Derthy introduced the concept of the "white cube," which encapsulates the aesthetics and ideology associated with the increasingly popular, clean, artificial, and white look of gallery spaces. This term, at first radically self-referential, has become widely adopted in the art-world lexicon.

* However, if Condensation Cube primarily questions the stability of the status of “art” and its dependence on external conditions within the art world, Precipitation for an Arid Landscape subverts institutional authority in determining the preservation of cultural artifacts.

* The Maryland Historical Society, now rebranded as the Maryland Center for History and Culture, holds the largest collection of Maryland culture in the state, boasting more than 350,000 objects spanning presettlement to the present day.

* The titular Mining the museum, a clever allusion to extracting objects from the museum, becomes a generative excavation or retrieval of forgotten African-American artifacts, “bringing to light a history and cultural presence buried beneath layers of neglect and deliberate exclusion.”

* For more on the issues and consequences of an overwhelmingly western standard of art applied to pre-Columbian art, see Carolyn Dean’ “The Problem with the Term ‘Art’”

Clara Maria Apostolatos is a historian and writer of Latin American contemporary art and the 2023-34 Kress Interpretive Fellow at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. She has assisted with exhibition and interpretive programming at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Center for Italian Modern Art, and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Her other curatorial work includes "Kenneth Kemble and Silvia Torras: The Formative Years, 1956-63," organized through the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art. Her writing appears in Burlington Contemporary, The Brooklyn Rail, Artsy, Cultured, and Vistas: Critical Approaches to Modern and Contemporary Latin American Art.