Crisis Projects: 25 Years of AgitArte in Puerto Rico and The Global Diaspora

“What is it that we’re going to do? What’s the ima… without ignoring our limitations, but what is our best political imagination towards a completely changed landscape?” Jorge spits out ideas in rapid-fire, colloquial Puerto Rican Spanish, interrupting and correcting himself as he goes, warning me repeatedly to ask him to slow down if necessary.

We’re sitting on the breezy front terrace of the Casa Taller Cangrejera, a two-story mid century cement house in a quiet part of Santurce, the barrio of San Juan where Jorge was born and raised, that serves as AgitArte’s workshop and headquarters. Turning 50 in a few days, AgitArte founding member and Co-Director Jorge Díaz Ortiz is a veteran of many movements—and not just in Puerto Rico, where he returned in 1999 after spending the whole decade as a college student and community organizer in New England. Growing up in an independentista family, during his time there, he was further radicalized through his work with working-class Latinx and African American communities.

Jorge has just referred to AgitArte’s best-known project—its street theater troupe, Papel Machete (itself an independent group supported through AgitArte’s broader Popular Education and Performance Project)—as a “proyecto de crisis” (“crisis project”). The phrase strikes me as curious, so I ask him to elaborate. He goes on to describe what he calls the “economic defeat of the working class” as a corollary of the austerity measures that accompanied the “fiscal crisis” officially announced in 2006 (the year Papel Machete was founded): “It’s a conclusion I’ve reached, that our work is cheap—papier-mâché—we have no resources… now we have a little bit of resources, we have a space, but we never expected that to happen.”

Resources or not, few initiatives have left as much of a lasting imprint on the visual and affective archives of the political landscape of this U.S. Caribbean colony (or “unincorporated territory”) over the last quarter century as AgitArte. If nothing else, the image of a giant papier-mâché student towering over a crowd of marchers, or swaying to the beat of the drums in one of the many videos produced during the 2010-2011 student strike at the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), will strike a familiar chord with anyone who has paid attention. El Estudiante Militante (“The Militant Student”) is one of several giant puppets produced by Papel Machete over the years.

Street theater, however, is only one aspect of the collective’s broad-based and multifaceted popular education efforts. Founded in Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1997, and reinventing itself over the years to meet the demands and challenges of the changing terrain of local and global anti-colonial and anti-capitalist struggles, AgitArte has grown into a number of geographically dispersed projects tied together by a network of “radical solidarity” amongst like-minded artists, activists, and collectives.

Over the summer of 2022—shortly after the collective turned 25—I had open-ended conversations with Jorge and two other key AgitArte members: full-time Co-Director Sugeily Rodríguez Lebrón, and art professor Javier Maldonado O’Farill (Papel Machete co-founder and member of AgitArte’s Board of Directors). From these conversations, I have pieced together a timeline of the period that illustrates how the group’s emergence and mobilization of political affect and memory has been intimately entwined with Puerto Rico’s ongoing crises up to the present, including the 2019 Uprising that ousted governor Ricardo Rosselló.

To Agitate You/rself`

As its name indicates, AgitArte (a portmanteau of “agitation” and “art” that also literally translates as either “to agitate you” or “to agitate yourself” in Spanish) was from its origins directly influenced by agitprop theater and poster art. Jorge mentions Bertolt Brecht, along with Paulo Freire, Amílcar Cabral, Antonio Gramsci, the Black Panthers and his own mother—a “revolutionary from the heart”—among his influences. Other self-evident influences include commedia dell’arte, a long tradition of Puerto Rican political poster art, and the radical “guerrilla” theater groups inspired by Augusto Boal’s “theater of the oppressed” in the 1960s and 1970s.

AgitArte defines itself as “an organization of working-class artists and cultural organizers who work at the intersections of race, class, gender, sexuality, and ideology.” Its members are unequivocal about its anti-colonial and anti-capitalist character. As Sugeily (or Su, as her friends call her) put it bluntly, “We aspire to the total decolonization of Puerto Rico” (emphasis mine). As the adjective “total” implies, she envisions transformations beyond juridical independence alone:

It means being independent from the U.S. and also means building, from the grassroots [“desde las comunidades”], systems that truly work for us. The possibility of everyone having an education, a roof, food, the ability to live a healthy life, access to healthcare. In general, what I aspire to is a dignified life for us and for coming generations, now (emphasis mine).

“In other words,” I suggest, “a radical change in the economic and political system.” “Yes,” she replies without missing a beat.

AgitArte’s radical politics—already present at the group’s origin—were further nurtured by its political milieu in Puerto Rico (or, as Jorge only half-ironically calls it, mimicking academic jargon, its “organizational ecosystem”), composed of various relatively small radical Leftist cadre organizations (including a few other “cultural” initiatives, such as musical groups and street muralists) active within the labor movement, the UPR, and a handful of urban communities during the 2000s and early 2010s. While its own original core consisted of artists and community activists on the “periphery” of this relatively closed “ecosystem,” eventually Papel Machete also drew “organized” militants, especially from the youth and student organizations.

Beyond the immediate ideological milieu, crisis conditions during this period led to the proliferation of localized conflicts and movements dispersed throughout the colony. Jorge is emphatic that AgitArte doesn’t see itself as “external” to these struggles: “I think Papel Machete is a community group. It’s just that it’s not a geographic community.” This notion is sustained by a theory of acompañamiento, (“accompaniment”) or support for already existing struggles, “in order to amplify their media and arts capacity.”

Later, Javi further elaborates this vision with an example. Pointing at the wall behind me, he notes: “[I]n 2008 we did a first tour of that piece shown in that photo up there, En mi barrio se puede [“In my neighborhood, we can”], our first short puppet piece.”

We went to several communities, but they were spaces that were already organized, where something was already going on… We didn’t parachute in to tell folks what to do. Something was already happening, and we just joined, and came out in support, or to agitate if it was something heavier.

He accompanies the point with an anecdote about the surprisingly successful outcome of one such performance, as a result of which the crowd got so riled up, they tore down the makeshift barricade a developer had put up to restrict access to a local lighthouse (except through his restaurant). “We really did agitate [that time]!” he says with a smile.

When I spoke to Su a few days later, she offered several additional examples. We laugh as she tells the story of how Papel Machete members playing “villainous” characters were once chased by a crowd that grew too “passionate.” But, she insists, these experiences are generative as well:

[W]hat they do with what they receive from us is part of the work we want to accomplish, which is not just to generate an emotion, it’s also generating that questioning. You know, ‘look, question this thing that’s going on,’ and, ‘what can we do to change this situation?’

An Emergent Timeline

In 1997 Jorge—then a recent graduate of Emerson College with a degree in mass communications—found himself working in Lynn, a working-class city north of Boston, for a nonprofit organization through which he founded his first popular/political theater group. The experience proved to be a valuable education in institutional cooptation. When the higher-ups insisted that the group promote candidates in local elections, “I told them to go to hell and we continued the project, without any money.”

From this refusal, AgitArte was born. Remaining active in Lynn through the early 2000s, the group “facilitated creative workshops, produced street performances, monthly spoken word/poetry/music ‘speak-outs,’ and cultural events dealing with issues affecting working-class youth and youth of color in the community.”

Jorge, however, moved back to Puerto Rico to care for his mom, who had fallen ill and returned to the colony after several years as a community organizer in the Boston area (where she had migrated in 1991, following her college-bound son’s footsteps). For the next year, he was employed by EducArte, an independent nonprofit group financed by a program of the San Juan Mayor’s Office. Through this experience, he first came to know the communities of Caimito, a large, historically Afro-Puerto Rican semi-rural barrio of San Juan which, like many other communities at the time, was facing the combined threats of displacement and environmental injustice. Residents had recently posed a partially successful legal challenge to the destruction of the Chiclana quebrada (creek)—one of San Juan’s most important natural ecosystems and aquifers.

It was also at this time that Jorge first met fellow santurcina Maryann Hopgood, a professional graphic designer who had given up her successful business to found and direct EducArte. That project, however, came to an abrupt end after San Juan Mayor Sila Calderón won the governorship in 2000, in what turned out to be another abject lesson in electoral machine politics. No longer needing the publicity, the Mayor’s Office wrapped up: “in the end they seized all of Maryann’s property . . . they fired everyone, seized all the material.”

Not long thereafter, AgitArte Puerto Rico was born, thanks to a three-year grant that Jorge was able to secure. With the help of a community leader he had met through his previous involvement, Jorge developed a popular education program for youth in the most deprived sectors of Caimito. With the program’ s support, young community residents self-organized protests against displacement and environmental degradation, and painted murals in strategic locations such as bus stops and a concrete wall separating the barriadas from recently built middle-class walk-ups. These projects caught the attention of community leader Haydeé Colón, who approached Jorge, starting a fruitful collaboration.

After the funds sustaining AgitArte’s work in Caimito had dried up a few years later, Colón brought Jorge to his first meeting of Santurce No Se Vende (Santurce Is Not For Sale). There, Jorge reconnected with his former boss, Hopgood, who was now leading another fight in their mutual home barrio. She and other residents of San Mateo—the Black-founded historical heart of Santurce—faced plans to seize their homes through eminent domain, in order to “revitalize” the area surrounding the brand new Puerto Rico Art Museum (MAPR) by replacing them with luxury towers. Although the fight was all but lost at that point, Jorge and a group of five or so unpaid collaborators from the Caimito project (most still in AgitArte’s orbit today), decided to “give it our all, in order to make the most amount of noise possible.” At the heart of the effort was the Museo del Barrio, where AgitArte was given office space: Hopgood’s family home, refashioned into a public archive of San Mateo’s history, and named intentionally to evoke a counter-narrative to the elitist vision behind the MAPR.

Another important piece of Santurce No Se Vende was New Zealand-born mask-maker and puppeteer Deborah Hunt, whose travels throughout Latin America brought her to Puerto Rico in the late 1990s. From Hunt, Jorge and the others learned the papier-mâché puppet- and mask-making techniques that would become Papel Machete’s signature style. It was also through Hunt that Jorge first met Su, who had been working with Hunt in the administration of Yerbabruja Theater in Río Piedras, near the flagship campus of the UPR. Su, who had been a student activist at the Cayey campus, would be invited to join Papel Machete in 2009, after several years of collaboration.

The other main ingredient that coalesced with AgitArte to form Papel Machete was Indymedia Puerto Rico. Founded by former student activists involved in the renewed movement to shut down the U.S. Navy base and live-fire training range on the island of Vieques, Indymedia PR was the local node of the global Indymedia network. In addition to providing an online platform for activists as an alternative to corporate media coverage of protest events, the Indymedia PR collective produced its own original news content in the form of reports and photo essays. Javi first went to a Santurce No Se Vende meeting to report on the movement for Indymedia PR. He and other collective members soon began attending the mask-building workshops, where they mingled with the AgitArte crew. From these interactions, the idea emerged to “do something different on the street” the following May 1st, using the techniques learned from Hunt.

Empowered by the success of the anti-Navy movement on Vieques (the base and bombing range shut down permanently on May 1, 2003) and drawing from its occupation tactics and environmental and anti-displacement ethos and identity, Puerto Rico’s decades-old beach access movement (Fig. 22) resurged as well, most visibly in an encampment known as Playas Pa’l Pueblo (“Beaches for the People”), which occupied a stretch of the beach in the Isla Verde tourist area, where the Marriott Hotel had illegally secured permits to expand its parking lot.

In April 2005, students at the UPR-Río Piedras began a month-long strike against tuition hikes—a much-maligned but ultimately prescient predecessor to the more widely supported UPR strike of 2010-2011. Jorge sees the confluence of the three movements—Santurce No Se Vende, Playas Pa’l Pueblo, and the 2005 strike—as a “historical moment” underlying the emergence of Papel Machete. Javi, who covered all three as an Indymedia PR correspondent, describes it as a “triangle” that allowed him to become more involved in ongoing struggles.

Papel Machete

After two months of mask-building workshops, Papel Machete saw the light of day on May 1, 2006—International Workers’ Day (historically celebrated by Puerto Rico’s labor movement, despite the colonial imposition of “Labor Day” in early September). The May Day demonstrations of 2004 and 2005 had already seen a slight resurgence of confrontational tactics amid simmering labor tensions, the looming fiscal crisis, and the UPR strike. In 2006, it came in the midst of a local government shutdown provoked by a legislative stalemate over a proposed sales tax intended to finance the repayment of Puerto Rico’s “extraconstitutional” debt. Legislators from the governor’s party favored the percentage proposed by the governor, while those from the other major party favored a different percentage. A large march in late April called for by TV and radio personalities—ostensibly nonpartisan, but supported by the governor’s party and largely blaming the opposition—demanded a resolution (a dissident faction of the opposing party eventually agreed to the governor’s proposal, ending the shutdown). The Left and the more militant labor unions instead rejected the sales tax altogether as regressive.

It was in this context, and in support of the latter demand, that the still nameless street theater group was brought into the world, with a street performance, titled Los vividores del pueblo. The piece involved five cabezudos (characters played by performers wearing large papier-mâché heads)—Government, Banking Sector, Developer, Church, and Corporation—who “live[d] off the people” and were responsible for the financial crisis.

Jorge’s recollection of that day is not an altogether fond one:

That day, I say we really messed up in the street. It was horrible, our people were terrible performing, it was raining . [One member] took off his mask, ran away. Because that day there was heavy confrontation [with police]. We had to all stay together, because we didn’t know what was going to happen. I didn’t know anyone . . . We were all looking out, just to not get beat up. We were wearing masks… I had never done street theater with masks. I had done very few things in the street, and never at protests.

All the same, there was a collective decision to turn the experience into a long-term project: “As horrible as that day was, the energy of performing in the streets was such that we said, ‘Let’s get a project going’.”

Such a project would need its own name, which came to Jorge almost immediately. On September 23, 2005, Filiberto Ojeda Ríos, leader of the clandestine pro-independence organization known as the Macheteros, had been gunned down by the FBI. Years earlier, Juan Carlos Ortega, a Colombian poet and activist who had helped found Jorge’s first political theater group back in Massachusetts, had written a poem to Puerto Rico’s liberation struggle, in which the Macheteros were referenced and papier-mâché was deployed as a central metaphor: “con papel y con machete armaremos el futuro” (“of paper and with machete shall we build/arm the future”). Papel Machete thus seemed an obvious choice as a moniker for the emerging anti-colonial, anti-capitalist agit-prop street theater group.

Over the next decade, Papel Machete developed its repertoire as the crisis unfolded. One of the group’s most widely seen and best-remembered acts was the Ninguno Pa’ Gobernador (“Nobody for Governor”) campaign during the 2008 elections.

It’s a Project that begins as a joke between [another Papel Machete member] and I. It was like: “Ninguno [none of the candidates] this, that”…it began verbally: “Ninguno comes from the people” […] We were even on [comedian Antonio Sánchez] El Gangster’s show, you know, they insisted, they called us. Remember, Ninguno is a joke, so it has the perfect combination of what reaches Boricua popular culture…of course, there’s a [political] basis for all this: when we did it, half the country was already not voting. It’s not a question of just vacilón […] We had masks, flags, signs, we had everything, folks wearing t-shirts. We appropriated that electoral aesthetic too, to bring the message.

Despite its spontaneous origin, Jorge recalls Ninguno as one of Papel Machete’s few initiatives that was carefully planned (rather than “organically” responding to events in the heat of the moment). Humorous wordplay in the idiosyncratic style of popular Puerto Rican vacilón quickly became a detailed campaign for electoral abstention—and, Jorge adds, “an invitation to organize in the streets and communities as the only real option for the working class”—echoing what at the time was in fact a growing sense of a lack of true alternatives.

Other, less known Papel Machete acts deployed a variety of theater and street theater genres and techniques, including street performances, puppet and shadow puppet theater, toy theater, cantastorias (“story singer” in Italian; a genre in which a narrator tells or sings a story while gesturing to a series of images), crankys (or crankies; a technique that involves a roll of paper with painted images that tell a story, that is gradually “cranked” or pulled into view), and scrolls (similar to the cranky, without the crank, and involving audience participation). Throughout the years, these have been performed in plazas and other urban public spaces, at demonstrations, or for communities facing displacement, police violence, or environmental injustice.

The group has also developed numerous indoor theater pieces presented within a variety of cultural spaces both in Puerto Rico and abroad. On the importance of such spaces as a platform for, Javier notes how the annual Titeretada, an independent puppet festival,

pushes us to create these short pieces, and to continue exploring more media, more aesthetics, because it positions us right next to puppeteers and companies like MaskHunt and “Y No Había Luz”. Obviously, we had to be there [. . .] It’s a good cultural space, and in some way we’re helping to radicalize it. We’ve had a very good reception amongst that public, and we started noticing how some of the other companies’ performances went more progressive, started saying something.

Papel Machete has been on the organizing committee of the Titeretada since its inception in 2008.

Without a doubt, however, it is the giant puppets which have left Papel Machete (and AgitArte’s) most visible and lasting mark on Puerto Rico’s political and cultural landscape, starting with El Gigante Proletario (“The Proletarian Giant”) on the group’s one-year anniversary on May 1, 2007. The following year, 2008, saw the birth of La Maestra Combativa (“The Combative [female] Teacher”) in support of a week-and-a-half long teachers’ strike demanding improved conditions and opposing the introduction of charter schools, which paralyzed most of the colony’s public schools. Fifteen years later, the Maestra can still be seen at mobilizations against school closures, further cuts to teachers’ pensions, and privatization and austerity policies in general.

During the 2010-2011 UPR student strike, Papel Machete members (some of whom were also students) assisted strikers in the construction of El Estudiante Militante, which became the internationally recognized symbol of that struggle. Encompassing these two major processes—the teachers’ and UPR student strikes—from 2008 until 2014 the giant puppets were usually accompanied by Papel Machete’s marching band, which often also participated in large marches on its own, identifiable not just by its musical instruments and distinctive black-and-red “uniforms,” but also by large, colorful signs and placards.

Around 2014, the Puerto Rican radical Left entered a period of profound introspection. Infighting, shifting visions and priorities, and the untimely deaths of historical leaders led to the weakening, disappearance, or transformation of the political cadre organizations that formed Agitarte/Papel Machete’s “ecosystem.” Repeated disappointments after two decades of neoliberal offensive made it clear that the wider movements of the older generation would not recover their lost militancy. After repeated tuition hikes and other institutional changes, students, who had been the backbone of the radical Left during this period, no longer had enough time to dedicate to activist work, or were graduating into, and becoming parents in, an extremely hostile labor environment. Like hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans during this period, many were forced to migrate, as hundreds of thousands had decades before.

In Papel Machete’s case—perhaps more so than for other groups, given the labor- and material-intensive costs of the work—survival hinged on the capacity to financially sustain a tight core of full-time artist-activists with a wide range of occasional collaborators, rather than the formal membership of about fifteen it had at its peak. More priority began to be given to AgitArte (already incorporated as a non-profit) as the fiscal sponsor and “broad tent” for a series of projects, of which Papel Machete is just one. The Casa Taller—then at a different location (the structure that houses it today was purchased in 2020)—became a more formal headquarters and working/living space for a few core members and visiting collaborators. Ironically, while according to Javier, “Papel Machete is what [kept] AgitArte alive for so many years,” Jorge now notes that “surely Papel Machete would have disappeared if it wasn’t for AgitArte.”

Exercising Independence

In 2016, after Puerto Rico’s governor declared the colony’s $74 billion public debt “unpayable,” the U.S. Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; “promise” in Spanish), which among other things created an unelected, unaccountable 7-member Fiscal Oversight and Management Board (known locally as la Junta) named by the U.S. President, and with the power to review and overturn all local financial legislation, propose “adjustment plans,” and initiate a local bankruptcy process. Opposition to PPROMESA and the Junta took various forms, most visibly in the eventual emergence of Jornada: Se Acabaron las Promesas (“Promises Are Over” Campaign; referred to simply as “Jornada”), a group that combines confrontational tactics with highly visible, intentional performativity, in many ways inspired by Papel Machete. The two groups have collaborated closely from the start and continue to do so.

A year later, on September 20, 2017 Hurricane María devastated the colony, drastically compounding the uneven structural vulnerabilities and eroded state capacities produced by two decades of deindustrialization, aggressive neoliberalization, and fiscal crisis, now augmented by the Junta’s draconian prescriptions. The Casa Taller instantly became a kind of soup kitchen and supply hub for the immediate AgitArte/Papel Machete community, their families, and neighbors. As Javier, who lives nearby, recounts:

I was able to deal with [what was going on] mentally, because I would wake up, maybe have a quick breakfast, and head over [to the Casa Taller], in order to not just sit there at home all messed up [with nothing to do].

Soon, a conversation with fellow Left activist Giovanni Roberto, who a few years later had started a mutual aid non-profit initiative on UPR campuses to feed hungry students, led to AgitArte taking on a much bigger role.

Casually dropping by the Casa Taller for a rest stop on a particularly chaotic day two weeks after the storm, Roberto shared the work his organization was doing in the town center of Caguas, setting up what was to be the first Centro de Apoyo Mutuo (CAM; “Mutual Aid Center”). As Su recalls, “he said to us, ‘it would be great if Papel Machete could stand in the lines and do some theater or something to communicate what’s going on [to the people lining up for food and other necessities at the CAM].”

So we had a meeting right then and there, and began to develop material, and put out a cantastoria called Solidaridad y sobrevivencia para nuestra liberación (“Solidarity and survival for our liberation”), which consists of two panels in which we explain what was happening in the country, the withholding of aid, the interminable lines everywhere, the uncounted deaths, and also how people were lifting up their communities and surviving through self-management, solidarity, and mutual aid. And denouncing how the state had failed, how it wasn’t just a crisis because of the catastrophe, but also because the system doesn’t work.

The human-made catastrophe itself thus created a “political opportunity” not just in the form of what Su calls a sense of “clarity” amongst the general population, but also in the very physical spaces where activists stepped in to fill the vacuum left by the state’s inability or unwillingness to provide basic services.

Beyond the accustomed political agitation through Papel Machete, ongoing conversations with Roberto and other activists from other organizations led to the creation of more CAMs throughout the main island of Puerto Rico, and eventually a (relatively short-lived) Mutual Aid Network. Su narrates a striking summary of the multiple types of activity and emotional stamina this entailed:

Right after María, our space, the Casa Taller, became a central aid collection and distribution hub. Many people began to send things from the U.S. and . . . Anyway, the CAMs began to take shape in many parts of the [main] island, many comrades in their own communities, and we helped facilitate through the aid that was arriving. Food for the CAMs that were slated to become soup kitchens, or through the purchase of equipment, materials . . . We did a lot in that sense [. . .] For me, it was exhausting, but you know what? At the time, there wasn’t even time to process what was happening because we were doing stuff all the time . . . Organizing, coordinating, finding funds to support the comrades who were running the CAMs, finding money so those folks could continue doing things, because there was no money coming in, people were unemployed. The search for funds . . . to try and provide work for artists to generate art denouncing what was going on.

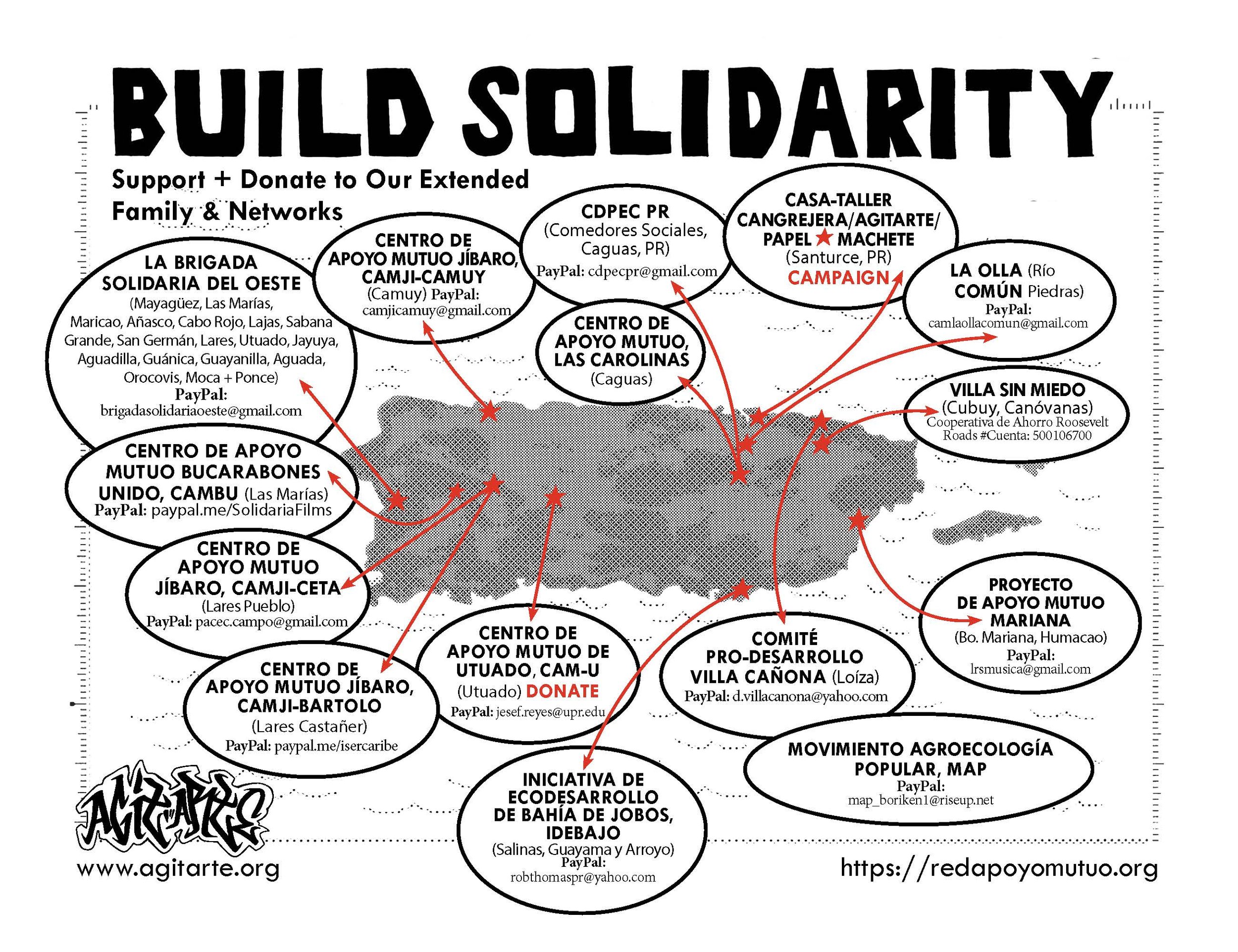

Together with Jornada, AgitArte helped run two San Juan area CAMs (in addition to the Casa Taller itself, which continued to provide three meals a day for 15-20 people for six months), and Su’s contacts in Villa Sin Miedo—a historically combative land rescue community in Canóvanas—led to setting up a CAM there as well.

María also led to a series of new non-theatrical visual arts projects. One was the creation of Datos y dibujos a “rapid response network” of graphics for online distribution, illustrating the extent of the human toll caused by the neoliberal colonial state’s failed response. This initiative lasted for the year or two following the hurricane and was reactivated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another was the production of physical posters using printing techniques in the traditional Puerto Rican political poster-making style, supporting the CAMs or denouncing various ongoing injustices. The originals are displayed in the Casa Taller’s library, and some—like Javier’s Aquí servimos solidaridad (“We serve up solidarity”)—have been featured alongside historical posters in public exhibitions at the UPR’s Museum of Anthropology and Art and other venues.

Reflecting on the group’s commitment to “total decolonization,” Jorge referred me to an article he had written on the mutual aid efforts that followed Hurricane María. Despite his protestations to the contrary, the brief but theoretically sophisticated paragraph where these ideas are laid out is worth reproducing in its entirety:

Nonetheless the exercises of self-governance, or as we called them ejercicios de independencia, experienced in the CAMs and when people came together to oust an abusive colonial governor, are great examples of a transformation that’s possible when the material conditions and the will of the people come together. The fissures created after catastrophes in the management of emergencies by the state can create conditions for breaks in the hegemony of our colonial state and permit for new structures of governance and power. These are much needed exercises of autonomous action and organizing, which inform practices and ideas of future alternatives to the organization of the state and society.

Jorge and AgitArte are not alone among contemporary activists making this kind of link in the context of Puerto Rico’s recent history, which synthesizes centuries of revolutionary theory and practice with similarly long-standing traditions of thinking about the politics of disaster. What stands out here is the serious attention to not just the “breaks in the hegemony of our colonial state,” but also to potentialities for creating “new structures of governance and power” and “future alternatives to the organization of the state and society.

Diasporic Arts

AgitArte also continues to collaborate with numerous individuals and groups beyond Puerto Rico’s geographical limits. For instance, the group maintains close relationships with individual artist-activists and popular education acts through mutual contact with the Vermont-based Bread and Puppet Theater. Over the years, these have been part of AgitArte’s extended network, staying in residence at the Casa Taller or contributing “rapid response” projects.

In 2014, Papel Machete collaborated with the Brooklyn-based community organization El Puente to produce La Madre Tierra (“Mother Earth”), an 18-foot high puppet that was a centerpiece of the 300,000-strong People’s Climate March in New York on September 21 as the U.N. Climate Summit held in Manhattan. AgitArte’s transnational support network also led to the collective’s co-editing of the book When We Fight, We Win! (2016) a collection of richly illustrated stories of intersectional resistance from around the globe. The book’s release was followed by a still-ongoing podcast which features contributions from Jorge and fellow AgitArte founder and board member Deymirie Hernández.

AgitArte’s latest transnational collaboration is the multimedia onstage performance On the Eve of Abolition, whose storyline is “set in the year 2047 in the transnational liberated lands of what used to be known as the U.S. and Mexico, after a movement of abolitionists have created the conditions to end the prison-industrial complex.” Funded by various grants and co-commissioned by prestigious Latinx arts organizations around the U.S., the play was first shown in Dallas, Texas, in the fall of 2022.

Ant’s Work

Despite the flurry of organizing activity that followed Hurricane María, the 2019 Puerto Rican Uprising caught Jorge, Javi, and Su by surprise, as it did most informed observers. Jorge was not in Puerto Rico when it began; Javier left on a long-planned vacation with his partner the day before Rosselló finally announced his resignation, not without first participating with Papel Machete at the larger marches, while also attending the more combative demonstrations taking place at the governor’s mansion each night, because in his words “I can’t miss out on this!”

Su’s narrative of her experiences and impressions vividly illustrate the affective charge of that process.

I was impressed. Especially… we, since we have so many years going to marches and protests… there are certain ways that we’re used to: formations, blocs… and suddenly you see this wave of people, so that we could barely hold our contingent, our formation. Which to us is important, because it’s part of how the march looks… The thing is I see this groundswell of people, boom, boom, passing on all sides… motorcycles, horses… I really had never seen, lived, anything like it. I think the nights were also… it was a lot of intensity, a lot of adrenaline, a lot of emotion. And joy, also . . . To stop and look around, and say “Holy shit, this is happening! […] What I remember is that… and the huge solidarity between everyone participating. How folks took care of one another, the support amongst the groups… and to recognize ourselves within that reality as well. It’s something that I take with me.

“We worked a lot, too,” she notes, “generating visual material for the streets again” and participating in various “politico-cultural” performances during demonstrations.

The intensity subsided as soon as the governor announced his resignation, and for reasons that are beyond the scope of this essay, continued mobilization around a wide range of issues has not (yet) cohered into a sustained challenge to the colony’s political and economic status quo. Nonetheless, as Su eloquently puts it,

[E]ven though things took the direction they did, I think the work we did at that moment [following Hurricane María] opened the way towards everything that came after, up to the summer of 2019. You know, to take down a governor… I told myself, “This doesn’t come out of nowhere!” [“sacar a un gobernador… Yo me dije, ¡Esto no sale de la nada!”] All of this is [the product of] work that has been generated for many years, with our crews and our communities, and all of the work that was done after María . . . I understand it as a process that, even if it didn’t reach the place I imagined, that I wanted it to reach, did open up a world of possibilities, of having other systems of governance.

Whatever the emergent qualities expressed by the Uprising, it is also a product of the patient, molecular politico-affective work of AgitArte and other groups—what Javi calls “trabajo de hormiga” (“ants’ work”).

Jorge also insists on the importance of this work over the years. Looking back on my transcripts, I can’t help conclude that this notion of generative work is what actually defines his “proyecto de crisis:” “The crisis,” he says, just a few lines after an extended assessment of historical defeat, “truly gives you perspective to say: ‘The work is here. Let’s do it!”

José A. Laguarta Ramírez is a Research Associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (CENTRO) at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY). He has taught throughout the CUNY system and at the University of Puerto Rico, and is currently developing a book project on radical social movements, memory, and political affect in Puerto Rico from 1996 to the present.