The Shadow Side: Coco Fusco and the Censored Word

The monograph for Coco Fusco: Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island (2023), the artist’s recent retrospective at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, features illustrations from a series of videos reflecting on the censorship of poets in postrevolutionary Cuba: La confesión (The Confession, 2015), La botella al mar de María Elena (The Message in a Bottle from María Elena, 2015), Vivir en junio con la lengua afuera (To Live in June with Your Tongue Hanging Out, 2018), La sombra de Heberto Padilla (Padilla’s Shadow, 2021), and La Noche Eterna (The Eternal Night, 2022).

Each of these videos reverberates with the long echo of Fidel Castro’s 1961 “Words to Intellectuals” speech, which mandated, “Within the revolution, everything; outside the revolution, nothing.” They feature haunting imagery, literal and metaphoric, of poets having to eat their own words. Consider the case of poet María Elena Varela Cruz, who coauthored a dissident manifesto in 1991. An agent of the state forced her to swallow pieces of paper with her writing in front of her daughter. “May her mouth bleed,” they said before dragging her into the street.

Though just one facet of Fusco’s oeuvre across performance, video, and archival practices, these works elucidate the Cuban-American artist’s career-long ties to intellectuals on the island. Born in New York City in 1960, Coco Fusco first visited Cuba with her mother as an infant but would not return until the early 1980s. During a relatively brief period of increased exchange between leftist Cuban exiles and the Cuban state, she met a group of young experimental Cuban artists Ana Mendieta invited to the United States. During her subsequent visits to the island, Fusco witnessed how the relatively open art scene of the 1980s became unrecognizable following the loss of Soviet subsidies in the early 1990s. For nearly four decades, she has maintained close ties to artists on the island, returning often to collaborate on both research and creative projects, though the Cuban government has barred her from entry since 2018.

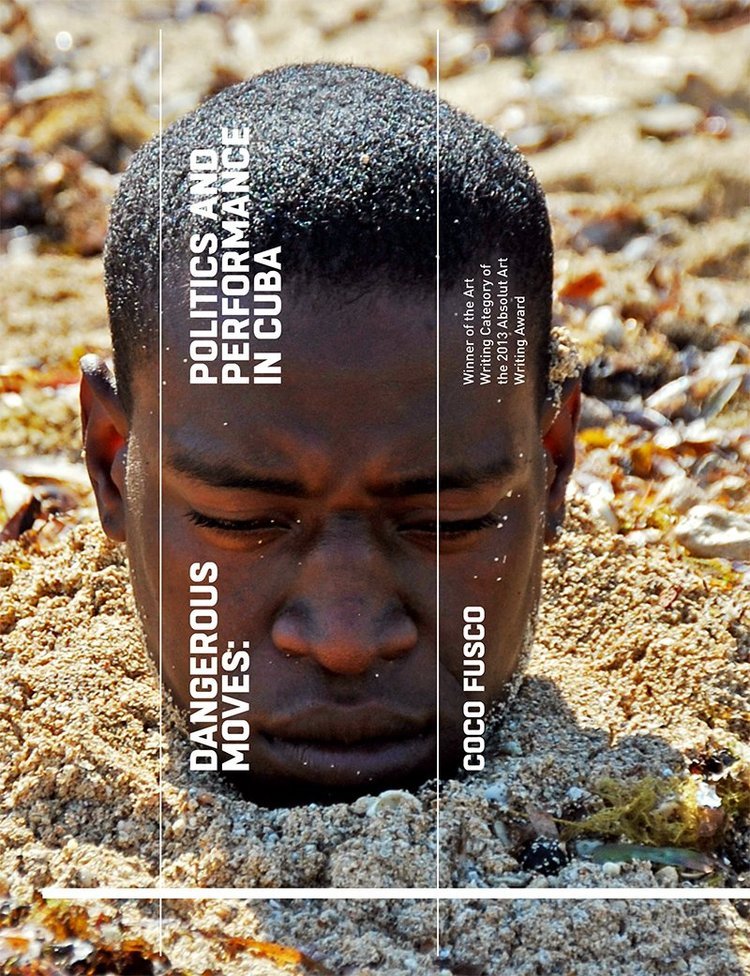

Fusco’s critiques of the role of the Cuban state in promoting certain artists while censoring others are unparalleled in their nuance. She has consistently acknowledged the importance of the arts and high quality of arts education in postrevolutionary Cuba, while at the same time demonstrating the intersections of a global art market hungry for exotic objects and a post-Soviet Cuban state desperate for currency. Her 2015 book, Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba, explores how Cuban artists, since the 1980s, have turned to performance to test political boundaries both inside and outside state structures and schools.

“ Fusco’s critiques of the role of the Cuban state in promoting certain artists while censoring others are unparalleled in their nuance.”

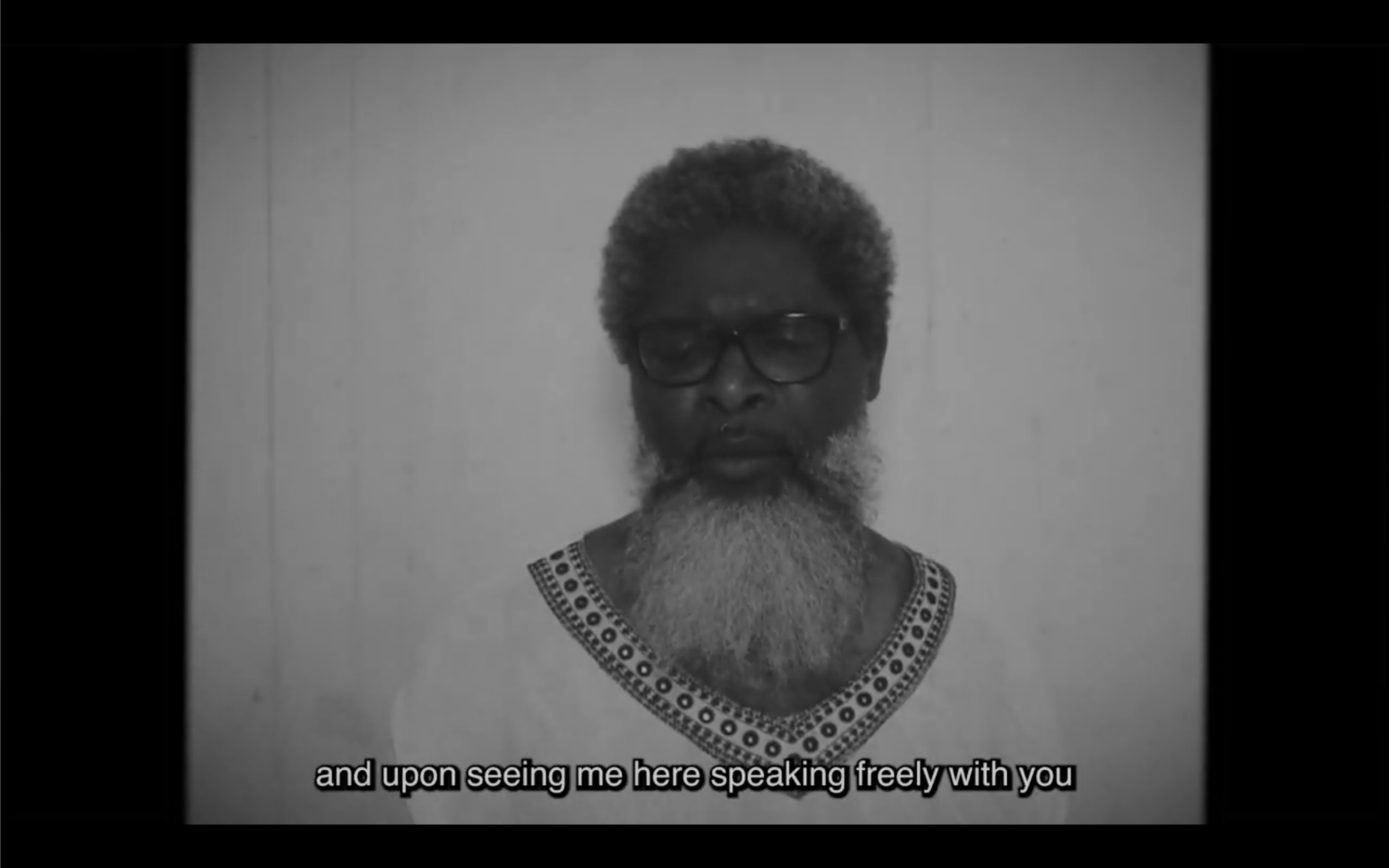

Fifty years later, Padilla’s Shadow engages the legacy of Cuban poet Heberto Padilla’s notorious April 1971 “confession.” Staged as a virtual reading on April 27, 2021, the performance—directed by Fusco—involved the collaboration of 20 Cuban artists and writers (living on and off the island) voicing Padilla’s profession to counterrevolutionary activity. Composed of individual recordings (so that those based in Cuba could prerecord and send their contributions by encrypted messaging to bypass state censorship), the collective performance was available via social media and streamed on the websites of five art institutions.

Presented as “a commemorative act,” Padilla’s Shadow urges its audience to reconsider their own relationship to the Cuban Revolution and artistic dissent on the island. Filmed in black and white, the video imitates the look of a Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) newsreel, with flickering effects and at times grainy footage. Yet opening credits claim Movimiento San Isidro (MSI) and 27N—contemporary social movements on the island formed in response to artistic censorship—produced the video. In conjunction with the title, this framing suggests that artists and writers on the island today continue to live under the shadow cast by Padilla’s trial.

At the time, Padilla’s belated arrest and imprisonment for writing Fuera del juego (Out of the Game)—a book of poetry awarded a major national literary prize in 1968—were widely condemned by progressive writers, such as Julio Cortázar, Susan Sontag, and Jean-Paul Sartre, many of whom subsequently abandoned their support for the Cuban Revolution. Officials forced Padilla to perform an act of auto-critique before the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), admitting to betraying the Revolution through self-interested expression (i.e., cynical poetry and gossip).

Rewatching Padilla’s Shadow, which runs nearly three hours and is in Spanish with English subtitles, I am aware that each of these Cuban participants is or has been a target of the Cuban state’s silencing apparatus. Many now live in exile abroad, including several who resided in Havana at the time of recording but have since been forced to leave. Each of them has refused to stay quiet, which is why watching them take on Padilla’s coerced words is unsettling. It is as if more than just casting a shadow, Padilla’s confession forecasted these actors. Time begins to move in multiple directions.

The performers voice the drawn-out confession in succession, each speaking for approximately five to 10 minutes. Some read their words; others appear to have memorized them. Regardless, as performer after performer attests to speaking openly and spontaneously of their free will, the more heavily rehearsed and forced the statement appears. This stiltedness is a reminder of how performance casts its own shadows, evading censors through its repetitions. Speaking as if pursued by one’s own shadow, in this case, Padilla’s resuscitated words, signal other than they denote. This play between connotation and denotation is itself the material of poets. Thus, the ritual of penance, which circles around and around back to the same admissions of bitterness, gives life, in its own strange form, to the progressive myth of the Revolution.

Significantly, one of the main charges UNEAC leveled against Padilla’s poetry, allegedly proving its counterrevolutionary intent, was his concept of “time as a recurring and repeating circle instead of an ascending line.” Yet the farce of the confession itself is circular, not only in the moment of its original utterance but also in the context of its 2021 reperformance. Padilla’s words are exemplary of how the postrevolutionary Cuban state has compelled its citizenry to voice a socialist morality that leaves no room for doubt or despair and has subsumed artistic practices to this agenda.

Critics of Decree 349, a controversial censorship law that went into effect on the island in late 2018, compare the current moment to El Quinquenio gris or Five Grey Years, an era of heightened cultural repression, inaugurated by the Padilla Affair. Announced shortly after Miguel Díaz-Canel assumed the Cuban presidency in 2018, Decree 349 coincided with the repression of the #00 Bienal de la Habana that artists organized independent of the state’s cultural ministries.

“Perhaps more than any other figure in the diaspora, Fusco has kept the lives and works of these artists visible before the international arts community. ”

Inspired by Fusco’s Dangerous Moves, I visited the island in late 2017 to participate in Poesía Sin Fin, an independent poetry festival, at which I first heard about the #00 Bienal. Fusco had seen me post on Facebook about my trip to Havana and warned me to not bring any paper materials related to the #00 Bienal, as she had just been turned back by Cuban officials upon arriving at José Martí airport. As Coco predicted, customs briefly detained me, interrogated me about my plans, and searched my belongings; however, they allowed me entry.

During more than a dozen research and family trips to Havana between 2017 and 2022, I met several artists featured in Padilla’s Shadow, as well as others who are either currently serving prison terms for participation in peaceful protests or living in the United States, Mexico, Spain, and other European countries in exile. Perhaps more than any other figure in the diaspora, Fusco has kept the lives and works of these artists visible before the international arts community, as well as linked them to human rights organizations. She has done so often behind the scenes and at the cost of access to the island.

The daughter of a Cuban exile, I had been writing poems about my father’s impossible-to-know homeland for years when I learned of Fusco’s performances in Cuba. In my book Precarious Forms: Performing Utopia in the Neoliberal Americas (2020), I examine two performances Fusco collaborated with Cuban artist and curator Sandra Ceballos to stage. (Ceballos, who maintains an independent gallery in Havana, is one of the readers of Padilla’s confession in Fusco’s 2021 video.) In these clandestine performances, staged parallel to the official Havana Biennials, Fusco gives concrete form to exilic pain. Her face is in the shadows, her body underground or laid out like a corpse. But there are words, written while buried alive, or at the entry to the wake. Not quite poems, they repeat and resonate through space and time, seeking new mouths, eyes, and ears.

Candice Amich is an Associate Professor of English at Vanderbilt University. She is the author of Precarious Forms: Performing Utopia in the Neoliberal Americas (Northwestern University Press, 2020) and co-editor, with Elin Diamond and Denise Varney, of Performance, Feminism and Affect in Neoliberal Times (Palgrave, 2017). She is currently at work on “Planetary Cuba: Post-Soviet Performances of Utopia, 1991-present,” which examines the rise of an oppositional performance culture in response to the island’s neoliberal transformation.