Art as Political Education: A Conversation with Nitza Tufiño

In celebration of their 50th anniversary, “Taller Boricua: A Political Print Shop in New York” opened at El Museo del Barrio last September. It is the first time that a major institution has exhibited this important body of work produced by what is commonly known as ‘The Puerto Rican Workshop.’

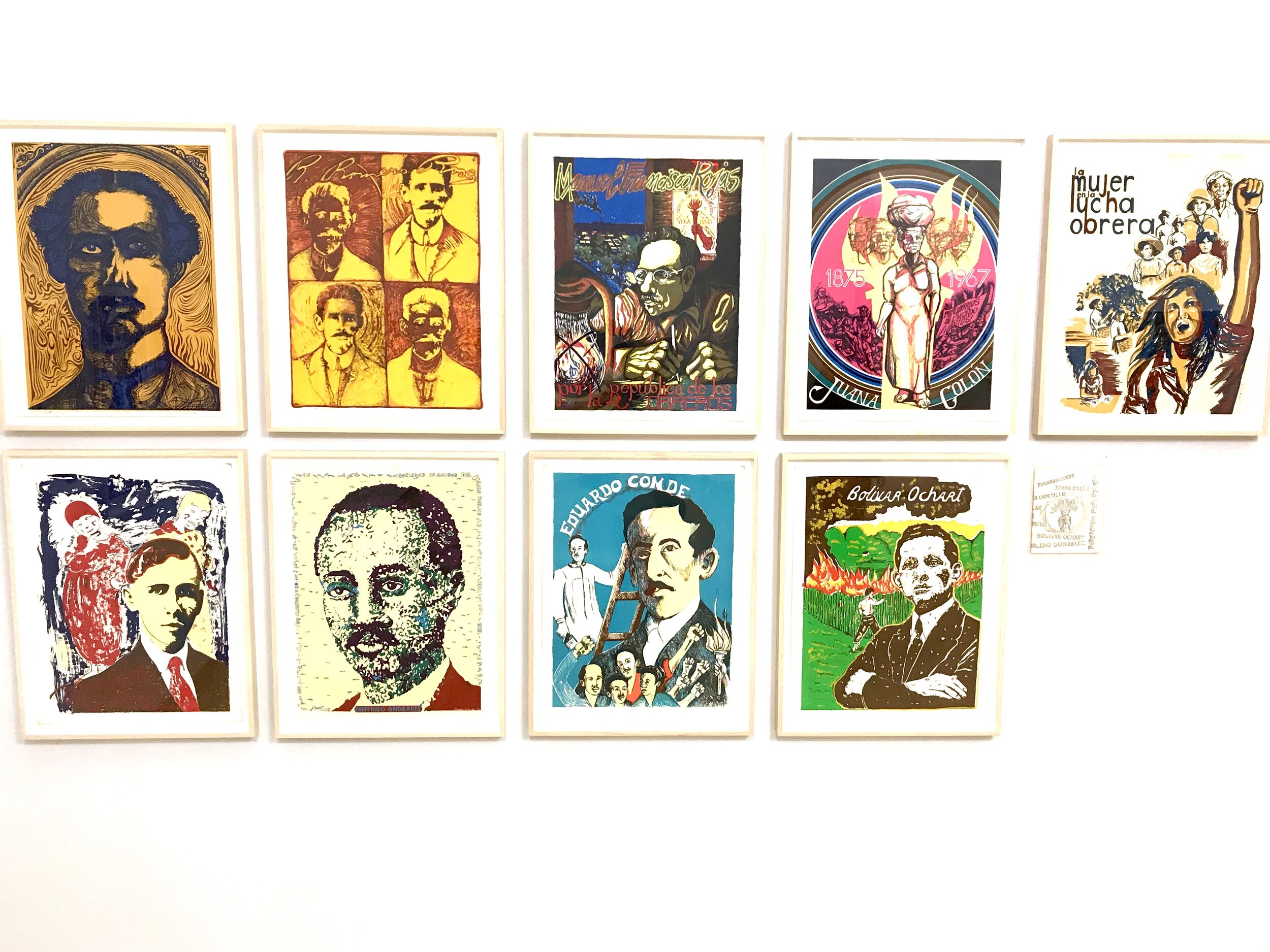

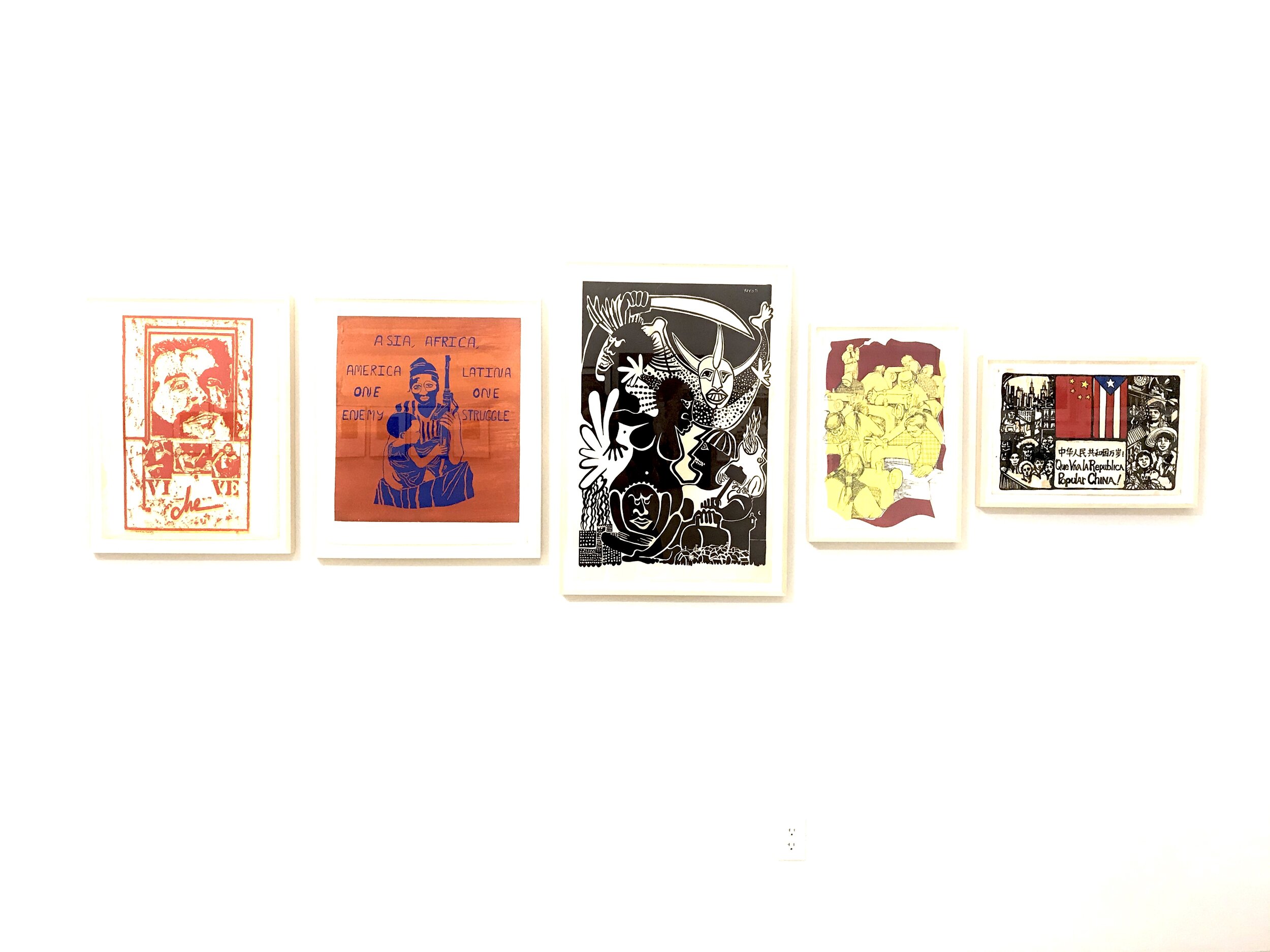

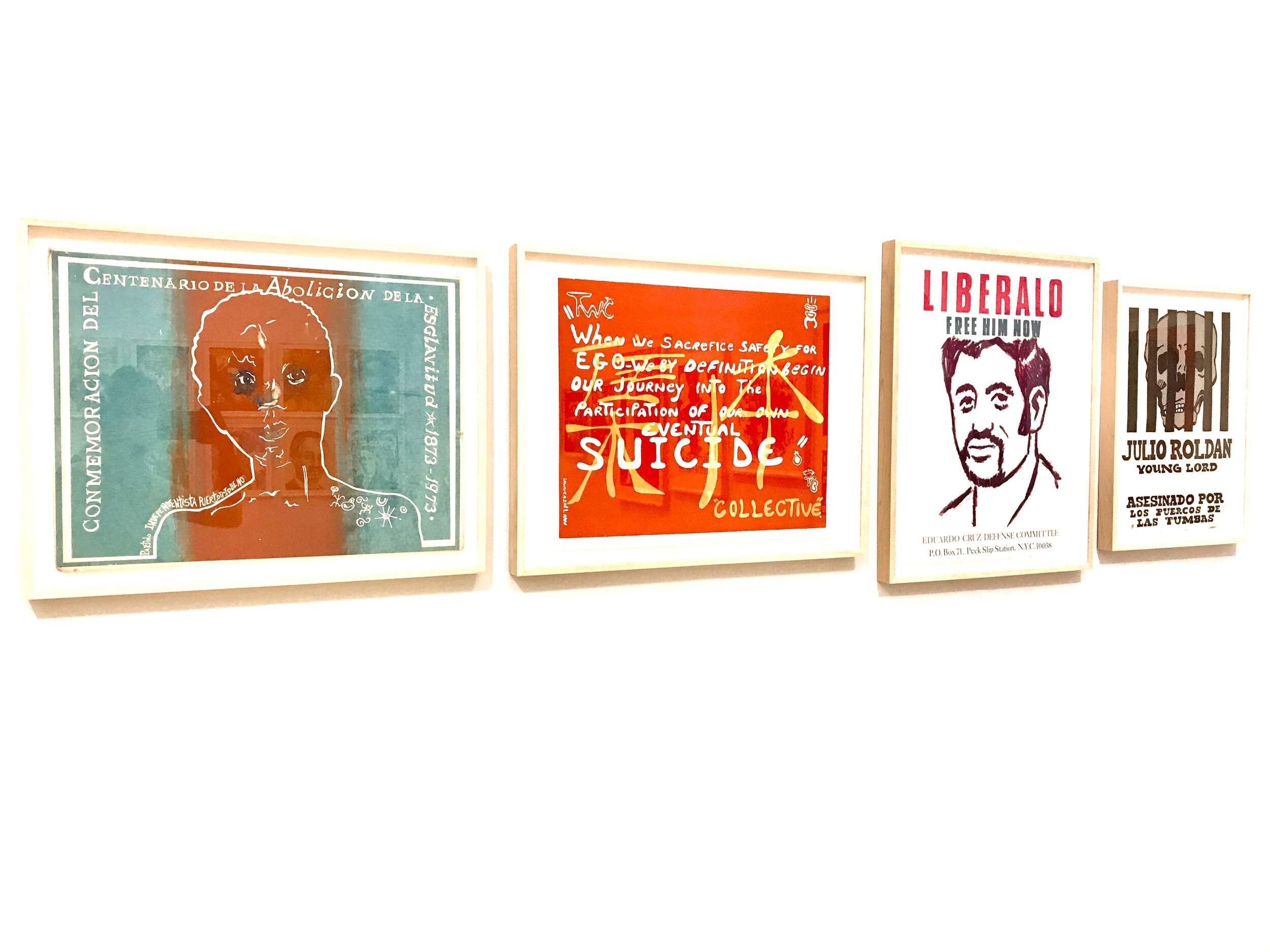

The exhibition, which comprises more than 200 works and ephemera—including serigraphs, lithographs, linocuts, paintings, assemblages, collages, and drawing prints—displays works mainly produced in the 1970s by founding and early members Marcos Dimas, Carlos Osorio (1927-1984), Jorge Soto Sánchez (1947-1987), Rafael Tufiño (1922-2008), and Nitza Tufiño, among several others. The themes of these works center on issues of Puerto Rican independence, international workers’ solidarity, and anti-imperialist movements in New York City, the Caribbean and Latin America. The museum announced an online version of the exhibition, which is now available due to the current challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nitza Tufiño, one of the founders, was instrumental in organizing this retrospective. Born in Mexico City in 1949, she grew up in Puerto Rico and learned graphic arts early in her childhood while working with her late father, the painter and printmaker Rafael Tufiño. After earning a B.F.A. from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Tufiño moved to New York City, where along with a group of artists, educators and activists, she helped establish El Museo del Barrio.

Art As Activism

Tufiño describes the early years of Taller Boricua as a time of experimentation, merging historical, artistic, and educational themes. In the beginning, the workshop was a place for younger artists to meet one another, mostly Puerto Ricans in New York City, and work alongside recognized print makers and artists like Rafael Tufiño.

In the words of Tufiño, she along with others “formed our museum, we said, ‘let's do our own institution.’ Other Latin Americans probably don’t do it because they have their consulates, they have their embassies. We are more political in that sense because we don't have nothing like that.”

Tufiño recalls obtaining a highly sought commission to create one of her signature ceramic murals at the 103rd St. and Lexington Avenue subway station in East Harlem, where she managed to incorporate Taino symbols,” she said of her individual activism. “I never told the architect that those were Taino symbols. I never said what I knew for myself as an artist—this is a cave. In Puerto Rico, there are many caves. The Indians hid objects in caves because they didn’t want the Spaniards to find them...the cemis and other objects. It was a magical Island. Because you had the tropics, you had the fruits and the flowers—and then I incorporated the final symbols, on both sides of the station. I had very little money to do that. It was not like I had more money, so I could do the whole station. I was one of the first [artists doing this type of work]. But I was able to convince them because they were beautiful, they were abstract, they were colorful, and they agreed to it. They didn’t know then what Neo-Borinquen was, that the island of Puerto Rico is called Borinquen. And that was the name that the Indians gave to the island, right? Now I call it Neo-Boriken. Why? Because it is the new Borinquen, on 103rd Street.”

Resignifying public space and creating new institutions gave strength to the movements and collectives that clamored to improve the living conditions of our communities. The symbolic, clinging to memory, allows us to make sense of lived experiences, affect, and aesthetics. “And that's how you do political work,'' Tufiño added. “You understand that later on. That it can transcend. Because what you want is to transcend. And for people to look for more information. ‘What is this? What does it mean?’ A lot of people don't know, but our people, they look at it and they go, ‘Wow!’”

Tufiño took a similar approach when she completed a mural at the Third Street Music School: “So I said, ‘Okay, I'm gonna have all the time [signatures], [notation] symbols, and play with different instruments.’ That's how you do political work. That’s on the Lower East Side, so when a Puerto Rican or a young person looks at that, and has seen some of those things, they know, ‘That's me! That’s a pre-Columbian symbol.’” The mural, in essence, captures the energy and rhythms of the surrounding neighborhood, known alternatively as Loisaida. Its symbolism is a vessel for memory and the remembrance of a homeland.

A Political Education

To this day, the work of Taller Boricua regularly uplifts histories of resistance that have been erased from the official history of Puerto Rico. When the collective first started picking topics for artwork, representation was pivotal. “We started brainstorming and...decided we should start from the beginning.” Eventually, the collective produced an annual portfolio series on Puerto Rican patriots, an idea suggested by one of the founding members, Manuel Otero. According to Tufiño, “[the series] was very important for people to look at it, and to also see themselves.”

Tufiño also played an integral role in establishing the education department at Taller Boricua. She taught classes and brought artists to host workshops for the youth, involving children into the creation of artwork where they could see themselves and pursue an active political dialogue. Tufiño added that, “[Taller Boricua] is a sanctuary for us. You want to be part of it? You're welcome. But you have to understand ‘que aquí se habla de todo.’ If you don't like it, we can discuss it and all that, but you cannot stop anybody. So it's an open space. And it has to be that way.”

In the spirit of experimentation and incorporating elements of culture and memory, Tufiño used techniques that go beyond traditional aesthetic forms and reflect her political work. There are some of the drawings and works at the show that were done “on a steel screen with sewing. [while experimenting and creating] I felt scared, because I'm not really an artist, I'm more of an activist in action,” she stated. Ultimately, Tufiño suggests embracing one’s culture, history, and community can also be a reflective act, with questions like, “Why is this meaningful [or] meaningless? Does it signify anything?”

Deconstruction has held a particular place in her artistic journey as a necessary practice in terms of activism for social transformation. Tufiño asserts there is much rooted in the colonial mentality: “Even though you're here, you feel you're not connected, there's a lot of stuff that you're still hindered by because of colonialism. Decolonizing, looking back in history [...] we were doing it. It wasn't called that, but we were doing it back then and now they're doing it and calling it something else.”

Taller Boricua continues to serve as a focal point for the affirmation of identity. Their body of work connects artistic production in the diaspora to the homeland and uplifts non-Western art history narratives. While this exhibition is focused on its first decade of existence, it also looks at the close relationship between Taller Boricua and El Museo del Barrio, examining their common members, ethos, and the artist’s role in the creation of a visual identity for the museum’s programs and exhibitions in its early years.

As a cultural advocate and artist who has long worked in the community and within the collective, Tufiño insisted that art, as political education, is “about identity, about creating things that have to do with identification, where people could see themselves within symbols. It is how we get translated in history, [art being a way of communicating] the subconscious and the conscious mind—all of that. We need to be aware of it […] and to organize.”

“Taller Boricua: A Political Print Shop” will be on display at El Museo del Barrio in New York City until January 17, 2021. The online version of the exhibition can be accessed by visiting tallerboricua-elmuseo.org

All images courtesy of author.

Nitza Tufiño is a renowned Nuyorican artist based in New York City, an advocate of culture in El Barrio for decades. Her career has led her to work with great masters of Puerto Rican, Mexican and Latin American graphics.Tufiño’s commitment to public art led her to be recognized as El Taller Boricua’s first female artist in 1970, and has been involved with El Taller since that time. Nitza is also a member of “El Consejo Grafico”, a national coalition of Latino printmaking workshops and individual printmakers. Tufiño has been the recipient of many awards throughout her four decades as an artist that include: the Donald G. Sullivan Award from the Department of Urban Planning, Hunter College; the Mid-Atlantic Endowment for the Arts Regional Award, from the Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation; the New York’s Foundation for the Arts Artist Fellowship; the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund for Outstanding Contribution to the Arts Award in conjunction with Mayor David Dinkins of New York; New York City Council’s “Excellence in Arts” Award given by Council President, Andrew Stein and the Manhattan Borough President’s Excellence and Outstanding Achievement Award given by Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger, among others.

Diana Ramos Gutiérrez is a culture and human rights advocate based in Vieques, Puerto Rico. As a cultural journalist, social media specialist, photographer and arts administrator, Ramos-Gutiérrez collaborates with independent media in Latin America and Radio Vieques, a community radio station. She is also part of the advisory board of the Vieques Historical Archive, a community-based organization that builds participation around historical materials and Viequense cultural heritage. There, she develops educational programs. She is also director of the Vieques Film and Human Rights Festival.