A Region in the Mind, Terrenos y Cuentos: G. Rosa Rey in Conversation with Natalia Lassalle-Morillo

G. Rosa-Rey is a Brooklyn, N.Y. based visual artist. Her work invokes texture, gestural markings and grids to reference place. She incises and probes the canvas, creating “terrenos”—topographies and geographies that evoke fragmentation and non-linearity—meeting places for memory and history to overlap. Conceptually, Rosa’s use of materials are informed by the Puerto Rican diasporic consciousness in the wake of Operation Bootstrap, and guided by her experiences growing up and living in the United States.

Born in Isabela, Puerto Rico, Rosa-Rey and her family moved to Hartford, Connecticut in the late 1950s during the Puerto Rican migration to the States. In the early 1970s she relocated to New York City to study fine art as an undergraduate at Pratt Institute, and continued her graduate studies in the same field at Columbia University. Rosa-Rey's creative pursuits expanded to include flamenco dance. She returned to her painting practice, feeling that she had developed a sense of clarity regarding personal history and political events that informed her trajectory.

In the light of her first solo show at Hidrante this February, Natalia Lassalle-Morillo and G. Rosa Rey spoke over Zoom on a Monday evening, nestled by the cacophony of sirens in Hato Rey, Puerto Rico, and Flatbush, Brooklyn.

—

Natalia: I want to start out by asking you a question that is quite personal, but that I feel defines your work. What is home for you?

G. Rosa-Rey: Where do I belong? That's a big question for me. And perhaps home was Puerto Rico. This was my first home up until the age of four. My family left Puerto Rico during the Puerto Rican Great Migration, in 1959. And as evident in that family photo you have seen, which was taken at the airport in Puerto Rico, our expressions upon leaving foreshadows this foreboding future. So my sense of home was not one place. When we came to the States, we were constantly moving. And that's what I remember.

Natalia: I want to talk about the title of this body of work. First, let’s start with a Region in the Mind. I’m curious about what this phrase means to you, and how it connects to the works that will be exhibited at Hidrante this upcoming February.

G. Rosa-Rey: Region in the mind has its origins in history, lived experiences and memory for me. It derives from James Baldwin's essay, “Letter From a Region in my Mind”, where Baldwin draws from personal and systemic experience to examine himself and to also examine the power structure in this country. And so I use the title Region in the Mind, which is slightly different, as a metaphor for an internal pulsation of knowing and reckoning with these forces that I had to live with all my life.

Natalia: When I last visited your studio, you said: “Memory is a region in the mind”. You refer to it as a region in the mind, and I refer to this as a consciousness in the atmosphere—one that results from the sense of displacement that you, me, and many other Puerto Ricans have experienced at some point of our lives. The experience that you gather outside of the motherland can disconnect you from the visceral experience of being in Puerto Rico. There’s so much nuance I’ve had to reconnect with since I returned. Nuance that is intangible. Nuance that I can’t really put words to, but that is very much embedded in the fiber of being here. You feel such a powerful connection to this place and simultaneously feel such lack of control over our destiny. We haven’t processed the colonial history we have inherited, nor the accumulation of tragedies that have taken place in the last 10 years… I've come to understand that what we want, we must imagine and create, because it doesn't exist yet.

G. Rosa Rey: But I have also wondered: have we had the time to mourn? I think that many of us have been so preoccupied with survival, that we have not mourned. We have not had that space to mourn, because mourning entails vulnerability and it's important to stay strong, and to be able to do, really just to survive. I feel like I am just now mourning, and I have to get through this mourning before I can get to that next stage, which is imagining another place. And often when I do think about imagining another place, I sometimes think of inhabiting the margins because it's also a form of delinking, of saying to myself:” I'm getting out of this, and I am not a part of this kind of value system. I want something completely different. Let me explore what these margins really are”.

Natalia: It’s beautiful that you say this… through my work I’ve been facilitating spaces of dialogue, which have really become spaces of grief and mourning. I think we're moving at a pace where language doesn't do service to the nuance of our feelings. So it becomes necessary to summon spaces where we can spend time and commune with each other, in order to channel this grief into something transformative.

G. Rosa Rey: Sometimes we are thought of as people who don’t have feelings. For me, there has been a tremendous breakthrough. I see myself truly mourning and crying and I feel how incredible it is to get to the point where I can allow myself to feel those emotions, to see all that history through. Because I think you have to go through that in order to arrive at the next step. To acknowledge these emotions, pay attention to them, and begin the next journey.

Natalia: I’ve gathered from our many conversations how childhood memories resurface in your work. One of these memories is forever embedded in my mind… a dream where your house in Connecticut would flood entirely with water. What is your relationship to memory and history?

G. Rosa Rey: The house filling up with water and being able to swim in it—I’m honestly not sure if this was a dream or just recurring thoughts that came out during play. It's sort of a blur, but this took place in Hartford. And Hartford is very important to me because my mother's death took place there, so it’s a very sacred place for me. This was also where my early memories were formed. But the image of the house filling with water was related to the womb, and this wanting to return to origins. I'm not sure if I was longing to go back to Puerto Rico or a place of safety.

But in terms of the materials and the process, these references do go back to childhood. I come from a fairly large family of many siblings. There were so many of us that we couldn't be in the house, so we were always outside. And so the outdoors became my playground. I played with the earth. I drew on it, and excavated the ground with the branches. A memory that stands out is scraping what I thought was silver off the rocks and transferring that dust by allowing the residue to fall into these penny paper bags that I had collected. They almost became these samples, like containers for whatever that excavation was that I was doing. And so today I find those memories resurfacing in the work. They are innocent moments of, I would say, investigation and discovery for me. I have also incorporated some of those processes in my current work.

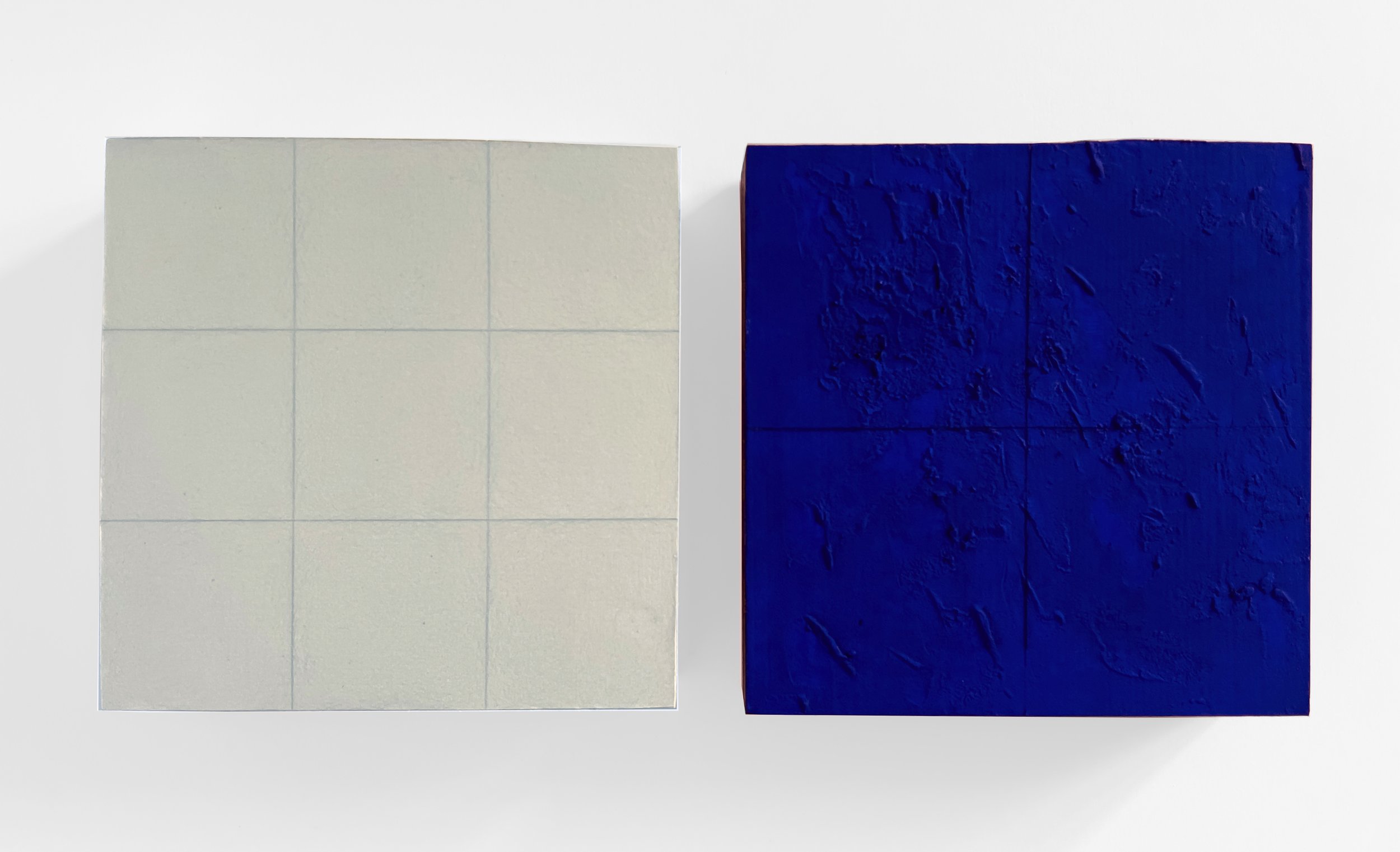

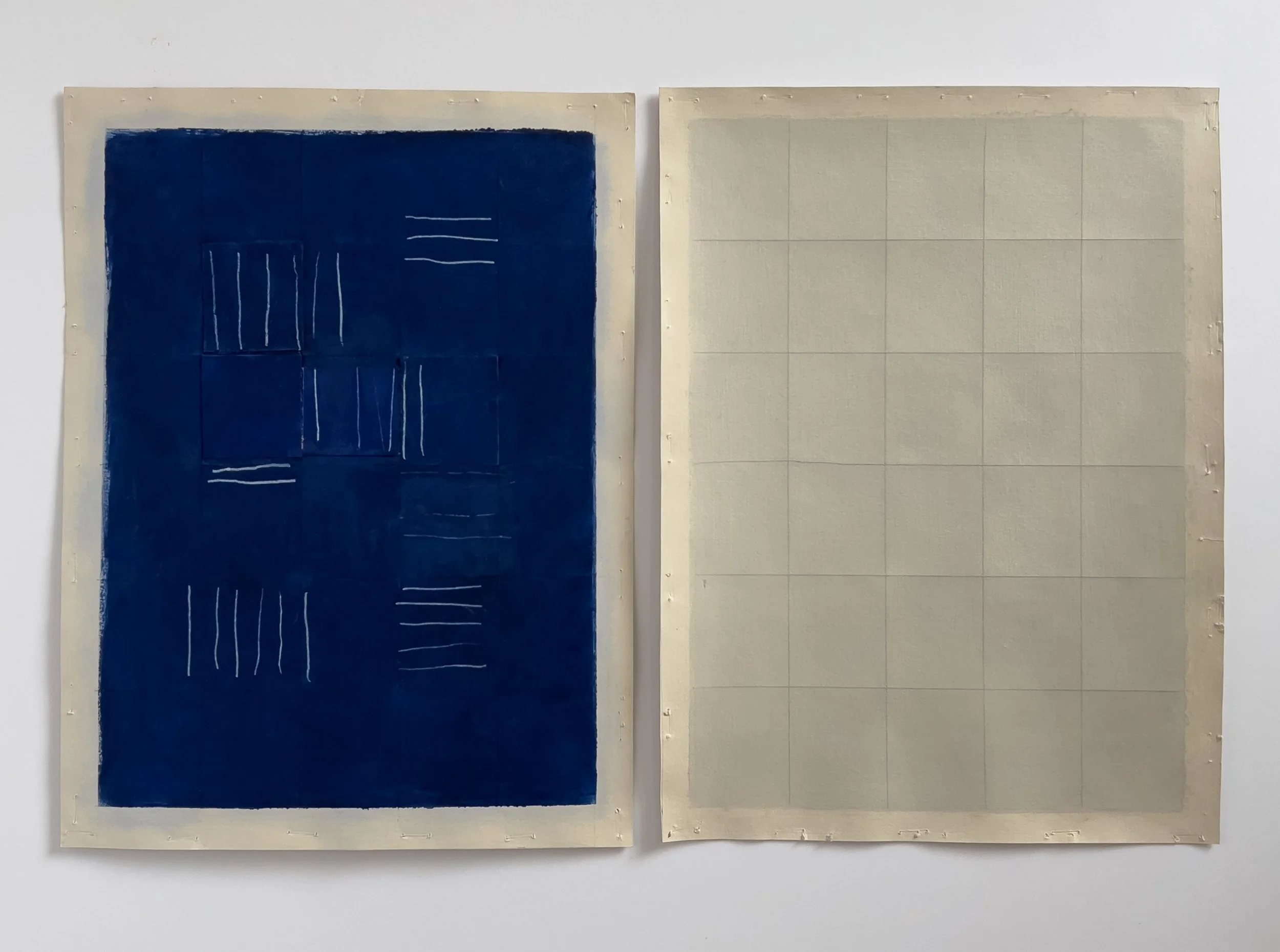

Natalia: Your paintings are full of textures. They are terrains, and they look like topographies and geographies. I’m curious to ask you about the colors, materials and tools you use, for example sand and archeological tools, since they allude to “territory” in a particular way.

G. Rosa Rey: Many of the materials and processes also go back to childhood. These pieces have a lot to do with earth. I use brushes, excavation tools such as spatulas, dental picks, magnifying glasses, measuring tapes, and branches, which I have sharpened and shaped to further scratch marks and probe the surfaces that I work on. I also use sand, which I transfer from sandpaper onto the surfaces that I'm working on. The work is never complete. But eventually these images float on the wall, evoking movement and shifting for me…unanchored terrains, which I feel are a reference to the diaspora. They're just floating, not anchored in any form.

The images represent internal terrains I would say of consciousness, like a place where history and memory intersect and inform who we are, the pulse of who we are. And those things can come together in very pleasant ways or in very unpleasant ways.

Natalia: Can you talk about the second part of the title, Terrenos y Cuentos?

G. Rosa Rey: I think that the work is informed by a multitude of sources, the most prominent being historical sources, memory and story. And they're the stories that we create to give meaning, and also to build community. Memory is always very slippery because it’s very difficult to grasp time. So when I'm thinking of these stories, I'm taken back to my mom, my beloved mom, who used to tell oral stories. The stories that she told were about el cuco, or la mano arrugada. She would tell stories to give us advice. For instance, one that I remember was: be careful not to swallow an avocado seed because you will grow an avocado tree on your head. These stories were moments of family union. And honestly, it was also a way to connect back to Puerto Rico.

Natalia: El cuco made it to my generation. My grandma was all about el cuco.

G. Rosa Rey: I was terrified of el cuco.

Natalia: But I think this relates to mythmaking, and our necessity to create myths to find a language or meaning for this strange experience of belonging.

Throughout my time knowing you, you’ve referenced different sensorial images and aural phenomena in relation to the diasporic experience. A couple of months ago, you mentioned how throughout your life, you heard this ever-present hum that continuously reminded you that you were from many places, and had many parts. How does being a Puerto Rican from the diaspora, and your current relationship to your birthplace, manifest in your work?

G. Rosa Rey: I'm really excited to share my work in my place of origin. And it continues to have a deep meaning for me, even though I've been gone for so long. I have family there. The house that I was born in is still there. La finca that my mother owned is still there and we still own that land.

There's always this sadness when I go. It’s hard to pinpoint why. It’s like something is gone, something that I wish I had. I’m not quite sure what it is, and I can make up a lot of justifications for this melancholiness. It’s very deep and related to something lost, and one can’t capture that. Knowing how changed we’ve become. We’re not who we were back then, and neither is the place. The place has changed. I think I need to spend some time in Puerto Rico to investigate and discover what these emotions are.

Natalia: I agree. Every time I return, the first week is one of chaos and adjustment. When people used to ask me what was special about this place, I would speak about how strong the gravitational pull was here. Then I started reading about the Puerto Rico trench, which is the deepest point in the Atlantic Ocean, and the point with the most negative gravity anomaly on earth. This is my way of justifying the unjustifiable.

This is an experience we both share. Perhaps a way of beginning this journey of return is your work spending time here. I'm excited for it to live here and have an encounter with the birth land.

G. Rosa Rey: Yes, it's almost like they (the pieces) are leaving. They're cocooned, and they're going out and they're being shared. That’s what it’s all about really, the work being out there and the viewer interacting with it. And what a better place than Puerto Rico. I would have never thought that the work would ever even go there. So that too is something that I'm trying to process, it’s a big deal. It's almost like going full circle, but not quite.

I think if the work comes back that it will, for lack of a better word, return maybe blessed by something.

Natalia: I wanted to ask you about a quote you mentioned when I last visited your studio. “The political is in there because I put it in there. It’s in there because I cut it in with a blade.” This stayed with me for weeks. It also reminded me of what’s so powerful about abstraction—it can behave like a poem, and the meaning is embedded within it.

You made this comment in relation to your use of the grid, and your conflicting relationship to it: the grid helps you envision space, but you are also aware of how this same envisioning of space was both a tool and a product of colonization. We exist at a time where we are facing a collapse of modernity and its grids. This is very visible in a place like Puerto Rico—a country of failed electrical grids. It’s a long preface to this question, but I wanted to unpack your relationship to the grid and its significance in this body of work.

G. Rosa Rey: “The political is in the work. I know it's in there, because I put it in there.” That was Jack Whitten who said that, and it really stuck with me.

My process often involves drawing the grid with an X-ACTO blade, actually. And so the lines appear as surface markings, but they are incisions. That's what I call them, because they cut through the surface, but not through the paper. It's also an extension of that hum, something which continues to need reckoning with. These incisions are an awareness for me of the grid as a colonial device that partitioned land and set up borders. Of forced removal, which took place not only here, but in other countries as well, and which continues to take place.

Natalia: I am always collecting sensorial “imagery”, whether it’s images, sounds or dreams. Dreams are very important for me, because I’m always trusting the space the subconscious mind occupies. I feel dreams speak to what I am not manifesting in my waking life. What is your relationship to dreams?

G. Rosa Rey: Dreams are always very complex. And I think what makes them complex is time. Because in dreams, everything seems to be displaced, and in many ways time doesn’t exist because the past is not there, the future is not here, and the now doesn’t exist because it is gone, right? When we say we live in the present, right after making that statement, the present is gone. Where is time? It’s very slippery. I find non-linear time fascinating, and I try to convey some of those ideas, stories, and that sense of displacement. You can take some of my pieces and arrange them any way you want because there is no order to them.

There’s something about that which is also connected to diaspora. Displacement, the concept of time, of memory, it just seems to fold into itself in dreams. It’s fascinating. Even the concept of time I’m still trying to understand, because everything is an illusion. I'm sure philosophers have tried to answer that question, but it's never fixed, because everything is constantly changing. Everything is so fluid.

Natalia: I’m interested in this which you bring up: non-linear time, diasporic time, and the fragmentation of memory that emerges from that. I sometimes refer to this as “the piling up of time”. Past, present, future happening at the same time.

G. Rosa Rey: Having all these lines moving in different directions, but happening at the same time.

Natalia: Exactly. Rosa, I also wanted to ask about where you gather your influences. I’m aware you were trained as an artist in institutions such as Pratt and Columbia, but I know that most of the work you are currently developing was created outside the margins of an institution. I also know you were a Flamenco dancer, which I have always been curious to ask about and intrigued to know if it has at all influenced your abstract work.

G. Rosa Rey: I must say that I am grateful that I did go through those institutions, though when I was there, I was the only Puerto Rican in my department at Columbia. It was a very Euro/Western-centric kind of place. Art considered to be outside that genre was referred to as “primitive.” So it was difficult because I had to do a lot of investigation on my own, and I think that some of that education is hard to get away from. It seeps into you and it’s hard to renounce it.

But I would say my early influence as far as painting goes was my professor and mentor at the Pratt Institute, Ernie Briggs. He was a second generation abstract expressionist. Art was personal and self-reflective for Briggs. He said that you have to communicate with yourself first and then you can communicate with your viewers. This stuck with me, that self-analysis and self-questioning.

Flamenco was also an influence in the work. I think that I had to leave painting and venture into something that was more supportive and that was not Eurocentric, like the education that I was getting. And so flamenco offered that. It was already a ready-made art form that I was able to enter and feel honestly like I was at home. Because flamenco is protest, it's passion and it's earth and all these qualities have seeped into the work. Those were experiences of love, not only teaching it, but also professionally dancing it.

I returned to the visual arts after Flamenco because I was able to re-enter the work with more consciousness of the self. I realized I’m still looking for something and I haven’t found it. I suppose this keeps me moving.

Natalia: I’m very happy you answered this question about flamenco, because it's something that I've always wondered about. I can see it in the work. Flamenco is earth, it’s beating into the earth.

G. Rosa Rey: It's all down. The plié is down into that ground, you know. And the politics are there already, so that attracted me to it. It’s like a protest. This is pariah, this is the cry. And I felt “this is where I belong, right here”.

Natalia: You spend a lot of time doing simple gestures that are very difficult, and that hold great depth and meaning. Can you share a bit about how your process of making these works unfolds, in and out of the studio?

G. Rosa Rey: All I can say is that those simple gestures and marks in my work are thought up as elemental or primordial. And it's a way to express ideas from the bare bones without having the seductive embellishments.

Natalia: It's raw. There's something else that is seeping through the surface that is not beautiful.

G. Rosa Rey: I think it goes a little deeper. Maybe into the abyss or something, or into those areas that are not the most comfortable in the world.

—

a region in the mind: terrenos y cuentos will be on view from at Hidrante in San Juan, Puerto Rico from February 16 to April 4, 2023.

Natalia Lassalle-Morillo (b. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico) is a visual artist, filmmaker, theater artist, performer and educator whose work reconstructs history through a transdisciplinary approach to research, form and narrative. Melding theatrical performance, intuitive experimental ethnography, and collaborations with non-professional performers, Natalia’s practice centers on excavating imagined and archived history, decentralizing canonical narratives through embodied reenactments, and challenging written history by foregrounding instead the creation of new mythologies. Her multi-channel films, performance works and multiplatform projects explore familial, neighborly and citizen relationships in the context of Caribbean colonial history, and the resulting imperialist oppression that has altered generations of families’ material and spiritual trajectories. Bringing the practice of theater into the camera, Natalia explores a methodology that creates its own decolonial rhythms.

She has been an artist fellow at the Smithsonian, and participated in residencies at Amant Foundation (NY), MassMoca (Massachusetts) , Fonderie Darling (Montreal), and Pioneer Works (NY, Upcoming). She has exhibited her work at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Museo Cabañas (Guadalajara, MX), TEA Espacio de las Artes en Tenerife (Canary Islands), SeMa (Korea), The Flaherty Seminar, the Walt Disney Modular Theatre in California, among other venues, festivals and performance venues internationally. She has taught interdisciplinary performance and film at Bard College, CalArts, and MICA.

Natalia was born in Puerto Rico, developing her practice nomadically between Puerto Rico, New York, Montréal, Miami, Los Angeles and Germany, but is currently based in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

G. Rosa-Rey (b. 1955, Isabela, PR) is a Brooklyn, N.Y.-based visual artist. She invokes texture, gestural markings, and grids to reference place. Conceptually, Rosa’s use of materials is informed by the Puerto Rican diasporic consciousness in the wake of Operation Bootstrap and guided by her experiences growing up and living in the United States. Born in Isabela, Puerto Rico, Rosa-Rey and her family moved to Hartford, Connecticut, in the late 1950s. In the early 1970s, she relocated to New York City to study fine art as an undergraduate at Pratt Institute. She continued her graduate studies in the same field at Columbia University, where her studies also included ceramics.