25 Years of La Gringa: An Interview with Carmen Rivera

25 years have passed since the opening of Carmen Rivera’s La Gringa, extending its reign as the longest running off-Broadway Spanish-language production in New York City. “It still doesn’t feel real,” says Rivera. “I never thought it would go past the year, and to be here, 25 years later, it's an immense gift that I don’t know how to repay.” The play was first performed at Repertorio Español on February 28, 1996 as part of its “New Voices” program, which aimed to foster the work of emerging Spanish-language writers in New York City. “I’ve said this before, but I don’t know how else to say it—a writer needs somebody to say yes and they [Repertorio Español] said yes.”

La Gringa was initially conceived as a one-act play titled Universe, which was set in Puerto Rico and featured two characters, María and her uncle Manolo. Rivera wrote the play in 1990 while she and her husband and fellow playwright Cándido Tirado were members of the Shaman Repertory Theatre. “He was the one who encouraged me to develop the play into a full-length, which became La Gringa,” says Rivera.

The characters of María and Manolo, along with themes of cultural identity and affirmation, would be developed further into La Gringa, which tells the story of María Elena, a young woman who travels to Puerto Rico during the holidays for the first time to discover her roots and meet her extended family. There, she confronts the familiar tensions between Puerto Ricans living on the island and those who are born or raised elsewhere. Rivera initially wrote her play in English with only one character who spoke Spanish—a reflection of her own childhood. “There was code-switching [in the play] because that was my experience growing up with my grandmother. She didn't speak English to me; I didn't speak Spanish to her.”

Rivera worked with La Gringa director Rene Buch on a translation of the script. “I was completely intimidated to work with [René Buch]—he was also the artistic director of the company,” recalls Rivera. “But he was quite generous with me, we worked well together.” It was Buch, for example, who suggested the main character quickly move past their initial struggles with speaking Spanish, which could be conveyed in other ways. Rivera, in turn, insisted on María Elena’s difficulty with the subjunctive tense. Ultimately, Rivera says, “I think that experience gave me more courage for myself to be present with the Spanish that I do have, be present with myself being a diasporican—that's who I am, I can't be who I'm not. I'm from New York, and I'm from Puerto Rico.”

Even so, Rivera has endured from audiences the very tropes examined in the play since La Gringa first opened. “I had people come up to me and say, you know, ‘I really liked the show and I think you're a really good writer, pero para que sepas, tú no eres boricua.’ Like they made it a point to say ‘Just so you know, you're not really Puerto Rican.’”

Rivera credits Buch with influencing other dynamics within the play as well, including the set design:

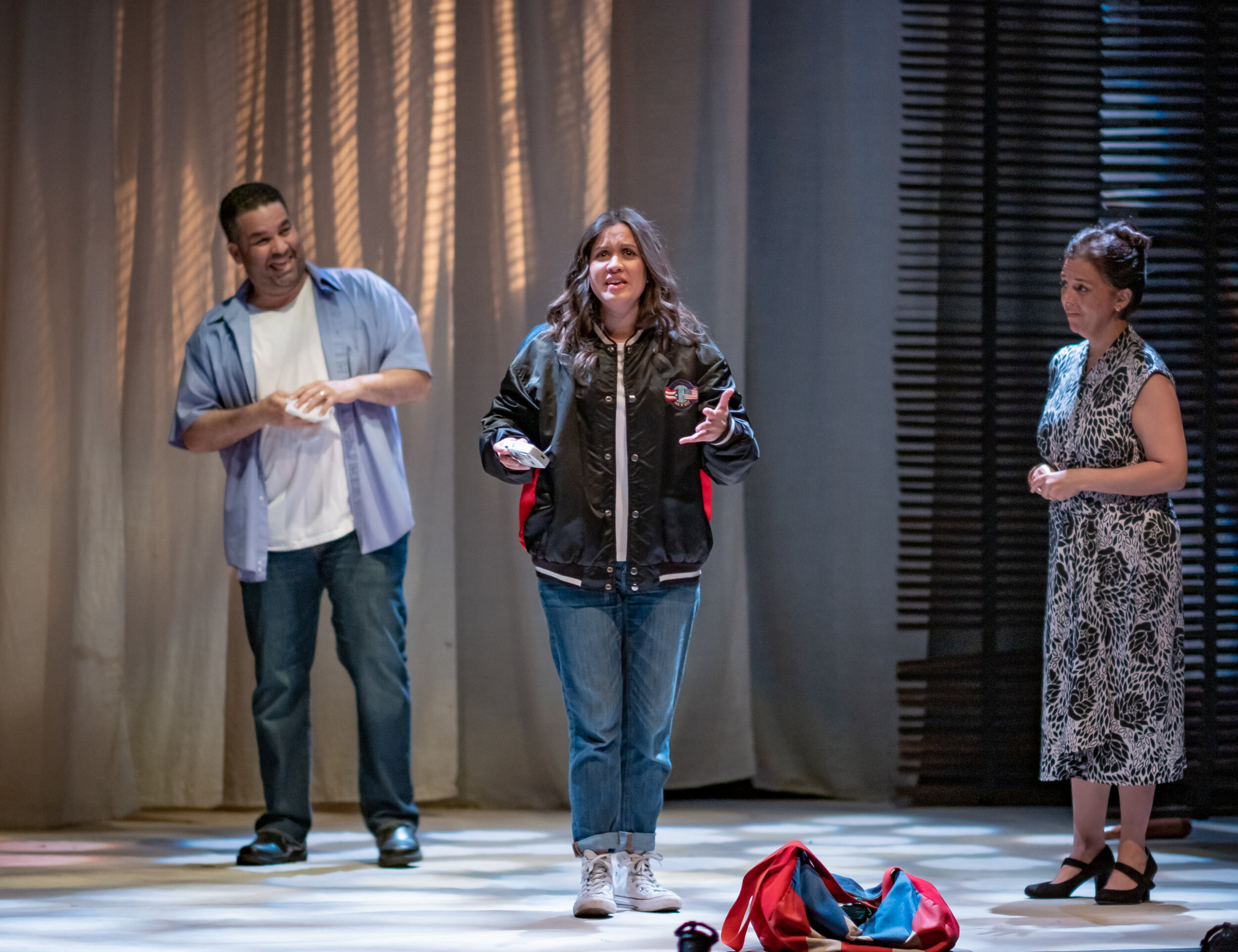

“The first thing he told me was that he wanted to reconfigure the set in a minimalist style. He worked with the designer to create a metaphoric set. They used wooden panels and white fabric, which would change colors with the lights and project images. This minimalist/metaphoric style really added a universal aspect to the play—where the search for Puerto Rican identity in La Gringa became a human search for self.”

Unfortunately, Buch, who was also a co-founder of Repertorio Español, passed away last year at the age of 94. “I wish he could be here for the celebration, I believe he was instrumental in the success of La Gringa,” says Rivera. “He did a wonderful job in directing my play.”

Following the success of La Gringa, which won an O.B.I.E. award, Rivera’s oeuvre expanded to include numerous works, several of which focus on larger-than-life cultural and historical figures such as La Lupe (La Lupe: My Life, My Destiny) and Julia de Burgos (Julia de Burgos: Child of Water), and Celia Cruz, co-written with Cándido, (Celia: The Life and Music of Celia Cruz); as well as Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo (La caída de Rafael Trujillo). Rivera also co-directs Educational Play Productions alongside her husband.

Her plays have also traveled outside of New York, across the United States, abroad, and to Puerto Rico, where La Gringa was performed. “We were nervous about doing the show in Puerto Rico,” recalled Rivera. The overall reception, however, was positive. “I think there's a recognition that there's a struggle being on the island and dealing with the situation there and then the person who is longing and having this connection and knowing that part of you is someplace else.”

The trip also led Rivera to revisit the script after a conversation with the cousin who inspired the character of Iris in the play. “For some reason, we were talking about place, and then I said, ‘I don't know why I feel so connected to Puerto Rico, I do. I just do, I just feel really connected here.’ And she goes, ‘aunque tú eres gringa, tú eres boricua también.’” Rivera added the line to the production that same night of the performance and later, to the print edition of La Gringa, which was published in English and Spanish editions by Concord Theatricals in 2009.

In-person plans to celebrate La Gringa’s 25th anniversary have been put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, though Repertorio Español has recently made a performance of the play available for online streaming. It is one of the many ways that theater venues have been forced to adapt to the negative impact of the pandemic on the arts and entertainment sector in New York City, which was outlined in a recently released report. In any case, Rivera offers a more hopeful perspective, noting how theater has survived and adapted not only tragedy, but the advent of everything from radio to Internet streaming. “People still want to do theater; people still want live interaction,” says Rivera.

El Repertorio Español, for example, has experimented with new technologies, including an innovative production last summer of a play written by Juan Ramirez entitled Calling Puerto Rico and directed by Cándido, who himself used the backdrop of the pandemic to pen The Magic Garden, a play about a man stuck at home during quarantine. “I think that we're just I think we're going to see so many different ways of art-making,” Rivera adds. Technology, she recalls, was instrumental in allowing her and a group of over 30 playwrights to collaborate on Aftermath, a full-length play which helped raise funds for Hurricane Maria disaster relief as part of #Pages4PuertoRico.

Writing during the pandemic, however, had not been a priority as Rivera focused on the shift to online learning. “I was teaching full time at The New School and I'm not good with technology. I had never set up a Zoom meeting,” says Rivera. It wasn’t until this past Christmas holiday that she realized she had not written anything for almost a year. “It felt good to write, like, ‘oh, okay, I'm still here.’”

Her plans now include writing a new play, as well as adapting one of her old plays into a television show. She is also interested in producing a film version of La Gringa, having written a screenplay with filmmaker Elisha Miranda. A feature film would certainly help Rivera’s signature play reach new audiences, but for now, its legacy remains firmly rooted to the stage, across generations. “I've heard that parents will bring their children because they saw it when they were younger,” Rivera says. “So I just feel very proud that it's at El Repertorio, that they've kept it, and that families can share the story.”

Visit Repertorio Español’s website to stream La Gringa.

To learn more about Carmen Rivera, visit her website: http://www.carmenrivera-writer.com/

Néstor David Pastor is a writer, editor, and translator from Queens, NY. He is the founding editor of Intervenxions, a Latinx arts and culture publication of the Latinx Project at NYU, and Huellas, a bilingual magazine featuring long-form writing by emerging Latin American and Latine writers. His past editorial work includes the award-winning NACLA Report on the Americas, a print magazine by the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), and CENTRO Voices, a digital publication of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College. He is the editor of Latinx Politics–Resistance, Disruption, and Power (2020), Intervenxions Vol. 1 (2022) and Intervenxions Vol. 2 (2023). In 2022, he was the recipient of the Queens Arts Fund ‘New Work’ grant. Most recently, he was selected to participate in the 2023 NALAC Leadership Institute. An essay on Cayman Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art is forthcoming in Nuyorican Art: A Critical Anthology (Duke University Press, 2024). To see his full portfolio and current projects, visit: www.ndpastor.com