Armando Alleyne: A Few of My Favorites [REVIEW]

Unlike most monographs, Armando Alleyne: A Few of My Favorites was not developed on the occasion of an exhibition or other milestone. The weighty, softcover volume contains 244 pages of poems, photos, and ephemera, alongside plates of Alleyne’s paintings that delineate an overlooked devotion to queer community and artistic practice. Armando Alleyne (b.1959, NYC) endured tremendous loss and trauma on two fronts: as a Black Latino in a nation founded on white supremacy, and a witness to the loss of an entire generation during the AIDS epidemic. A Few of My Favorites is an education, and no mournful (or luscious) detail is skimped on.

The first painting in the book, The Shelter Blues (2002), depicts a lone figure in bed (possibly the artist himself) surrounded by vibrantly colored rectangles with a clock looming overhead. This is our introduction to Armando's relationship with homelessness, and resilience in the face of constant emotional and physical displacement. Beside the image, he gives thanks to Olodumare—‘the supreme being.’ This is the first of many references to Yoruba-derived religious practice, a gift imparted by way of his Puerto Rican mother and Barbadian father. Raised in Lower Manhattan with his nine siblings, Alleyne’s parents also instilled a love for arts through visits to MoMA, Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and the West Village (a cultural hub of its own in the 60s). His father knew Thelonious Monk, who Armando would later paint—along with Jazz icons Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Josephine Baker, Johnny Pacheco. Even Biggie Smalls makes an appearance in later works.

On the interior sleeve is Diallo (Blind Justice), a poem written in response to the aftermath of Amadou Diallo’s murder in 1999, and the acquittal of four NYPD officers. Alleyne’s work, although remarkably underrecognized, is tragically relevant––this poem could have been written this week. As a nation, we’ve just witnessed the Kyle Rittenhouse & Ahmaud Arbery cases unfold. In The Shooting of Amadou Diallo (1999), Alleyne paints the same NYPD officers with amorphous faces, animalistic snouts, and seething teeth. Their guns are talon-like extensions of their hands. His narrative and compositional skill err on the poetic, even retablo-like, in his ability to deliver spirituality and magic realism at once. Billie Holiday-Stormy Weather (Orange Background) (2002) is one such standout. We see severed heads at the base of the partially ablaze Twin Towers. Billie is kneeling and at a distance, an nkisi nkondi is painted like the American flag, covered in tacks. The power figure holds a lightning bolt and is emerging from a turbulent sky. I wonder if the vengeful rhetoric post 9/11 prompted this figure into existence.

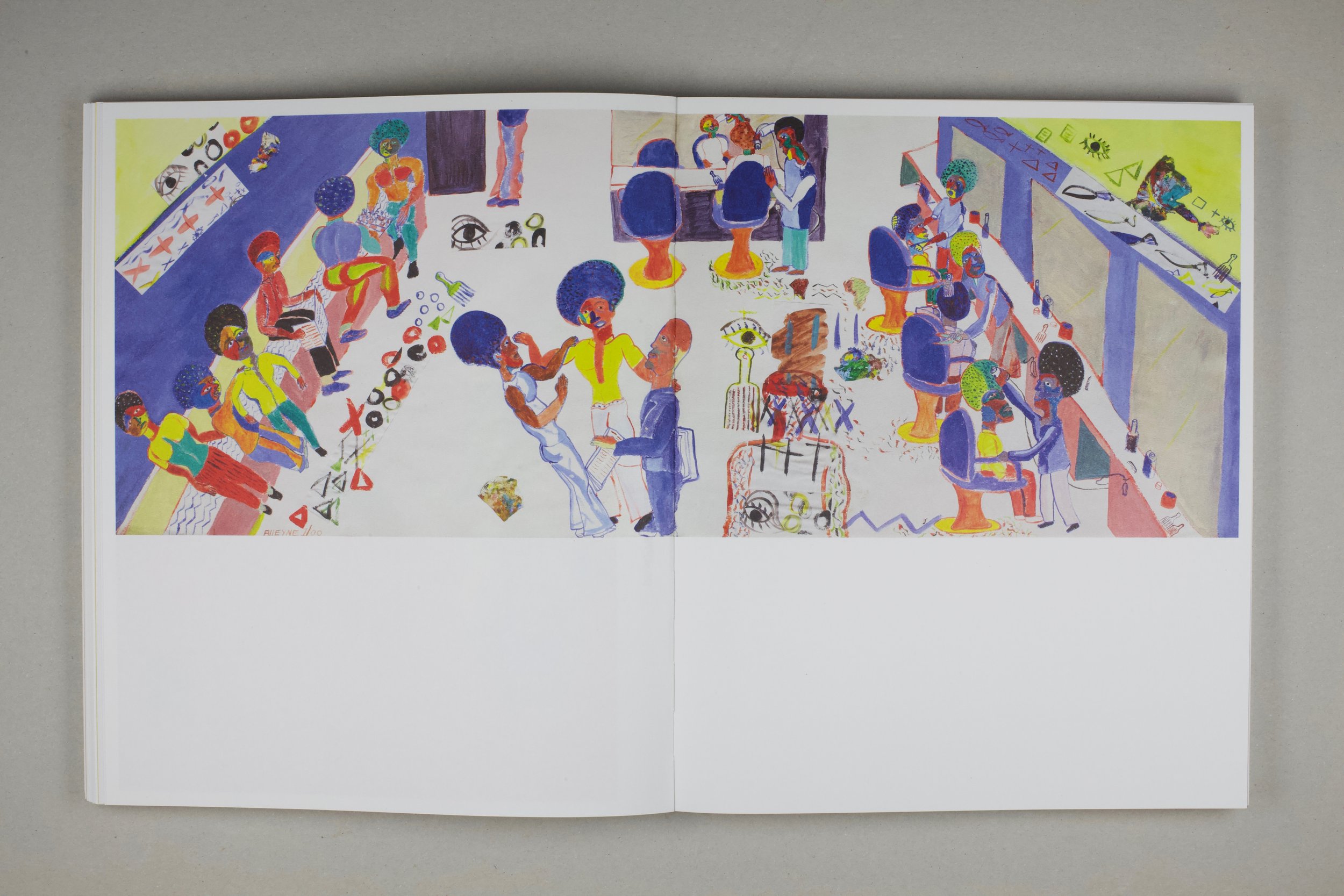

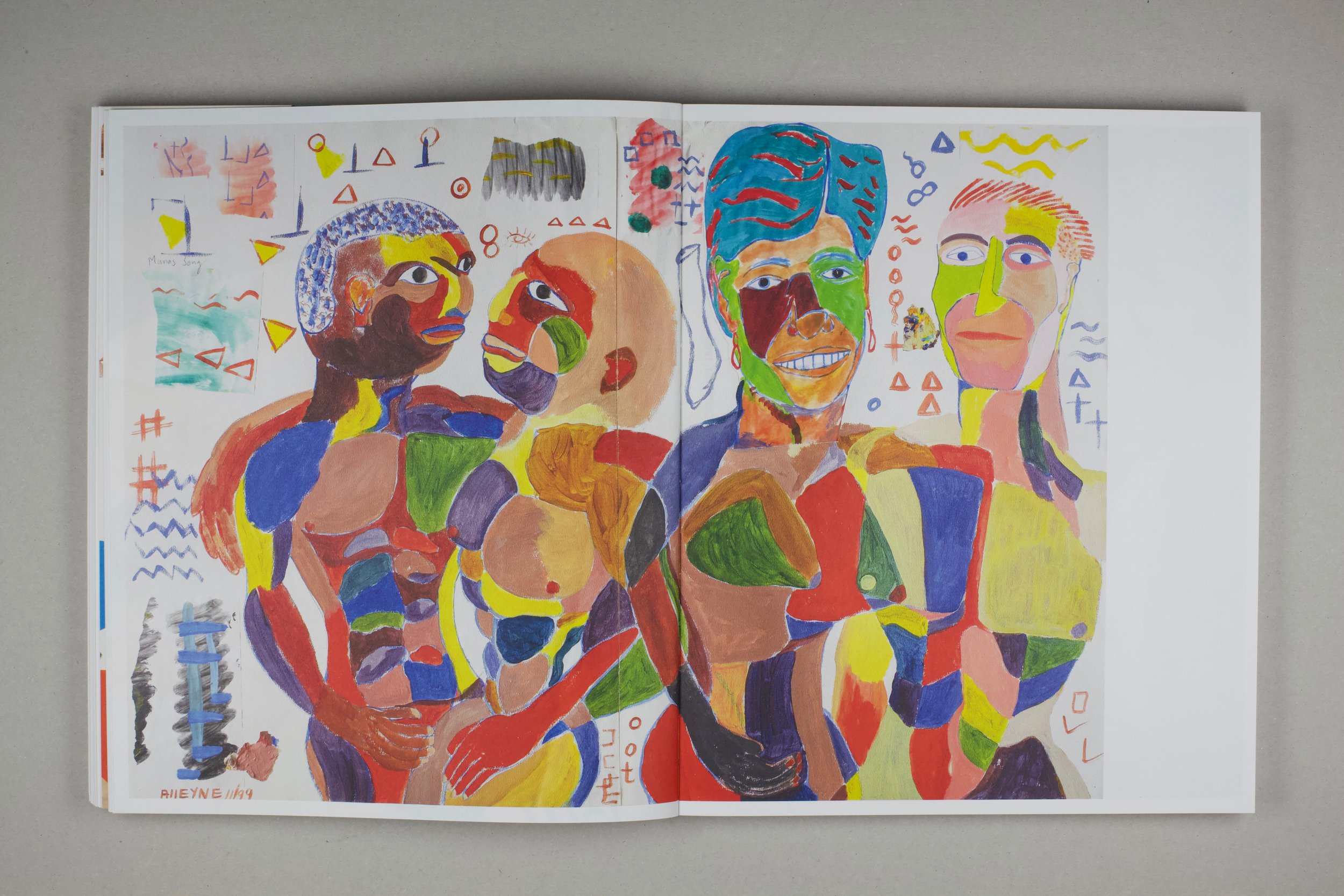

There is no sorrow without joy. The works shift from soft abstractions in pastel to figurative collages incorporating clippings from newspapers/magazines and intimate ballpoint sketches of figures dancing on a white page. His portraits of friends and family in communion radiate in fractured saturated colors that create a material parallel to his own diasporic identity. Executed in crayon, colored pencil, and acrylic paint, depictions of men in the buff dancing and holding each other in nature are likened to “Adam & Adam”. They’re looking into each other's eyes, and somehow into those of the viewer. In the ‘80s while at City College, Alleyne would hire nude models to reinvent poses from GQ. The resulting compositions were graciously gay, and included sex paraphernalia. In Dreaming (1998), two men lay side by side at the beach, dunes and sky at a distance, one gentleman has his arm outstretched, discreetly holding the other’s member against the sand. A musky peach glow in soft pastel envelopes the two, and I can’t help but feel this is my own memory, my own heartache. It is hard not to be swooned by images that teeter between love and passion.

I clapped alone and audibly more than once for Other Means, the graphic design studio based in Brooklyn and behind the scenes of this project. There is gentleness and poetry in how these heavy-hitting images are presented without chronology. Instead, we are confronted with the immensity of Alleyne’s archive, and the privilege of having these materials excavated and at our fingertips. How have they never graced the walls of the Leslie Lohman Museum, El Museo Del Barrio, or Whitney Museum of American Art? Perhaps this book will light a fire under the right institution’s collections team.

It isn’t till halfway through the book that plates are contextualized with anecdotes by Alleyne.

In a black and white portrait, he is seen resting on a windowsill in jeans and Adidas, leg perched, drinking a cup of coffee while looking into the lens. The sun is beaming on him in chiaroscuro fashion. Beside the photo he describes the heat of that day, and a friend (Michael A. Cummings), who would become a lifelong supporter. Maria’s Song poems accompany a painting of the same title, in honor of Armando’s sister who passed from AIDS. Maria was a Leo full of duality, he describes—making careful mention of the influences behind her portrait, from Éduoard Manet’s Olympia to Betye Saar’s use of color. Above Maria is an angel, gently grazing her leg, hieroglyphs placed rhythmically on her exposed skin in place of lesions. I’m instantly reminded of the book's opening painting The Shelter Blues (2002), which was painted just a year later.

At the close is, “Remember This, No One Found You, You Were Always Here,” an essay by Tiona Nekkia McClodden, who is a visual artist, filmmaker, and curator invested in Queer sociocultural commentary. She recently curated the standout Barbara Hammer show, Tell me there is a lesbian forever…, at Company Gallery. Tiona has a knack for paying homage while establishing a sincere bond. The text reads as a numbered account of her relationship with Alleyne, from her invitation to write an essay for the book, to the very real triggers/empathy raised by his imagery, and their first in-person meeting. The title is pointed; Tiona makes note of her experience with Black spirituality and cultural practice in the South—particularly how white-wall spaces co-opt the work of Black artists by using “outsider art” and other quasi-diminutive language as descriptors. It could be read as a cautionary tale for the esteem of a newly appreciated artist.

Edition Patrick Frey, the Swiss publishers who pride themselves on first monographs with emerging and under-recognized artists, have produced a breakthrough. Editors Stephanie Rebonati and Laura Serejo Genes managed to compile over 40 years of artwork, illustrating that Alleyne is simultaneously a master and just getting started. Pre-order yourself a copy, and remember that queer art, accessibility, and pedagogy don’t trickle from the gallery down.

Armando Alleyne: A Few of My Favorites is available for pre-order here. For additional book images, click here.

Armando Alleyne: A Few of My Favorites

Softcover, 244 pages, 29.2 × 24.1 cm. Edition Patrick Frey, No. 325, $60

Nicole Mouriño is a Brooklyn-based Artist & Arts Administrator. She holds an MFA in Social Practice from Queens College & BFA in Painting from Pratt Institute of Art. Mouriño has developed exhibitions/projects with various institutions including The Whitney Museum of American Art, Kunsthall Stavanger, The Drawing Center, & The Feminist Institute. She has supported the development of major publications with Mousse Publishing, The Drawing Papers, & Edition Patrick Frey. Recently she was an A.I.R. at The National YoungArts Foundation, & recipient of the IconBay Sculpture Park Award. Mouriño is the Head of Arts Programs of The Latinx Project at NYU.

Armando Alleyne (b. 1959, New York) grew up in Lower Manhattan and graduated from The City College of New York with a B.A. in Education and Fine Arts, in 1983. Throughout the decades, Alleyne's work has been shown at Sage Center Harlem, Gallery M, Chi Chiz, the Bronx River Gallery, Clover's Fine Art Gallery, Metropolitan Community Church, Sarah Lawrence College, the Jazz Gallery and Black Lawyers Association, among others. He has illustrated numerous publications including Blackheart 2: The Prison Issue—A Journal of Writing and Graphics by Black Gay Men (1984), Black Music, Black Poetry: Blues and Jazz's Impact on African American Versification (Gordon E. Thompson, 2014), Kwanzaa in the Gay and Lesbian Family (Imani Rashid, 2011) and Saving the World from Self–Or Should I Say Selfishness (Philip Regman, 2010). He lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.