Archiving NYC’s Diverse Diasporic Communities

For racial justice advocate and archivist Djali Alessandra Brown-Cepeda, Instagram has served as a tool to document and preserve New York City’s Latinx culture and history and, more recently, “Black in the day history,” as she describes it.

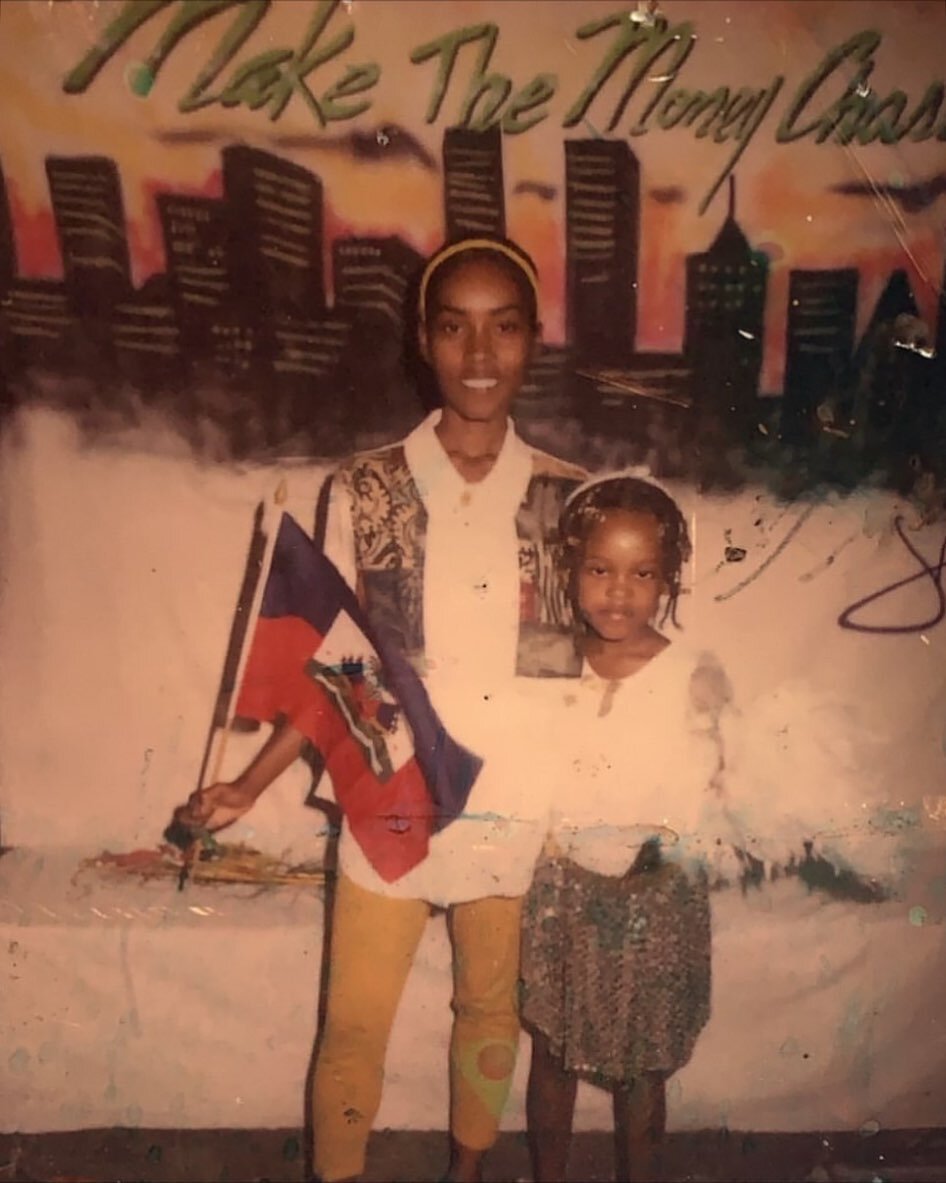

Though her journey to archival work began at a very young age, Brown-Cepeda’s now 2-year-old platform, Nuevayorkinos, turned her passion project into a digital photo album for NYC-centered Latinx family photos and stories. Scrolling through Nuevayorkinos’ page, you’ll not only see a combination of images—family photos en la sala, holiday stills and shots in front of quintessential NYC Latinx hotspots like Orchard Beach in the Bronx or neighborhoods like El Barrio, or East Harlem, to name a few—but experience a bevy of emotions, including pride, joy and even a tinge of sadness. The feelings the 30K follower page evokes are a testament to the community that powers it. Brown-Cepeda keeps things organic, allowing Nuevayorkinos' audience to dictate how the images will be showcased and the flow of the accompanied stories. Led by user submissions, she publishes photos on a rolling basis, keeping in mind the cadence in which she’s representing specific nationalities and NYC locales. It’s extremely important for the artivist to show the diverse experiences of Latinxs across the five boroughs, making their stories accessible to all who want to engage with Nuevayorkinos. She even offers the accompanying caption in English, Spanish and Portuguese.

“It's very important for me to make sure that I am paying homage to the gente,” says Brown-Cepeda, a Black-American and Dominican-American creative. “People have sent me photos that were, in terms of their quality, very crisp. Other people have sent me very pixelated photos. It's what you have access to. So, I've always wanted to make it accessible. Social media—Instagram, in my case being my main sort of interface—is something that most people do have access to. Digital spaces can also be incredibly inaccessible. So for me, it's so much more important to just get the stories out there than tailor them, try to refine them, polish them, because also like, who am I to do that?”

As she navigates this archival, artivist oral history project, Brown-Cepeda is also reimagining and questioning the archive and what these modalities of remembrance look like, and what they can and can't be. It’s why she chooses not to censor the submissions, resulting in authentic storytelling.

“I’m prioritizing the community, prioritizing the people, because they are the lifeline of this project,” she adds. “If they didn't exist, if we as a community didn't exist, then this project wouldn't exist.”

With the growth of Nuevayorkinos, Brown-Cepeda is equally as passionate about bringing the community with her as new doors open. She’s had the opportunity to bring Nuevayorkinos’ digital presence to in-person activations at El Museo del Barrio for #MIBARRIO: Memories of Home, Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA), the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI), and BreadxButta.

While spaces like the CCCADI, MACLA and BreadxButta allowed for a seamless showing of Nuevayorkinos, she had a telling experience with El Museo. As Brown-Cepeda was installing the exhibition, chief curator Rodrigo Moura and a colleague came in without uttering a word to her. Though she could’ve ignored their actions, she took it as an opportunity to introduce herself and focus on the community-centered work happening within the museum. She zeroed in on her personal mission with the exhibition: To bring people from public housing to former tenement buildings back to a space that was created with them in mind.

“I did have to confront that very real sort of like white male gaze,” she says. “That's throughout the art world in general, in the museum world in general, and the curatorial world in general.”

The incident is a reminder to Brown-Cepeda as to why she started her archival journey. After watching a series that centered colonial narratives during a February 2019 visit to the Dominican Republic, she began scrolling through Instagram where she came across several archival accounts like Sunu Journal (started by her former professor, Amy Sall) dedicated to Pan-African storytelling and Guadalupe Rosales’ Veteranas and Rucas, which centers Chicanx culture in Southern California. An admirer of both spaces, the Caribbean-American artivist couldn’t see her full self within the experiences shown; and ventured to create a space that would. Nuevayorkinos was born. She immediately went on GoDaddy to purchase the domain and secured the Instagram account.

Brown-Cepeda tapped her friends, who are also native New Yorkers, and her own mother, Raquel Cepeda, to submit to Nuevayorkinos. In the page’s first post, a teenage Cepeda can be seen sitting on her best friend’s steps on Broadway and 213th Street in Inwood. As a curator, Brown-Cepeda found herself straddling the thin line between sharing her maternal family with her growing audience and respecting their privacy. With her mother’s well-known book, Bird of Paradise: How I Became Latina, providing intimate details of her family’s life, Brown-Cepeda created Nuevayorkinos’ sister site, BLK Then. It also quelled her yearning to represent her paternal lineage.

“In doing Nuevayorkinos, over the course of these years, I had felt I was being very exclusive to my dad’s family, by proxy to 50% of my whole identity. That wasn’t conducive with where I wanted to move forward with Nuevayorkinos and with my archival, artistic endeavours moving forward.”

It’s been two months since the founding of BLK Then, which documents the Black diasporic experience in New York City, and it’s gaining traction. You might even see overlap between BLK Then and Nuevayorkinos as the Black Latin American experience can be included in both spaces. Like Nuevayorkinos, the first post featured on BLK Then is a black-and-white photo of her father, Djinji Brown.

If the COVID-19 pandemic was not a reality, Brown-Cepeda planned to throw a two-year anniversary for Nuevayorkinos and a gathering in honor of Black History Month; however, she has plans to resume in-person festivities when it’s safe to do so. In fact, throughout the duration of the pandemic Nuevayorkinos was still able to host community initiatives such as the Back to School Drive in September and the Power to the People! Drive, providing much-needed support to families in Bushwick and Bed-Stuy. Brown-Cepeda has plans to bring these efforts to other NYC neighborhoods in the future.

She also has no plans of slowing down the expansion of Nuevayorkinos and BLK Then, and grateful to all who allow her to share their lived experiences digitally.

“I open the door for people to, if they choose to, be vulnerable to share their stories,” says Brown-Cepeda. “It just makes me so happy that even though I don't know these thirty thousand people, that I have been able to create the space where they feel comfortable and that people understand, or they feel my vibe through the page. It just feels so lovely to have been able to and to still be in the midst of creating community.”

Djali Alessandra Brown-Cepeda (she/her/hers) is a filmmaker, racial justice advocate, and archivist. A second-generation Dominican-American native New Yorker hailing from Inwood, Manhattan and the Soundview section of The Bronx, Djali is the founder and curator of Nuevayorkinos (est. February 2019) and BLK THEN (est. December 2020), digital archives dedicated to documenting and preserving New York City Latinx and Black culture and history through family photographs and stories, respectively. In 2019, Djali held Nuevayorkinos exhibitions at El Museo del Barrio (Harlem, NY) and the MACLA (San José, CA), landing her to be featured in publications, including Dazed Digital, The New York Times, and Remezcla. Djali has also been invited to speak at various institutions, including Barnard College, Columbia University, the Caribbean Cultural Center/African Diaspora Institute, and Harvard University. Graduating from Eugene Lang College at the New School University with a B.A. in Film and minor in Ethnicity & Race, Djali is a film producer who views filmmaking as a means of decolonization. She associate produced the Cannes award-winning branded short film, Railroad Ties (2019) and La Madrina: The Savage Life of Lorine Padilla (2020), an official selection in both the 2020 Tribeca and DOC NYC Film Festivals. La Madrina was the recipient of the 2020 DOC NYC Audience Award. Djali is currently working on several projects and is on the journey toward obtaining her Masters in Criminal Justice, with a dual concentration in Criminal Law and Policing. She currently resides in her native New York.

Janel Martinez is a multimedia journalist & the founder of award-winning blog, Ain't I Latina?, an online destination celebrating Afro-Latinx womanhood. The Bronx, NY native holds a BA in Magazine Journalism & Sociology from Syracuse University. Her writing has appeared in Adweek, BuzzFeed, ESSENCE, Oprah Magazine, & Remezcla, among other publications. She is a frequent public speaker discussing media, culture & identity, as well as diversity at conferences & events for Bloomberg, NBCU, SXSW, Harvard University & more. Her work will be included in the forthcoming anthology, Wild Tongues Can't Be Tamed, which will be published in fall 2021 by Flatiron Books.